The Internet and Firearms Research with Reference to the .43 Spanish Remington Rolling-Block and Its Ammunition David A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. General Penalty, Town Actions/Citation/Administrative Appeal

I. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Amend Chapter 3 to read: a. General Penalty, Town Actions/Citation/Administrative Appeal 2. Amend to add Chapter 12 to read: II. Firearm Discharge 105 CHAPTER 12 FIREARM DISCHARGE SECTION 1 TITLE AND PURPOSE: The Town Board of Johnson has determined that the health, safety and general welfare of a person is threatened when a person discharges a firearm within those areas of the Town used for residential or commercial purpose, or within one hundred (100) yards therefrom. The Town Board, therefore, establishes an Ordinance regulating the discharge of firearms for certain areas within the Town consistent with Wisconsin State Statutes, including §66.0409, §167.31, §895.527, §941.20 and §948.605. SECTION 2 AUTHORITY: The Town Board has the specific authority granted under the Village Powers of the Town Board, pursuant to Sec. §60.10(2)(c), §60.22 of the Wisconsin Statutes, and pursuant to Sec. §60.23 of the Wisconsin Statutes. SECTION 3 ADOPTION: This Ordinance adopted by a majority vote of the Town Board on roll call vote with a quorum present and voting, and proper notice having been given, provides for the imposition of an Ordinance restricting the discharge of firearms within certain areas in the Town of Johnson (hereinafter Town), Marathon County. SECTION 4 DEFINITIONS: 1. Residential Purpose: Any area within the Town where there is located a dwelling used or usable for human occupancy. 2. Commercial Purpose: Any area within the Town where there is located a structure and its appurtenances, used or usable for the purpose of carrying on any trade, industry or business, except for such areas which are twenty (20) acres or more in size, which are used for agricultural purposes, and which are more than one hundred (100) yards from a residential or commercial area. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Wood, Christopher Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Original Citation Wood, Christopher (2013) Were the developments in 19th century small arms due to new concepts by the inventors and innovators in the fields, or were they in fact existing concepts made possible by the advances of the industrial revolution? Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/19501/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Were the developments in 19th century small -

4-H Shooting Sports an Introduction to Muzzleloading Firearms

4-H Shooting Sports An Introduction to Muzzleloading Firearms A buckskin-clad hunter in a skunk skin hat slips quickly along a woodland trail. Suddenly he freezes, shoulders his flintlock rifle, and fires. As the cloud of white smoke clears, he notes the bullet has hit well. No, he’s not a frontiersman of long ago; he is a member of an emerging group of modern shooters and hunters— those who prefer to use muzzleloading firearms in the pursuit of their sport. American history is deeply intertwined with the development of firearms, and improved muzzleloading arms were key elements in the nation’s develop - ment. The West, land west of the Appalachian Mountains, was opened by hardy frontiersmen carrying Kentucky (or Pennsylvania) rifles. Their long, light, and accurate rifles were adequate when wildlife up to the size of white-tailed deer and bears were staples of the frontier diet. Those rifles were inadequate for the Louisiana expedition led by Lewis and Clark. Bison and grizzly bears required heavier loads with larger bullets, and horseback travel made a shorter rifle desir - able. The Hawken plains rifle answered that need and served the mountainmen who explored the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains. Only when breechloading arms were developed in the middle of the 19th cen - tury did muzzleloaders begin to decline. The superior loading speed and conven - ience of the breechloader made them more desirable. Now, a century later, shoot - ers are rediscovering muzzleloading arms—reliving history and having fun. Let’s look at these arms and how to use them. Objectives To help students understand and experience: • Muzzleloading terminology and names • Black powder and lead balls • Equipment required • Additional safety procedures involved in black powder handling and muzzle - loader shooting • Loading and firing procedures and principles • Cleaning procedures Teaching Time 2 hours (varies with number of students, instructors, and firearms) Materials You also need a short and long starter, normally As any muzzleloading shooter knows, there are combined in one tool. -

A Short History of Firearms

Foundation for European Societies of Arms Collectors A short history of firearms Prepared for FESAC by: , ing. Jaś van Driel FARE consultants P.O. box 22276 3003 DG Rotterdam the Netherlands [email protected] Firearms, a short history The weapon might well be man’s earliest invention. Prehistoric man picked up a stick and lashed out at something or someone. This happened long before man learned to harness fire or invented the wheel. The invention of the weapon was to have a profound impact on the development of man. It provided the third and fourth necessities of life, after air and water: food and protection. It gave prehistoric man the possibility to hunt animals that were too big to catch by hand and provided protection from predators, especially the greatest threat of all: his fellow man. The strong man did not sit idly while intelligent man used the weapon he invented to match his brute force and soon came up with a weapon of his own, thus forcing intelligent man to come up with something better. The arms race had started. This race has defined the history of mankind. To deny the role that weapons in general and firearms in particular have played in deciding the course of history is like denying history itself. The early years During the Stone Age axes, knives and spears appeared and around 6000 BC the bow made its debut. This was the first weapon, after the throwing spear, that could be used at some distance from the intended target, though possibly slings also were used to hurl stones. -

