Cult of Masculinity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

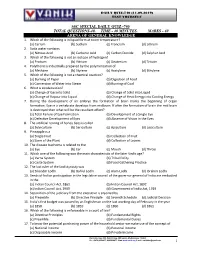

Ssc Special Daily Quiz -740 Total Questions-40, Time - 40 Minutes, Marks - 40 Arena of General Knowledge 1

DAILY QUIZ-740 (11.09.2019) TEST YOURSELF SSC SPECIAL DAILY QUIZ -740 TOTAL QUESTIONS-40, TIME - 40 MINUTES, MARKS - 40 ARENA OF GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. Which of the following is in liquid form at room temperature? (a) Cerium (b) Sodium (c) Francium (d) Lithium 2. Soda water contains (a) Nitrous Acid (b) Carbonic Acid (c) Carbon Dioxide (d) Sulphur Acid 3. Which of the following is not an isotope of hydrogen? (a) Protium (b) Yttrium (c) Deuterium (d) Trituim 4. Polythene is industrially prepared by the polymerization of (a) Methane (b) Styrene (c) Acetylene (d) Ethylene 5. Which of the following is not a chemical reaction? (a) Burning of Paper (b) Digestion of Food (c) Conversion of Water into Steam (d) Burning of Coal 6. What is condensation? (a) Change of Gas into Solid (b) Change of Solid into Liquid (c) Change of Vapour into Liquid (d) Change of Heat Energy into Cooling Energy 7. During the development of an embryo the formation of brain marks the beginning of organ formation. Eye in a vertebrate develops from midbrain. If after the formation of brain the mid brain is destroyed then what will be the resultant effect? (a) Total Failure of Eye Formation (b) Development of a Single Eye (c) Defective Development of Eyes (d) Absence of Vision in the Eyes 8. The artificial rearing of honey bees is called (a) Sylviculture (b) Sericulture (c) Apiculture (d) Lociculture 9. Pineapple is a (a) Single Fruit (b) Collection of Fruit (c) Stem of the Plant (d) Collection of Leaves 10. The disease trachoma is related to the (a) Eye (b) Ear (c) Mouth (d) Throat 11. -

To Download As

Registered with the Reg. No. TN/CH(C)/374/18-20 Registrar of Newspapers Licenced to post without prepayment for India under R.N.I. 53640/91 Licence No. TN/PMG(CCR)/WPP-506/18-20 Publication: 1st & 16th of every month Rs. 5 per copy (Annual Subscription: Rs. 100/-) INSIDE Short ‘N’ Snappy The Music Season The Bharati Debate Cre-A Ramakrishnan Ranji Trophy, 1934 www.madrasmusings.com WE CARE FOR MADRAS THAT IS CHENNAI Vol. XXX No. 12 December 1-15, 2020 A new reservoir OLD AND NEW ¶ after 76 years n November 21, 2020, the Poondi Reservoir scheme was as much and yet it took us 76 OUnion Home Minister, approved in August 1940 and years to build a new facility. Amit Shah, inaugurated the the foundation stone laid on It is not as though nothing fifth reservoir of the city, locat- the 8th of that month. The has been done in the interim. ed at Thervoy Kandigai in Thi- construction was completed We have had the Telugu Ganga ruvallur District. It will have four years later, by when Sa- scheme, we have harnessed a capacity of one thousand tyamurti was dead. The storage the Palar, requisitioned the million cubic feet (1 tmcft) and facility was rather appropriately Veeranam lake and also got is expected to go a long way in named Satyamurti Sagar in his the Chemparampakkam water- solving the water crises that memory. With a capacity of body to cater to our insatiable the city faces in most years. It 2,573 mcft, it is of course small- thirst. -

