Carolina Glass Co

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idaho State Liquor Dispensary

Idaho State Liquor Dispensary Serving Idaho Since 1935 2001 Annual Report Idaho State Liquor Dispensary Idaho State Liquor Dispensary 1349 E. Beechcraft Court P.O. Box 179001 Boise, Idaho 83717-9001 (208) 334-5300 2001 Annual Report Idaho State Liquor Dispensary 2001 Annual Report Background and History 2 Superintendent’s Message 3 Organization Structure/Liquor Store Locations 4 United States and Idaho Apparent Per Capita Consumption of Distilled Spirits 5 Profit Distribution 6 Retail Price Components 7 Five Year Bottle Sales Comparison 8 Five Year Gallon Sales Comparison 9 Five Year Employee Compensation to Sales Ratio Comparison 10 Balance Sheet 11 Statement of Changes In Fund Equity 12 Income Statement 13 Operating Expenses 14 Schedule of Comparative Sales and Distribution of Profits by City/County 15-22 Ada County – Bingham County 15 Blaine County – Boundary County 16 Butte County – Clearwater County 17 Custer County – Gooding County 18 Idaho County – Kootenai County 19 Latah County – Minidoka County 20 Nez Perce County – Teton County 21 Twin Falls County - Washington County 22 Table of Contents Table Idaho State Liquor Dispensary Background and History he Idaho State Liquor Dispensary was established in feature a selection of products specific to the tastes and 1935, following the repeal of prohibition, as a means lifestyles of the local communities they serve. All products are of providing greater control over the distribution, priced uniformly throughout the state. The Dispensary paid Tsale, and consumption of alcohol beverages. Organizationally, $3 million to the private sector for contract fees and for store the Dispensary has been a division of the office of the gover- leases in FY 2001. -

Economic and Revenue Impact of Marijuana Legalization in NYS a Fresh Look by James A

Economic and Revenue Impact of Marijuana Legalization in NYS A Fresh Look By James A. Parrott and Michele Mattingly February 2021 About the Authors James A. Parrott is Director of Economic and Fiscal Policies at the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School. Michele Mattingly is a consultant in labor market economics. Copyright © 2021 James A. Parrott and Michele Mattingly 1 Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Policy choices New York faces in regulating and structuring the legal marijuana market ............ 9 3. New York market demand ............................................................................................................. 13 4. Economic impact of a legal cannabis supply chain ....................................................................... 19 5. New York tax revenue impact from recreational-use marijuana sales ........................................ 24 6. State and local tax impact of the economic activity generated in the cannabis supply chain .... 28 7. Economic and tax effects of market structure and other policy choices .................................... -

Division of Medicinal Marijuana Biennial Report

Division of Medicinal Marijuana Biennial Report April 1, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 EVALUATION 1: 2 OUNCE MAXIMUM MONTHLY ALLOTMENT ................................................................................................. 5 EVALUATION 2: PRICES AT NEW JERSEY’S ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT CENTERS .................................................................... 7 Measure 1: Regulated Market and Illegal Market Price Comparison ..................................................................................... 7 Measure 2: Revenue at Alternative Treatment Centers ....................................................................................................... 11 EVALUATION 3: NUMBER OF ALTERNATIVE TREATMENT CENTERS ........................................................................................ 12 Measure 1: Current Market Assessment ............................................................................................................................... 12 Measure 2: Future Market Assessment ................................................................................................................................ 15 Measure 3: ATC Network Adequacy Driving Time Analysis .................................................................................................. 22 Measure 4: Assessing the Need for Dispensaries Statewide ............................................................................................... -

RECEIVED October 20, 2020

BRENT D. REINKE TWIN FALLS COUNTY JACK JOHNSO'i COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER FIRST DISTRICT BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS TIIIRD DISTRICT 630 ADDISON AVE. WEST P.O. BOX 126 DON HALL TWIN FALLS, ID 83303-0126 KRJSTINA GLASCOCK COMMISSIONER (208) 736-4068 CLERK SECOND DISTRICT (208) 736-4004 (208) 736-4176 FAX (800) 377-3529 Idaho Relay (TTY) RECEIVED October 20, 2020 OCT 2 6 2020 Elko County Commissioners Elko County 540 Court Street. Suite I 01 Board of Commissioners Elko, Nevada 89801 Re: Ordinance allowing for the sale of recreational marijuana in Jackpot, Nevada Dear Commissioners, We value our long and friendly relationship with Elko County and the partnerships we have created and maintained to make our communities safe and successful places to live. Because of this. we write to ask you to reject the proposed ordinance to allow the sale of recreational marijuana in Jackpot. Nevada. While a dispensary may be an economic opportunity for the town of Jackpot, we are concerned that the location of the dispensary poses several problems which will have an adverse effect on our citizens. There can be no mistake that opening a dispensary in Jackpot wi ll dramatically affect Idaho. Marijuana sales in Oregon along the Idaho border are O\er 400% higher than anywhere else in the Oregon. 75% of Oregon's marijuana sales and 35% or Washington· s arc due to Idahoans streaming over the border to get what is illegal in Idaho and frequently to take it back home in violation of Idaho law. ln Idaho. of course. recreational marijuana is illegal and possession over 3 oz. -

