Lesson 1A – Human Mercy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HE WILL COME to US LIKE RAIN Hosea 6:1-3 During the 1930'S

HE WILL COME TO US LIKE RAIN Hosea 6:1-3 During the 1930’s there was a drought that lasted nine years. Poor agricultural practices and years of sustained drought took the fertile and productive breadbasket of our nation and turned it into a “dustbowl.” The grasslands of the plains had been deeply plowed and planted to wheat. During the years when there was adequate rainfall, the land produced bountiful crops. But as the droughts of the early 1930s deepened, the farmers kept plowing and planting and nothing would grow. The ground cover that once held the soil in place was gone. The winds whipped across the plains raising billowing clouds of dust to the skies. The skies could darken for days, and in some places the dust would drift like snow, covering farmsteads completely. By 1934, thirty-four states were experiencing serious drought conditions. On Sunday April 14th a small dust storm turned into a black blizzard into a raging storm that would be remembered as “Black Sunday,” a day when thousands of acres of topsoil were literally blown away. The breadbasket of our nation was decimated and times of great desperation fell upon all of those who relied on the land for their livelihood. 1 In his 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck wrote; "And then the dispossessed were drawn west- from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, New Mexico; from Nevada and Arkansas, families, tribes, dusted out. Car- loads, caravans, homeless and hungry; twenty thousand and fifty thousand and a hundred thousand and two hundred thousand. They streamed over the mountains, hungry and restless - restless as ants, scurrying to find work to do - to lift, to push, to pull, to pick, to cut - anything, any burden to bear, for food. -

Hosea an Inspiring Quote the Book of Hosea Who Wrote This Book?

Hosea The prophet Hosea in the 8th century BCE protested violently against Israelite religious practices. An inspiring quote “For I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God rather than burnt offerings” (Hosea 6:6). The Book of Hosea Hosea came from the north and preached at the same time as Amos. He discovered the tenderness of God through personal experience. He loved his wife, although she behaved badly towards him; through his love he succeeded in restoring to her the feelings she had had when she was young. This is how God loves us: not because we are good, but so that we can become good (Hosea 1-3). The book begins with God’s command to Hosea to marry an unfaithful wife who he loved passionately and the first few chapters describe what happened when he did so. Chapter 4 onwards contains a range of messages from God via Hosea, first to the people of Israel (chapters 4-11) and then to the people of Israel and Judah (chapters 11-14), about the anger God felt because of their betrayal of him through injustice, corruption and their worship of other gods. Woven between these messages of doom are some messages of hope, pointing to what God’s people can look forward to beyond the times of trouble. Who wrote this book? The author is announced as Hosea in verses 1:1-2. He was a prophet to the Northern Kingdom of Israel. Hosea, in Hebrew, means salvation but Hosea is popularly termed “the prophet of doom”. -

Hosea 6:1-11

Hosea6_Leviticus_Notes 9/12/18, 10:34 AM Hosea 6:1-11 (Hosea 6:2-11 was also previously the Haftarah for Gen. 42:18 – 43:13) Really starts with the previous verse: Hosea 5:15 - "I will go and return to my place, till they acknowledge their offence, and seek my face: in their affliction they will seek me early." The Septuagint and other translations add "saying..." - i.e. this is what they will say if they repent: Hosea 6:1-2 - "Come, and let us return unto the LORD: for he hath torn, and he will heal us; he hath smitten, and he will bind us up. After two days will he revive us: in the third day he will raise us up, and we shall live in his sight." “Revive” is “chayah” and can mean either to preserve someone alive, restore the dying back to life, or restore the dead to physical life (Deuteronomy 32:39, 1 Samuel 2:6). - Deuteronomy 32:39 - "I kill, and I make alive (chayah); I wound, and I heal" His tearing is in order to heal, and his smiting in order to bind up. “bind us up” = chabash - to tie, bind, bind up, bandage Same word as in Isaiah 1:6 - Isaiah 1:6 - “From the sole of the foot even unto the head there is no soundness in it; but wounds, and bruises, and putrifying sores: they have not been closed, neither bound up, neither mollified with ointment.” - Isaiah 30:26 - He will "bind up the breach of his people, and heal the stroke of their wound" Rashi - "two days" - He will strengthen us from the two retributions which have passed over us from the two sanctuaries that were destroyed. -

Session 3 (Hosea 6.7-8.14)

