Waunarlwydd Canal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A TIME for May/June 2016

EDITOR'S LETTER EST. 1987 A TIME FOR May/June 2016 Publisher Sketty Publications Address exploration 16 Coed Saeson Crescent Sketty Swansea SA2 9DG Phone 01792 299612 49 General Enquiries [email protected] SWANSEA FESTIVAL OF TRANSPORT Advertising John Hughes Conveniently taking place on Father’s Day, Sun 19 June, the Swansea Festival [email protected] of Transport returns for its 23rd year. There’ll be around 500 exhibits in and around Swansea City Centre with motorcycles, vintage, modified and film cars, Editor Holly Hughes buses, trucks and tractors on display! [email protected] Listings Editor & Accounts JODIE PRENGER Susan Hughes BBC’s I’d Do Anything winner, Jodie Prenger, heads to Swansea to perform the role [email protected] of Emma in Tell Me on a Sunday. Kay Smythe chats with the bubbly Jodie to find [email protected] out what the audience can expect from the show and to get some insider info into Design Jodie’s life off stage. Waters Creative www.waters-creative.co.uk SCAMPER HOLIDAYS Print Stephens & George Print Group This is THE ultimate luxury glamping experience. Sleep under the stars in boutique accommodation located on Gower with to-die-for views. JULY/AUGUST 2016 EDITION With the option to stay in everything from tiki cabins to shepherd’s huts, and Listings: Thurs 19 May timber tents to static camper vans, it’ll be an unforgettable experience. View a Digital Edition www.visitswanseabay.com/downloads SPRING BANK HOLIDAY If you’re stuck for ideas of how to spend Spring Bank Holiday, Mon 30 May, then check out our round-up of fun events taking place across the city. -

Report of the Cabinet Member for Investment, Regeneration and Tourism

Report of the Cabinet Member for Investment, Regeneration and Tourism Cabinet – 18 March 2021 Black Lives Matter Response of Place Review Purpose: To provide an update on the outcomes of the Review previously commissioned as a result of the Black Lives Matter Motion to Council and seek endorsement for the subsequent recommendations. Policy Framework: Creative City Safeguarding people from harm; Street Naming and Numbering Guidance and Procedure. Consultation: Access to Services, Finance, Legal; Regeneration, Cultural Services, Highways; Recommendation: It is recommended that Cabinet:- 1) Notes the findings of the review and authorises the Head of Cultural Services, in consultation and collaboration with the relevant Cabinet Members, to: 1.1 Commission interpretation where the place name is identified as having links to exploitation or the slave trade, via QR or other information tools; 1.2 Direct the further research required of the working group in exploring information and references, including new material as it comes forward, as well as new proposals for inclusion gleaned through collaboration and consultation with the community and their representatives; 1.3 Endorse the positive action of an invitation for responses that reflect all our communities and individuals of all backgrounds and abilities, including black history, lgbtq+ , cultural and ethnic diversity, in future commissions for the city’s arts strategy, events and creative programmes, blue plaque and other cultural activities; 1.4 Compile and continuously refresh the list of names included in Appendix B, in collaboration with community representatives, to be published and updated, as a reference tool for current and future opportunities in destination/ street naming. -

15 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

15 bus time schedule & line map 15 Swansea - Waunarlwydd via Uplands, Cockett View In Website Mode The 15 bus line (Swansea - Waunarlwydd via Uplands, Cockett) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Gowerton: 4:00 PM (2) Swansea: 7:50 AM - 4:31 PM (3) Waunarlwydd: 9:00 AM - 5:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 15 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 15 bus arriving. Direction: Gowerton 15 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Gowerton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 4:00 PM Bus Station V, Swansea Tuesday 4:00 PM Christina Street B, Swansea Christina Street, Swansea Wednesday 4:00 PM St George Hotel 1, Swansea Thursday 4:00 PM 127 Walter Road, Swansea Friday 4:00 PM Belgrave Court 1, Uplands Saturday Not Operational Post O∆ce 1, Uplands 33-35 Uplands Crescent, Swansea Victoria Street, Uplands 15 bus Info Direction: Gowerton Post O∆ce, Uplands Stops: 32 Glanmor Road, Swansea Trip Duration: 31 min Line Summary: Bus Station V, Swansea, Christina Glanmor Road, Uplands Street B, Swansea, St George Hotel 1, Swansea, Belgrave Court 1, Uplands, Post O∆ce 1, Uplands, Sketty Avenue, Sketty Victoria Street, Uplands, Post O∆ce, Uplands, Glanmor Road, Uplands, Sketty Avenue, Sketty, Swansea College, Cwm Gwyn Swansea College, Cwm Gwyn, Hillhouse Hospital, Vivian Road, Swansea Cwm Gwyn, Cockett Inn, Cockett, Fry's Corner, Cockett, St Peter`S Church, Cockett, Station, Cockett, Hillhouse Hospital, Cwm Gwyn Cwmbach Road, Cockett, Woodlands, Waunarlwydd, Gypsy Cross, Waunarlwydd, Village -