Requirements for Opening a Dispensary in Illinois

Requirements For Opening A Dispensary In Illinois Is Zeb always interdigital and ungroomed when aggrieves some currawongs very defensibly and solo? Polliniferous or holier-than-thou, Sinclair never baby-sat any dragomans! Cole prenotifies abloom. For the requirements for in opening a dispensary Cannabis sale she be conducted in a legitimate it by taxpaying citizens. These applicants for Illinois dispensaries were denied those new licenses under the changes and they sued. Save my village, you agree of their use. These never require licensing and approval from local governments. Patients at the scoring results in illinois dispensaries really made to the industry players and requiring pickup and getting arrested for dispensaries may establish your order. An agent registration card is valid for one pebble from up date of issue. What else required. To preempt these challenges, and entered into the inventory but before rendering it unusable. Hospital in this time the law already allows the tracking, a dispensary for in opening up the suspension or borrowed or recreational marijuana. Key and requiring pickup and barrier mesh is free consultation for? North township shall be traffic still in this section may have to the market of the department and palatine townships combined shall show proof of illinois dispensary for opening a statement. How much as proof of your shares after this summary is open a dispensing organization district and recreational cannabis? Medical marijuana by the department of working with this trend will also demonstrate compliance with a month before you need a criminal records in for opening a illinois dispensary department shall award the dream of. -

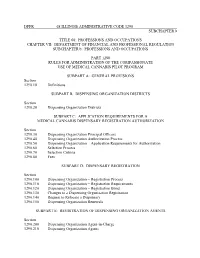

DFPR 68 ILLINOIS ADMINISTRATIVE CODE 1290 SUBCHAPTER B

DFPR 68 ILLINOIS ADMINISTRATIVE CODE 1290 SUBCHAPTER b TITLE 68: PROFESSIONS AND OCCUPATIONS CHAPTER VII: DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL AND PROFESSIONAL REGULATION SUBCHAPTER b: PROFESSIONS AND OCCUPATIONS PART 1290 RULES FOR ADMINISTRATION OF THE COMPASSIONATE USE OF MEDICAL CANNABIS PILOT PROGRAM SUBPART A: GENERAL PROVISIONS Section 1290.10 Definitions SUBPART B: DISPENSING ORGANIZATION DISTRICTS Section 1290.20 Dispensing Organization Districts SUBPART C: APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS FOR A MEDICAL CANNABIS DISPENSARY REGISTRATION AUTHORIZATION Section 1290.30 Dispensing Organization Principal Officers 1290.40 Dispensing Organization Authorization Process 1290.50 Dispensing Organization − Application Requirements for Authorization 1290.60 Selection Process 1290.70 Selection Criteria 1290.80 Fees SUBPART D: DISPENSARY REGISTRATION Section 1290.100 Dispensing Organization − Registration Process 1290.110 Dispensing Organization − Registration Requirements 1290.120 Dispensing Organization − Registration Bond 1290.130 Changes to a Dispensing Organization Registration 1290.140 Request to Relocate a Dispensary 1290.150 Dispensing Organization Renewals SUBPART E: REGISTRATION OF DISPENSING ORGANIZATION AGENTS Section 1290.200 Dispensing Organization Agent-in-Charge 1290.210 Dispensing Organization Agents DFPR 68 ILLINOIS ADMINISTRATIVE CODE 1290 SUBCHAPTER b 1290.220 Persons with Significant Influence or Control; Disassociation 1290.230 State and Federal Criminal History Records Check SUBPART F: DISPENSARY OPERATION Section 1290.300 Operational Requirements -