Tuesday Evening Bible Study Series #8: The Minor Prophets Session #3: Hosea 6:7 – 8:14 Tuesday, January 17, 2017 Outline A. The Prophecies of Hosea (4:1 – 14:9) 1. An agenda of accusations (6:7 – 7:16) a. An unholy gazetteer (6:7-11a) b. A corrupt people and government (6:11b – 7:7) c. Mixing, religious and political, is bad (7:8-16) 2. The crisis and its cause (8:1-14) a. For the crime of assimilating foreign political models and religious practices, the punishment is foreign domination. Notes An agenda of accusations (6:7 – 7:16) • A compilation of sayings to specify the ways that steadfast love of the Lord is lacking in Israel. • 6:7-7:2 – a list of evils occurring at various places in Israel. o 6:7 – Adam was a town in central Transjordan, close to where the Israelites crossed the Jordan (Joshua 3:16). There they transgressed the covenant made with Abraham. o 6:9 – Shechem was the location of an ancient sanctuary to Yahweh. Priests were known to harass pilgrims who visited it. o 6:10 – “whoredom” = metaphor for worship of Baal. o 7:2 – “deeds” are what the Lord sees when Israel appeals for help. • 7:3-7 – Royal politics in Israel is driven by a passion that is constant and is renewed as an oven fire. o 7:3 – The king may refer to Hoshea (732-724 BC), who gained the throne through wickedness and treachery. o 7:4 – “Adulterers” may refer to refer to those who were politically disloyal. -

Hosea: God's Persistent Love

Lesson 1 Hosea: God’s Persistent Love July 4, 2021 Background Scripture Hosea 1, 4, 6 Lesson Passage: Hosea 1:2-10; 4:1-6; 6:4-11 (HCSB) Introduction: Hosea, whose name means salvation, or deliverance, was a contemporary of Amos. Hosea was a young preacher in the nation of Israel, the northern kingdom, and he was a contemporary of the prophets Isaiah and Amos. He lived, as we are told in the first verse, during the reigns of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah (kings of Judah, the Southern Kingdom), and during the reign of Jeroboam. Jeroboam was one of the wicked kings of Israel and the nation was going through a difficult time when Hosea was preaching. Hosea has the distinction as being the last prophet God sent to that nation. The peoples’ conduct was nothing close to that demanded by God. They were guilty of swearing, breaking faith, murder, stealing, committing adultery, deceit, lying, drunkenness, dishonesty in business, and other crimes equally abominable before Jehovah (4:1-2, 11; 6:8-9; 10:4; 13:1-2). The priests were also involved in violence and bloodshed (6:9). The picture painted in the Book of Hosea is truly that of a nation in decay. God was completely left out of the peoples’ thinking. The prophet’s task was to turn the thinking of the people back to God, but they were too deeply steeped in their idolatry to heed his warning. They had passed the point of no return and they refused to hear. The key to Hosea’s prophecy is the parallel of Hosea’s personal life to that of God’s relationship with Israel. -

Hosea 7:1-16 and Destructive Leadership Theory: an Exegetical Study

Hosea 7:1-16 and Destructive Leadership Theory: An Exegetical Study Daniel B. Holmquist Regent University This qualitative hermeneutical study of Hosea 7:1-16 examined Hosea’s insights into leadership and how they might enhance, critique, or refine destructive leadership theory (DLT). After performing a general hermeneutical and genre analysis of the biblical text and uncovering its leadership implications, these implications were intersected with the three domains of the toxic triangle theory of DLT: destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments. Although the situation in Hosea 7 illustrated well the toxic triangle of DLT, a number of areas for potential refinement of DLT emerged, especially related to the theory’s reliance upon modern psychology, ethics, and views of culture. DLT remains in the formative stages of development and could benefit from building stronger ethical foundations, investigating additional processes involved in destructive leadership situations, studying the interaction between the three domains of the toxic triangle, and exploring potential solutions to destructive leadership. Insights from Hosea 7, as well as from additional exegetical research of scripture, show promise for further gains toward a more robust theory of destructive leadership. Many leaders have destroyed their organizations, those associated with them, and even themselves. Researchers have referred to such leaders and their leadership as negative, toxic, dark, and destructive, and have developed various theories of destructive leadership to explain the phenomenon, its dimensions, and its processes. Since researchers have only recently begun to investigate and describe destructive leadership—it is a set of theories under development—this would seem to be an opportune time to bring in exegetical research from Scripture to inform and assist with theory development. -

