Mao's Last Dancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 1 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X The Boers and the Breaker: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant Re-Viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay is a re-viewing of Breaker Morant in the contexts of New Australian Cinema, the Boer War, Australian Federation, the genre of the military courtroom drama, and the directing career of Bruce Beresford. The author argues that the film is no simple platitudinous melodrama about military injustice—as it is still widely regarded by many—but instead a sterling dramatization of one of the most controversial episodes in Australian colonial history. The author argues, further, that Breaker Morant is also a sterling instance of “telescoping,” in which the film’s action, set in the past, is intended as a comment upon the world of the present—the present in this case being that of a twentieth-century guerrilla war known as the Vietnam “conflict.” Keywords: Breaker Morant; Bruce Beresford; New Australian Cinema; Boer War; Australian Federation; military courtroom drama. Resumen Este ensayo es una revisión del film Consejo de guerra (Breaker Morant, 1980) desde perspectivas como la del Nuevo Cine Australiano, la guerra de los boers, la Federación Australiana, el género del drama en una corte marcial y la trayectoria del realizador Bruce Beresford. El autor argumenta que la película no es un simple melodrama sobre la injusticia militar, como todavía es ampliamente considerado por muchos, sino una dramatización excelente de uno de los episodios más controvertidos en la historia colonial australiana. El director afirma, además, que Breaker Morant es también una excelente instancia de "telescopio", en el que la acción de la película, ambientada en el pasado, pretende ser una referencia al mundo del presente, en este caso es el de una guerra de guerrillas del siglo XX conocida como el "conflicto" de Vietnam. -

Contemporary China: a Book List

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY: Woodrow Wilson School, Politics Department, East Asian Studies Program CONTEMPORARY CHINA: A BOOK LIST by Lubna Malik and Lynn White Winter 2007-2008 Edition This list is available on the web at: http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinabib.pdf which can be viewed and printed with an Adobe Acrobat Reader. Variation of font sizes may cause pagination to differ slightly in the web and paper editions. No list of books can be totally up-to-date. Please surf to find further items. Also consult http://www.princeton.edu/~lynn/chinawebs.doc for clicable URLs. This list of items in English has several purposes: --to help advise students' course essays, junior papers, policy workshops, and senior theses about contemporary China; --to supplement the required reading lists of courses on "Chinese Development" and "Chinese Politics," for which students may find books to review in this list; --to provide graduate students with a list that may suggest books for paper topics and may slightly help their study for exams in Chinese politics; a few of the compiler's favorite books are starred on the list, but not much should be made of this because such books may be old or the subjects may not meet present interests; --to supplement a bibliography of all Asian serials in the Princeton Libraries that was compiled long ago by Frances Chen and Maureen Donovan; many of these are now available on the web,e.g., from “J-Stor”; --to suggest to book selectors in the Princeton libraries items that are suitable for acquisition; to provide a computerized list on which researchers can search for keywords of interests; and to provide a resource that many teachers at various other universities have also used. -

The Getting of Wisdom

The getting film of wisdom Bruce Beresford has learned to accept that lights and camera don’t always mean action, writes Sandra Hall s a Sydney University want to lie and say it’s a masterpiece. student, film director “It might be okay. You just sort of Bruce Beresford (BA’64) hope. You can’t tell, you know.” A had thick, curly dark hair He will allow that it’s a great story. and an intense look that could well What struck him, he says, is the have scored him an audition to play determination shown by Li Cunxin, Byron or Heathcliff. These days, the who realised early on at the Beijing hair has thinned and the intensity Dance Academy that he wasn’t has been moderated by a mingling as naturally gifted as some fellow of self-deprecation, frank practicality students. Yet he worked so hard that and wry amusement at the wonders of he became one of the best. the industry in which he’s worked for A similar tenacity has marked almost 50 years. Beresford’s long career. He’s We meet at a coffee shop in the weathered tough times. Even better, Queen Victoria Building concourse. he’s written about many of them in He hasn’t eaten this morning and one of the frankest and funniest film having already discovered that the memoirs to be published in recent breakfasts here are good value; he years. Josh Hartnett Really Wants To Do orders a hearty bacon and eggs. This recounts his experiences during Newgate Prison on trial for her life. -

