What We Can Learn from Bobby Fischer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999/6 Layout

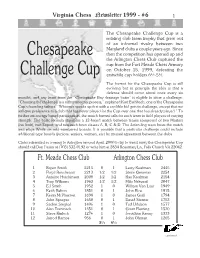

Virginia Chess Newsletter 1999 - #6 1 The Chesapeake Challenge Cup is a rotating club team trophy that grew out of an informal rivalry between two Maryland clubs a couple years ago. Since Chesapeake then the competition has opened up and the Arlington Chess Club captured the cup from the Fort Meade Chess Armory on October 15, 1999, defeating the 1 1 Challenge Cup erstwhile cup holders 6 ⁄2-5 ⁄2. The format for the Chesapeake Cup is still evolving but in principle the idea is that a defense should occur about once every six months, and any team from the “Chesapeake Bay drainage basin” is eligible to issue a challenge. “Choosing the challenger is a rather informal process,” explained Kurt Eschbach, one of the Chesapeake Cup's founding fathers. “Whoever speaks up first with a credible bid gets to challenge, except that we will give preference to a club that has never played for the Cup over one that has already played.” To further encourage broad participation, the match format calls for each team to field players of varying strength. The basic formula stipulates a 12-board match between teams composed of two Masters (no limit), two Expert, and two each from classes A, B, C & D. The defending team hosts the match and plays White on odd-numbered boards. It is possible that a particular challenge could include additional type boards (juniors, seniors, women, etc) by mutual agreement between the clubs. Clubs interested in coming to Arlington around April, 2000 to try to wrest away the Chesapeake Cup should call Dan Fuson at (703) 532-0192 or write him at 2834 Rosemary Ln, Falls Church VA 22042. -

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

Social Conflict and Sacrificial Rhetoric

CHRISTOPHER ROBERTS Social Conflict and Sacrificial Rhetoric Luther’s Discursive Intervention and the Religious Division of Labor Introduction ‘Sacrifice’ is a religious term whose use extends far beyond the church door. People from all walks of life speak of ‘sacrifice’ when they want to evoke an irreducible conflict in the relations between self, family, and soci- ety. In America, hardly a speech goes by without political leaders insisting upon the necessity and virtue of sacrifice, but rarely will they clarify who is sacrificing what, and to whom. Indeed, this is not only an American phenomenon, as a number of recent texts examining ‘sacrifice’ as a term in various national discourses have shown.1 Such a political and economic deployment of a religious figure demands interpretation, for not only does the rhetoric of sacrifice span the globe,2 it constitutes a problem with a long genealogy. As a key moment in the Western segment of this genealogy, this article will examine the way that Luther’s exegetical work rhetoricalized sacrifice, and, in doing so, constructed a new discursive position, the pas- tor as anti-sophist, or parrhesiast, in the religious division of labor. The overarching question for this inquiry is how did a particular re- ligious ritual like sacrifice come to serve as such a widespread rhetorical figure? When faced with the immense historical distance between, first, the public destruction of wealth or butchering of an animal, and, last, a speech act describing non-ritual phenomena as a sacrifice, one measures the distance not only in years but also in religious and cultural transform- ation. -

CONTENTS Contents

CONTENTS Contents Symbols 5 Preface 6 Introduction 9 1 Glossary of Attacking and Strategic Terms 11 2 Double Attack 23 2.1: Double Attacks with Queens and Rooks 24 2.2: Bishop Forks 31 2.3: Knight Forks 34 2.4: The Í+Ì Connection 44 2.5: Pawn Forks 45 2.6: The Discovered Double Attack 46 2.7: Another Type of Double Attack 53 Exercises 55 Solutions 61 3 The Role of the Pawns 65 3.1: Pawn Promotion 65 3.2: The Far-Advanced Passed Pawn 71 3.3: Connected Passed Pawns 85 3.4: The Pawn-Wedge 89 3.5: Passive Sacrifices 91 3.6: The Kamikaze Pawn 92 Exercises 99 Solutions 103 4 Attacking the Castled Position 106 4.1: Weakness in the Castled Position 106 4.2: Rooks and Files 112 4.3: The Greek Gift 128 4.4: Other Bishop Sacrifices 133 4.5: Panic on the Long Diagonal 143 4.6: The Knight Sacrifice 150 4.7: The Exchange Sacrifice 162 4.8: The Queen Sacrifice 172 Exercises 176 Solutions 181 5 Drawing Combinations 186 5.1: Perpetual Check 186 5.2: Repetition of Position 194 5.3: Stalemate 197 5.4: Fortress and Blockade 202 5.5: Positional Draws 204 Exercises 207 Solutions 210 6 Combined Tactical Themes 213 6.1: Material, Endings, Zugzwang 214 6.2: One Sacrifice after Another 232 6.3: Extraordinary Combinations 242 6.4: A Diabolical Position 257 Exercises 260 Solutions 264 7 Opening Disasters 268 7.1: Open Games 268 7.2: Semi-Open Games 274 7.3: Closed Games 288 8 Tactical Examination 304 Test 1 306 Test 2 308 Test 3 310 Test 4 312 Test 5 314 Test 6 316 Hints 318 Solutions 320 Index of Names 331 Index of Openings 335 THE ROLE OF THE PAWNS 3 The Role of the Pawns Ever since the distant days of the 18th century 3.1: Pawn Promotion (let us call it the time of the French Revolution, or of François-André Danican Philidor) we have known that “pawns are the soul of chess”. -