Daddy, Are We There Yet? First, You Must Acknowledge Guilt

NLPC: Women in the Word Feb 27, 2019 Hosea 6–7, Rebecca Jones Daddy, Are We There Yet? Hosea 6:1–3 a parallel with the 5:13–15: no one to heal; I will tear, go away, carry off; return to my place; no rescue until they acknowledge their guilt and seek my face. 6:1–3: Come, let us return to the LORD; for he has torn us, that he may heal us; he has struck us down, and he will bind us up. After two days he will revive us; on the third day he will raise us up that we may live before him. Let us know; let us press on to know the LORD; his going out is sure as the dawn; he will come to us as the showers, as the spring rains that water the earth. Is there hope for the wicked? Are these words from the people enough to make the lion come out of his lair? The ride will be rough before the children of Israel arrive at their destination. Their loving father is at the wheel, but his righteous anger is not yet appeased. There is something missing in their cry of hope. First, You Must Acknowledge Guilt What Sin? Fickle in their love, which is gone like the marine layer or morning mist (6:4) Ritualistic in their worship, not true worship (6:6) Faithless to their covenant (6:7) Violent and bloody robbers, thieves, adulterers, bandits and murderers (6:8–10) Treacherous liars (7:1) Angry mockers (7:5–6) King-killers (devour their rulers) (7:7) Syncretists who mix pagan religions with worship of the true God (7:8) Wanderers from God (7:13) and rebellious children (7:13) Self-pitying whiners who won’t repent (7:14) Worshipers who use pagan religious practices -

Hosea 6 Resources

Hosea 6 Resources Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Click chart to enlarge OUTLINE OF HOSEA I. The Prodigal Wife, Hosea 1:1-3:5 A. Her Unfaithfulness, Hosea 1:1-11 B. Her Punishment, Hosea 2:1-13 C. Her Restoration and Israel's, Hosea 2:14-23 D. Her Redemption, Hosea 3:1-5 II. The Prodigal People, Hosea 4:1-14:9 A. The Message of Judgment, Hosea 4:1-10:15 1. The indictment, Hosea 4:1-19 2. The verdict, Hosea 5:1-15 3. The plea of Israel, Hosea 6:1-3 4. The reply of the Lord, Hosea 6:4-11 5. The crimes of Israel, Hosea 7:1-16 6. The prophecy of judgment, Hosea 8:1-10:15 B. The Message of Restoration, Hosea 11:1-14:9 1. God's love for the prodigal people, Hosea 11:1-11 2. God's chastisement of the prodigal people, Hosea 11:12-13:16 3. God's restoration of the prodigal people, Hosea 14:1-9 Ryrie Study Bible ALBERT BARNES NOTES Be a Berean - Not Always Literal especially in prophetic passages. Hosea 6 Commentary W J BEECHER The Prophets and the Promise - 433 Page Book BIBLICAL ILLUSTRATOR Be a Berean - Not Always Literal especially in prophetic passages. Hosea 6 Commentary BRIAN BELL Calvary Chapel Conservative, Literal Interpretation Hosea 5,6 The Moth, The Rot, &The Lion! BIBLE.ORG RESOURCES Resources that Reference Hosea Hosea 6 BRIDGEWAY BIBLE COMMENTARY Hosea 6 JEREMIAH BURROUGHS Hosea - Exposition of the Prophecy of Hosea JOHN CALVIN Commentary on Hosea Note: Calvin's prayers are excellent, and are very convicting - Suggestion: Read them aloud, very slowly and as a sincere prayer to the Almighty God. -

Hosea 7:1-16

a Grace Notes course Hosea by Rev. Mark Perkins, Pastor Denver Bible Church, Denver, Colorado Lesson 10 Hosea 7:1-16 Grace Notes 1705 Aggie Lane, Austin, Texas 78757 Email: [email protected] Hosea Lesson 10: Hosea 7:1-16 Instructions Lesson 10: Hosea 7:1-16 ................................................................................................... 10-4 Lesson 10 Quiz...................................................................................................................10-11 Instructions for Completing the Lessons Begin each study session with prayer. It is the Holy Spirit who makes spiritual things discernable to Christians, so it is essential to be in fellowship with the Lord during Bible study. Read the whole book of Hosea often. It is a short book, and reading it many times will help you understand the story much better. Instructions 1. Read the introduction to the study of Hosea 2. Study the Hosea passage for this lesson, by reading the verses and studying the notes. Be sure to read any other Bible passages that are called out in the notes. 3. Review all of the notes in the Hosea lesson. 4. Go to the Quiz page and follow the instructions to complete all the questions on the quiz. The quiz is “open book”. You may refer to all the notes and to the Bible when you take the test. But you should not get help from another person. 5. When you have completed the Quiz, be sure to SAVE your file. If your quiz file is lost, and that can happen at Grace Notes as well, you will want to be able to reproduce your work. 6. To send the Quiz back to Grace Notes, follow the instructions on the Quiz page. -

