Download Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

“Casey” Stengel Baseball Player and Manager 1890-1975

Missouri Valley Special Collections: Biography Charles Dillon “Casey” Stengel Baseball Player and Manager 1890-1975 by David Conrads In a career that spanned six decades, Casey Stengel made his mark on baseball as a player, coach, manager, and all-around showman. Arguably the greatest manager in the history of the game, he set many records during his legendary stint with the New York Yankees in the 1950s. He is perhaps equally famous for his colorful personality, offbeat antics, and his homespun anecdotes, delivered in a personal language dubbed “Stengelese,” which was characterized by humor, practicality, and long-windedness. Charles Dillon Stengel was born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri. He attended Woodland Grade School then switched to the Garfield Grammar School. A tough kid, with a powerful build, he was a great natural athlete and star of the Central High School sports teams. While still in school, he played for semi-professional baseball teams sponsored by the Armour Packing Company and the Parisian Cloak Company, as well as for the Kansas City Red Sox, a traveling semi-pro team. He quit high school in 1910, just short of graduating, to play baseball professionally with the Kansas City Blues, a minor-league team. Stengel made his major league debut in 1912 as an outfielder with the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was then that he acquired his nickname, which was inspired primarily by his hometown as well as by the popularity at the time of the poem “Casey at the Bat.” A decent, if not outstanding player, Stengel played for 14 years with five National League teams. -

Chapter 2 (.Pdf)

Players' League-Chapter 2 7/19/2001 12:12 PM "A Structure To Last Forever":The Players' League And The Brotherhood War of 1890" © 1995,1998, 2001 Ethan Lewis.. All Rights Reserved. Chapter 1 | Chapter 2 | Chapter 3 | Chapter 4 | Chapter 5 | Chapter 6 | Chapter 7 "If They Could Only Get Over The Idea That They Owned Us"12 A look at sports pages during the past year reveals that the seemingly endless argument between the owners of major league baseball teams and their players is once more taking attention away from the game on the field. At the heart of the trouble between players and management is the fact that baseball, by fiat of antitrust exemption, is a http://www.empire.net/~lewisec/Players_League_web2.html Page 1 of 7 Players' League-Chapter 2 7/19/2001 12:12 PM monopolistic, monopsonistic cartel, whose leaders want to operate in the style of Gilded Age magnates.13 This desire is easily understood, when one considers that the business of major league baseball assumed its current structure in the 1880's--the heart of the robber baron era. Professional baseball as we know it today began with the formation of the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs in 1876. The National League (NL) was a departure from the professional organization which had existed previously: the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players. The main difference between the leagues can be discerned by their full titles; where the National Association considered itself to be by and for the players, the NL was a league of ball club owners, to whom the players were only employees. -

Weaver on Strategy the Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team by Earl Weaver

Weaver on Strategy The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team by Earl Weaver Ebook available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Unlimited ebooks*. Accessible on all your screens. Book Weaver on Strategy The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team available for review only, if you need complete ebook "Weaver on Strategy The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team" please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >>> *Please Note: We cannot guarantee that every book is in the library. You can choose FREE Trial service and download "Weaver on Strategy The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team" ebook for free. Book Details: Review: Earl Weaver was manager of the Baltimore Orioles during most of their glory years, 1968- 1982 and 1985-1986 (skipping the World Series year of 1983). The team only had one losing record during that season and had stars like Jim Palmer, Eddie Murray, a young Cal Ripken, Lee May, and Mike Cuellar. The book is Weavers fairly straight forward view on... Original title: Weaver on Strategy: The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team Paperback: 202 pages Publisher: Potomac Books; Revised edition (May 1, 2002) Language: English ISBN-10: 1574884247 ISBN-13: 978-1574884241 Product Dimensions:6 x 0.5 x 9 inches File Format: pdf File Size: 15377 kB Ebook File Tags: earl weaver pdf,baseball fan pdf,baltimore orioles pdf,must read pdf,great book pdf,great read pdf,baseball strategy pdf,baseball book pdf,manager pdf,players pdf,advice pdf,rules pdf,team pdf,today pdf,greatest pdf,managed pdf,managers pdf,managing pdf,valuable pdf,coaches Description: During his career as the manager of the Baltimore Orioles, Earl Weaver was called “baseball’s resident genius.” His distinctive style of managing helped his teams finish first or second thirteen times in his seventeen years as a manager. -

