Open Space Master Plan for Louisville Owned Parcels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Response of Selected Plants to Fire on White Sands

Session D—Ecology of Fire on White Sands Missile Range—Boykin Response of Selected Plants to Fire on 1 White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico 2 Kenneth G. Boykin Abstract Little was known about the ecology, impacts, effects, and history of fire related to many plants and communities within White Sands Missile Range. I began by identifying the known aspects and the gaps in knowledge for White Sands Missile Range. I analyzed existing data available for the Installation taken from the Integrated Training and Area Management (ITAM) program for 1988 to 1999. Burn plots were identified at 34 sites with fires occurring sometime within that 11 yr span. Selected plant species were analyzed to identify the response to fire including change in frequency, cover, and structure. Analysis of data indicated varied responses to fire and identified a need for long term monitoring to account for natural variability. Introduction Fire is a major factor influencing the ecology, evolution, and biogeography of many vegetation communities (Humphrey 1974, Ford and McPherson 1996). In the Southwest, semi-desert grasslands and shrublands have evolved with fires caused by lightning strikes (Pyne 1982, Betancourt and others 1990). Fires have maintained grasslands by reducing invading shrubs (Valentine 1971). The impact these fires have on the ecosystem depends not only on current biological and physical environment but also on past land use patterns (Ford and McPherson 1996). Fires impact communities by affecting species diversity, persistence, opportunistic invading species, insects, diseases, and herbivores. Plant species diversity often increases after fires and some communities are dependent on fire to maintain their structure (Jacoby 1998). -

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea Grossulariifolia (Hook

GOOSEBERRYLEAF GLOBEMALLOW Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Rydb. Malvaceae – Mallow family Corey L. Gucker & Nancy L. Shaw | 2018 ORGANIZATION NOMENCLATURE Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Names, subtaxa, chromosome number(s), hybridization. Rydb., hereafter referred to as gooseberryleaf globemallow, belongs to the Malveae tribe of the Malvaceae or mallow family (Kearney 1935; La Duke 2016). Range, habitat, plant associations, elevation, soils. NRCS Plant Code. SPGR2 (USDA NRCS 2017). Subtaxa. The Flora of North America (La Duke 2016) does not recognize any varieties or Life form, morphology, distinguishing characteristics, reproduction. subspecies. Synonyms. Malvastrum coccineum (Nuttall) A. Gray var. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) Growth rate, successional status, disturbance ecology, importance to animals/people. Torrey, M. grossulariifolium (Hooker & Arnott) A. Gray, Sida grossulariifolia Hooker & Arnott, Sphaeralcea grossulariifolia subsp. pedata Current or potential uses in restoration. (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. grossulariifolia var. pedata (Torrey ex A. Gray) Kearney, S. pedata Torrey ex A. Gray (La Duke 2016). Seed sourcing, wildland seed collection, seed cleaning, storage, Common Names. Gooseberryleaf globemallow, testing and marketing standards. current-leaf globemallow (La Duke 2016). Chromosome Number. Chromosome number is stable, 2n = 20, and plants are diploid (La Duke Recommendations/guidelines for producing seed. 2016). Hybridization. Hybridization occurs within the Sphaeralcea genus. -

A Reciprocal Transplant Experiment with Winterfat (Krascheninnikovia Lanata) Melanie Barnes

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-1-2009 The effect of plant source location on restoration success: a reciprocal transplant experiment with winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata) Melanie Barnes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Recommended Citation Barnes, Melanie. "The effect of plant source location on restoration success: a reciprocal transplant experiment with winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata)." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/4 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The effect of plant source location on restoration success: a reciprocal transplant experiment with winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata) BY Melanie G. Barnes B.A., Biology, Reed College, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December, 2009 DEDICATION In memory of my mother, Georgene Grace Barnes. The completion of this dissertation is also dedicated to my friends and family who have supported me in this endeavor and who taught me many things about life that gave me the perspective I needed to complete this work. I would like to thank Heather Simpson, Jerusha Reynolds, Terri Koontz, Nathan Abrahamson, Jeremy Barlow, Brittany Barker, Laura Calabrese, Jennifer Hollis, Maureen Peters, Helen Barnes, and Tom Barnes. Finally, I want to thank Lisa for her love and emotional support; it means the world to me. -

