In the Dust of the Multiverse?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

24 Hours of Anime Antics Some Schooling in the Romance Depart- Courtesy of Seinfeld.Com Ment

November 19, 2002 THE RETRIEVER WEEKLY FEATURES Page 25 Let Downs and Bad Hair Days show began, but had never been able to reveal from TV, page 21 his true feelings for her. After several sea- the air for four weeks in the middle of the sons, he interrupted her wedding plans by winter. When it returned mid-February, telling her the truth and the two began to date much of its audience had gone elsewhere. and eventually set out to elope. This season, 1.The finale of Seinfeld. Never has a tel- they did it. They tied the knot. He got the girl. evision audience felt so betrayed, so outraged, The good guy won. Which is what we all so letdown as the American people did after wanted, right? Sadly, no. It’s not what we wanted at all. What we wanted was to pine away with him, to know that he’s the good guy that deserves the girl, but to continue to enjoy watching him long for her. But he got her. He wins and we lose. No more drama. Interesting that there was drama to begin with; as both Niles and his brother Frasier (Kelsey Courtesy of www.anime.com Grammer) are both psychiatrists, The Unusual Suspects: The cast of the hit anime Cowboy Bebop were some of you’d think that they’d have every- the stars seen at the Anime Marathon. thing about love figured out, when in actuality, up until when Niles got the girl, they were both in serious need of 24 Hours of Anime Antics some schooling in the romance depart- Courtesy of Seinfeld.com ment. -

Horror of Philosophy

978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page i In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page ii 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iii In The Dust of This Planet [Horror of Philosophy, vol 1] Eugene Thacker Winchester, UK Washington, USA 978 1 84694 676 9 In the dust of this planet txt:Layout 1 1/4/2011 3:31 AM Page iv First published by Zero Books, 2011 Zero Books is an imprint of John Hunt Publishing Ltd., Laurel House, Station Approach, Alresford, Hants, SO24 9JH, UK [email protected] www.o-books.com For distributor details and how to order please visit the ‘Ordering’ section on our website. Text copyright: Eugene Thacker 2010 ISBN: 978 1 84694 676 9 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers. The rights of Eugene Thacker as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design: Stuart Davies Printed in the UK by CPI Antony Rowe Printed in the USA by Offset Paperback Mfrs, Inc We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution. -

Ebook Download Seinfeld Ultimate Episode Guide Ebook Free Download

SEINFELD ULTIMATE EPISODE GUIDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dennis Bjorklund | 194 pages | 06 Dec 2013 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781494405953 | English | none Seinfeld Ultimate Episode Guide PDF Book Christmas episodes have also given birth to iconic storylines. Doch das vermeintliche Paradies hat auch seine Macken. Close Share options. The count includes both halves of three one-hour episodes, including the finale , and two retrospective episodes, each split into two parts: " The Highlights of ", covering the first episodes; and " The Clip Show ", also known as "The Chronicle", which aired before the series finale. Doch zuerst geht es um ihr eigenes Zuhause: Mobile 31 Quadratmeter werden auf mehrere Ebenen aufgeteilt. December is the most festive month of the year and plenty of TV shows — both new and old — have Christmas-themed episodes ready to rewatch. Spike Feresten. Finden sie ein Haus nach ihrer Wunschvorstellung - in bezahlbar? Main article: Seinfeld season 1. Cory gets a glimpse at what life would be like without Topanga and learns that maybe it's worth making a few compromises. Das Ehepaar hat in der Region ein erschwingliches Blockhaus mit Pelletheizung entdeckt. Doch noch fehlt ein Zuhause. Doch es wird immer schwieriger, geeignete Objekte auf dem Markt zu finden. Sound Mix: Mono. As they pass the time, the pair trade stories about their lives, which ultimately give clues to their current predicament. Was this review helpful to you? Jason Alexander. Favorite Seinfeld Episodes. Schimmel und ein kaputtes Dach sind nur der Anfang. Auch das Wohn-, Ess- und Badezimmer erstrahlen in neuem Glanz. Deshalb bauen die Do-it-yourself-Experten seinen Keller um. -