April May June July August Sep Tember

2012 Schedule and Car Magnet Matt Wieters Orange Replica Jersey 6 (All fans) 13 (1st 15,000 fans 15 & over) T-Shirt Thursday Jim Palmer Replica Sculpture 26 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) 14 (All fans) Frank Robinson Replica Sculpture Orioles Cartoon Bird Home Cap APRIL 28 (All fans) 15 (1st 15,000 fans 15 & over) Little League Day #1 T-Shirt Thursday 29 (Pre-registered little leaguers) JULY 26 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) Day Camper Day (Pre-registered day campers) T-Shirt Thursday 10 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) Orioles Maryland Flag Floppy Hat presented by 27 Miller Lite (1st 20,000 fans 21 & over) Brooks Robinson Replica Sculpture Fireworks (post-game) 12 (All fans) (All fans) Mother’s Day Sun Hat 13 (1st 10,000 females 18 & over) T-Shirt Thursday Field Trip Day presented by MASN & WJZ-TV 9 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) 23 (Pre-registered school groups) MAY Eddie Murray Replica Sculpture Fireworks (post-game) 11 (All fans) 25 (All fans) Kids Run the Bases (post-game) Orioles Camouflage Script T-shirt 12 (All kids 14 & under) 27 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) AUGUST Orioles Collectible Truck presented by W.B. Mason Little League Day #2 15 (1st 10,000 kids 14 & under) (Pre-registered little leaguers) Fireworks (post-game) 24 (All fans) Drawstring Bag presented by MLB Network 13 (1st 10,000 fans) Cal Ripken Replica Sculpture Oriole Park 20th Anniversary Tumbler 6 (All fans) 23 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) T-Shirt Thursday Kids Run the Bases (post-game) 13 (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) 24 (All kids 14 & under) 28-30 Fan Appreciation Weekend JUNE T-Shirt Thursday (1st 10,000 fans 15 & over) 28 Fireworks (post-game) SEPTEMBER 28 (All fans) Fireworks (post-game) (All fans) 29 Fans’ Choice Bobblehead presented by AT&T 29 (1st 20,000 fans 15 & over) Earl Weaver Replica Sculpture 30 (All fans) July 15 July 13 TH ANN 20 IV ER S A R Y July 27 1 9 92 2012. -

Want and Bait 11 27 2020.Xlsx

Year Maker Set # Var Beckett Name Upgrade High 1967 Topps Base/Regular 128 a $ 50.00 Ed Spiezio (most of "SPIE" missing at top) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 149 a $ 20.00 Joe Moeller (white streak btwn "M" & cap) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 252 a $ 40.00 Bob Bolin (white streak btwn Bob & Bolin) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 374 a $ 20.00 Mel Queen ERR (underscore after totals is missing) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 402 a $ 20.00 Jackson/Wilson ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 427 a $ 20.00 Ruben Gomez ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 447 a $ 4.00 Bo Belinsky ERR (incomplete stat line) 1968 Topps Base/Regular 400 b $ 800 Mike McCormick White Team Name 1969 Topps Base/Regular 47 c $ 25.00 Paul Popovich ("C" on helmet) 1969 Topps Base/Regular 440 b $ 100 Willie McCovey White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 447 b $ 25.00 Ralph Houk MG White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 451 b $ 25.00 Rich Rollins White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 511 b $ 25.00 Diego Segui White Letters 1971 Topps Base/Regular 265 c $ 2.00 Jim Northrup (DARK black blob near right hand) 1971 Topps Base/Regular 619 c $ 6.00 Checklist 6 644-752 (cprt on back, wave on brim) 1973 Topps Base/Regular 338 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 1973 Topps Base/Regular 588 $ 20.00 Checklist 529-660 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 263 $ 3.00 Checklist 133-264 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 273 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 upgrd exmt+ 1956 Topps Pins 1 $ 500 Chuck Diering SP 1956 Topps Pins 2 $ 30.00 Willie Miranda 1956 Topps Pins 3 $ 30.00 Hal Smith 1956 Topps Pins 4 $ -