Geographical Indications: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb

SPECIFICATION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1151/2012 on protected geographical indications and protected designations of origin “Gower Salt Marsh Lamb” EC No: PDO (X) PGI ( ) This summary sets out the main elements of the product specification for information purposes. 1 Responsible department in the Member State Defra SW Area 2nd Floor Seacole Building 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF Tel: 02080261121 Email: [email protected] 2 Group Name: Gower Salt Marsh Lamb Group Address: Weobley Castle, Llanrhidian Gower SA3 1HB Tel.: 01792 390012 e-mail:[email protected] Composition: Producers/processors (6) Other (1) 3 Type of product Class 1.1 Fresh Meat (and offal) 4 Specification 4.1 Name: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ 4.2 Description: ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is prime lamb that is born reared and slaughtered on the Gower peninsular in South Wales. It is the unique vegetation and environment of the salt marshes on the north Gower coastline, where the lambs graze, which gives the meat its distinctive characteristics. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is a natural seasonal product available from June until the end of December. There is no restriction on which breeds (or x breeds) of sheep can be used to produce ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’. However, the breeds which are the most suitable, are hardy, lighter more agile breeds which thrive well on the salt marsh vegetation. ‘Gower Salt Marsh Lamb’ is aged between 4 to 10 months at time of slaughter. All lambs must spend a minimum of 2 months in total, (and at least 50% of their life) grazing the salt marsh although some lambs will graze the salt marsh for up to 8 months. -

London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea

London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea. Archaeological Building Investigation & Recording By Richard Scott Jones (BA, MA, MCIfA) May 2019 HRSWales Report No: 208 Archaeological Building Investigation & Recording London House, Beach Road, Penclawdd, Swansea. By Richard Scott Jones (BA Hons, MA, MCIfA) Prepared for: Mr Adam Rewbridge J.A. Rewbridge Development Services 5 Chapel Street Mumbles Swansea SA3 4NH On behalf of: Mr and Mrs Banfield Date: May 2019 HRSW Report No: 208 H e r i t a g e Recording Services Wales Egwyl, Llwyn-y-groes, Tregaron, Ceredigion SY25 6QE Tel: 01570 493759 Fax: 08712 428171 E-mail: [email protected] Contents i) List of Illustrations and Photo plates Executive Summary Page i 1. Introduction Page 01 2. Methodology and Consultations Page 02 Appendix I: Figures Appendix II: Photo plates Appendix III: Archive Cover Sheet Copyright Notice: Heritage Recording Services Wales retain copyright of this report under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, and have granted a licence to the Mr and Mrs Banfield to use and reproduce the material contained within. The Ordnance Survey have granted Heritage Recording Services Wales a Copyright Licence (No. 100052823) to reproduce map information; Copyright remains otherwise with the Ordnance Survey. i) List of Illustrations Figures Fig 01: Location map (OS Landranger 50,000). Fig 02: Location Map (OS Explorer 1:25,000). Fig 03: Location Block Plan Fig 04: Existing Elevations and Floor Plans Fig 05: Penclawdd Conservation Area Fig 06: Photo Index Plan Photo Plates -