Food Habits of Rodents Inhabiting Arid and Semi-Arid Ecosystems of Central New Mexico." (2007)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Special Publications Museum of Southwestern Biology 5-10-2007 Food Habits of Rodents Inhabiting Arid and Semi- arid Ecosystems of Central New Mexico Andrew G. Hope Robert R. Parmenter Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/msb_special_publications Recommended Citation Hope, Andrew G. and Robert R. Parmenter. "Food Habits of Rodents Inhabiting Arid and Semi-arid Ecosystems of Central New Mexico." (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/msb_special_publications/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum of Southwestern Biology at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Publications by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE MUSEUM OF SOUTHWESTERN BIOLOGY NUMBER 9, pp. 1–75 10 May 2007 Food Habits of Rodents Inhabiting Arid and Semi-arid Ecosystems of Central New Mexico ANDREW G. HOPE AND ROBERT R. PARMENTER1 Special Publication of the Museum of Southwestern Biology 1 CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Study Sites .......................................................................................................................................... -

Winterfat Tested Class of Natural Germplasm

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE BRIDGER, MONTANA and MONTANA AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION BOZEMAN, MONTANA and WYOMING AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION LARAMIE, WYOMING NOTICE OF RELEASE OF OPEN RANGE WINTERFAT TESTED CLASS OF NATURAL GERMPLASM The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Montana and Wyoming Agricultural Experiment Stations announce the release of a ‘Tested Class Germplasm’ of winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata [Pursh] Guldenstaedt, syn. Ceratoides lanata [Pursh] J.T. Howell, syn. Eurotia lanata [Pursh] Moq.), a low growing, shrub, native to the northern Great Plains and Intermountain Desertic Basin. Winterfat has also been referred to as whitesage, lambstail, or sweetsage. This release was evaluated and selected by the USDA-NRCS Plant Materials Center (PMC) at Bridger, Montana. Collection Site Information: Open Range Tested Class Germplasm of winterfat is a composite of three accessions: 9039363 collected near Terry, Montana (Custer County), by D. Grandbois (1985), 9039365 collected near Bridger, Montana (Carbon County), by B. Thompson (1985), and 9039416 collected near Rawlins, Wyoming (Carbon County), by R. Baumgartner (1985). Description: The Open Range release is typical of the species, having the same general morphological and physiological characteristics. Winterfat is a half-shrub measuring 0.3 to 0.75 meters (1.0 to 2.5 ft.) tall. From a woody base, the plants produce numerous erect, annual branches. The stems and leaves are covered with soft, woolly hairs that give the plants a whitish to gray-green appearance. The sessile to short-petioled, lanceolate leaves have enrolled edges and persist through the winter season. The plants are monoecious. -

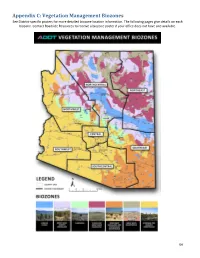

Appendix C: Vegetation Management Biozones See District-Specific Posters for More Detailed Biozone Location Information