Dud Branom, “Millionaire First Baseman” ©Diamondsinthedusk.Com

Dud Branom, “Millionaire First Baseman” ©DiamondsintheDusk.com On April 12, 1927, the New York Yankees beat the Philadelphia Athletics 8-3 in the season opener for both teams. In a game that features 11 future Hall of Famers, Dud Branom Debut it’s a little known 29-year-old rookie first baseman making his major league debut April 12, 1927 with the Athletics who is the wealthiest player on the field. A native of Hartshorne, Oklahoma, Edgar Dudley (Dud) Branom is already indepen- dently wealthy as his father-in-law is one of the Sooner State’s richest oil barons. Five years earlier, at the ripe old age of 24, Branom buys the Enid Harvesters of the Western (C) Association club prior to the start of the 1922 season. In addition to his financial interest in the Harvesters, Branom is also the team president, business manager as well as the on-the-field captain. On February 18, 1922, The Sporting News reports that, “Dud Branom has finally secured possession of the Enid franchise, the deal being completed when Branom, who was the property of the Kansas City Blues, secured his release on condition that he become financially interested in the Enid club. He will act as field captain and business manager, playing his old position of first base.” Under Branom’s ownership, the Harvesters prove to be an artistic, if not a financial, success finishing the season with a 104-27 mark and setting two minor league marks: fewest losses by a 100-win team and the highest winning percentage (.794). -

Home Plate: a Private Collection of Important Baseball Memorabilia

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE : 8 O C T O B E R 2020 HOME PLATE: A PRIVATE COLLECTION OF IMPORTANT BASEBALL MEMORABILIA AUCTION: DECEMBER 16 PREVIEW BY APPOINTMENT: DECEMBER 11-16 NEW YORK – Christie’s and Hunt Auctions announce a historic offering from a single owner private collection of baseball memorabilia and trading cards presented within a December 16 auction entitled “Home Plate: A Private Collection of Important Baseball Memorabilia.” The collection has been assembled over the last 25 years, and features iconic players, teams, and moments in the history of Major League Baseball with specific focus on items of scarcity. With over 150 lots in total, estimates range from $500-1,000,000. “This particular private collection has remained largely unknown within the industry for over 25 years.” stated David Hunt, President, Hunt Auctions. “We expect the debut of this world class collection to mark as one of the finest of its type to have been offered at public auction. A great number of the items within are being unveiled to the public for the very first time including several which are the finest known examples of their medium. Hunt Auctions is thrilled to partner with Christie’s to present this iconic offering of historic baseball artifacts.” The auction presents lots from across the history of baseball, with items autographed, owned, and used by icons such as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Christy Mathewson, Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner. The collection is notable for some of the greatest artifacts extant relating to the 1903 World Series, 1927 New York Yankees, and the 1934 U.S. -

View Key Chapters of Casey's Life

Proposal by Toni Mollett, [email protected]; (775) 323-6776 “There comes a time in every man’s life, and I’ve had plenty of them.” — Casey Stengel KEY CHAPTERS IN CASEY’S LIFE AT BAT, IN THE FIELD, THE DUGOUT, THE NATION’S HEART 1910-12: Born in 1890 in Kansas City, Missouri, Charles Dillon Stengel, nicknamed “Dutch,” excels in sports. His father is a successful insurance salesman and his son has a happy childhood, playing sandlot baseball and leading Central High School’s baseball team to the state championship. To save money for dental school, Stengel plays minor-league baseball in 1910 and 1911 as a left-handed throwing and batting outfielder, first with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. At 5-foot-11 and 175 pounds, he is fast if not physically overpowering. A popular baseball poem at the time is “Casey At the Bat,” that, plus the initials of his hometown, eventually garner him a new moniker. Casey finds his courses at Western Dental College in Kansas City problematic with the dearth of left-handed instruments. The Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers) show him a different career path, drafting him and sending him to the Montgomery, Alabama, a club in the Southern Association. He develops a reputation for eccentricity. In the outfield one game, he hides in a shallow hole covered by a lid, and suddenly pops out in time to catch a fly ball. A decent batter and talented base stealer, Casey is called up by Brooklyn late in the season. In his first game, he smacks four singles and steals two bases. -