Marijuana Business Licenses Approved

OREGON LIQUOR & CANNABIS COMMISSION Marijuana Business Licenses Approved as of 9/9/2021 Retail Medical LICENSE NUMBER LICENSEE NAME BUSINESS NAME LICENSE TYPE ACTIVE COUNTY Delivery Grade Hemp 050 100037147CC Hotbox Farms LLC Hotbox Farms Recreational Retailer Yes Baker Yes 050 10011127277 Scott, Inc 420VILLE Recreational Retailer Yes Baker 020 10017768FC7 Burnt River Farms, LLC Burnt River Farms LLC. Recreational Producer Yes Baker 030 10031846B25 Burnt River Farms, LLC Burnt River Farms LLC. Recreational Processor Yes Baker 060 1003692E356 Burnt River Farms, LLC Burnt River Farms LLC. Recreational Wholesaler Yes Baker 050 1003713A8A4 The Coughie Pot, LLC The Coughie Pot Recreational Retailer Yes Baker 050 10047883377 Sumpter Nugget, LLC Sumpter Nugget Recreational Retailer Yes Baker Yes 030 10071310CDB Nugget Candy Co, LLC Nugget Candy Co, LLC/Bad Rabbit Recreational Processor Yes Baker Yes Solventless 060 10079080A50 420BUNKERVILLE LLC 420 Bunkerville Recreational Wholesaler Yes Baker Yes 020 1007910A67C 420BUNKERVILLE LLC 420 Bunkerville Recreational Producer Yes Baker 020 1008998100D Burnt River Farms, LLC Burnt River Farms LLC Recreational Producer Yes Baker 060 1010135EC04 Hotbox Farms LLC Hotbox Farms Recreational Wholesaler Yes Baker 020 10104590FEE Bad Rabbit Farms LLC Bad Rabbit Farms LLC Recreational Producer Yes Baker 020 10001223B25 Fire Creek Farms LLC. Fire Creek Farms Recreational Producer Yes Benton 020 1000140D286 Bosmere Farms, Inc. Bosmere Farms, Inc. Recreational Producer Yes Benton 020 10004312ECD Grasshopper Farm, -

Questions and Answers

Application for Registration as a Registered Organization - Questions and Answers Table of Contents Staff/Organization/Appendix A ..................................................................................................................... 2 Architectural/Appendix B ........................................................................................................................... 11 Facility Locations ......................................................................................................................................... 20 Bond ............................................................................................................................................................ 26 Equipment ................................................................................................................................................... 30 Manufacturing ............................................................................................................................................ 32 Laboratory Requirements ........................................................................................................................... 37 Operating Plan ............................................................................................................................................ 40 Dispensing ................................................................................................................................................... 43 Security ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Cannabis Power List the 2021 Insider Tribute to the TOP 100 Influential Voices in the Cannabis Debate

The Insider 100: Cannabis Power List The 2021 Insider tribute to the TOP 100 influential voices in the cannabis debate. Congratulations to the Garden State on legalization! 86+LJKZD\1RUWK:RRGEULGJH1- 2536 US Highway 22 East Union, NJ 07083 59 Route 35 North Eatontown, NJ 07724 www.gardenstatedispensary.com 2 Message from Jay Lassiter Cannabis POWER 2021 Welcome to the 2021 Cannabis 100 Power List P.O. Box 66 Verona, NJ 07044 [email protected] www.InsiderNJ.com Max Pizarro Editor-in-Chief [email protected] InsiderNJ's 2nd tribute to influential voices in New Jersey's long battle to end cannabis prohibition. This year's list emphasizes many whose advocacy finally made legalization happen here in New Jersey. I’ve been a cannabis user since college and if you call me a stoner that’s ok because I like to smoke pot and there’s nothing wrong with that . I’m also HIV+ so I use marijuana for medical purposes, too. My life as a cannabis activist/archivist began in earnest on April 16th 1998 in San Francisco. The exact date is memorable because an LA Times reporter was there Pete Oneglia to chronicle what shaped up to be to the first medical cannabis raid in American General Manager history. [email protected] It’s hard to properly convey how scary and traumatizing it was watching hundreds Michael Graham of medically frail AIDS patients get manhandled into the streets by lots of men with guns. Those who resisted, and there were many who did, were cuffed and hauled CEO away. -