Download Press

MAO’S LAST DANCER #28 1-SHEET COMPS_08.27.09 Special Gala Premiere Toronto Film Festival From the Oscar nominated producer and screenwriter of SHINE Directed by Bruce Beresford From the bestselling autobiography by Li Cunxin World Sales Celluloid Dreams Australia - 2009 - 117 min - 1:85 - Dolby SRD - English/Mandarin 2 rue Turgot, 75009 Paris, France T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 [email protected] www.celluloid-dreams.com SYNOPSIS This is the inspirational true story of Li Cunxin, adapted from his best-selling autobiography and telling how, amidst the chaos of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, he was chosen to leave his peasant family and sent on an amazing journey … as it turned out towards freedom and personal triumph. Li’s story unfolds as China was emerging from Mao’s grand vision. It couldn’t have been a better time for Li Cunxin to discover the west and for the west to discover Li Cunxin. This is about how Li overcame adversity, discovering and exploring his natural abilities and talent as a great classical dancer. This meant not only dealing with his own physical limitations but also eventually the punishment meted out by a highly suspicious Chinese government after Li’s defection to the US. In America Li found a completely different and captivating new world – but there were other difficulties he could never have imagined. Even with the support of many friends there was still isolation and despite his growing fame there was still uncertainty for his future. Here is a poignant yet triumphant story, directed by twice Academy nominated director Bruce Beresford (BREAKER MORANT, DRIVING MISS DAISY, TENDER MERCIES, BLACK ROBE etc) from a stunning adaptation by experienced screenwriter, Jan Sardi (SHINE, THE NOTEBOOK, LOVE’S BROTHER etc) that has the ability to touch both worlds. -

2021-QB-Academy-Prospectus.Pdf

Prospectus 2021 CONTENTS Queensland Ballet acknowledges the traditional custodians 02 Academy Director’s welcome of the land on which we train and perform. Long before we 04 About Queensland Ballet Academy arrived on this land, it played host to the dance expression 06 Training and career pathways of our First Nations Peoples. We pay our respects to their Elders, past, present and emerging, and acknowledge 07 Training programs the valuable contribution they have made and continue 08 Kelvin Grove State College to make to the cultural landscape of this country. 10 Career entry programs 11 Workshops and activities 12 Living in Brisbane 14 Academy location and facilities 17 Career development 18 Fostering health and wellbeing 19 Auditions 19 Fees, scholarships and bursaries 21 Our leadership team Photography, unless otherwise labelled — David Kelly 01 ACADEMY DIRECTOR’S WELCOME On behalf of Queensland Ballet, I warmly welcome your consideration of our Academy’s elite training programs. Queensland Ballet Academy takes great pride in nurturing the future custodians of our exquisite artform. Combining world-class ballet training with an emphasis on student wellbeing, our Academy offers a unique educational pathway comparable to the finest international ballet schools. Our current training programs build on the extraordinary expertise of Queensland Ballet’s founder, Charles Lisner OBE. The establishment of the Lisner Ballet Academy in 1953 inspired Queensland Ballet’s commitment to nurturing and developing young dancers. Queensland Ballet Academy honours that legacy. As the official training provider for Queensland Ballet, our graduates have unparalleled access to the Company and its connection to the professional industry and wider dance community. -

3 NOVEMBER | RRP $34.99 | VIKING Also Available As an Ebook and Audiobook Via Audible

3 NOVEMBER | RRP $34.99 | VIKING Also available as an eBook and Audiobook via Audible The highly anticipated memoir of Australian ballerina Mary Li – and the long-awaited sequel to her husband Li Cunxin’s bestselling memoir, Mao’s Last Dancer. Mary McKendry had an idyllic childhood: a rambunctious family full of love and support, in a large Queensland country town, Rockhampton. Here she discovered the joy and beauty of ballet, an art in which she very quickly found herself at home. Mary’s dedication and persistence in excelling shone, opening a world of possibility. At the age of just 16, she flew halfway around the world to start a life in London, studying at the Royal Ballet School. Mary’s talent saw her join the London Festival Ballet, where she danced with the likes of Rudolf Nureyev, and then moved on to Houston Ballet, dancing under acclaimed director Ben Stevenson. Here she met Chinese dancer Li Cunxin: their chemistry ignited the stage, and off stage the two fell in love, becoming darlings of the ballet world. When their first daughter, Sophie, was born, their lives were complete. Mary and Li doted on their precious been.daughter, One doctor and revelled cleared inher their of hearing fortune problems at having - Li’stwice parents - but still,live withthey themnoticed to acare difference for her whenwhile comparedthey were to dancing. On her first birthday they started to notice Sophie wasn’t as responsive to noises as she should have other children. Their fears were confirmed when, at 18 months of age, Sophie was pronounced profoundly deaf. -