UIL Text 111212

UIL Chess Puzzle Solvin g— Fall/Winter District 2016-2017 —Grades 4 and 5 IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: [Test-administrators, please read text in this box aloud.] This is the UIL Chess Puzzle Solving Fall/Winter District Test for grades four and five. There are 20 questions on this test. You have 30 minutes to complete it. All questions are multiple choice. Use the answer sheet to mark your answers. Multiple choice answers pur - posely do not indicate check, checkmate, or e.p. symbols. You will be awarded one point for each correct answer. No deductions will be made for incorrect answers on this test. Finishing early is not rewarded, even to break ties. So use all of your time. Some of the questions may be hard, but all of the puzzles are interesting! Good luck and have fun! If you don’t already know chess notation, reading and referring to the section below on this page will help you. How to read and answer questions on this test Piece Names Each chessman can • To answer the questions on this test, you’ll also be represented need to know how to read chess moves. It’s by a symbol, except for the pawn. simple to do. (Figurine Notation) K King Q • Every square on the board has an “address” Queen R made up of a letter and a number. Rook B Bishop N Knight Pawn a-h (We write the file it’s on.) • To make them easy to read, the questions on this test use the figurine piece symbols on the right, above. -

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

A Glimpse Into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015

Media Contact: Amanda Cook [email protected] 314-598-0544 A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer July 24, 2014 – June 7, 2015 July XX, 2014 (Saint Louis, MO) – From his earliest years as a child prodigy to becoming the only player ever to achieve a perfect score in the U.S. Chess Championships, from winning the World Championship in 1972 against Boris Spassky to living out a controversial retirement, Bobby Fischer stands as one of chess’s most complicated and compelling figures. A Memorable Life: A Glimpse into the Complex Mind of Bobby Fischer opens July 24, 2014, at the World Chess Hall of Fame (WCHOF) and will celebrate Fischer’s incredible career while examining his singular intellect. The show runs through June 7, 2015. “We are thrilled to showcase many never-before-seen artifacts that capture Fischer’s career in a unique way. Those who study chess will have the rare opportunity to learn from his notes and books while casual fans will enjoy exploring this superstar’s personal story,” said WCHOF Chief Curator Bobby Fischer, seen from above, Shannon Bailey. makes a move during the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup. Several of the rarest pieces on display are on generous loan from Dr. Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield, owners of a a collection of material from Fischer’s own library that includes 320 books and 400 periodicals. These items supplement highlights from WCHOF’s permanent collection to create a spectacular show. Highlights from the exhibition: Furniture from the home of Fischer’s mentor Jack Collins, which -

NEW HAMPSHIRE CHESS JOURNAL Is a Publication of the New Hampshire Chess Association

New Hampshire Chess Journal December 2013 Volume 2013 No. 1 Return of the King: Sharif Khater Story, Page 2 Khater Returns as 2013 NH Amateur Champ Manchester--Sherif Khater recaptured the State Amateur crown, which he first held in 2010, by beating Arthur Tang in the final round of the 38th New Hampshire Amateur Championship, held at the Comfort Inn in Manchester on November 2. Only a second round draw with Brian Bambrough blemished Khater’s score. Four tied for second place: Gerald Potorski, Jefferey Ames, Clay Bradley, and Joshua Cote. John Jay Naylor won the Intermediate section with a perfect 4.0 score. Thomas Allen of Maine scored a perfect 4.0 for first place in the Novice section. Sixty-four players competed in the four round, one day event. Hal Terrie directed with the assistance of John Elmore. The crosstable can be viewed here. Bournival NH Open State Champ Manchester—Brad Bournival was named the 2013 NH State Champion at the 63rd New Hampshire Open. GM Alexander Ivanov and Jonathan Yedidia, both of Massachusetts, shared first place. Yedidia caught Ivanov in the final round by beating Brian Salomon while Ivanov drew with state champ Brad Bournival, leaving the leaders with 4.0 points each. Bournival took third place. John Pythyon, Sr. of Maine won the under 1950 section, while Paul Kolojeski Alexander Ivanov and Brian Salomon square off in Round 4. Ivanov won. 2 prevailed in the Under 1650 section. The Open drew 37 participants to the Manchester Comfort in on June 14-16. The tournament was directed by Hal Terrie with John Elmore assisting. -

