ABSTRACT PRETEND This Is a Collection of Short Stories That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music & Film Memorabilia

MUSIC & FILM MEMORABILIA Friday 11th September at 4pm On View Thursday 10th September 10am-7pm and from 9am on the morning of the sale Catalogue web site: WWW.LSK.CO.Uk Results available online approximately one hour following the sale Buyer’s Premium charged on all lots at 20% plus VAT Live bidding available through our website (3% plus VAT surcharge applies) Your contact at the saleroom is: Glenn Pearl [email protected] 01284 748 625 Image this page: 673 Chartered Surveyors Glenn Pearl – Music & Film Memorabilia specialist 01284 748 625 Land & Estate Agents Tel: Email: [email protected] 150 YEARS est. 1869 Auctioneers & Valuers www.lsk.co.uk C The first 91 lots of the auction are from the 506 collection of Jonathan Ruffle, a British Del Amitri, a presentation gold disc for the album writer, director and producer, who has Waking Hours, with photograph of the band and made TV and radio programmes for the plaque below “Presented to Jonathan Ruffle to BBC, ITV, and Channel 4. During his time as recognise sales in the United Kingdom of more a producer of the Radio 1 show from the than 100,000 copies of the A & M album mid-1980s-90s he collected the majority of “Waking Hours” 1990”, framed and glazed, 52 x 42cm. the lots on offer here. These include rare £50-80 vinyl, acetates, and Factory Records promotional items. The majority of the 507 vinyl lots being offered for sale in Mint or Aerosmith, a presentation CD for the album Get Near-Mint condition – with some having a Grip with plaque below “Presented to Jonathan never been played. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

Hawks' Herald -- May 6, 2010 Roger Williams University

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Hawk's Herald Student Publications 5-6-2010 Hawks' Herald -- May 6, 2010 Roger Williams University Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.rwu.edu/hawk_herald Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Roger Williams University, "Hawks' Herald -- May 6, 2010" (2010). Hawk's Herald. Paper 125. http://docs.rwu.edu/hawk_herald/125 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hawk's Herald by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Fray and Four Unpaid internships: Year Strong perform Legal or not? See pages 6 and 7 See page4 The student"newspaper of Roger Williams University Bristol, R.I. 02809 Thursday, May 6, 2010 Double and triple majors get single diploma Bayside courtyard Amanda Newman graduate. The simple answer to that Business Manager is "When a student graduates, they receive a diploma with their primary packed with partiers As graduation rapidly ap degree printed on it," said Daniel proaches, there is a lot of anticipa Vilenski, University Registrar. Stu Kelleigh Welch was and how they had tion about jobs, new beginnings, dents also receive a copy of their of Editor-in-Chief the ability to throw it. and life after college. However, ficial transcript. "It was freaking there are also a lot of questions But if a transcript is also re Following the end awesome,'' senior about diplomas. ceived, then what is printed on the to a successful Spring David Pullman said. -

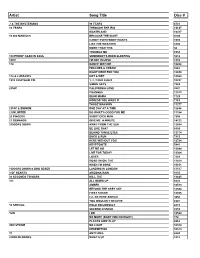

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Good Songs for Sports Slideshow

http://slideshow-studio.com/slideshow/good-songs-sports-slideshow/ Best songs for sports slideshow of all time Upbeat songs could enable athletes to get motivation and to boost their self-confidence. No matter you are an athlete or sports fan, after attending a sports game, there should be many pictures for sharing. If you are planning to work on a sports slideshow with your sports pictures and looking for some upbeat sports theme songs, you could consider the following great sports songs. Slideshow makers you may need to make Sports slideshow with music: 1. DVD Photo Slideshow (for Windows) 2. Photo Slideshow Director HD (for iPad and iPhone) 3. HD Slideshow Maker (for Mac) Best songs for sports slideshow of all time 1. Heart of a Champion – Nelly 2. We are the Champions – Queen 3. Let it Rock – Kevin Rudolph 4. Live to Win – Paul Stanley 5. Simply the Best – Tina Turner 6. The Impossible Dream – Jim Nabors 7. Right Here, Right Now – Fatboy Slim 8. The Second Coming - Juelz Santana 9. We Will Rock You-Queen 10. This Is Why I’m Hot – Mims 11. World In Motion – New Order 12. Rock and Roll Part 2 – Gary Glitter 13. Stand Up – Trapt 14. Inside the Fire – Disturbed 15. Keep Hope Alive – The Crystal Method 16. Get Over It – OK GO 17. Bleed It Out – Linkin Park 18. Crazy Train – Ozzy 19. Kryptonite – 3 Doors Down 20. You’ll Never Walk Alone – Jordin Sparks 21. Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger – Daft Punk 22. Superstar – Lupe Fiasco 23. Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen 24. -

