Strategic Egg Destruction by Brood-Parasitic Cowbirds?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

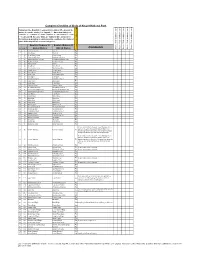

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Leptosomiformes ~ Trogoniformes ~ Bucerotiformes ~ Piciformes

Birds of the World part 6 Afroaves The core landbirds originating in Africa TELLURAVES: AFROAVES – core landbirds originating in Africa (8 orders) • ORDER ACCIPITRIFORMES – hawks and allies (4 families, 265 species) – Family Cathartidae – New World vultures (7 species) – Family Sagittariidae – secretarybird (1 species) – Family Pandionidae – ospreys (2 species) – Family Accipitridae – kites, hawks, and eagles (255 species) • ORDER STRIGIFORMES – owls (2 families, 241 species) – Family Tytonidae – barn owls (19 species) – Family Strigidae – owls (222 species) • ORDER COLIIFORMES (1 family, 6 species) – Family Coliidae – mousebirds (6 species) • ORDER LEPTOSOMIFORMES (1 family, 1 species) – Family Leptosomidae – cuckoo-roller (1 species) • ORDER TROGONIFORMES (1 family, 43 species) – Family Trogonidae – trogons (43 species) • ORDER BUCEROTIFORMES – hornbills and hoopoes (4 families, 74 species) – Family Upupidae – hoopoes (4 species) – Family Phoeniculidae – wood hoopoes (9 species) – Family Bucorvidae – ground hornbills (2 species) – Family Bucerotidae – hornbills (59 species) • ORDER PICIFORMES – woodpeckers and allies (9 families, 443 species) – Family Galbulidae – jacamars (18 species) – Family Bucconidae – puffbirds (37 species) – Family Capitonidae – New World barbets (15 species) – Family Semnornithidae – toucan barbets (2 species) – Family Ramphastidae – toucans (46 species) – Family Megalaimidae – Asian barbets (32 species) – Family Lybiidae – African barbets (42 species) – Family Indicatoridae – honeyguides (17 species) – Family -

The Honeyguide

THE HONEYGUIDE (Children’s Story/Parable) Gary B. Swanson Associate Director General Conference Sabbath School and Personal Ministries “‘I tell you the truth, whoever hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life and will not be condemned; he has crossed over from death to life’” (John 5:24 NIV). In northern Kenya a nomadic tribe of people, the Borans, have learned to communicate in a crude way with a species of birds, known as honeyguides. These birds first draw the attention of humans by swooping close to them, hopping restlessly from branch to branch nearby, and making a persistent call. When the humans approach, the bird disappears over the treetops, but reappears after about 20 minutes to call again and wait for them to proceed further. The Borans follow the birds, all the while whistling, banging sticks together, or talking loudly. This pattern is repeated till the bird and the human reach a beehive in an average of about three hours. Then the Borans enjoy the honey—a staple in their diet—and the honeyguides feast on bee larvae and wax from the honeycombs. Although accounts of this relationship between human and bird have been reported since the 1700s, biologists have only recently documented it. Researchers have found that if they leave the hive to which a bird has led them without breaking into it, the bird will guide them back again and again. This, in a way, is what Bible study does for a Christian. It repeatedly returns the reader to the real source of life, Jesus Christ. -