Bible Study the Book of Hosea 6:1-7:16 True and False Repentance

Bible Study The Book of Hosea 6:1-7:16 True and False Repentance Hosea 6:1−7:16 True and False Repentance In chapters six and seven of Hosea the nation of Israel is experiencing some difficult times, and Israel wanted God’s blessings to be restored, but God desired the nation to repent. The discussion for Hosea chapters six and seven will focus on biblical repentance. Biblical repentance goes beyond remorse, regret, or feeling bad about sin; but biblical repentance is a changing of one’s mind about sin and walking in a new direction. As with anything else repentance can be genuine or disingenuous; therefore we must be careful how we approach God. Objectives: To understand biblical repentance. To understand the difference between true and false repentance. To understand the true condition of the nation of Israel. Questions and Answers Hosea 6:1-3 A. Why was the nation of Israel facing such grave circumstances? B. What did the nation of Israel decide to do about their circumstances? (1) C. Why did Israel believe they would be redeemed in 3 days? What as the problem? (2) D. Do you believe Israel was sincere in saying “Come and let us return unto the Lord:”? E. What did Israel desire from the Lord as a result of their repentance, and what do the former and latter rain represent? (3) F. What steps are involved in sincere repentance? G. Israel used all the right words, but why didn’t God accept their repentance? (6:6-8, 7:10, 13, 16a,b) Bible Study The Book of Hosea 6:1-7:16 True and False Repentance Hosea 6:4−7:16 H. -

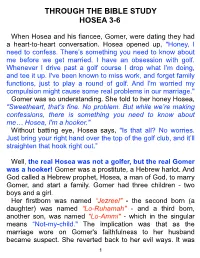

T3246.Hosea 3-6.020817.Pages

THROUGH THE BIBLE STUDY HOSEA 3-6 When Hosea and his fiancee, Gomer, were dating they had a heart-to-heart conversation. Hosea opened up, "Honey, I need to confess. There’s something you need to know about me before we get married. I have an obsession with golf. Whenever I drive past a golf course I drop what I'm doing, and tee it up. I've been known to miss work, and forget family functions, just to play a round of golf. And I'm worried my compulsion might cause some real problems in our marriage." Gomer was so understanding. She told to her honey Hosea, "Sweetheart, that’s fine. No problem. But while we’re making confessions, there is something you need to know about me… Hosea, I'm a hooker." Without batting eye, Hosea says, "Is that all? No worries. Just bring your right hand over the top of the golf club, and it’ll straighten that hook right out.” Well, the real Hosea was not a golfer, but the real Gomer was a hooker! Gomer was a prostitute, a Hebrew harlot. And God called a Hebrew prophet, Hosea, a man of God, to marry Gomer, and start a family. Gomer had three children - two boys and a girl. Her firstborn was named “Jezreel" - the second born (a daughter) was named “Lo-Ruhamah" - and a third born, another son, was named "Lo-Ammi" - which in the singular means “Not-my-child." The implication was that as the marriage wore on Gomer's faithfulness to her husband became suspect. -

Hosea 6:4-7:16 the Covenant Love of God and the Idolatry of His People

Hosea 6:4-7:16 The Covenant Love of God and The Idolatry of His People I. Introduction/review A. Structure of 4:1-14:9:1 1. 4:1-6:3 — Evidence of ignorance of God and statement of hope 2. 6:4-11:11 — Evidence of disloyalty to God and statement of hope 3. 11:12-14:9 — Evidence of faithlessness to God and statement of hope II. 6:4-11 — Empty religion and a guilty people A. 4-6 — Israel’s empty religion and lack of hesed love 1. 4 — Despite the plea to his people to return, Israel’s response contradicts the faithfulness of Yahweh. Instead of turning to him in true hesed love, their hesed love is like a morning mist that vanishes. This explains the exasperation of Yahweh, “What shall I do with you, O Ephraim?” “What shall I do with you, O Judah?” Do any of you have a similar reaction to your children? 2. 5 2— In response to their empty religion Yahweh sent his messengers, the prophets, to proclaim His Word. These words had the effect of hewing and slaying them, in the sense that it showed the judgment that would be coming if they did not repent. The people were without excuse, for Yahweh had shown them their errors. McComiskey writes, “No Israelite could say that the demise of the nation was due only to the fortuitous course of national events or the caprices of foreign kings.”3 They were going to face judgement from Yahweh because of the absence of hesed love.