1. the Role of Medicines in Achieving Universal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Shall Give You a Talisman. When Faced with a Dilemma As to What Your Next Step Should Be, Remember the Most Wretched and Vulnerable Human Being You Ever Saw

"I shall give you a talisman. When faced with a dilemma as to what your next step should be, remember the most wretched and vulnerable human being you ever saw. The step you contemplate should help him!" - Mahatma Gandhi About SEARCH Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health (SEARCH) is a voluntary organization working in rural and tribal regions of Gadchiroli district, Maharashtra. Gadchiroli district is situated on the eastern border of Maharashtra, bordering Chhattisgarh in the east and Andhra Pradesh in the south. The district headquarter, Gadchiroli, is about 175 km south of the nearest city Nagpur. Gadchiroli is one of the poorest and least developed districts in India. While rest of the Maharashtra and India is marching ahead, Gadchiroli district with nearly one million populations, 36% of which are tribal is lagging behind in various parameters of human develop- ment index. The problem is compounded by the emergence of Maoist movement. Inspired by the social philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, Drs. Abhay and Rani Bang founded SEARCH in 1986 after completing their public health training at Johns Hopkins University, USA. Our Vision and Mission Our programmes: SEARCH’s vision is 'Aarogya-Swaraj' or putting the ‘People’s SEARCH strives to achieve its objectives through following eight health in the people's hands.’ By empowering individuals and com- key programmes- munities to take charge of their own health, SEARCH aims to help Tribal-friendly hospital people achieve freedom from disease as well as dependence. Home-based -

Public Lecture: Dr. Abhay Bang on Aarogya Swaraj : in Search of Health Care for the People, Aug 19, 2014, Bangalore

Public Lecture: Dr. Abhay Bang on Aarogya Swaraj : In Search of Health Care for the People, Aug 19, 2014, Bangalore Event Sub Title: Aarogya Swaraj : In Search of Health Care for the People Speaker: Dr. Abhay Bang Director, SEARCH (Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health) Date / Time: August 19, 2014 - 6:00pm - 7:00pm Venue: Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan, #43, Race Course Road, Bangalore, Karnataka 560001 Enquiries / RSVP: [email protected] Seating will be on a first-come-first-serve basis. Kindly be seated 15 minutes prior to the start of the talk. The talk is free and open to all. A Note on the Speaker: Dr. Abhay Bang grew up in the Sevagram Ashram of Mahatma Gandhi. He was inspired by the social ideals, and trained in India (MD) and at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, (MPH). Along with his wife Dr. Rani Bang, he founded the voluntary organistion, SEARCH, (Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health) 25 years ago, in one of the most underdeveloped districts, Gadchiroli, Maharashtra where they have been working with the people in 150 villages to provide community-based health care and conduct research. They have developed a village health care program which has now become a nationally and internationally famous model. They first brought to the notice of the world that rural women had a large hidden burden of gynaecological diseases. He showed how pneumonia in children can be managed in villages, and recently, how new-born care can be delivered in villages. Their work has reduced the IMR to 30 in this area. -

पेटेंट कार्ाालर् Official Journal of the Patent Office

पेटᴂट कार्ाालर् शासकीर् जर्ाल OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE PATENT OFFICE नर्र्ामर् सं. 06/2020 शुक्रवार दिर्ांक: 07/02/2020 ISSUE NO. 06/2020 FRIDAY DATE: 07/02/2020 पेटᴂट कार्ाालर् का एक प्रकाशर् PUBLICATION OF THE PATENT OFFICE The Patent Office Journal No. 06/2020 Dated 07/02/2020 7261 INTRODUCTION In view of the recent amendment made in the Patents Act, 1970 by the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005 effective from 01st January 2005, the Official Journal of The Patent Office is required to be published under the Statute. This Journal is being published on weekly basis on every Friday covering the various proceedings on Patents as required according to the provision of Section 145 of the Patents Act 1970. All the enquiries on this Official Journal and other information as required by the public should be addressed to the Controller General of Patents, Designs & Trade Marks. Suggestions and comments are requested from all quarters so that the content can be enriched. ( Om Prakash Gupta ) CONTROLLER GENERAL OF PATENTS, DESIGNS & TRADE MARKS 7TH FEBRUARY, 2020 The Patent Office Journal No. 06/2020 Dated 07/02/2020 7262 CONTENTS SUBJECT PAGE NUMBER JURISDICTION : 7264 – 7265 SPECIAL NOTICE : 7266 - 7267 EARLY PUBLICATION (DELHI) : 7268 – 7293 EARLY PUBLICATION (MUMBAI) : 7294 – 7339 EARLY PUBLICATION (CHENNAI) : 7340 – 7416 EARLY PUBLICATION ( KOLKATA) : 7417 – 7429 PUBLICATION AFTER 18 MONTHS (DELHI) : 7430 – 7600 PUBLICATION AFTER 18 MONTHS (MUMBAI) : 7601 – 7773 PUBLICATION AFTER 18 MONTHS (CHENNAI) : 7774 – 8044 PUBLICATION AFTER 18 MONTHS (KOLKATA) -

