The Acolyte 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of Fc Available for $4.00 From: TRISKELL PRESS P

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of fc Available for $4.00 from: TRISKELL PRESS P. 0. Box 9480 Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1G 3V2 J&u) (B.Mn'^mTuer KOKTAL ADD IHHOHTAl LOVERS TRAPPED Is AS ASCIEST FEUD... 11th ANNUAL FANTASY FAIRS JULY 17, 18, 19, 1981 AMFAC HOTEL MASTERS OF CEREMONIES STEPHEN GOLDIN, KATHLEEN SKY RON WILSON CONTENTS page GUEST OF HONOR ... 4 ■ GUEST LIST . 5 WELCOME TO FANTASY FAIRE by’Keith Williams’ 7 PROGRAM 8 COMMITTEE...................... .. W . ... .10 RULES FOR BEHAVIOR 10 WALKING GUIDE by Bill Conlln 12 MAP OF AREA ........................................................ UPCOMING FPCI CONVENTIONS 14 ADVERTISERS Triskell Press Barry Levin Books Pfeiffer's Books & Tiques Dangerous Visions Cover Design From A Painting By Morris Scott Dollens GUEST OF HONOR FRITZ LEIBER was bom in 1910. Son of a Shakespearean actor, Fritz was at one time an actor himself and a mem ber of his father’s troupe. He made a cameo appearance in the film "Equinox." Fritz has studied many sciences and was once editor of Science Digest. His writing career began prior to World War 11 with some stories in Weird Tales. Soon Unknown published his novel "Conjure Wife, " which was made into a movie under the title (of all things) "Bum, Witch, Bum!" His Gray Mouser stories (which were the inspira tion for the Fantasy Faire "Fritz Leiber Fantasy Award") were started in Unknown and continued in Fantastic, which magazine devoted its entire Nov., 1959 issue to Fritz's stories. In 1959 Fritz was awarded a Hugo, by the World Science Fiction Convention for his novel "The Big Time." His novel "The Wanderer," about an interloper into our solar system, won the Hugo again in 1965.'-His novelettes Gonna Roll the Bones," "Ship of Shadows" and "Ill Met in Lankhmar” won the Hugo in 1968, 1970 and 1971 in that order. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

New Pulp-Related Books and Periodicals Available from Michael Chomko for July 2008

New pulp-related books and periodicals available from Michael Chomko for July 2008 In just two short weeks, the Dayton Convention Center will be hosting Pulpcon 37. It will begin on Thursday, July 31 and run through Sunday, August 3. This year’s convention will focus on Jack Williamson and the 70 th anniversary of John Campbell’s ascension to the editorship of Astounding. There will be two guests-of-honor, science-fiction writers Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. Another highlight will be this year’s auction. It will feature many items from the estate of Ed Kessell, one of the guiding lights of the first Pulpcon. Included will be letters signed by Walter Gibson, E. Hoffmann Price, Walter Baumhofer, and others, as well as a wide variety of pulp magazines. For further information about Pulpcon 37, please visit the convention’s website at http://www.pulpcon.org/ Another highlight of Pulpcon is Tony Davis’ program book and fanzine, The Pulpster . As usual, I’ll be picking up copies of the issue for those of you who are unable to attend the convention. If you’d like me to acquire a copy for you, please drop me an email or letter as soon as possible. My addresses are listed below. Most likely, the issue will cost about seven dollars plus postage. For those who have been concerned, John Gunnison of Adventure House will be attending Pulpcon. If you plan to be at Pulpcon and would like me to bring along any books that I am holding for you, please let me know by Friday, July 25. -