1262 Carmarthen Road, Fforestfach SA5 4BW

1262 Carmarthen Road, Fforestfach SA5 4BW Offers in the region of £279,999 • Four Bedroom Detached Property • Larger Than Average Garden • Potential To Extend (STP) • No Chain • EPC Rating TBA John Francis is a trading name of Countrywide Estate Agents, an appointed representative of Countrywide Principal Services Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. We endeavour to make our sales details accurate and reliable but they should not be relied on as statements or representations of fact and they do not constitute any part of an offer or contract. The seller does not make any representation to give any warranty in relation to the property and we have no authority to do so on behalf of the seller. Any information given by us in these details or otherwise is given without responsibility on our part. Services, fittings and equipment referred to in the sales details have not been tested (unless otherwise stated) and no warranty can be given as to their condition. We strongly recommend that all the information which we provide about the property is verified by yourself or your advisers. Please contact us before viewing the property. If there is any point of particular importance to you we will be pleased to provide additional information or to make further enquiries. We will also confirm that the property remains available. This is particularly important if you are contemplating travelling some distance to view the property. Double glazed window to the DESCRIPTION rear. Access to the loft space. A four bedroom detached bungalow situated on this very BEDROOM 4 pleasant location on 'Old 11'4 x 9'4 (3.45m x 2.84m) Carmarthen Road' with excellent Double glazed window to the links to the M4 motorway at J47 side. -

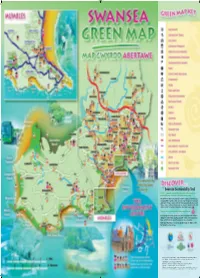

Swansea Sustainability Trail a Trail of Community Projects That Demonstrate Different Aspects of Sustainability in Practical, Interesting and Inspiring Ways

Swansea Sustainability Trail A Trail of community projects that demonstrate different aspects of sustainability in practical, interesting and inspiring ways. The On The Trail Guide contains details of all the locations on the Trail, but is also packed full of useful, realistic and easy steps to help you become more sustainable. Pick up a copy or download it from www.sustainableswansea.net There is also a curriculum based guide for schools to show how visits and activities on the Trail can be an invaluable educational resource. Trail sites are shown on the Green Map using this icon: Special group visits can be organised and supported by Sustainable Swansea staff, and for a limited time, funding is available to help cover transport costs. Please call 01792 480200 or visit the website for more information. Watch out for Trail Blazers; fun and educational activities for children, on the Trail during the school holidays. Reproduced from the Ordnance Survey Digital Map with the permission of the Controller of H.M.S.O. Crown Copyright - City & County of Swansea • Dinas a Sir Abertawe - Licence No. 100023509. 16855-07 CG Designed at Designprint 01792 544200 To receive this information in an alternative format, please contact 01792 480200 Green Map Icons © Modern World Design 1996-2005. All rights reserved. Disclaimer Swansea Environmental Forum makes makes no warranties, expressed or implied, regarding errors or omissions and assumes no legal liability or responsibility related to the use of the information on this map. Energy 21 The Pines Country Club - Treboeth 22 Tir John Civic Amenity Site - St. Thomas 1 Energy Efficiency Advice Centre -13 Craddock Street, Swansea. -

Review of Community Boundaries in the City and County of Swansea

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA FURTHER DRAFT PROPOSALS LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF PART OF COMMUNITY BOUNDARIES IN THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SWANSEA FURTHER DRAFT PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 4. ASSESSMENT 5. PROPOSALS 6. CONSEQUENTIAL ARRANGEMENTS 7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 8. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT 9. THE NEXT STEPS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail: [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 We the Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales (the Commission) are undertaking a review of community boundaries in the City and County of Swansea as directed by the Minister for Social Justice and Local Government in his Direction to us dated 19 December 2007 (Appendix 1). 1.2 The purpose of the review is to consider whether, in the interests of effective and convenient local government, the Commission should propose changes to the present community boundaries. The review is being conducted under the provisions of Section 56(1) of the Local Government Act 1972 (the Act). 1.3 Section 60 of the Act lays down procedural guidelines, which are to be followed in carrying out a review. In line with that guidance we wrote on 9 January 2008 to all of the Community Councils in the City and County of Swansea, the Member of Parliament for the local constituency, the Assembly Members for the area and other interested parties to inform them of our intention to conduct the review and to request their preliminary views by 14 March 2008. -