9789004400139 Webready Con

Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Gonda Indological Studies Published Under the Auspices of the J. Gonda Foundation Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Edited by Peter C. Bisschop (Leiden) Editorial Board Hans T. Bakker (Groningen) Dominic D.S. Goodall (Paris/Pondicherry) Hans Harder (Heidelberg) Stephanie Jamison (Los Angeles) Ellen M. Raven (Leiden) Jonathan A. Silk (Leiden) volume 19 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/gis Vedic Cosmology and Ethics Selected Studies By Henk Bodewitz Edited by Dory Heilijgers Jan Houben Karel van Kooij LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NC 4.0 License, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bodewitz, H. W., author. | Heilijgers-Seelen, Dorothea Maria, 1949- editor. Title: Vedic cosmology and ethics : selected studies / by Henk Bodewitz ; edited by Dory Heilijgers, Jan Houben, Karel van Kooij. Description: Boston : Brill, 2019. | Series: Gonda indological studies, ISSN 1382-3442 ; 19 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019013194 (print) | LCCN 2019021868 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004400139 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004398641 (hardback : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Hindu cosmology. | Hinduism–Doctrines. | Hindu ethics. Classification: LCC B132.C67 (ebook) | LCC B132.C67 B63 2019 (print) | DDC 294.5/2–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019013194 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 1382-3442 ISBN 978-90-04-39864-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-40013-9 (e-book) Copyright 2019 by Henk Bodewitz. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, Vol. 49, No. 2

( 4) Journalof Indian and Buddhist Studies , Vol. 49, No. 2, March2001 King Prthu and His Genealogy Miwako KATO The story of king Prthu is often told to explain the origin of kingship . The following is the outline of the legend. Once there was a king named Vena, who was so impious that the sages slew him. Since he had no son, the sages churned the left hand of the wicked king . Then from the left hand came out a short and black barbarian Nisada. They then churned his right hand and great Prthu was born. Brahma consecrated him as the first king (adiraja), and in the midst of the ritual, two bards, Suta and Magadha were born to praise him. As a result of Vena's evil rule, people had been emaciated for want of food. In order to restore prosperity to them, taking up his bow and arrow, Prthu pursued the Earth who had assumed the form of a cow. Then the Earth begged for mercy and she entreated him to provide her with a calf so that she could give milk out of affection. After adopting Svayambhuva Manu as the calf, Prthu milked plants and vegetables from the Earth-cow on its own surface . Almost all of these elements occur in every version of the Prthu myth . Regarding his ancestor the texts differ from each other. That is, the texts of this story can be classified into three groups according to genealogical accounts of king Prthu. Some of the Puranns (P) such as the Harivamsa (H), Brahma-P. -

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes

Annual Report 2015-2016 Research Themes The research themes of the initiative are explored through public lectures, seminars, conferences, films, research projects, and outreach.� The Initiative currently conducts research on the following themes: 1 Indian Urbanization: Governance, Politics and Political Economy 2 Economic Inequalities and Change 3 Pluralism and Diversities 4 Democracy Above: Engaged audience at Student Fellowship Presentation Front Cover: Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus at Sunset. Mumbai, India. Image: Paul Prescot 1 OP Jindal Distinguished Lecture Series To promote a serious discussion of politics, economics, social and cultural change in modern India, Sajjan and Sangita Jindal have endowed, in perpetuity, the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures by major scholars and public figures.� Fall 2015 MONTEK SINGH AHLUWALIA and also in books. He co-authored Re-distribution In October 2015, Montek Singh Ahluwalia with Growth: An Approach to Policy (1975). He delivered the OP Jindal Distinguished Lectures. also wrote, “Reforming the Global Financial Ahluwalia has served as a high-level government Architecture”, which was published in 2004 as official in India, as well as with the IMF and the Economic paper No.41 by the Commonwealth World Bank. He has been a key figure in India’s Secretariat, London. Ahluwalia is an honorary economic reforms since the mid-1980s. Most fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford and a member recently, Ahluwalia was Deputy Chairman of the of the Governing Council of the Global Green Planning Commission from July 2004 till May Growth Institute, a new international organization 2014. In addition to this Cabinet level position, based in South Korea. He is a member of the Ahluwalia was a Special Invitee to the Cabinet Alpbach-Laxenburg Group established by the and several Cabinet Committees. -

