Responses to the Archaeology for Tbe People Questionnaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Archaeological Evaluation at Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent

Zinch House, Station Road, Stogumber, Somerset Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results OS 1840 Tithe map showing Zinch House Ref: 52568.14 Wessex Archaeology October 2003 ZINCH HOUSE, STATION ROAD, STOGUMBER, TAUNTON, SOMERSET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Document Ref. 52568.14 Prepared for: Wildfire Television Limited 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB October 2003 © Copyright The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003, all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited, Registered Charity No. 287786 ZINCH HOUSE, STATION ROAD, STOGUMBER, TAUNTON, SOMERSET ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Contents Summary .......................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements.......................................................................................5 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................6 1.1 The Site............................................................................................6 1.2 Previous Archaeological Work ........................................................6 2 METHODS .....................................................................................7 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................7 2.2 Aims and Objectives ........................................................................7 -

The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Free Download

THE TIME TEAM GUIDE TO THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN FREE DOWNLOAD Tim Taylor | 320 pages | 05 Jul 2010 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9781905026708 | English | London, United Kingdom The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Goodreads is the world's largest site for readers with over 50 million reviews. I feel really, really angry about it," he told British Archaeology magazine. This book will give you and your family a clear and concise view of what happened when, and why. Available in shop from just two hours, subject to availability. The English and their History. A further hundred activities relating to Roman history were carried out by schools and other institutions around the UK. More Details This item can be requested from the shops shown below. Of course, as a Time Team book, much is made of archaeological evidence and the Team digs feature in each era. Tracy Borman. Not you? BUT on the other side there is the awesome design and presentation of dozens of wide lens photographs of the archeological sites and a similar number of the awesomely detailed pictures Victor Ambrose the programs historical painter contributed to the format which make the book at least visually a proper feast for the eyes and kind of a nice coffee table book to thumb through for the vaguely historically interested person, even when the content of historical information or TV program trivia is a bit underwhelming. Which came first, the Bronze Age or the Stone Age? Alison Weir. Time Team usually does not carry out excavations for these programmes, but may contribute a reconstruction. -

Prehistoric, Environmental and Historical Context

Sutton Hoo 10 Chapter 10 5/12/05 2:12 PM Page 361 Part III Context Sutton Hoo 10 Chapter 10 5/12/05 2:12 PM Page 362 Sutton Hoo 10 Chapter 10 5/12/05 2:12 PM Page 363 Chapter 10 Environment and site formation Martin Carver (with contributions by Charles French and Rob Scaife,and using specialist studies by Steven Rothera) Introduction which can be dug out in lumps (‘crag’). The soil above the The Deben valley runs through a region of sandy flat seaboard subsoil is generally 300–400 mm of well-mixed ploughsoil, territory known as The Sandlings (Figure 13; Plate 1:b). Between either still under the plough, or capped by tough springy turf. them its two rivers, the Deben and the Alde, give access to an Buried soil under the mounds has also been ploughed, and lies archipelago of promontories and islands with woods, pasture, some 250–400 mm thick. arable, meadows, marshland and fishing grounds (Scarfe 1986 The studies described in this chapter concern the and 1987; Warner 1996). The Sutton Hoo cemetery is situated on development of soils and vegetation at the site and its immediate the 33 m (100 ft) contour, on a sand terrace east of the River surroundings. The purpose of these studies was, first, to produce Deben, about 15.5 km (10 miles) upstream from the North Sea – an environmental history for the use of the land before the 10 km (6.25 miles), as the crow flies, from the nearest sea-coast mounds were built and, second, to produce a sequence of the at Hollesley. -

Andrew John Hatton

Stowe Farm, Lincolnshire: A Multi-Period Archaeological Site in its Landscape By: Andrew John Hatton A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Department of Archaeology July 2019 Acknowledgments Firstly, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Doctor Robert Johnston, for his advice and guidance, and for his continued support in the course of this research. Special thanks also go to Professor Mike Parker – Pearson and to Professor Charly French for offering insightful comments. Thanks are due to the staff at Oxford Archaeology East, namely, Gillian Greer, David Brown and Katie Hutton for offering their valuable time during the digitisation of the Stowe Farm site plans. In Addition, I would like to thank Andrew Elliott who volunteered his time to complete the digitisation. Thanks also go to Wayne Granger and Jamie Homewood of University Centre Peterborough for their assistance during the reproduction of the illustrations for this research. Finally, I would like to thank staff at Lincolnshire County Council Historic Environment Record. I would like to dedicate this thesis to my wife, Dr Rebecca Casa. Summary Stowe Farm is located near West Deeping, Lincolnshire, in the Lower Welland Valley, a landscape characterised by the presence of many important archaeological sites discovered during past and more recent gravel extraction. Stowe Farm was one of the many projects instigated by extraction which prompted investigations between 1994 and 2000. However, the analysis of the site was not completed and disseminated. This MPhil project has collated the Stowe Farm archival material and completed the work that was started back in 1994, with the aim to produce a cohesive site narrative and offer further contribution to the characterisation and contextualisation of the rich archaeological landscape of the Lower Welland Valley. -