Improving the Health of Mother and Child: Solutions from India

IMPROVING THE HEALTH OF MOTHER AND CHILD: SOLUTIONS FROM INDIA Priya Anant, Prabal Vikram Singh, Sofi Bergkvist, William A. Haseltine & Anita George 2012 PUBLICATION Acknowledgements We, ACCESS Health International, express our sincere gratitude to the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation for giving us an opportunity to develop a compendium of models in the field of Maternal and Child Health (MCH). Each of these models has contributed significantly towards developing innovative service delivery models and best practices in the area of MCH in India. In particular, we thank MacArthur Foundation Acting Director Dipa Nag Chowdhury and erstwhile Director Poonam Muttreja for their support, encouragement and time, which made this compendium possible. We appreciate the support and time provided by the leaders and team members of all the organisations that feature in this compendium and sincerely thank them for their support. We are grateful to the Centre for Emerging Market Solutions, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad for supporting us in bringing out this compendium. We thank Minu Markose for transcribing the interviews and Debjani Banerjee, Sreejata Guha, Kutti Krishnan and Mudita Upadhaya for helping us with the first draft of the cases. For editorial support, we thank Debarshi Bhattacharya, Surit Das, Anand Krishna Tatambhotla and SAMA editorial and publishing services. Table of Contents Introduction 01 Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health (SEARCH) 07 Mamidipudi Venkatarangaiya Foundation (MVF) 22 Ekjut -

National Affairs

NATIONAL AFFAIRS Prithvi II Missile Successfully Testifi ed India on November 19, 2006 successfully test-fi red the nuclear-capsule airforce version of the surface-to- surface Prithvi II missile from a defence base in Orissa. It is designed for battlefi eld use agaisnt troops or armoured formations. India-China Relations China’s President Hu Jintao arrived in India on November 20, 2006 on a fourday visit that was aimed at consolidating trade and bilateral cooperation as well as ending years of mistrust between the two Asian giants. Hu, the fi rst Chinese head of state to visit India in more than a decade, was received at the airport in New Delhi by India’s Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Science and Technology Minister Kapil Sibal. The Chinese leader held talks with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in Delhi on a range of bilateral issues, including commercial and economic cooperation. The two also reviewed progress in resolving the protracted border dispute between the two countries. After the summit, India and China signed various pacts in areas such as trade, economics, health and education and added “more substance” to their strategic partnership in the context of the evolving global order. India and China signed as many as 13 bilateral agreements in the presence of visiting Chinese President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The fi rst three were signed by External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing. They are: (1) Protocol on the establishment of Consulates-General at Guangzhou and Kolkata. It provides for an Indian Consulate- General in Guangzhou with its consular district covering seven Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hainan, Yunnan, Sichuan and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 30001 SYED NOORJAHAN SHIFA MEDICAL& GENRAL Female 9922224403 / NOT RENEW SAMINA D/O