SIMPSONS to SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M

CONTEMPORARY ANIMATION: THE SIMPSONS TO SOUTH PARK-FILM 4165 (4 Credits) SPRING 2015 Tuesdays 6:00 P.M.-10:00 P.M. Social Work 134 Instructor: Steven Pecchia-Bekkum Office Phone: 801-935-9143 E-Mail: [email protected] Office Hours: M-W 3:00 P.M.-5:00 P.M. (FMAB 107C) Course Description: Since it first appeared as a series of short animations on the Tracy Ullman Show (1987), The Simpsons has served as a running commentary on the lives and attitudes of the American people. Its subject matter has touched upon the fabric of American society regarding politics, religion, ethnic identity, disability, sexuality and gender-based issues. Also, this innovative program has delved into the realm of the personal; issues of family, employment, addiction, and death are familiar material found in the program’s narrative. Additionally, The Simpsons has spawned a series of animated programs (South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, Rick and Morty etc.) that have also been instrumental in this reflective look on the world in which we live. The abstraction of animation provides a safe emotional distance from these difficult topics and affords these programs a venue to reflect the true nature of modern American society. Course Objectives: The objective of this course is to provide the intellectual basis for a deeper understanding of The Simpsons, South Park, Futurama, Family Guy, and Rick and Morty within the context of the culture that nurtured these animations. The student will, upon successful completion of this course: (1) recognize cultural references within these animations. (2) correlate narratives to the issues about society that are raised. -

Dear Student, June 26, 2014 Welcome to AP Environmental

Dear Student, June 26, 2014 Welcome to AP Environmental Science at School of the Future! During the upcoming school year we will be covering a large range of topics to determine what makes our Earth habitable and how humans impact Earth and its environments. From the very first day, we will also be working towards and preparing for the AP Environmental Science exam given by the College Board in May of 2015. This is an intense course equivalent to a college level introductory environmental science class. To help us hit the ground running next semester, I am asking (and by asking I mean requiring) all APES students to complete the following: 1. Read The World Without Us by Alan Weisman and an environmental science themed novel of your choice (see below for suggestions). Then use what you have learned from these books to develop and support (with textual evidence) a nuanced claim in response to this question, “Is humankind bad for the Earth?” Think about the impacts that humans have had on Earth, its environments, and the other organisms that inhabit them. Is the impact good? Bad? Somewhere in between? Are there efforts that humans can make to change their impact upon the Earth? Keep these questions in mind while reading and writing. NOTE: The fictional selections below don’t always take place on Earth so feel free to interpret “Earth” as “the planet humans are living on.” Your essay should be at least three pages in length and contain APA/MLA formatted citations as well as a biography. A paper copy of the completed essay is due in class on Thursday, September 4th. -

Wendy's® Expands Partnership with Adult Swim on Hit Series Rick and Morty

NEWS RELEASE Wendy's® Expands Partnership With Adult Swim On Hit Series Rick And Morty 6/15/2021 Fans Can Enjoy New Custom Coca-Cola Freestyle Mixes and Free Wendy's Delivery to Celebrate Global Rick and Morty Day on Sunday, June 20 DUBLIN, Ohio, June 15, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Wubba Lubba Grub Grub! Wendy's® and Adult Swim's Rick and Morty are back at it again. Today they announced year two of a wide-ranging partnership tied to the Emmy ® Award-winning hit series' fth season, premiering this Sunday, June 20. Signature elements of this season's promotion include two new show themed mixes in more than 5,000 Coca-Cola Freestyle machines in Wendy's locations across the country, free Wendy's in-app delivery and a restaurant pop-up in Los Angeles with a custom fan drive-thru experience. "Wendy's is such a great partner, we had to continue our cosmic journey with them," said Tricia Melton, CMO of Warner Bros. Global Kids, Young Adults and Classics. "Thanks to them and Coca-Cola, fans can celebrate Rick and Morty Day with a Portal Time Lemon Lime in one hand and a BerryJerryboree in the other. And to quote the wise Rick Sanchez from season 4, we looked right into the bleeding jaws of capitalism and said, yes daddy please." "We're big fans of Rick and Morty and continuing another season with our partnership with entertainment 1 powerhouse Adult Swim," said Carl Loredo, Chief Marketing Ocer for the Wendy's Company. "We love nding authentic ways to connect with this passionate fanbase and are excited to extend the Rick and Morty experience into our menu, incredible content and great delivery deals all season long." Thanks to the innovative team at Coca-Cola, fans will be able to sip on two new avor mixes created especially for the series starting on Wednesday, June 16 at more than 5,000 Wendy's locations through August 22, the date of the Rick and Morty season ve nale. -