Appendix C: Vegetation Management Biozones See District-specific posters for more detailed biozone location information. The following pages give details on each biozone. Contact Roadside Resources to receive a biozone poster if your office does not have one available. 59 CONIFER FOREST • Needleleaf evergreen trees dominate in this biozone • Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) is the most common tree species, occurring at the lower elevations • Occasionally found at the lower elevations are the deciduous trees Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii) and New Mexico locust (Robinia neomexicana). • The most common mid- elevation conifer is Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). • Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii) and other spruces are found at the higher elevations of the conifer forest. Temperature • Quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides) fills a 100 niche role in vegetational succession, appearing after fire or other forest 80 disturbance 60 Average Maximum Temperature (F) • Shrubs, grasses, and forbs are not common 40 in the understory, but may occur in natural Average Minimum Temperature (F) openings and at the edge of the forest 20 Freezing (F) • Mountain slopes, high plateaus, as well as 0 canyons, support conifer forest vegetation Jan Oct Apr Feb July Dec Aug Nov Mar May Sept • Soils found within this biozone include June Month andesite, basalt, granite, limestone, and Precipitation sandstone 25 • Elevations range from 3,900 to 8,300 feet • Summer precipitation (July, August, 20 Average Total September) accounts for nearly half of the Precipitation -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Cushion-Plant Vegetation on Public Lands in the Blm Rock Springs Field Office, Wyoming

CUSHION-PLANT VEGETATION ON PUBLIC LANDS IN THE BLM ROCK SPRINGS FIELD OFFICE, WYOMING Final Report for Assistance Agreement KAA010012, Task Order No. TO-13 between the BLM Rock Springs Field Office, and the University of Wyoming, Wyoming Natural Diversity Database By George P. Jones Wyoming Natural Diversity Database, University of Wyoming Laramie, Wyoming October 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Methods ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Sample Area Selection ................................................................................................................ 3 Data Collection ............................................................................................................................ 4 Data Analysis .............................................................................................................................. 5 Results ............................................................................................................................................. 7 -

TAXONOMY Plant Family Species Scientific Name GENERAL

Plant Propagation Protocol for Krascheninnikovia lanata ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production Protocol URL: https://courses.washington.edu/esrm412/protocols/KRLA2.pdf TAXONOMY Plant Family Scientific Name Amaranthaceae Common Name Amaranth family Species Scientific Name Scientific Name Krascheninnikovia lanata (Pursh) A. Meeuse & Smit Varieties None Sub-species None Cultivar None Common Synonym(s) Ceratoides lanata (Pursh) J.T. Howell, invalid (Jeps) Diotis lanata Pursh Eurotia lanata (Pursh) Moq., invalid Eurotia lanata (Pursh) Moq. var. subspinosa (Rydberg) Kearney & Peebles Common Name(s) Winterfat, white sage, winter-sage, feather-sage, sweet sage, lambstail Species Code (as per USDA Plants KRLA2 database) GENERAL INFORMATION1,2,3,4 Geographical range Distribution maps from the USDA Plants Database. Ecological distribution Krascheninnikovia lanata occurs in the plains and foothills of western North America. It is often found in saline or alkaline soil. This species is not tolerant to floods or acidic soil. Climate and elevation range Krascheninnikovia lanata grows in arid climates from sea level up to 10,000 feet elevation. Local habitat and abundance This species grows east of the Cascades in southern parts of Washington. Plant strategy type / successional This plant is a drought-tolerant, frost-tolerant perennial stage shrub. It also tolerates saline and/or alkaline soils. Plant characteristics − A wooly, spreading shrub with a woody base up to 2 dm. tall and annual stems up to 5 dm. long. − Flowers are wooly and non-showy. They bloom from May to July in clusters on the leaf axils. − Leaves are numerous, linear, and pubescent; up to 4 cm. long. − The root system is extensive and fibrous with a deep taproot. -

Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact for Herbicide Use Within Authorized Power Line Rights-Of-Way on National Forest System Lands in Arizona

United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Assessment and Finding of No Significant Impact for Herbicide Use within Authorized Power Line Rights-of-Way on National Forest System Lands in Arizona Forest Service Southwestern Region Apache-Sitgreaves, Coconino, Kaibab, Prescott, and Tonto National Forests December 2018 Page intentionally left blank For More Information Contact: Thomas Torres, P.E. Deputy Forest Supervisor Tonto National Forest 2324 East McDowell Road Phoenix, Arizona 85006 Phone: 602.225.5203 Email: [email protected] In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