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K

Table of Contents MAIN STORIES American Science Fiction, 1960-1990, Ursula K. ConFrancisco Report........................................... 5 Le Guin & Brian Attebery, eds.; Chimera, Mary 1993 Hugo Awards W inners................................5 Rosenblum; Core, Paul Preuss; A Tupolev Too Nebula Awards Weekend 1994 ............................6 Far, Brian Aldiss; SHORT TAKES: Argyll: A The Preiss/Bester Connection.............................6 Memoir, Theodore Sturgeon; The Rediscovery THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD Delany Back in P rint............................................ 6 of Man: The Complete Short Science Fiction of HWA Changes......................................................6 Cordwainer Smith, Cordwainer Smith. (ISSN-0047-4959) 1992 Chesley Awards W inners............................6 Reviews by Russell Letson:................................21 EDITOR & PUBLISHER Bidding War for Paramount.................................7 The Mind Pool, Charles Sheffield; More Than Charles N. Brown Battle of the Fantasy Encyclopedias................... 7 Fire, Philip Jose Farmer; The Sea’s Furthest ASSOCIATE EDITOR Fantasy Shop Helps AIDS F u n d ......................... 9 End, Damien Broderick. SPECIAL FEATURES Reviews by Faren M iller................................... 23 Faren C. Miller Complete Hugo Voting.......................................36 Green Mars, Kim Stanley Robinson; Brother ASSISTANT EDITORS 1993 Hugo Awards Ceremony........................... 38 Termite, Patricia Anthony; Lasher, Anne Rice; A Marianne -

2256 Inventory 4.Pdf

The Robert Bloch Collection, Acc. ~2256-89-0]-27 Page 11 Box ~ (continueo) Periooicals (continueol: F~ntastic Adyentutes: Vol. 5 (No.8), Allg. 194]: "You Can't Kio Lefty Feep", pp.148-166; "Fairy Tale" under the name Tarleton Fiske, pp.184-202; biographical note on Tarleton Fiske, p.203. Vol. 5 (No.9), Oct. 194]: "A Horse On Lefty Feep", pp. 86-101; "Mystery Of The Creeping Underwear" under the name Tarleton FIske, pp.132-146. Vol. 6 (No.1), Feb. 1944; "Lefty Feep's ~l:abian Nightmare", pp.178-192. Vol. 6 (No. 2), ~pr. 1944: "Lefty Feep Does Time", pp. 156-1'15. Vol. 7 (No.2), Apr. IH5: "Lefty Feep Gets Henpeckeo", 1'1'.116-131. Vol. 6 (No.3), July 1946: "Tree's A Cro"d", pp.74-90. Vol. 9 (No. 51, sept. 1947: "The Mad Scientist", pp. 108-124. Vol. 12 (No.3), Mar. 1950: "Girl From Mars", pp.28-33. Vol. 12 (No.7), July 1950: "End Of YOUl: Rope", 1'p.l10- 124. Vol. 12 (No. S), Aug. 1950: "The Devil With Youl", pp. 8-68. Vol. 13 (No.7), July 1951: "The Dead Don't Die", pp. 8-54; biogl;aphical note, pp.2, 129-130. Fantastic Monsters Of The F11ms, Vol. 1 (No.1), 1962: "Black Lotus", p.10-21, 62. Fantastic Uniyel;se: Vol. 1 (No.6), May 1954: "The Goddess Of Wisdom", pp. 117-128. Vol. 4 (No, 6), Jan. 1956: "You Got To Have Brains", pp .112-120. Vol. 5 (No.6), July 1956: "Founoing Fathel:s", pp.34- Vol. -

INTERVIEW with ROBERT BLOCH - 1 - by Jean-Marc Lofficier

INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT BLOCH - 1 - By Jean-Marc Lofficier INTERVIEW WITH ROBERT BLOCH Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier RL: Who do you consider to be at the root of your inspiration for your writing of terror and horror fiction? RB: Well, I spent eleven years in an advertising agency! Actually, as a child I was interested in reading that sort of thing. But, I was more interested, and I think most imaginative children are, in the mysteries of death, age and cruelty. Why do these things happen? Why do people do these things to one another? An innocent child believes in the protection and security of his daddy and mama, his friends and his safe home environment. Then to read and learn about these things is a great shock. I've done a good deal of talking with many other contemporary writers of this sort of fiction, people like Stephen King, Peter Straub, Richard Matheson and half-a- dozen others. They all had the same experience; they all feel this was their motivation. Some kids don't think about these things particularly, but I did. Particularly when I was hiding under the bed or in the closet after seeing something like Lon Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera for the first time at the age of 8 or 9. I decided, as I guess most of these people did, if you can't lick ‘em, join ‘em. So, I learned the method of what it is that terrifies other people as well. Yet, I tried to do it in a way that is safe. -