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 14 (Spring 2020) Warsaw 2020 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Justyna Fruzińska, Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Łukasz Muniowski, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Ewa Antoszek, Edyta Frelik, Elżbieta Klimek-Dominiak, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Tadeusz Pióro, Elżbieta Rokosz-Piejko, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Stefan Schubert, Joanna Ziarkowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Vegas Options” from the series “Las Vegas.” By permission. www.flickr/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733-9154 eISSN 2544-8781 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02-653 Warsaw paas.org.pl Nakład 110 egz. Wersją pierwotną Czasopisma jest wersja drukowana. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents ARTICLES Justyna Włodarczyk Beyond Bizarre: Nature, Culture and the Spectacular Failure of B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Missiles .......................................................................... 5 Małgorzata Olsza Feminist (and/as) Alternative Media Practices in Women’s Underground Comix in the 1970s ................................................................ 19 Arkadiusz Misztal Dream Time, Modality, and Counterfactual Imagination in Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon ............................................................................... 37 Ewelina Bańka Walking with the Invisible: The Politics of Border Crossing in Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway: A True Story ............................................. -

List of Discussion Titles (By Title)

The “Booked for the Evening” book discussion group began March 1999. Our selections have included fiction, mysteries, science fiction, short stories, biographies, non-fiction, memoirs, historical fiction, and young adult books. We’ve been to Europe, Asia, the Middle East, South America, the Antarctic, Africa, India, Australia, Canada, Mexico, and the oceans of the world. We’ve explored both the past and the future. After more than 15 years and over two hundred books, we are still reading, discussing, laughing, disagreeing, and sharing our favorite titles and authors. Please join us for more interesting and lively book discussions. For more information contact the Roseville Public Library 586-445-5407. List of Discussion Titles (by title) 1984 George Orwell February 2014 84 Charring Cross Road Helene Hanff November 2003 A Cold Day in Paradise Steve Hamilton October 2008 A Patchwork Planet Anne Tyler July 2001 A Prayer for Owen Meany John Irving December 1999 A Room of One’s Own Virginia Wolff January 2001 A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian Marina Lewycka December 2008 The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian Sherman Alexie October 2010 Affliction Russell Banks August 2011 The Alchemist Paulo Coelho June 2008 Along Came a Spider James Patterson June 1999 An Inconvenient Wife Megan Chance April 2007 Anatomy of a Murder Robert Traver November 2006 Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt August 1999 Angle of Repose Wallace Stegner April 2010 Annie's Ghosts: A Journey into a Family Secret Steve Luxenberg October 2013 Arc of Justice: a Saga of Race, Civil Rights and Murder in the Jazz Age Kevin Boyle February 2007 Around the World in Eighty Days Jules Verne July 2011 Page 1 of 6 As I Lay Dying William Faulkner July 1999 The Awakening Kate Chopin November 2001 Ballad of Frankie Silver Sharyn McCrumb June 2003 Before I Go to Sleep S. -

Kristen Connolly Helps Move 'Zoo' Far Ahead

Looking for a way to keep up with local news, school happenings, sports events and more? 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad We’ve got you covered! June 23 - 29, 2017 waxahachietx.com U J A M J W C Q U W E V V A H 2 x 3" ad N A B W E A U R E U N I T E D Your Key E P R I D I C Z J Z A Z X C O To Buying Z J A T V E Z K A J O D W O K W K H Z P E S I S P I J A N X and Selling! 2 x 3.5" ad A C A U K U D T Y O W U P N Y W P M R L W O O R P N A K O J F O U Q J A S P J U C L U L A Co-star Kristen Connolly L B L A E D D O Z L C W P L T returns as the third L Y C K I O J A W A H T O Y I season of “Zoo” starts J A S R K T R B R T E P I Z O Thursday on CBS. O N B M I T C H P I G Y N O W A Y P W L A M J M O E S T P N H A N O Z I E A H N W L Y U J I Z U P U Y J K Z T L J A N E “Zoo” on CBS (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Jackson (Oz) (James) Wolk Hybrids Place your classified Solution on page 13 Jamie (Campbell) (Kristen) Connolly (Human) Population ad in the Waxahachie Daily 2 x 3" ad Mitch (Morgan) (Billy) Burke Reunited Light, Midlothian1 xMirror 4" ad and Abraham (Kenyatta) (Nonso) Anozie Destruction Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search Dariela (Marzan) (Alyssa) Diaz (Tipping) Point Kristen Connolly helps Call (972) 937-3310 © Zap2it move ‘Zoo’ far ahead 2 x 3.5" ad 2 x 4" ad 4 x 4" ad 6 x 3" ad 16 Waxahachie Daily Light Cardinals. -