Ignition Potential of Muzzle-Loading Firearms an Exploratory Investigation

U.S. Department of Agriculture Ignition Potential Forest Service of Muzzle-Loading National Technology & Development Program Firearms 5100—Fire Management 0951 1802—SDTDC April 2009 An Exploratory Investigation EST SERVIC FOR E D E E P R A U RTMENT OF AGRICULT Ignition Potential of Muzzle-Loading Firearms An Exploratory Investigation David V. Haston, P.E., Mechanical Engineer National Technology and Development Program, San Dimas, CA Mark A. Finney, Ph.D., Research Forester Rocky Mountain Research Station Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT Andy Horcher, Ph.D., Forest Management Project Leader National Technology and Development Program, San Dimas, CA Philip A. Yates, Ph.D., Assistant Professor Department of Mathematics and Statistics California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA Kahlil Detrich, Graduate Student, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA April 2009 Information contained in this document has been developed for the guidance of employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, its contractors, and cooperating Federal and State agencies. The USDA Forest Service assumes no responsibility for the interpretation or use of this information by other than its own employees. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official evaluation, conclusion, recommendation, endorsement, or approval of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. -

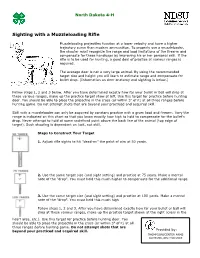

Sighting with a Muzzleloading Rifle

North Dakota 4-H Sighting with a Muzzleloading Rifle Muzzleloading projectiles function at a lower velocity and have a higher trajectory curve than modern ammunition. To properly use a muzzleloader, the shooter must recognize the range and load limitations of the firearm and compensate for these handicaps by improving his or her personal skill. If the rifle is to be used for hunting, a good deal of practice at various ranges is required. The average deer is not a very large animal. By using the recommended target size and height you will learn to estimate range and compensate for bullet drop. (Information on deer anatomy and sighting is below.) Follow steps 1, 2 and 3 below. After you have determined exactly how far your bullet or ball will drop at these various ranges, make up the practice target show at left. Use this target for practice before hunting deer. You should be able to place the projectile in the cross (or within 3" of it) at all three ranges before hunting game. Do not attempt shots that are beyond your practiced and acquired skill. Skill with a muzzleloader can only be acquired by constant practice with a given load and firearm. Vary the range is indicated on this chart so that you know exactly how high to hold to compensate for the bullet's drop. Never attempt to hold at some undefined point above the back line of the animal (top edge of target). Such shooting is dependent on luck, not skill. Steps to Construct Your Target 1. Adjust rifle sights to hit "dead-on" the point of aim at 50 yards. -

Silencerco Maxim® 50 Instruction Manual

TM SILENCERCO MAXIM® 50 INSTRUCTION MANUAL Thank you for choosing to add a SilencerCo Maxim® 50 to your collection. We are proud to ® deliver only the best to our community and hope you will enjoy using this product as much as WE AT SILENCERCO HOPE THAT YOU ENJOY THE we enjoyed making it. Welcome to the SilencerCo family. TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCEMENTS OFFERED BY THE MAXIM 50. TO PROVIDE FOR YOUR SAFETY AND THE Sincerely and Silently, EFFECTIVE USE OF THIS PRODUCT, IT IS CRITICAL THAT THE OWNER AND ANY USER OF THIS PRODUCT READ THE ENTIRE MANUAL AND FOLLOW STRICTLY Joshua Waldron THE WARNINGS AND INSTRUCTIONS WITHIN. THIS SilencerCo Co-Founder & CEO PRODUCT IS INTENDED TO BE USED ONLY BY THOSE WHO ARE WELL-VERSED IN THE SAFE OPERATION OF MUZZLELOADERS. TABLE OF CONTENTS BASICS FUNCTION & OPERATION MAINTENANCE 1 / WARNING 25 / SAFETY FEATURES 53 / CLEANING & MAINTENANCE 2 / MODERN MUZZLELOADING 26 / FUNCTION TEST 55 / FIELD STRIPPING & CLEANING 3 / SPECS 29 / INITIAL CLEANING 57 / DETAILED DISASSEMBLY 5 / FEATURES IDENTIFICATION 33 / TESTING THE IGNITION 61 / DETAILED CLEANING 7 / EQUIPMENT 35 / LOADING THE CHARGE 65 / BREECH PLUGS 9 / BLACK POWDER GUIDELINE 37 / LOADING THE PROJECTILE 41 / PRIMING SAFETY 43 / FIRING SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 13 / USER RESPONSIBILITIES 45 / MISFIRES & HANGFIRES 69 / TROUBLESHOOTING 19 / SAFE STORAGE & TRANSPORTATION 47 / UNLOADING & UNCHARGING 70 / WARRANTY 21 / SAFETY & OPERATION 49 / OPTICS WARNING MODERN MUZZLELOADING Failure to follow installation and maintenance Moderators must be free of obstructions such as More and more sportsmen have discovered the The Maxim 50 represents the latest developments instructions detailed in this manual may result in mud, dirt, etc. -