21 Years of Planning-Led Archaeology in Scotland – and 21 Years More?

21 years of planning-led archaeology in Scotland – and 21 years more? Scottish archaeology has just celebrated a very significant anniversary – not the Battle of Bannockburn or any other historical event – but of 21 years since the introduction of planning guidance (NPPG5) in 1994. This might not sound very impressive at first glance, but it completely revolutionised the way in which the planning process ensures that the historic environment is treated sustainably. Developer-funded archaeological investigations became the norm, in line with the ‘polluter pays’ principle. This single step forward allowed us to gain access to highly significant information about people’s lives in Scotland from the very earliest times, by investigating the traces they have left for future generations to find. These traces are no longer destroyed without due thought or consideration, allowing development to be truly sustainable in terms of the historic environment. Excavation of one of six Roman burials found by CFA Archaeology Ltd, working for Dawn Construction Ltd on the site of the new Musselburgh Primary Health Care Centre. The site was close to the Inveresk Roman fort, and these burials were part of a cemetery associated with the fort in the 2nd century AD. All six of the burials found were men, and four of them had had their heads cut off after death, and placed out of position in the grave. Analysis shows that the men were from Britain and northern Europe, recruited by the Romans from tribes within their Empire and stationed in Inveresk (© CFA Archaeology Ltd) Developer funding Before NPPG5, there was no system in place to check for archaeological remains in advance of building works. -

Alignment and Location of Medieval Rural Churches

ASPECTS OF THE ALIGNMENT AND LOCATION OF MEDIEVAL RURAL CHURCHES by Ian David Hinton being a Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of History, University of East Anglia August 2010 © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on the condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognize that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent St Mary’s and St Lawrence’s, South Walsham, Norfolk - two churches in the same churchyard, but aligned 10° differently ABSTRACT This thesis explores the alignment of medieval rural churches and discusses whether their differing alignments have any specific meaning. It also examines the location of rural church sites and the chronology of church creation in relation to the process of settlement nucleation, the topography of church sites and their possible reuse. A survey of almost 2000 rural medieval churches provides the basis for this study. Part I provides a broad context for the detailed consideration of the results of the survey and their significance. It summarises earlier church alignment studies and the issues that they raise; the practice of alignment more generally; studies of the rural church and its place in the landscape; and earlier studies of medieval rural settlement. Part II describes the survey methodology and its basic results, applies the results to the theories advanced in earlier studies and evaluates them in the light of this new evidence. Part III discusses and analyses two significant variations which have been uncovered: the clear pattern of spatial variation in church alignment between the east and the west of the country, and the fact that between two and three times as many churches were built on east-facing slopes as on west-facing slopes. -

Ta 62 Final Version

Summer 2012 Number 84 The ARCHAEOLOGIST This issue: METAMORPHOSIS: THE CHANGING WORLD OF THE HERITAGE SECTOR Archaeology examined at appeal p29 Jobs in British Archaeology 2011 –2012 p42 HLF Workplace Learning Bursary Scheme Institute for Archaeologists p58 SHEs University of Reading Whiteknights PO Box 227 READING RG6 6AB C ONTENTS 1 Contents 2 Editorial 3 A word from IfA Chief Executive, Peter Hinton page 12 4 Metamorphosis – the changing world of the heritage sector 4 NPPF; the future is in your hands Amanda Forster 6 Aligning strategies; IfA’s strategic plan and the National Heritage Protection Plan Peter Hinton 12 The changing landscape of skills and training Kate Geary 14 Building an archaeologist Andrea Bradley 15 Higher Education in transformation Anthony Sinclair 16 Changing prospects Chris Clarke page 19 17 PPS6: promoting change and adaptation in Northern Ireland Peter Hinton 19 Industrial heritage at risk? Often iconic, extremely tangible and much loved Shane Kelleher 26 Baliscate Chapel: a case study in developing a professionally-led community excavation Andrew Reid, Hylda Marsh, Olive Brown and Jean Whittaker 29 Archaeology examined at appeal Sandy Kidd 32 Opinion: Building Recording: what’s the point? Mike Heaton 35 Response articles 42 Jobs in British archaeology 2011 –2012 Doug Rocks-Macqueen 44 Interview: DigVentures; venturing into the unknown with Brendon Wilkins, Lisa Westcott Wilkins and Raksha Dave page 44 50 Members news 52 New Members page 58 53 Registered Organisations news 53 A SURE Thing? Participative knowledge -

KAFS Newsletter No. 5

KAFS Newsletter: No.5. The Kent Archaeological Field School: Winter-Spring 2008 Heard about the Roman baths at Blacklands? elcome in 2008 to the Anglo-Saxon gilt cruciform brooch. At Blacklands 10th anniversary of the Roman site an earlier geophysical survey by WKent Archaeological English Heritage had identified at least 19 Roman Field School! Yet again an buildings focused around a large depression in amazing year with some important the hillside. It seems the depression was modelled investigations of stunning sites. At in the 4th century with terraces cut into the chalk. Easter we followed up investigations begun in The exotic bath house overlooking this feature 1926 when it was thought that the Roman has the remains of some of the finest full colour cemetery of the Roman town at Syndale was pictorial mosaics found so far in Kent, and a huge located in the Park- it was! The surprise was that timber building had been built on the demolished we found Roman cremation pots scratched with ruins in the 6/7th centuries. Christian symbols and buried with an early Do join us in 2008 for more superb courses. Phil Harding of Time Team and Paul Wilkinson of the Kent Archaeological Field School at Syndale in 2003. Time-Teams investigation led to some wonderful opportunities, of which one was a comprehensive geophysical survey of the Park. Building on this work the Field School has discovered the extent of the Kent Archaeological Field School Roman town, probably called School Farm Oast, Graveney Road, ‘Durolevum’, and this work Faversham, Kent, ME13 8UP continues at Easter 2008. -