Baseball's Transition to Professionalism

Baseball's Transition to Professionalism Aaron Feldman In baseball recently, much has been said about the problems with baseball as a business. Owners and players are clashing publicly on every imaginable issue while fans watch hopelessly. Paul White of Baseball Weekly observed, “Baseball… got beat up. Call it a sport, call it a business, call it an industry. Call it anything that can suffer a black eye,” in his analysis of the conflicts that have marked this off-season. i The fights might seem new to the casual observer, but they are not. To search for the origin of this conflict one must look back more than a hundred years, to the founding of the National Association of Professional Baseball Players in 1871. Indeed, the most permanent damage to professional baseball was during the period from 1870- 1885 when baseball evolved from an amateur game into a professional one. Though some of the blame belongs to the players of this era, the majority of the fault can be attributed to the owners. Owners, lacking no model to guide them by, made the mistake of modeling early franchises after successful industry. Baseball’s early magnates mishandled the sport’s transition from amateur to professional, causing problems with labor relations, gambling, and financial solvency. Before one can look at the problems faced by baseball in the period from 1870-1885, it is necessary to examine some of the trends that were involved in changing baseball’s shape dramatically. First of all was baseball’s unprecedented rise in popularity. One newspaper of the time called it, “that baseball frenzy” as fan enthusiasm multiplied.ii John Montgomery Ward wrote that, “Like everything else American it came with a rush. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

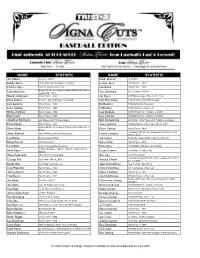

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Mediaguide.Pdf

American Legion Baseball would like to thank the following: 2017 ALWS schedule THURSDAY – AUGUST 10 Game 1 – 9:30am – Northeast vs. Great Lakes Game 2 – 1:00pm – Central Plains vs. Western Game 3 – 4:30pm – Mid-South vs. Northwest Game 4 – 8:00pm – Southeast vs. Mid-Atlantic Off day – none FRIDAY – AUGUST 11 Game 5 – 4:00pm – Great Lakes vs. Central Plains Game 6 – 7:30pm – Western vs. Northeastern Off day – Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, Mid-South, Northwest SATURDAY – AUGUST 12 Game 7 – 11:30am – Mid-Atlantic vs. Mid-South Game 8 – 3:30pm – Northwest vs. Southeast The American Legion Game 9 – Northeast vs. Central Plains Off day – Great Lakes, Western Code of Sportsmanship SUNDAY – AUGUST 13 Game 10 – Noon – Great Lakes vs. Western I will keep the rules Game 11 – 3:30pm – Mid-Atlantic vs. Northwest Keep faith with my teammates Game 12 – 7:30pm – Southeast vs. Mid-South Keep my temper Off day – Northeast, Central Plains Keep myself fit Keep a stout heart in defeat MONDAY – AUGUST 14 Game 13 – 3:00pm – STARS winner vs. STRIPES runner-up Keep my pride under in victory Game 14 – 7:00pm – STRIPLES winner vs. STARS runner-up Keep a sound soul, a clean mind And a healthy body. TUESDAY – AUGUST 14 – CHAMPIONSHIP TUESDAY Game 15 – 7:00pm – winner game 13 vs. winner game 14 ALWS matches Stars and Stripes On the cover Top left: Logan Vidrine pitches Texarkana AR into the finals The 2017 American Legion World Series will salute the Stars of the ALWS championship with a three-hit performance and Stripes when playing its 91st World Series (92nd year) against previously unbeaten Rockport IN.