Formative Years

CHAPTER 1 Formative Years Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, a seaside town in western India. At that time, India was under the British raj (rule). The British presence in India dated from the early seventeenth century, when the English East India Company (EIC) first arrived there. India was then ruled by the Mughals, a Muslim dynasty governing India since 1526. By the end of the eighteenth century, the EIC had established itself as the paramount power in India, although the Mughals continued to be the official rulers. However, the EIC’s mismanagement of the Indian affairs and the corruption among its employees prompted the British crown to take over the rule of the Indian subcontinent in 1858. In that year the British also deposed Bahadur Shah, the last of the Mughal emperors, and by the Queen’s proclamation made Indians the subjects of the British monarch. Victoria, who was simply the Queen of England, was designated as the Empress of India at a durbar (royal court) held at Delhi in 1877. Viceroy, the crown’s representative in India, became the chief executive-in-charge, while a secretary of state for India, a member of the British cabinet, exercised control over Indian affairs. A separate office called the India Office, headed by the secretary of state, was created in London to exclusively oversee the Indian affairs, while the Colonial Office managed the rest of the British Empire. The British-Indian army was reorganized and control over India was established through direct or indirect rule. The territories ruled directly by the British came to be known as British India. -

Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Columbia University Academic Commons Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2013 © 2013 Anuj Bhuwania All rights reserved ABSTRACT Competing Populisms: Public Interest Litigation and Political Society in Post-Emergency India Anuj Bhuwania This dissertation studies the politics of ‘Public Interest Litigation’ (PIL) in contemporary India. PIL is a unique jurisdiction initiated by the Indian Supreme Court in the aftermath of the Emergency of 1975-1977. Why did the Court’s response to the crisis of the Emergency period have to take the form of PIL? I locate the history of PIL in India’s postcolonial predicament, arguing that a Constitutional framework that mandated a statist agenda of social transformation provided the conditions of possibility for PIL to emerge. The post-Emergency era was the heyday of a new form of everyday politics that Partha Chatterjee has called ‘political society’. I argue that PIL in its initial phase emerged as its judicial counterpart, and was even characterized as ‘judicial populism’. However, PIL in its 21 st century avatar has emerged as a bulwark against the operations of political society, often used as a powerful weapon against the same subaltern classes whose interests were so loudly championed by the initial cases of PIL. In the last decade, for instance, PIL has enabled the Indian appellate courts to function as a slum demolition machine, and a most effective one at that – even more successful than the Emergency regime. -

Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived

Dr. Sunita B. Nimavat [Subject: English] International Journal of Vol. 2, Issue: 4, April-May 2014 Research in Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Khushwantnama -The Essence of Life Well- Lived DR. SUNITA B. NIMAVAT N.P.C.C.S.M. Kadi Gujarat (India) Abstract: In my research paper, I am going to discuss the great, creative journalist & author Khushwant Singh. I will discuss his views and reflections on retirement. I will also focus on his reflections regarding journalism, writing, politics, poetry, religion, death and longevity. Keywords: Controversial, Hypocrisy, Rejects fundamental concepts-suppression, Snobbish priggishness, Unpalatable views Khushwant Singh, the well known fiction writer, journalist, editor, historian and scholar died at the age of 99 on March 20, 2014. He always liked to remain controversial, outspoken and one who hated hypocrisy and snobbish priggishness in all fields of life. He was born on February 2, 1915 in Hadali now in Pakistan. He studied at St. Stephen's college, Delhi and king's college, London. His father Shobha Singh was a prominent building contractor in Lutyen's Delhi. He studied law and practiced it at Lahore court for eight years. In 1947, he joined Indian Foreign Service and worked under Krishna Menon. It was here that he read a lot and then turned to writing and editing. Khushwant Singh edited ‘ Yojana’ and ‘ The Illustrated Weekly of India, a news weekly. Under his editorship, the weekly circulation rose from 65000 copies to 400000. In 1978, he was asked by the management to leave with immediate effect. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947.