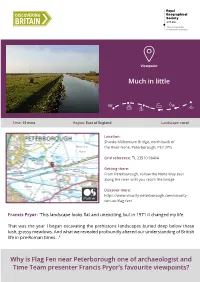

Flag Fen Viewpoint.Pdf

Viewpoint Much in little Time: 15 mins Region: East of England Landscape: rural Location: Shanks Millennium Bridge, north bank of the River Nene, Peterborough, PE7 2PG Grid reference: TL 23510 98404 Getting there: From Peterborough, follow the Nene Way east along the river until you reach the bridge Discover more: https://www.vivacity-peterborough.com/vivacity- venues/flag-fen/ Francis Pryor: “This landscape looks flat and unexciting, but in 1971 it changed my life. That was the year I began excavating the prehistoric landscapes buried deep below these lush, grassy meadows. And what we revealed profoundly altered our understanding of British life in pre-Roman times...” Why is Flag Fen near Peterborough one of archaeologist and Time Team presenter Francis Pryor’s favourite viewpoints? The open landscape south-east of Peterborough conceals the almost perfectly preserved remains of the prehistoric communities who lived here, some two to four thousand years ago. These people settled here because the soil was very fertile and the slow-flowing rivers of the Fens were extraordinarily rich in fish, eels and wildfowl. Huge reed beds provided thatch for roofs and extensive woodlands, timber and firewood. Today these landscapes, together with the men and women who lived in them, lie buried, beneath deep layers of peat and flood-clay. On most ancient sites, only pottery, stone and a few bones survive, but here the wet ground has effectively ‘pickled’ everything. So pots survive, but so does the food cooked inside them. Wooden posts are preserved, along with mats on floors, baskets and fragile fabrics. This landscape has changed enormously over the past few centuries. -

Roughtor, Bodmin Moor, Cornwall

Wessex Archaeology Roughtor, Bodmin Moor, Cornwall Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 62500.01 September 2007 Roughtor, Bodmin Moor, Cornwall Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 62500.01 August 2007 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2007, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Roughtor, Bodmin Moor, Cornwall Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................1 1.1 Project Background ...................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology..................................................1 1.3 Historical and Environmental Background ............................................1 Introduction..................................................................................................1 Mesolithic (8500-4000BC)...........................................................................2 Neolithic (4000-2500 BC)............................................................................2 Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (3000-1500 BC) ......................................2 Middle Bronze Age to Iron Age (1500BC-AD43) ........................................3 1.4 Previous Archaeological -

62505 Stilton Report.Pdf

Wessex Archaeology Stilton, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of the Results Ref: 62505.01 December 2006 Stilton, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON W12 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 62505.01 December 2006 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Stilton, Cambridgeshire Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................1 1.2 Site Location, Topography and Geology..................................................1 1.3 Historical Background...............................................................................1 Roman Arrival..............................................................................................1 Settlement.....................................................................................................2 Pottery Industry............................................................................................2 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work .................................................................3 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES.................................................................................4 -

Britain Ad : a Quest for Arthur, England and the Anglo-Saxons Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BRITAIN AD : A QUEST FOR ARTHUR, ENGLAND AND THE ANGLO-SAXONS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Francis Pryor | 320 pages | 30 Oct 2006 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007181872 | English | London, United Kingdom Britain AD : A Quest for Arthur, England and the Anglo-Saxons PDF Book He also secured final victory in the North, against the Picts and Scots. The legend of King Arthur and Camelot is one of the most enduring in Britain's history, spanning centuries and surviving invasions by Angles, Vikings and Normans. Civilisation declines, cities are deserted, fields overgrown, forests cover the land. A group of Cambridge scientists are working on atomic fission. If you are in it, you might like it. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Download as PDF Printable version. I can just picture him telling his publisher, "But there's no real evidence Over the next thre…. Drawing on a vast range of sources and new translations of early British and Gaelic poetry, Arthur explodes these myths and exposes the shocking truth. Drawing on modern techniques in archaeology and scholarship, they reconstruct the history of the 6th century in Britain, the period when the first unambiguous references to Arthur appear. List of Plates. A fun read, and I think fun for the author to write, but I felt the author was out of his depth, well not out of his depth, because depth is his speciality, perhaps better to say that he was out of his breadth and dealing with specialisms where his knowledge was limited while his enthusiasm was unlimited. Meine Mediathek Hilfe Erweiterte Buchsuche. Merlin warned Vortigern that his end was nigh.