Table of Contents STORIES John Bolton; Fear, L

Table of Contents STORIES John Bolton; Fear, L. Ron Hubbard; Midnight Putnam Berkley Group Sold................................... 6 Mass, F. Paul Wilson. The Bantam/Pulphouse Connection...................... 6 Reviews by Carolyn Cushman: ............................ 25 Sci-Fi Channel/Disney Deal ....................................6 The Illusionists, Faren Miller; Druids, Morgan F&SF Seeks Editor...................................................6 Llywelyn; Mythology Abroad, Jody Lynn Nye; THE NEWSPAPER OF THE SCIENCE FICTION FIELD 1991 Nebula Ju ry .....................................................6 Starbridge 3: Shadow World, A.C. Crispin & New HWA Officers .................................................6 Jannean Elliott. SHORT TAKES: Treasure of (ISSN-0047-4959) Science Fiction Book Club Awards........................ 9 Light, Kathleen M. O'Neal; Zone Yellow, Keith EDITOR & PUBLISHER Fantasy Exhibit in New York C ity..........................9 Laumer; Current Confusion, Kitty Grey; By Charles N. Brown THE DATA FILE ron's Child, Carola Dunn. ASSOCIATE EDITOR Soviet Space Sweepstakes........................................7 Short Reviews by Scott Winnett: ....................... 27 Faren C. Miller NEA Compromise Passes....................................... 7 Chillers for Christmas, Richard Dalby, ed.; ASSOCIATE MANAGER Canada Plans Import Restrictions..........................7 The Little Country, Charles de Lint; Rune, Ingram Dumps Small-Press Clients........................ 7 Christopher Fowler; The Illusionists, Faren Shelly -

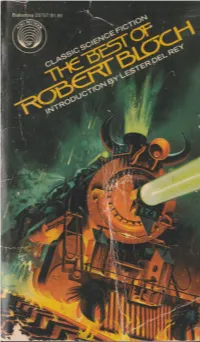

Bloch the Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett the Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L

THE STALKING DEAD The lights went out. Somebody giggled. I heard footsteps in the darkness. Mutter- ings. A hand brushed my face. Absurd, standing here in the dark with a group of tipsy fools, egged on by an obsessed Englishman. And yet there was real terror here . Jack the Ripper had prowled in dark ness like this, with a knife, a madman's brain and a madman's purpose. But Jack the Ripper was dead and dust these many years—by every human law . Hollis shrieked; there was a grisly thud. The lights went on. Everybody screamed. Sir Guy Hollis lay sprawled on the floor in the center of the room—Hollis, who had moments before told of his crack-brained belief that the Ripper still stalked the earth . The Critically Acclaimed Series of Classic Science Fiction NOW AVAILABLE: The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum Introduction by Isaac Asimov The Best of Fritz Leiber Introduction by Poul Anderson The Best of Frederik Pohl Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of Henry Kuttne'r Introduction by Ray Bradbury The Best of Cordwainer Smith Introduction by J. J. Pierce The Best of C. L. Moore Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of John W. Campbell Introduction by Lester del Rey The Best of C. M. Kornbluth Introduction by Frederik Pohl The Best of Philip K. Dick Introduction by John Brunner The Best of Fredric Brown Introduction by Robert Bloch The Best of Edmond Hamilton Introduction by Leigh Brackett The Best of Leigh Brackett Introduction by Edmond Hamilton *The Best of L. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Best of Robert Bloch by Robert Bloch the Best of Robert Bloch by Robert Bloch