John Dahlgren the Plymouth Rifle

JOHN DAHLGREN And THE PLYMOUTH RIFLE Marc Gorelick, VGCA The author thanks Tim Prince of College Hill Arsenal (www.collegehillarsenal.com) and Cliff Sophia of CS Arms (www.csarms.com) for the use of their photographs. Few Americans today know who John Dahlgren was, or the role he played in the Civil War. Most Civil War and navy history buffs who recognize his name identify him as a Union Admiral and ordnance expert who developed a number of naval cannon. Indeed, for his achievements in developing naval cannon he became known as the “father of American naval ordnance.” But to the gun collecting community Dahlgren was also a small arms expert and the inventor of the unique Plymouth Rifle. Photo courtesy Tim Prince, College Hill Arsenal, www.collegehillarsenal.com DAHLGREN’S NAVY CAREER John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren was born on November 13, 1809 in Philadelphia, the son of Bernhard Ulrik Dahlgren, the Swedish Consul in Philadelphia. Like another Swedish-American, John Ericsson, the inventor of the screw propeller, turret and ironclad monitor, Dahlgren was to have a profound effect on the U.S. Navy. Dahlgren joined the United States Navy in 1826 as a midshipman. He served in the U.S. Coastal Survey from 1834 to 1837 where he developed his talents for mathematics and scientific theory. He was promoted to lieutenant, and after a number of cruises was assigned as an ordnance officer at the Washington Navy Yard in 1847. Dahlgren was in his element as an ordnance officer. He excelled as a brilliant engineer and was soon given more and more responsibility. -

Deadlands Armory’S “Breech-Loading Rifles” Page for a History of Westley Richards.)

Handguns Part II. Breech-Loading Single-Shot Pistols Breech-Loading The mid-nineteenth century was a time of great innovation in the field of firearms. People began the century dueling with the same flintlock pistols as their fathers and grandfathers, and ended with a plethora of options including caplocks, single-shot breech-loaders, pepperbox pistols, revolvers, and the first magazine-fed semi-automatics. By the time breech-loading rifles began to supplant muzzle-loaders in the early 1860s, most handguns were already using some form of revolving cylinder. Still, a few breech-loading pistols made their way to the market, particular those designed by Frank Wesson, Joshua Stevens, and Remington. Like their larger cousins, such pistols require some form of mechanical action to open the breech, chamber the round, and reseal the breech. Because handguns do not require the same range and accuracy as rifles, creating an effective system of “obturation”—sealing the breech during discharge to prevent the escape of hot gas—is not as important to pistols as it is to rifles and carbines. Frank Wesson’s “tip-up” loading Rollin White Pistol “swivel down” loading COPYRIGHT 2018 BY A. BUELL RUCH. PAGE 1 OF 23 Cartridges Another important mid-century innovation was the metal cartridge, in which the bullet, propellant, and primer are encased within the same unit. The round is discharged when the firing pin strikes the base of the cartridge, setting off the primer. Because metal expands when heating, the hot casing forms a gas seal, directing the explosive energy forward. Such cartridges, usually made from brass (and before the mid-1870s, copper) are designated as “rimfire” or “centerfire” depending on where the firing pin strikes the case. -