Porter Susie.Pdf

sue barnett & associates SUSIE PORTER TRAINING National Institute of Dramatic Art, 1995 FILM Mercy Road Abigail Arclight Films Dir: John Curran Transfusion Magistrate Deeper Water Films Dir: Matt Nable Gold Stranger One/ Rogue Star Productions Stranger Two Dir: Anthony Hayes Beverly (Short) Beverly Curious Films Dir: Roma D’Arrietta Ladies in Black Mrs Miles Samson Productions/The Ruskin Co. Dir: Bruce Beresford The Second Nina Sense and Centsability/STAN Dir: Mairi Cameron Sink (Short) Mother Roger Joyce Dir: Cloudy Rhodes Cargo Kay Causeway Films Dir: Ben Howling/Yolande Remke Don’t Tell Sue Scriven Tojohage Productions/ Scott Corfield Productions Dir: Tori Garrett Hounds of Love Maggie Maloney Factor 30 Films Dir: Ben Young A Priest in the Family (Short) Eileen Dir: Peter Humble/Anni Finsterer Is This the Real World Anna LAD Feature Film Pty Ltd Dir: Martin McKenna The Turning: On Her Knees Carol Arena Media Pty Ltd Dir: Ashlee Page Summer Coda Angela Revival Film Company Dir: Richard Gray Lonely Lonely’s Mum AFTRS The Caterpillar Wish Susan Dir: Sandra Scriberras Little Fish Jenny Porchlight Films Dir: Rowan Woods Teesh and Trude Teesh Dir: Melanie Rodrigues Better Than Sex Cynthia Better Than Sex Productions Dir: Jonathan Teplitsky Mullet Tully Porchlight Films Dir: David Caesar Star Wars: Episode II Hermione Bagwa Dir: George Lucas The Monkey’s Mask Jill Fitzpatrick Arena Film Dir: Samantha Lang Bootmen Sara Hilary Linstead and Associates Dir: Dein Perry Two Hands Deirdre Palm Beach Pictures Dir: Gregor Jordan Feeling Sexy Vicki Binnaburra Film Company Dir: Davida Allen Amy Anny Dir: Nadia Tass Welcome to Woop Woop Angie Dir: Stephen Elliott Paradise Road Oggi Dir: Bruce Beresford Idiot Box Betty Dir: David Caesar Mr. -

Miss Chinatown USA Pays Us a Visit Houston Stars in Mao's Last Dancer

F ASHION LIFESTYLE ART ENTERTAINMENT SEPTEMBER 2010 FREE Miss Chinatown USA Pays Us a Visit Houston Stars in Mao’s Last Dancer Bistro Lancaster Remains a Landmark Old World vs. New World Wine yellowmags.com FROM THE EDITOR IN CHIEF August was a month filled with beauty. I chatted with the reigning Miss Chinatown USA, Miss Crystal Lee, while she was in town to attend the Miss Chinatown Houston pageant. This year marked the 40th anniversary of the pageant and a majority of the past beauty queens appeared on stage to mark the momentous occasion. The newly crowned Houston queen, Miss Joy Le, will represent Houston in the national competition in San Francisco next February. Congratulations! New York City has been getting a lot of press recently in connection with the proposed mosque near Ground Zero. Last year, the city was the center of attention because of the country’s economic woes and the big bonuses that gushed from the big Wall Street firms. We decided to focus on New York, too, but our sights were on the sites to see. There are many that have gone ignored by the mainstream media but which are a lot more interesting and fun (and certainly, much less controversial). It was a big month for the Houston art community, especially for those who love ballet. Li Cunxin was in town to promote the opening of Mao’s Last Dancer, the exquisite new movie based on his best selling autobiography that chronicled his life from provincial China to the stages of Houston’s Wortham Center and Jones Hall. -

Mao's War on Women

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2019 Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 Al D. Roberts Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Al D., "Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976" (2019). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7530. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7530 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAO’S WAR ON WOMEN: THE PERPETUATION OF GENDER HIERARCHIES THROUGH YIN-YANG COSMOLOGY IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PROPAGANDA OF THE MAO ERA, 1949-1976 by Al D. Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Clayton Brown, Ph.D. Julia Gossard, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Li Guo, Ph.D. Dominic Sur, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member _______________________________________ Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 ii Copyright © Al D. Roberts 2019 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Mao’s War on Women: The Perpetuation of Gender Hierarchies Through Yin-Yang Cosmology in the Chinese Communist Propaganda of the Mao Era, 1949-1976 by Al D. -