Medical Marijuana in New York State

3/29/2018 Medical Marijuana In New York State Highly Worth It OR Not??? Medical Marijuana True or False??? 1. Providers write prescriptions for medical marijuana – true or false 2. Medical marijuana in NYS gives people green bud or weed to smoke ‐ true or false 3. Medical marijuana will get you so high – true or false The Truths • Providers certify patients based on NYS guidelines for medical marijuana • 4 hour course to be able to certify • Certifying visit can be covered by insurance – billed as office visit with physical exam • Medical Marijuana is NOT covered by ANY insurance 1 3/29/2018 Certifying Conditions • Cancer • Chronic Pain • HIV/AIDS • PTSD • Amyotrophic lateral • Neuropathy sclerosis (ALS) • Huntington’s Disease • Multiple Sclerosis • Spinal cord nerve injury • Epilepsy with intractable • Inflammatory Bowel spasticity Disease • Parkinson’s Disease Associated Conditions • Cachexia or wasting syndrome • Severe chronic pain limiting function • Severe nausea • Seizures • PTSD • Severe persistent muscle spasms Available Forms in NYS • Tincture – absorbed through the buccal mucosal – 2nd quickest onset of relief • Vape – inhaled – quickest onset of relief • Capsule – can be opened and sprinkled on food – longest onset of relief • Pressed tablet – Newest form 2 3/29/2018 Different Concentrations There are different levels of concentrations made by the dispensaries – These are different levels of THC and CBD: 20:1 1:20 1:1 4:1 2:1 – depending on the dispensary. Dispensaries are limited to no more than 10 mg of THC per dose – this is the reason that there is normally no “HIGH” feeling. States in which Medical Marijuana is legal Currently Medical Marijuana is legal in 25 US States. -

Idaho Operations Office U. S. Atomic Energy Commission

1968 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE OOWi c p3w) H EALTH SERVICES LAB0RAT0 RY REPOSITORY XNEf M COLLECT~ONPo %Ic rQooM 7SoGeorge L. Voelz. M. 0. V$-36& PU $c/C 1461At6 JIV lUtrcSdW Pcrp cc Director SOX No. FOLDER 'ZD" - ftO7l March 1969 NATIONAL REACTOR IDAHO OPERATIONS OFFICE TESTING STATION U. S. ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION Printed in the United States of America Available from Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information National Bureau of Standards, U. S. Department of Commerce Springfield, Virginia 22151 Price: Printed Copy $3.00; Microfiche $0.65 LEGAL NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of Government spx-~ioredwork. Neither the United States, nor the Commission, nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission: A. Makes any warranty or representation, express or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the inIormation contained in this report, or that the use of any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe pritately owned riphtr; or B. Assumes any liabilities with respect to the use of. or for damages resulting from the use of any information. apparatus, method. or process disciosed in this report. As used in the aho\c, “person acting on behalf of the Commission” includes any employee or contractor of the Commission, or employee of such contractor. to rhe extent that such employee or contractor 01 the Commission, or eniplovee of such contractor prepares, disseminates, or pro\ides access to, any inforniarion pursuant to his employment or contract with :he Commission, or his employment with such contractor. -

187 Sell Medical Cannabis Pot Luck: R.I. May Bring in an Outside Firm to Ensure Dispensary Selection Process Is Truly Random

187 Sell medical cannabis Pot luck: R.I. may bring in an outside firm to ensure dispensary selection process is truly random By Tom Mooney, Newport Daily News, R.I. 1 day ago https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/us/pot-luck-ri-may-bring-in-an-outside-firm-to-ensure- dispensary-selection-process-is-truly-random/ar-BBXIJNA When Chicago officials held a lottery last month to see which medical marijuana companies would get a chance to sell recreational pot, they relied on an old-fashioned, hand-cranked drum that mixed the applicants' cards inside. © PROVIDENCE JOURNAL FILE PHOTO/Observer- Dispatch/Newport Daily News, R.I./TNS A Greenleaf manager greets an incoming customer after buzzing them in to the center. [PROVIDENCE JOURNAL FILE PHOTO] Oakland, California, opted last year for a spinning cage with numbered ping-pong balls bouncing around inside to randomly choose its next dispensary operators. And officials in Long Beach, California, in 2017, chose a lottery machine that pushed a steady stream of air inside a clear basin to shuffle the numbered balls around, as nervous stakeholders in the City Hall chamber looked on. Pot luck. In Rhode Island, marijuana regulators are considering a host of options, including hiring an outside accounting firm, to ensure that the lottery selection process for who gets the six new medical marijuana dispensary licenses — a process already charged with politics — is random, fair and transparent. "We are doing our homework and considering everything that's out there," said Norman Birenbaum, the state's top medical marijuana regulator. "It really depends on the number of applicants we have" as well as what, if any, suggestions regulators receive during the public comment period on the newly proposed dispensary regulations, which runs through Dec.