Notes on Honeyguides in Southeast Cape Province, South Africa

52 SK•AD,Honeyguides ofSoutheast CapeProvince t[AukJan. NOTES ON HONEYGUIDES IN SOUTHEAST CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA BY C. J. SKEAD Now that I am no longer living on a farm it seemsadvisable to collate what little data I have accumulatedon honeyguidesand add it to the scanty knowledgewe have of these birds, in this instance the LesserHoneyguide, Indicator minor minor, the Greater Honeyguide, Indicator indicator, and Wahlberg's Sharp-billed Honeyguide, Pro- dotiscusregulus regulus. The farm "Gameston" where these records were taken lies in the grass-and bush-coveredupper reachesof the Kariega River, 15 miles southwestof Grahamstown, Albany district, Southeast Cape Province, South Africa. This veld-type, known as "bontebosveld," spreads over a large part of the southeastcape. Although I have known the birds for many years the written recordscover a period of about five years. (1) THE LESSERHONEYGUIDE F.colog3.--This speciesprefers the scrub bushyeld and more open acaciaveld, sitting amongthe inner branchesof the trees and bushes but makingconspicuous flights in the openfrom one patch of bushto another. Status.--I have recordedthem in January, February, March, July, August,September, and December. This suggeststhey are resident and not migratory. They are very restlessbirds being seldomseen for more than an hour or so and, in my experience,usually one at a time, even when they parasitized a nest of Black-collared Barbers, Lybius torquatus,in our garden. But from July to September, 1949, two often consortedtogether, attracted, I think, by combs of honey protrudingfrom the gardenbee-hives. There were no barbetsin the garden then. Field Characters.--Thereare no striking features; their dull colora- tion is lightly offset by the golden sheen seen on the back when the light is good. -

Western Birds

WESTERN BIRDS Vol. 49, No. 4, 2018 Western Specialty: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker Second-cycle or third-cycle Herring Gull at Whiting, Indiana, on 25 January 2013. The inner three primaries on each wing of this bird appear fresher than the outer primaries. They may represent the second alternate plumage (see text). Photo by Desmond Sieburth of Los Angeles, California: Golden-cheeked Woodpecker (Melanerpes chrysogenys) San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico, 30 December 2016 Endemic to western mainland Mexico from Sinaloa south to Oaxaca, the Golden-cheeked Woodpecker comprises two well-differentiated subspecies. In the more northern Third-cycle (or possibly second-cycle) Herring Gull at New Buffalo, Michigan, on M. c. chrysogenys the hindcrown of both sexes is largely reddish with only a little 14 September 2014. Unlike the other birds illustrated on this issue’s back cover, in this yellow on the nape, whereas in the more southern M. c. flavinuchus the hindcrown is individual the pattern of the inner five primaries changes gradually from feather to uniformly yellow, contrasting sharply with the forehead (red in the male, grayish white feather, with no abrupt contrast. Otherwise this bird closely resembles the one on the in the female). The subspecies intergrade in Nayarit. Geographic variation in the outside back cover, although the prealternate molt of the other body and wing feathers Golden-cheeked Woodpecker has not been widely appreciated, perhaps because so many has not advanced as far. birders and ornithologists are familiar with the species from San Blas, in the center of Photos by Amar Ayyash the zone of intergradation. Volume 49, Number 4, 2018 The 42nd Annual Report of the California Bird Records Committee: 2016 Records Guy McCaskie, Stephen C. -

The Gambia in Style

The Gambia in Style Naturetrek Tour Report 7 - 14 December 2018 Broad-billed Roller Blue-breasted Kingfisher Western Red Colobus Little Bee-eater Report compiled by Duncan McNiven Images courtesy of Debbie Pain Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report The Gambia in Style Tour participants: Duncan McNiven and Debbie Pain (leaders) plus local guides and 12 Naturetrek clients Day 1 Friday 7th December London Gatwick to Mandina Lodge We all met up at Gatwick Airport for our mid-morning Titan Airways flight to Banjul, the capital of Gambia. Our flight was slightly delayed due to inclement weather but soon enough we were on our way south, leaving behind the mountains and plains of southern Europe and crossing the vast aridness of the Sahara Desert. Eventually, the landscape below us became greener and lusher as we crossed in to Senegal and entered the Guinea Savannah biome. By the time we touched down in Banjul it was already early evening and the light was beginning to wane. Duncan and Debbie were there to meet and greet us and help with acquiring the small amount of local currency we would require for our holiday and in no time at all we were aboard our bus for our short journey to Mandina Lodge. Less than an hour later we were sat under the twinkling fairy lights of the Mandina reception area whilst our gracious host Linda welcomed us and gave us the briefest of briefings before we were all shown to our luxurious lodges nestled amongst the mangroves and forest trees lining the river. -

Adult Brood Parasites Feeding Nestlings and Fledglings of Their Own Species: a Review