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 30001 SYED NOORJAHAN SHIFA MEDICAL& GENRAL Female 9922224403 / NOT RENEW SAMINA D/O. SYED STORE MARKAJ MASJID 9850022332 MAQBOOL COMPLEX, NEAR COURT AMBAJOGAI, 431517 BEED Maharashtra 30002 KAPASI AZEEZ 17/35, SAFAVI APTS, Male 9819297549 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 17/02/2020 KURBANHUSAIN CHURCH ROAD, MAROL ANDHERI (E), 400059 MUMBAI Maharashtra 30003 JADHAV GORAKSHNATH AT-POST-MALALGAON, TAL- Male NOT RENEW BABAN VAIJAPUR, 423701 AURANGABAD Maharashtra 30004 CHAUDHARI KALPANA C/O-POKALE P.T.H.NO.5/7,J- Female NOT RENEW BAPURAO 1N N-9 MADHUKAR SOC.OP. 7, DEEPSEVA MANDAP CIDCO CIDCO 431003 AURANGABAD MAHARASHTRA 30005 KHANAPURKAR SANDIP OLD AUSA RD, B/H LAL Male 02382 200303 / NOT RENEW GANGARAM BAHADUR SHASTRI SCHOOL, 9422185134 PLOT NO.46, KRUSHI NAGAR 413512 LATUR Maharashtra 30006 JAHAGIRDAR VISHAKHA 06,SAPTARSHI APT , Female NOT RENEW SAGAR MODKESHWAR CHOWK, INDRA NAGAR, 422009 NASIK Maharashtra 30007 TEJOMAYEE 104, ASHIRWAD- 1, OFF Female 9322593646 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 17/02/2020 PANAMAGIPALLI J.P.RD, B/H SANJEEV ENCLAVE, 7 BUNGLOWS, ANDHERI (W) 400061 MUMBAI Maharashtra 30008 SHITOLE BALAWANTRAO AT-POST-KASODA, TAL- Male 9423491126 / NOT RENEW CHIMANRAO ERANDOL, 7588192672 425110 JALGAON Maharashtra 30009 UDANI DARSHANA 101, MANGAL BHAVAN BLDG, Female 9821527429 [email protected] NOT RENEW HASMUKH SARVODAYA LANE. GHATKOPAR [W] 400086 MUMBAI Maharashtra 30010 BANNE NITIN SHIV KRISHNA, KHARE Male 0233346626 NOT RENEW VISHWANATH MALA, -

In Search of a Healthy Solution

The Times of India , Mumbai, Friday, June 17,2011 HOME REMEDY In Search Of A Healthy Solution Harshad Pandharipande | TNN eonatology or the care of the just-born is a highly specialised medical discipline practised by super specialist doctors in the midst of perfectly sterile wards and incubators. In fact, the World Health Organization’s guidelines were unambiguous: Neonatal diseases are so complicated and delicate that ill infants should be rushed to hospital. Dr Abhay and Rani Bang turned this notion on its head. They put neonatal care in the hands of trained village health workers amidst much hand-wringing over the dangers of doing this. The result was the plummeting of the infant mortality rate (IMR) in 39 villages of Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district, where the Bang model was implemented, from 121 in 1987 to 30 in 2003. At that time, Maharashtra’s official IMR figure was 60. The Bangs calls this reduction of dependence on hospitals Arogya Swaraj. After completing their masters in public health from Johns Hopkins University, the Bangs chose to work in Gadchiroli, one of the poorest rural areas of Maharashtra. They set up a non-profit organisation called Search (Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health) in 1985. “There was no way that hospitals or modern health care would be accessible to infants and mothers in those remote villages. So, we decided to bring healthcare to their doorstep.” The solution was to empower rural mid- wives and new mothers with scientific knowledge. Community health workers are meticulously trained and go through regular checks to ensure their actions are by the book. -

Transformative Development

TRANSFORMATIVE DEVELOPMENT EMPOWERING INDIA’S WOMEN & GIRLS AMERICAN INDIA FOUNDATION • ANNUAL REPORT 2014-15 A math class at Gagodhar High School in Gujarat taught by an AIF Learning and Migration Program (LAMP) facilitator. TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM OUR LEADERSHIP ...3 17... SHAPING THE NEXT GENERATION OUR IMPACT ...4 OF SOCIAL CHANGE LEADERS LIGHTING THE PATH FOR A 19... GIVING LIFE TO INDIA’S NEWBORNS BRIGHTER FUTURE ...7 20... YEAR IN REVIEW TRANSFORMING THE CLASSROOM THROUGH TECHNOLOGY ...9 24... OUTREACH AND ENGAGEMENT BUILDING THE NEXT GENERATION OF 30... PARTNERSHIPS AND IMPACT INDIA’S WORKFORCE ...11 38... FINANCIALS INTEGRATING THE DIFFERENTLY-ABLED INTO INDIA’S ECONOMY ...13 42... PEOPLE CREATING ENTREPRENEURS ...15 52... SUPPORTERS FROM THE BOTTOM-UP © American India Foundation 2015. American India Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization. The material and all information contained herein is solely owned by and re- mains the property of the American India Foundation. It is being provided to you solely for the purpose of disclosing the information provided herein, in accordance with applicable law. Any other use, including commercial reuse, mounting on other systems, or other forms of publication, republication or redistribution requires the express written consent of the American India Foundation. AIF Rickshaw Sangh beneficiaries, Shyam Kishore Mandal and Phool Kumari, with their children, Vikas and Babli, in Bihar. Cover Photo: AIF Learning and Migration Program (LAMP) students at the Jangi Government School in Gujarat. Back Cover: AIF’s Maternal and Newborn Survival Initiative (MANSI) clinic in Jharkhand. (All Photographs in this Annual Report ©Prashant Panjiar unless otherwise stated) - 1 - FROM OUR LEADERSHIP Dear Friends, When Asma first stared at the screen, her eyes lit up with curiosity and ex- The first impact evaluation of MANSI revealed demonstrable impact in re- citement. -