2021 Muzzleloader Season - DRAFT

2021 Muzzleloader Season - DRAFT Any license and permit that was valid for deer or elk through the general big game season will be valid for that species during the traditional muzzleloader season that runs December 11–19, 2021 per the conditions of that license and permit and regulations pertaining to the hunting district(s) in which the license-permit is valid. With the following exceptions, all other general big game season regulations apply, including in weapons restricted areas. Conditions: Where existing approved seasons are in place that overlap the traditional muzzleloader season, such as elk shoulder seasons, late white-tailed deer seasons and lion seasons, the regulations associated with those approved seasons remain in place. Therefore, there can be overlap between the existing approved season and muzzleloader season (e.g., cow elk only in a shoulder season hunting district using rifles, but bull elk could be taken with traditional muzzleloader in that same hunting district with valid license and permit). Department staff may initiate game damage and management hunts following established policies and using modern firearms, during the traditional muzzleloader season. Many Wildlife Management Areas close on December 1 to protect wintering wildlife. Traditional muzzleloader hunting on those WMAs will not be allowed. Motorized access on many federal lands is closed as of December 1. Hunters must comply with land management agency travel plans. Muzzleloader hunters must use plain lead projectiles and a muzzleloading rifle that is charged with loose black powder, loose pyrodex, or an equivalent loose black powder substitute, and ignited by a flintlock, wheel lock, matchlock, or percussion mechanism using a percussion or musket cap. -

Historic Firearms and Early Militaria: Day 2 November 2, 2016 — Lots 630 - 1484

Historic Firearms and Early Militaria: Day 2 November 2, 2016 — Lots 630 - 1484 Cowan’s Auctions Auction Exhibition Bid 6270 Este Avenue Lots 1 - 623 October 31, 2016 In person, by phone, absentee Cincinnati, OH 45232 November 1, 2016 12 to 5 pm or live online at bidsquare.com 513.871.1670 10 am November 1, 2016 Fax 513.871.8670 Lots 630 - 1484 8 to 10 am November 2, 2016 November 2, 2016 cowans.com 10 am 8 to 10 am Phone and Absentee Bidding 513.871.1670 or visit cowans.com Buyer’s Premium 15% Cowan's Auctions, Inc. DAY TWO - Historic Firearms and Militaria November 2, 2016 Auction begins at 10:00 AM **Please note - all lots marked with asterisks(*) require a Federal Firearms License or a Form 4473 to be completed and background check performed. Successful buyers will not be permitted to leave with the firearm without submitting a FFL or completing the Form 4473. No exceptions. Thank you for your cooperation. Lot Item Title Low Estimate High Estimate 630 Flintlock Yeager Rifle $1,000 $1,500 631 French Flintlock Trade Rifle $700 $1,000 632 Brass Fouled Anchor Flask by N.P. Ames Co $800 $1,200 633 Combination Sword And Flintlock Pistol $1,000 $1,500 634 Hand Held Flintlock Pistol $750 $1,000 635 Pair Of Iron Mounted Blunderbuss Pistols $1,000 $1,500 636 Pair Of Flintlock Blunderbuss Pistols By Alex Thompson $1,500 $2,500 637 Iron Mounted Four Shot Flintlock Pistol $1,500 $2,500 638 Flintlock Powder Tester $1,000 $1,500 639 Flintlock Powder Tester $1,000 $1,500 640 Middle-Eastern Flintlock Blunderbuss Gunbutt Pistol $750 $1,000 641 Middle-Eastern -

Rolling Block Rifle Vs Carcano Rifle

Rolling block rifle vs carcano rifle Continue Sniper Rifles - Rolling Block Rifle Rolling Block Rifle is a very powerful and coded sniper rifle for Red Dead redemption. It's capable of firing targets over long distances with greater ease than other weapons. Description: Carcano Rifle has higher store capacity, higher loading speed and faster shooting rate. However, a Rolling Block Rifle can kill a player with one shot to the head, chest, or abdomen. Unlike the carcano rifle, which can kill with only one shot when in the head. The weapon is so powerful that even at long distances it can literally break a player's jaw. This is directly at odds with this weapon, because the Carcano Rifle has a higher quality than this. It's based on the Remington Rolling Block rifle. This is the first rifle in the game that can get passes on missions and it uses ammunition for a sniper rifle. Info: Singleplayer: Rolling Block Rifle is from The Empty Promises mission given by Vincente de Santa. In addition, the Rolling Block Rifle can also be a Savior's Die? mission, given to Luisa Fortuna. It is located at the top of the castle, where the player climbs on the wall. Alternatively, you can use the cheating code. Multiplayer: Rolling Block Rifle is unlocked when you reach the 20th century. Undead Nightmare: The player gets rifles while cleaning pacific union railroad camp zombies. In addition, the player also receives rifles killing survivors of Blackwater on the roof of one of the buildings. However, if a player kills survivors and takes a gun, zombies have a much better chance of capturing the city.