J. Field Ornithol., 69(3):364-375 ADULT BROOD PARASITES FEEDING NESTLINGS AND FLEDGLINGS OF THEIR OWN SPECIES: A REVIEW JANICEC. LORENZANAAND SPENCER G. SEALY Departmentof Zoology Universityof Manitoba Winnipeg,Manitoba R3T 2N2 Canada Abstract.--We summarized 40 reports of nine speciesof brood parasitesfeeding young of their own species.These observationssuggest that the propensityto provisionyoung hasnot been lost entirely in brood parasitesdespite the belief that brood parasiticadults abandon their offspringat the time of laying.The hypothesisthat speciesthat participatein courtship feeding are more likely to provisionyoung was not supported:provisioning of young has been observedin two speciesof brood parasitesthat do not courtshipfeed. The function of this provisioningis unknown, but we suggestit may be: (1) a non-adaptivevestigial behavior or (2) an adaptation to ensure adequatecare of parasiticyoung. The former is more likely the case.Further studiesare required to determinewhether parasiticadults commonly feed their genetic offspring. ADULTOS DE AVES PARAS•TICASALIMENTANDO PICHONES Y VOLANTONES DE SU PROPIA ESPECIE: UNA REVISION Sinopsis.--Resumimos40 informes de nueve especiesde avesparasiticas que alimenaron a pichonesde su propia especie.Las observacionessugieren que la propensividadde alimentar a los pichonesno ha sido totalmente perdida en las avesparasiticas, no empecea la creencia de que los parasiticosabandonan su progenie al momento de poner los huevos.La hipttesis de que las especiesque participan en cortejo de alimentacitn, son milspropensas a alimentar los pichonesno tuvo apoyo.Las observacionesde alimentacitn a pichonesse han hecho en dos especiesparasiticas cuyo cortejo no incluye la alimentacitn de la pareja. La funcitn de proveer alimento se desconoce.No obstante,sugerimos que pueda ser: 1) una conducta vestigialno adaptativa,o 2) una adaptacitn parc asegurarel cuidado adecuadode los pi- chonesparasiticos. -

Keeping an Eye on the Sentinel Mutualistic Relationship Between The

Keeping an eye on the sentinel Mutualistic relationship between the honeyguide bird and honey hunters Edmond Dounias IRD, UMR 5175 CEFE, 1919 route de Mende, 34293 Montpellier (France), [email protected] mo è jEE mbÈlÈkÒ y&iè pÒkì kÒ ! If you hear the honeyguide singing, honey is near! Importance of honey hunting among African Pygmies (a Baka pygmy proverb expressing evidence) Honey hunting is a prominent activity among the various groups of African Pygmies. Pygmy hunter-gatherers eagerly look forward to the taste of honey. Honey does not only provide the pleasure of eating, it also functions as a medium by which social relations are regulated. African Pygmies collect honey produced by the honey bee Apis mellifera adansonii and from a dozen different species of stingless bees. Honey harvesting is a seasonal activity that depends on the flowering season of the major nectar sources of the forest. It can be carried out almost continuously from November to June, with picks occurring in February and May. Throughout the Congo Basin, no people other than the Pygmy hunter-gatherers collect honey in such a systematic way. Collecting honey is a characteristic subsistence activity in the tropical forest. There are so many natural hollows suitable for beehive that the successful settlement of bees into artificial hives is highly hazardous. Accordingly, collecting wild honey is much more adaptive to the tropical (© Edmond Dounias) rainforest environment, thus explaining that foragers are much more adapted to other groups to carry out such activity. Birds-Pygmies interactions Whatever the latitude, humans entertain complex relationships with birds, but these interconnections have a particularly high influence on the life of forest foragers. -

Brain Size and Morphology of the Brood-Parasitic and Cerophagous Honeyguides (Aves: Piciformes)