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People's Republic of China

The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Xin Liu, Chair Professor Vincanne Adams Professor Alexei Yurchak Professor Michael Nylan Professor Shannon Jackson Spring 2011 Abstract The Dialectics of Virtuosity: Dance in the People’s Republic of China, 1949-2009 by Emily Elissa Wilcox Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the University of California, San Francisco in Medical Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Xin Liu, Chair Under state socialism in the People’s Republic of China, dancers’ bodies became important sites for the ongoing negotiation of two paradoxes at the heart of the socialist project, both in China and globally. The first is the valorization of physical labor as a path to positive social reform and personal enlightenment. The second is a dialectical approach to epistemology, in which world-knowing is connected to world-making. In both cases, dancers in China found themselves, their bodies, and their work at the center of conflicting ideals, often in which the state upheld, through its policies and standards, what seemed to be conflicting points of view and directions of action. Since they occupy the unusual position of being cultural workers who labor with their bodies, dancers were successively the heroes and the victims in an ever unresolved national debate over the value of mental versus physical labor. -

A Century of Oz Lit in China: a Critical Overview (1906-2008)

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2011 A century of Oz lit in China: A critical overview (1906-2008) Yu Ouyang University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Ouyang, Yu, A century of Oz lit in China: A critical overview (1906-2008) 2011. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1870 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] A Century of Oz Lit in China: A Critical Overview (1906–2008) OUYANG YU University of Wollongong HIS papER SEEKS TO EXAMINE THE DISSEMINATION, RECEPTION AUSTRALIAN LITERATURE: paRT OF THE LITERATURE FROM “THE and perception of Australian literature in China from WEAK AND SMALL NATIONS” (THE 1920S AND 1930S) T1906 to 2008 by providing a historical background for its first arrival in China as a literature undistinguished Apart from the three Australian poets translated into Chinese from English or American literature, then as part of a ruoxiao in 1921, whom Nicholas Jose mentioned in his paper, another minzu wenxue (weak and small nation literature) in the early poet who found his way to China was Adam Lindsay Gordon, 1930s, its rise as interest grew in Communist and proletarian as Yu Dafu noted in his diary on 18 August 1927.11 So, too, writings in the 1950s and 1960s, and its spread and growth did A. -

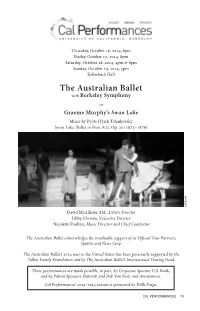

The Australian Ballet with Berkeley Symphony in Graeme Murphy’S Swan Lake Music by Pyotr Il’Yich Tchaikovsky Swan Lake: Ballet in Four Acts , Op

Thursday, October 16, 2014, 8pm Friday, October 17, 2014, 8pm Saturday, October 18, 2014, 2pm & 8pm Sunday, October 19, 2014, 3pm Zellerbach Hall The Australian Ballet with Berkeley Symphony in Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake Music by Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky Swan Lake: Ballet in Four Acts , Op. 20 (1875–1876) y b s u B ff e J David McAllister AM, Artistic Director Libby Christie, Executive Director Nicolette Fraillon, Music Director and Chief Conductor The Australian Ballet acknowledges the invaluable support of its Official Tour Partners, Qantas and News Corp. The Australian Ballet’s 2014 tour to the United States has been generously supported by the Talbot Family Foundation and by The Australian Ballet’s International Touring Fund. These performances are made possible, in part, by Corporate Sponsor U.S. Bank, and by Patron Sponsors Deborah and Bob Van Nest, and Anonymous. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 19 Cal Performances thanks for its support of our presentation of The Australian Ballet in Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake. PLAYBILL PROGRAM Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake Choreography Graeme Murphy Creative Associate Janet Vernon Music Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893): Swan Lake , Op. 20 (1875 –1876) Concept Graeme Murphy, Janet Vernon, and Kristian Fredrikson Set and Costume Design Kristian Fredrikson Original Lighting Design Damien Cooper PROGRAM Act I Scene I Prince Siegfried’s quarters Scene II Wedding festivities INTERMISSION Act II Scene I The sanatorium Scene II The lake INTERMISSION Act III An evening