An Illustrated Key to the Amaranthaceae of Alberta

AN ILLUSTRATED KEY TO THE AMARANTHACEAE OF ALBERTA Compiled and writen by Lorna Allen & Linda Kershaw April 2019 © Linda J. Kershaw & Lorna Allen This key was compiled using informaton primarily from Moss (1983), Douglas et. al. (1998a [Amaranthaceae], 1998b [Chenopodiaceae]) and the Flora North America Associaton (2008). Taxonomy follows VASCAN (Brouillet, 2015). Please let us know if there are ways in which the key can be improved. The 2015 S-ranks of rare species (S1; S1S2; S2; S2S3; SU, according to ACIMS, 2015) are noted in superscript (S1;S2;SU) afer the species names. For more details go to the ACIMS web site. Similarly, exotc species are followed by a superscript X, XX if noxious and XXX if prohibited noxious (X; XX; XXX) according to the Alberta Weed Control Act (2016). AMARANTHACEAE Amaranth Family [includes Chenopodiaceae] Key to Genera 01a Flowers with spiny, dry, thin and translucent 1a (not green) bracts at the base; tepals dry, thin and translucent; separate ♂ and ♀ fowers on same the plant; annual herbs; fruits thin-walled (utricles), splitting open around the middle 2a (circumscissile) .............Amaranthus 01b Flowers without spiny, dry, thin, translucent bracts; tepals herbaceous or feshy, greenish; fowers various; annual or perennial, herbs or shrubs; fruits various, not splitting open around the middle ..........................02 02a Leaves scale-like, paired (opposite); stems feshy/succulent, with fowers sunk into stem; plants of saline habitats ... Salicornia rubra 3a ................. [Salicornia europaea] 02b Leaves well developed, not scale-like; stems not feshy; plants of various habitats. .03 03a Flower bracts tipped with spine or spine-like bristle; leaves spine-tipped, linear to awl- 5a shaped, usually not feshy; tepals winged from the lower surface .............. -

Towards a Species Level Tree of the Globally Diverse Genus

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 62 (2012) 359–374 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Towards a species level tree of the globally diverse genus Chenopodium (Chenopodiaceae) ⇑ Susy Fuentes-Bazan a,b, Guilhem Mansion a, Thomas Borsch a, a Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin-Dahlem und Institut für Biologie, Freie Universität Berlin, Dahlem Centre of Plant Sciences, Königin-Luise-Straße 6-8, 14195 Berlin, Germany b Herbario Nacional de Bolivia, Universidad Mayor de San Andrés (UMSA), La Paz, Bolivia article info abstract Article history: Chenopodium is a large and morphologically variable genus of annual and perennial herbs with an almost Received 21 March 2011 global distribution. All subgenera and most sections of Chenopodium were sampled along with other gen- Revised 28 September 2011 era of Chenopodieae, Atripliceae and Axyrideae across the subfamily Chenopodioideae (Chenopodiaceae), Accepted 11 October 2011 totalling to 140 taxa. Using Maximum parsimony and Bayesian analyses of the non-coding trnL-F Available online 24 October 2011 (cpDNA) and nuclear ITS regions, we provide a comprehensive picture of relationships of Chenopodium sensu lato. The genus as broadly classified is highly paraphyletic within Chenopodioideae, consisting of Keywords: five major clades. Compared to previous studies, the tribe Dysphanieae with three genera Dysphania, Tel- Chenopodium oxys and Suckleya (comprising the aromatic species of Chenopodium s.l.) is now shown to form one of the Chenopodioideae Chenopodieae early branches in the tree of Chenopodioideae. We further recognize the tribe Spinacieae to include Spina- TrnL-F cia, several species of Chenopodium, and the genera Monolepis and Scleroblitum.