Three Soldiers

THREE SOLDIERS BY A PENN STATE ELECTRONIC CLASSICS SERIES PUBLICATION JOHN DOS PASSOS Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos is a publication of the Pennsylvania State University. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any purpose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State Uni- versity nor Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos, the Pennsylvania State University, Electronic Classics Series, Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA 18202 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing student publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them. Cover Design: Jim Manis Copyright © 2004 The Pennsylvania State University The Pennsylvania State University is an equal opportunity university. John Dos Passos cooking. At the other side of the wide field long lines of men THREE SOLDIERS shuffled slowly into the narrow wooden shanty that was the mess hall. Chins down, chests out, legs twitching and tired BY from the afternoon’s drilling, the company stood at atten- tion. Each man stared straight in front of him, some va- cantly with resignation, some trying to amuse themselves by JOHN DOS PASSOS noting minutely every object in their field of vision,—the cinder piles, the long shadows of the barracks and mess halls 1921 where they could see men standing about, spitting, smok- “Les contemporains qui souffrent de certaines choses ne ing, leaning against clapboard walls. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Music in the Digital Age: Musicians and Fans Around the World “Come Together” on the Net

Music in the Digital Age: Musicians and Fans Around the World “Come Together” on the Net Abhijit Sen Ph.D Associate Professor Department of Mass Communications Winston-Salem State University Winston-Salem, North Carolina U.S.A. Phone: (336) 750-2434 (o) (336) 722-5320 (h) e-mail: [email protected] Address: 3841, Tangle Lane Winston-Salem, NC. 27106 U.S.A. Bio: Currently an Associate Professor in the Department of Mass Communications, Winston-Salem State University. Research on international communications and semiotics have been published in Media Asia, Journal of Development Communication, Parabaas, Proteus and Acta Semiotica Fennica. Teach courses in international communications and media analysis. Keywords: music/ digital technology/ digital music production/music downloading/ musicians on the Internet/ music fans/ music software Abstract The convergence of music production, creation, distribution, exhibition and presentation enabled by the digital communications technology has swept through and shaken the music industry as never before. With a huge push from the digital technology, music is zipping around the world at the speed of light bringing musicians, fans and cultures together. Digital technology has played a major role in making different types of music accessible to fans, listeners, music lovers and downloaders all over the world. The world of music production, consumption and distribution has changed, and the shift is placing the power back into the hands of the artists and fans. There are now solutions available for artists to distribute their music directly to the public while staying in total control of all the ownership, rights, creative process, pricing, release dates and more. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

“Savage Tales”

“SAVAGE TALES” By Damián Szifron Copyright 2012 Big Bang – Buenos Aires, Argentina. Table of Contents Pasternak.........................2 The Rats..........................9 Road to Hell.....................18 ‘Til Death Do Us Part............26 The Deal.........................47 Firecracker......................68 Bonus Track......................83 On a white background, the title of the first story appears in block letters: 1 PASTERNAK INT. AIRPORT CHECK-IN. DAY. ISABEL, an attractive woman of around 30, runs with a small suitcase up to the counter of one of the airlines. ISABEL Will I make it? AIRLINE ATTENDANT ID and e-ticket, please. ISABEL (handing them over) A company paid for the ticket—do you know if I can get the miles on my account? AIRLINE ATTENDANT This fare doesn’t give you any miles. ISABEL Oh, forget it then. The attendant prints out and stamps the boarding pass. AIRLINE ATTENDANT The flight is already boarding—it’s gate three. CUT TO: INT. AIRPLANE. DAY. Isabel reaches up to put her suitcase inside the luggage compartment and notices that SALGADO, the 60-year-old man with a grey beard sitting next to her, is checking out her cleavage. Salgado realizes that Isabel has noticed and he pretends to want to help instead. SALGADO Can you manage? ISABEL Yes, I’ve got it. Thanks. Salgado turns his attention back to the book he is reading. CUT TO: 2 EXT. AIRPORT RUNWAY. DAY. The airplane pauses on the airstrip, taxis down the runway and takes off. INT. AIRPLANE. DAY. Once the plane has reached its flying altitude, Salgado strikes up a conversation with Isabel. -

Praise Songs

When I Consider Your Heavens Songs of Worship & Praise 4 .1 Compiled by Dwayne Kingry Printed 2008 Praise and Worship When I Consider Your Heavens Praise and Worship v4.1 A Quiet Place [001] Above All [002] C E7 (Verse) There is a quiet place G/B C D G Am C7 Fmaj7 Above all powers above all kings Far from the rapid pace where God G/B C D G A7 D7 G9 Above all nature and all created things Can soothe my troubled mind D/F# Em D C G/B Gm9 C9 Above all wisdom and all the ways of man Sheltered by tree and flower C Am7 D G F9 Dm Am You were here before the world began There in my quiet hour with Him G/B C D G B7 E Dm7 G7 Above all kingdoms above all thrones My cares are left behind G/B C D G C E7 Above all wonders the world has ever known Whether a garden small D/F# Em D C G/B Am C7 Above all wealth and treasures of the earth Or on a mountain tall C Am7 B7 F Bm7 E7 Am C7 There's no way to measure what You're worth New strength and courage there I find F Fm6 Em (Chorus) Then from this quiet place I go G C D G Em7 A7 Dm7 Crucified laid behind a stone Prepared to face a new day G C D G G9 Dm7 G7 C You lived to die rejected and alone With love for all mankind D/F# Em D C G/B Like a rose trampled on the ground C G/B C D You took the fall and thought of me G Above all (Verse) (Chorus x2) D/F# Em D C G/B Like a rose trampled on the ground C G/B C D You took the fall and thought of me G Above all Page 1 of 218 When I Consider Your Heavens Praise and Worship v4.1 Adonai [003] Agnus Dei [004] (Capo 1st Fret) G C G Em C Intro: Gsus G G/B C Alleluia, alle---luia -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's