Unpaid Dividend Data As on 11.10.2014

CUMMINS INDIA LIMITED UNPAID DATA FOR THE YEAR 2014-15 INTERIM Proposed date Year of NAME OF THE SHARESHOLDERS ADDRESS OF THE SHAREHOLDERS STATE PIN FOLIO NO. Amount trf to IEPF Dividend A AMALRAJ 18 A ARULANANDHA NAGAR WARD 42 THANJAVUR TAMIL NADU 613007 CUMMIN30177416379489 20.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A CHANCHAL SURANA C/O H. ASHOK SURANA & CO. II FLOOR, KEERTHI PLAZA NAGARTHPET BANGALORE KARNATAKA 560002 CUMM000000000A020320 875.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A CHANDRASHEKAR NO 694 31ST CROSS 15TH MAIN SHREE ANANTHNAGAR ELECTRONIC CITY POST BANGALORE KARNATAKA 560100 CUMMIN30113526757339 2800.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A GURUSWAMY J-31 ANANAGAR CHENNAI TAMIL NADU 600102 CUMM000000000A005118 6000.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A K VENU GOPAL SHENOY C/O A.G.KRISHNA SHENOY P.B.NO.2548, BROAD WAY ERNAKULAM COCHIN KERALA 682031 CUMM000000000A019283 2625.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A N SWARNAMBA 1864 PIPELINE ROAD KUMAR SWAMY LAYOUT 2ND STAGE BANGALORE KARNATAKA 560078 CUMM1304140000980618 125.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A RAJAGOPAL 25, ROMAIN ROLLAND STREET PONDICHERRY PONDICHERRY 605001 CUMM000000000A021792 7000.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A SHANKAR FUTURE SOFTWARE 480/481 ANNASALAI NANDANAM CHENNAI TAMIL NADU 600035 CUMMIN30154917493917 70.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT A SRIDHAR PLOT NO 132,15 RAGHAVAN COLONY SECOND CROSS STREET ASHOK NAGAR CHENNAI TAMIL NADU 600083 CUMM1203840000144756 70.00 09-Nov-21 2014-15 INT 912 - 913, TULSIANI CHAMBERS 212, NARIMAN POINT FREE PRESS JOURNAL MARG MUMBAI, A TO Z BROKING SERVICES PVTLTD MAHARASHTRA MAHARASHTRA 400021 CUMMIN30154914695555 -

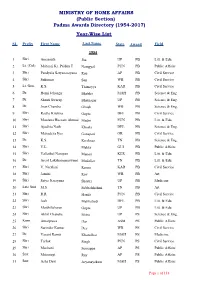

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt. -

April -2018 UPSC/IAS Current Affairs 1 9916399276

April -2018 UPSC/IAS Current Affairs www.iasjnana.com 1 9916399276 April -2018 UPSC/IAS Current Affairs „Central Vigilance Commission‟ Give directions to the Delhi Special Police (GS2: Statutory body) Establishment (CBI) for superintendence Issue: The Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) insofar as it relates to the investigation of has urged the Prime Minister‘s Office to bring offences under the Prevention of Corruption private sector banks under its watch, citing the fact Act, 1988 – section 8(1)(b); that they have been involved in many recent To inquire or cause an inquiry or investigation instances of malfeasance. to be made on a reference by the Central Current situation Government – section 8(1)(c); Vigilance officers in all State-owned public sector To inquire or cause an inquiry or investigation banks are required to report irregularities and to be made into any complaint received against possible wrongdoing to the CVC, India‘s apex any official belonging to such category of body for checking corruption in the government. officials specified in sub-section 2 of Section 8 Private sector banks are out of the CVC‘s of the CVC Act, 2003 – section 8(1)(d); purview, but are subjected to statutory audits from Review the progress of investigations the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). conducted by the DSPE into offences alleged to Empowering CVC will provide a strong deterrent have been committed under the Prevention of against those willing to engage in scams such as Corruption Act, 1988 or an offence under the Punjab National Bank scam Cr.PC – section (8)(1)(e); About CVC Review the progress of the applications pending The Central Vigilance Commission was set up by with the competent authorities for sanction of the Government in February,1964 on the prosecution under the Prevention of Corruption recommendations of the Committee on Act, 1988 – section 8(1)(f); Prevention of Corruption, headed by Shri K.