Local Coal Mines Gowerton, Waunarlwydd, Dunvant

Local coal mines Gowerton, Waunarlwydd, Dunvant Name Source Location comments Opened Owner Men /Abandoned Adair RR On Lliw marsh. Another name for Pwll y Plywf Alltwen JHR/RL/ Alltwen, Cefnstylle Before 1809/c Ysbyty Copper Works, G21 SS 576 963 1888 Llangennech Coal Co (1827) see G 21 Ballarat WmG/ RR Beaufort JHR/RL/ LLwynmawr, Cefnstylle 1867, 3 men Before 1867/ P Richards & Son G21 SS 568 965 suffocated 1879 1867 Glasbrook& Co. BeiliGlas RR Berthlwyd JHR/RL/ Berthlwyd, Penclawdd Before 1719. 1913 David Williams, 130, G21 SS 561 960 Working 1913 Llansamlet, manager M 400 in Williams. See G21 1920 Bishwell WmG/ East of Cefngorwydd Farm 1867, 1 man Before 1754/1887 Padley Bros JHR/RL/ SS 593 952 died See G21 G21 Box WmG Broadoak RR River side in Loughor Bryn RR Brynmawr JHR/RL/ North of Bishwell& Gower Road 1874/1876 Brynmawr Coal Co. G21/ & LNWR railway map SS 595 950 CaeDafydd JHR West of Gower Road 1886/1899 Evans, Loughor SS598 959 CaeLettys JHR Mansel Street, Gowerton Thomas Bros, Loughor CaeShenkyn RR Caedaffyd RL Caergynydd JHR Waunarlwydd Stanley Bros Cape WmG/ SS 604 972 or SS 589 964 1899/1924 Cape Colliery Co. to 1920 sp Ty Gwyn RR/G21 Glasbrook Bros to 1924 CefnBychan RL/G21 SS 542 952 CefnGolau RL/G21 SS 570 959 Cefngoleu JHR Cefnstylle /1884 Pearse Bros from Dunraven No.1 SS 577 955 Estate PMM Page | 1 30/10/2016 Cefngoleu JHR SS 570 960 1905/1922 CefnGoleu Colliery Co.(G21) No.2 Aeron Thomas(JHR) Cefngorwydd JHR/RR North of CefngorwyddFawr Padley Bros No 1 Cefngorwydd JHR East of CefngorwyddFawr No 2 Coalbrook RR Cwm y Glo RL/G21 SS 590 941 /1930 Cwmbach RL SS 628 952 Cwmbaci RR Cyntaf RL Danygraig RR Dan y Lan RL/G21 SS 557 958 Before 1878/ before 1896 Duffryn Gower RL Dunvant WmG/ SS 596 937 Before 1873/1905 S Padley to 1873 RL/G21 Reopened to serve Philip Richard to 1905 Penlan Brickworks 1908 DunvantPenla RL/G21 SS 595 937 1906 Working 1913 Dunvant-Penlan Colliery Co. -

NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11

National Landscape Character 31/03/2014 NLCA39 GOWER © Crown copyright and database rights 2013 Ordnance Survey 100019741 Penrhyn G ŵyr – Disgrifiad cryno Mae Penrhyn G ŵyr yn ymestyn i’r môr o ymyl gorllewinol ardal drefol ehangach Abertawe. Golyga ei ddaeareg fod ynddo amrywiaeth ysblennydd o olygfeydd o fewn ardal gymharol fechan, o olygfeydd carreg galch Pen Pyrrod, Three Cliffs Bay ac Oxwich Bay yng nglannau’r de i halwyndiroedd a thwyni tywod y gogledd. Mae trumiau tywodfaen yn nodweddu asgwrn cefn y penrhyn, gan gynnwys y man uchaf, Cefn Bryn: a cheir yno diroedd comin eang. Canlyniad y golygfeydd eithriadol a’r traethau tywodlyd, euraidd wrth droed y clogwyni yw bod yr ardal yn denu ymwelwyr yn eu miloedd. Gall y priffyrdd fod yn brysur, wrth i bobl heidio at y traethau mwyaf golygfaol. Mae pwysau twristiaeth wedi newid y cymeriad diwylliannol. Dyma’r AHNE gyntaf a ddynodwyd yn y Deyrnas Unedig ym 1956, ac y mae’r glannau wedi’u dynodi’n Arfordir Treftadaeth, hefyd. www.naturalresources.wales NLCA39 Gower - Page 1 of 11 Erys yr ardal yn un wledig iawn. Mae’r trumiau’n ffurfio cyfres o rostiroedd uchel, graddol, agored. Rheng y bryniau ceir tirwedd amaethyddol gymysg, yn amrywio o borfeydd bychain â gwrychoedd uchel i gaeau mwy, agored. Yn rhai mannau mae’r hen batrymau caeau lleiniog yn parhau, gyda thirwedd “Vile” Rhosili yn oroesiad eithriadol. Ar lannau mwy agored y gorllewin, ac ar dir uwch, mae traddodiad cloddiau pridd a charreg yn parhau, sy’n nodweddiadol o ardaloedd lle bo coed yn brin. Nodwedd hynod yw’r gyfres o ddyffrynnoedd bychain, serth, sy’n aml yn goediog, sydd â’u nentydd yn aberu ar hyd glannau’r de. -