CHESS INFORMANT Contain

Drawing by Bob Brandreth , The , E"..-y ail: mono. the Yuqoalav ChI .. Federation brings out a Dew book of the tin.. 1 gom.. plared dwinq the preceding baH y.ar. A unique. Dewly-deviled aystem of annotating gwu_ by coded ligna moida all languuge obetcd... 1'Ju. malt. possible a univeraally usable and yet V'Osonably-priced book which brings the neweat ideaa in the opening,; and throughout the game to every ch.. enthusiast more quickly U"m ever before. Book 6 confaina 821 gam.. played between July 1 and D.cember 31, 1968. A qreat aelectiOD of theoretically important gam_ from 28 toumcnrumta and match.. , inc1uding the Lugano Olympiad. World Student Team Cbmnpionsbip (Ybb.), Mar del Plata. Netanya, Amaterdam. Skopje, Debrecen, Sombot. Havana. Vinkovci, Belgrade, Palma d. Majorca, and Athens, S.pacial New Featurel Beginning with Book 6. each CHESS INFORMANT contain. a aection for FIDE communicati0D8, re placing the former official publication FIDE REVIEW. The FIDE section in this iau. contains comple'e Regu1ationa for the Toumamenta and Match BII for the Men'. and l.cdl·,' World CbampiC'Dlhipa. Pr.. crih n the entire competition .,atem from Zonal cmd Interzonal Toummnenta throuqb the Ccmdidatea Matches to the World Championship Match. Book 6 has aections leaturing 51 brilliant Combinations and 45 Endings from actual play during the preceding six months. Another interesting feature ia a table listing in Older the Ten Beat Gam,ea from Book 5 and showing how each of the eight Grandmastem on the jury voted. Contains an Engliah·lanquage introduction. esplanation of the annotation cod•• indez of play em and comm._tcrton. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

David Bronstein

The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein Genna Sosonko The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein Author: Genna Sosonko Managing Editor: Ilan Rubin, Founder and CEO, LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House (www.elkandruby.ru) Translated from the Russian by Ilan Rubin Edited by Reilly Costigan-Humes Typesetting by Andrei Elkov (www.elkov.ru) Artwork by Sergey Elkin First published in Russia in 2014 © LLC Elk and Ruby Publishing House, 2017 (English version). All rights reserved © Genna Sosonko and Andrei Elkov, 2014 (Russian original). All rights reserved ISBN 978-5-9500433-1-4 Foreword by Garry Kasparov David Bronstein – Chess Innovator It gives me immense pleasure to introduce the first English edition of Genna Sosonko’s book The Rise and Fall of David Bronstein, a work devoted to the life and times of a brilliant grandmaster who was just a step away from reaching the very summit of Mount Olympus, and who, in terms of his understanding of the game, undoubtedly belonged to the world champions’ club. Bronstein’s games were full of original, fresh solutions and exciting, amazing ideas nobody had ever come up with before. He possessed a unique vision of the chess board and was irresistibly drawn to unconventionality. Sometimes, ingenious concepts were hidden behind this unconventionality, ones that proved to be way ahead of their time. Bronstein stands out from post-war generation grandmasters in terms of the sheer volume of his contribution to chess. He was one of the game’s greatest popularizers. Take his famous book Zurich International Chess Tournament (1953), for instance: he wrote a truly iconic middle-game textbook based on the analysis of that super-tournament’s games that proved to be useful even for average players. -

Ocm-2019-12-01

1 DECEMBER 2019 Chess News and Chess History for Oklahoma Howard Zhong and Frank K. Berry Editor’s Note – Enjoy this Thanksgiving Remembrance of Frank Berry by Cheng Zhong, father of NM Howard Zhong. It focuses on his help to Cheng with the responsibilities of being a “Chess Dad” for a talented youngster, and gives insight into the type of ‘mover and In This Issue: shaker’ Frank was, and how he is still missed. • Frank Berry Remembrance • An Okie Chess Giant “Oklahoma’s Official Chess FKB’s Archives In Memory of Frank Berry from a Bulletin Covering Oklahoma Chess • Chess Parent’s Perspective on a Regular Schedule Since 1982” 2019 OKC by Cheng Zhong Open http://ocfchess.org • Thanksgiving is a time for remembrance and Oklahoma Chess IM Donaldson appreciation. Although Frank Berry, the Foundation Reviews Oklahoma Chess giant, has left us for more than Register Online for Free • three years, I cannot forget his role in my son Editor: Tom Braunlich Plus Howard’s chess development and many things Asst. Ed. Rebecca Rutledge News Bites, he did for us. Published the 1st of each month. Game of the Month, Exactly eight years ago, after an excellent Send story submissions and Puzzles, performance at the 2011 National K-12 Grade tournament reports, etc., by the Top 25 List, Championships, Howard wanted my wife 15th of the previous month to Tournament Jianming and me to take him to Stillwater for mailto:[email protected] Reports, an OCF tournament after Thanksgiving. Prior and more. to that, I had never been to an OCF chess ©2019 All rights reserved.