Original Paper Brain Behav Evol Received: August 2, 2012 DOI: 10.1159/000348834 Returned for revision: September 9, 2012 Accepted after second revision: February 10, 2013 Published online: April 24, 2013 Brain Size and Morphology of the Brood-Parasitic and Cerophagous Honeyguides (Aves: Piciformes) e b a, c Jeremy R. Corfield Tim R. Birkhead Claire N. Spottiswoode e d f Andrew N. Iwaniuk Neeltje J. Boogert Cristian Gutiérrez-Ibáñez g f g Sarah E. Overington Douglas R. Wylie Louis Lefebvre a DST/NRF Center of Excellence, Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Cape Town , South Africa; b c Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield , Department of Zoology, d University of Cambridge, Cambridge , and School of Biology, University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews , UK; e f Department of Neuroscience, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alta. , Center for Neuroscience, g University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta. , and Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, Que. , Canada Key Words fers greatly between honeyguides and woodpeckers. The Brain size · Brood parasitism · Hippocampus · Piciformes · relatively smaller brains of the honeyguides may be a conse- Volumetrics quence of brood parasitism and cerophagy (‘wax eating’), both of which place energetic constraints on brain develop- ment and maintenance. The inconclusive results of our anal- Abstract yses of relative HF volume highlight some of the problems Honeyguides (Indicatoridae, Piciformes) are unique among associated with comparative studies of the HF that require birds in several respects. All subsist primarily on wax, are further study. Copyright © 2013 S. Karger AG, Basel obligatory brood parasites and one species engages in ‘guid- ing’ behavior in which it leads human honey hunters to bees’ nests. -

1 Convergent Evolution of Reduced Eggshell Conductance in Avian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Royal Holloway - Pure Convergent evolution of reduced eggshell conductance in avian brood parasites Stephanie C. McClelland1*, Gabriel A. Jamie2,3, Katy S. Waters1, Lara Caldas1, Claire N. Spottiswoode2,3 and Steven J. Portugal1 1School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, Surrey, TW20 0EX, UK. 2Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Downing Street, University of 10 Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK. 3FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, DST-NRF Centre of Excellence, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town, South Africa. Subject Areas: evolution, parasitism, physiology Keywords: Cuculidae, eggs, gas exchange, Indicatoridae, Viduidae Author for Correspondence: Stephanie C. McClelland, email: [email protected] 20 1 Abstract Brood parasitism has evolved independently in several bird lineages, yet these species 30 share many similar physiological traits that optimise this breeding strategy, such as shorter incubation periods and thicker eggshells. Eggshell structure is important for embryonic development as it controls the flux of metabolic gases, such as O2, CO2 and H2O, into and out of the egg; in particular, water vapour conductance (GH2O) is an essential process for optimal development of the embryo. Previous work has shown that common cuckoos (Cuculus canorus) have a lower than expected eggshell GH2O compared to their hosts. Here we sought to test whether this is a trait found in other independently-evolved avian brood parasites, and therefore reflects a general adaptation to a parasitic lifestyle. We analysed GH2O for seven species of brood parasites from four unique lineages as well as for their hosts, and combined this with species 40 from the literature. -

Kruger Comprehensive

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

Southern Tanzania: Endemic Birds & Spectacular Mammals

SOUTHERN TANZANIA: ENDEMIC BIRDS & SPECTACULAR MAMMALS SEPTEMBER 18–OCTOBER 6, 2018 Tanzanian Red-billed Hornbill © Kevin J. Zimmer LEADERS: KEVIN ZIMMER & ANTHONY RAFAEL LIST COMPILED BY: KEVIN ZIMMER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTHERN TANZANIA: ENDEMIC BIRDS & SPECTACULAR MAMMALS September 18–October 6, 2018 By Kevin Zimmer After meeting in Dar es Salaam, we kicked off our inaugural Southern Tanzania tour by taking a small charter flight to Ruaha National Park, at 7,800 square miles, the largest national park in all of east Africa. The scenery from the air was spectacular, particularly on our approach to the park’s airstrip. Our tour was deliberately timed to coincide with the dry season, a time when many of the trees have dropped their leaves, heightening visibility and leaving the landscapes starkly beautiful. This is also a time when the Great Ruaha River and its many smaller tributaries dwindle to shallow, often intermittent “sand rivers,” which, nonetheless, provide natural game corridors and concentration points for birds during a time in which water is at a premium. Bateleur, Ruaha National Park, Sept 2018 (© Kevin J. Zimmer) After touching down at the airstrip, we disembarked to find our trusty drivers, Geitan Ndunguru and Roger Mwengi, each of them longtime friends from our Northern Tanzania tours, waiting for us with their safari vehicles ready for action. The first order of business was to head to the lodge for lunch, but a large, mixed-species coven of Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Southern Tanzania, 2018 vultures could not be ignored, particularly once we discovered the reason for the assemblage—a dead Hippo, no doubt taken down the previous night as it attempted to cross from one river to another, and, the sated Lion that had been gorging itself ever since.