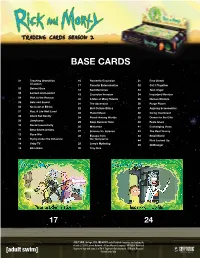

Rick and Morty Season 2 Checklist

TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 BASE CARDS 01 Teaching Grandkids 16 Romantic Excursion 31 Emo Streak A Lesson 17 Parasite Extermination 32 Get It Together 02 Behind Bars 18 Bad Memories 33 Teen Angst 03 Locked and Loaded 19 Cromulon Invasion 34 Important Member 04 Rick to the Rescue 20 A Man of Many Talents 35 Human Wisdom 05 Safe and Sound 21 The Ascension 36 Purge Planet 06 No Code of Ethics 22 Bird Culture Ethics 37 Aspiring Screenwriter 07 Roy: A Life Well Lived 23 Planet Music 38 Going Overboard 08 Silent But Deadly 24 Peace Among Worlds 39 Dinner for the Elite 09 Jerryboree 25 Keep Summer Safe 40 Feels Good 10 Racial Insensitivity 26 Miniverse 41 Exchanging Vows 11 Beta-Seven Arrives 27 Science Vs. Science 42 The Real Tammy 12 Race War 28 Escape from 43 Small World 13 Flying Under the Influence the Teenyverse 44 Rick Locked Up 14 Unity TV 29 Jerry’s Mytholog 45 Cliffhanger 15 Blim Blam 30 Tiny Rick 17 24 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. A Time Warner Company. All Rights Reserved. Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. Printed in the USA. TRADING CARDS SEASON 2 CHARACTERS chase cards (1:3 packs) C1 Unity C7 Mr. Poopybutthole C2 Birdperson C8 Fourth-Dimensional Being C3 Krombopulos Michael C9 Zeep Xanflorp C4 Fart C10 Arthricia C5 Ice-T C11 Glaxo Slimslom C6 Tammy Gueterman C12 Revolio Clockberg Jr. C1 C3 C9 ADULT SWIM, the logo, RICK AND MORTY and all related characters are trademarks of and © 2019 Cartoon Network. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

Theanti Antidepressant

AUGUST 7, 2017 THE ANTI ANTIDEPRESSANT Depression afflicts 16 million Americans. One-third don’t respond to treatment. A surprising new drug may change that BY MANDY OAKLANDER time.com VOL. 190, NO. 6 | 2017 5 | Conversation Time Off 6 | For the Record What to watch, read, The Brief see and do News from the U.S. and 51 | Television: around the world Jessica Biel is The Sinner; 7 | A White House Kylie Jenner’s new gone haywire reality show 10 | A cold war takes 53 | What makes hold with Qatar Rick and Morty so fun 14 | A free medical clinic in Appalachia 56 | Studying the draws thousands racism in classic children’s books 16 | Ian Bremmer on the erosion of 59 | Kristin liberal democracy van Ogtrop on in Europe parenting in an age of anxiety 18 | Protests in Jerusalem’s Old City 60 | 7 Questions for nonverbal autistic writer Naoki Higashida The View Ideas, opinion, innovations 21 | A cancer survivor on society’s unrealistic expectations for coping with the diagnosis ◁ Laurie Holt at 25 | How climate a rally on July 7 change became in Riverton, political Utah, to raise The Features awareness for her son Joshua, who 26 | Mon dieu! New Hope The Anti Blonde Ambition is imprisoned in Notre Dame’s cash Venezuela crisis pits the church for American Antidepressant As an undercover spy in against the state Photograph by Captives A controversial new Atomic Blonde, Charlize Michael Friberg for TIME 28 | James Stavridis Inside the effort to drug could help treat the Theron is pushing the offers six ways to bring home Americans millions of Americans boundaries of female-led ease Europe’s fears imprisoned abroad afflicted by depression action films about the Trump- By Mandy Oaklander38 By Eliana Dockterman46 Putin relationship By Elizabeth Dias30 ON THE COVER: Photo-illustration by Michael Marcelle TIME (ISSN 0040-781X) is published by Time Inc.