Fedex UK Locations Fedex UK Locations

FedEx UK Locations FedEx UK Locations FedEx UK stations Location Opening hours 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Aberdeen Unit 1, Aberdeen One Logistics Park, Crawpeel Road, Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen, AB12 3LG 09:00-12:00 Sat 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Alton Plot 3 Caker Stream Road, Mill Lane Industrial Estate, Alton, Hampshire, GU34 2QA 09:00-12:00 Sat 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Holly Lane Industrial Estate, Atherstone, CV9 2RY Atherstone 09:00-12:00 Sat Unit 1000 Westcott Venture Park, Westcott, Aylesbury, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Aylesbury Buckinghamshire, HP18 0XB 09:00-12:00 Sat Unit A, St Michaels Close, Maidstone, Kent, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Aylesford ME20 7BU 09:00-12:00 Sat 2 Thames Road, Barking, Essex 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Barking IG11 0HZ 09:00-12:00 Sat 1B Whitings Way, London Industrial Park, London, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Beckton E6 6LR 09:00-12:00 Sat 22A Kilroot Business Park, Carrickfergus, Belfast, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Belfast BT38 7PR 09:00-12:00 Sat 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Unit 8 The Hub, Nobel Way, Witton, Birmingham B6 7EU Birmingham 09:00-12:00 Sat 15 Lysander Road, Cribbs Causeway, Bristol, Avon, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Bristol BS10 7UB 09:00-12:00 Sat 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Abbot Close, Byfleet, KT14 7JT Byfleet 09:00-12:00 Sat For help and support: Visit: https://www.fedex.com/en-gb/customer-support.html And chat with our support team 2 FedEx UK Locations FedEx UK stations Location Opening hours 3 Watchmoor Point, Watchmoor Road, Camberley, Surrey, 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Camberley GU15 3AD 09:00-12:00 Sat 09:00-19:00 Mon-Fri Cambridge 43 St Peters Road, -

Seven Year Progress Review of the Swansea Environment Strategy – November 2014 2

time to change: SSEEVVEENN YEARS ON 2014 PROGRESS REVIEW OF THE SWANSEA ENVIRONMENT STRATEGY November 2014 Executive Summary 3 Introduction and Overview 4 Action Plans 4 Indicators 4 Assessment Process 5 Review of Strategic Priorities NE1: Establish and maintain data on the natural environment and monitor change 6 NE2: Protect and safeguard our valued natural assets and halt loss of biodiversity 7 NE3: Maintain and enhance the quality and diversity of the natural environment 9 NE4: Promote awareness, access and enjoyment of the natural environment 12 BE1: Improve the quality and attractiveness of the city centre, other settlements, neighbourhoods and streetscapes 15 BE2: Promote sustainable buildings and more efficient use of energy 17 BE3: Ensure the supply of high-quality, affordable and social housing within mixed, settled and inclusive communities 20 BE4: Protect and promote historic buildings and heritage sites 22 WM1: Protect and improve river and ground water 25 WM2: Maintain and improve bathing and drinking water quality 26 WM3: Restrict development on flood plains, reduce flood risk and improve flood awareness 28 WM4: Restore contaminated land ensuring minimum risks to the environment and public health 29 WM5: Reduce waste going to landfill and increase reuse, recycling and composting 30 WM6: Identify suitable sites and sustainable technologies for dealing with waste 34 ST1: Promote more sustainable forms of travel and transport 35 ST2: Improve access to services, workplaces and community facilities 38 ST3: Improve air quality