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Best of Robert Bloch by Robert Bloch The Best of Robert Bloch by Robert Bloch. The Best Of Fredric Brown by Edited By Robert Bloch. Edited By Robert Bloch. Published by Nelson Doubleday. Used Condition: Very Good. Condition: Very Good. Publisher: Nelson Doubleday, NYC., 1976. Book Club Edition. NEAR FINE hardcover book in VERY GOOD dust- jacket. Spine Tone. Dj has chips at the extremities. NOT remainder marked. NOT price-clipped. NOT faded. NOT ex-library. All of our books with dust-jackets are shipped in fresh, archival-safe mylar protective sleeves. The Best of Robert Bloch. Robert Bloch. Published by Del Rey / Ballantine Books, 1977. Used - Softcover Condition: VERY GOOD. Mass Market Paperback. Condition: VERY GOOD. Light rubbing wear to cover, spine and page edges. Very minimal writing or notations in margins not affecting the text. Possible clean ex-library copy, with their stickers and or stamp(s). More buying choices from other sellers on AbeBooks. GRAVEN IMAGES: The Best of Horror, Fantasy and Science Fiction Film Art from the Collection of Ronald V Borst, Introduction by Stephen King; Reminiscences By Forrest J Ackerman; Clive Barker; Robert Bloch; Ray Bradbury; Harlan Ellison; Peter Straub. Borst, Ronald V with Keith Burns and Leith Adams; Intro by Stephen King; Reminiscences By Forrest J Ackerman; Clive Barker; Robert Bloch; Ray Bradbury; Harlan Ellison; Peter Straub. Published by N.Y. / New York: Grove Press, 1992, 1st Edition, First Printing, New York, NY, 1992. Used - Hardcover Condition: Near Fine (see description) Hard Cover. Condition: Near Fine (see description). Dust Jacket Condition: Near Fine (see description). -

Robert Bloch

ROBERT BLOCH APPRECIATIONS OF THE MASTER EDITED BY RICHARD MATHESON AND RICIA MAINHARDT ® TOR® A TOM DOHERTY ASSOCIATES BOOK / NEW YORK CONTENTS Acknowledgments 11 Introduction by Ricia Mainhardt 15 Douglas E. Winter 17 Frederik Pohl Our Bob 28 Peter Straub 29 Introduces "The Cloak" 32 Gahan Wilson 44 Introduces "Beetles" 48 Andre Norton 57 Christopher Lee 58 William E Nolan 61 Introduces "I Do Not Love Thee, Dr. Fell" 63 Richard Matheson 70 Introduces "Enoch" 74 Hugh B. Cave 85 Introduces "Sweets to the Sweet" 87 Philip Klass (William Tenn) On Robert Bloch 94 Introduces "That Hell-Bound Train" 98 David J. Schow 109 Introduces "The Final Performance" 115 Randall D. Larson Robert Bloch—A Personal Appreciation 125 Introduces "The Pin" 129 Joe R. Lansdale 140 Introduces "The Animal Fair" 143 Jeff Walker Bob, We Bearly Knew Ye ... The Hokas, Hollywood, and Development Hell 154 Introduces Scenes from a Screenplay: Earthman's Burden 157 Introduces "The Plot Is the Thing" 164 Harlan Ellison 170 Introduces "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper" 177 Julius Schwartz The Good Old Days 190 Melissa Ann Singer Lessons 193 Introduces "A Toy for Juliette" 196 Arthur C. Clarke 201 Philip Jose Farmer More Than Most 203 Introduces "All on a Golden Afternoon" 206 Brian Lumley 226 Ramsey Campbell 229 Introduces "Notebook Found in a Deserted House" 231 Bill Warren 246 Introduces "The Clown at Midnight" 250 Mick Garris Four in the Back 258 William Peter Blatty 261 Introduces "A Good Knight's Work" 262 Sheldon Jaffery A Chip Off the Old Bloch 280 Introduces "The Yougoslaves" 283 Stephen King Robert Bloch: An Appreciation 299 Stephen Jones 301 Introduces "The Dead Don't Die!" 304 Neil Gaiman 355 Neil Gaiman and Stephen Jones 358 Introduce "Warning: Death May Be Injurious to Your Health" 359 Ray Bradbury Remembering Bob Bloch 360 Richard Matheson and Ricia Mainhardt 362 Introduce "The Pied Piper Fights the Gestapo" 363 Contributors' Biographies 377 10. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 10-1-1994 SFRA ewN sletter 213 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 213 " (1994). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 153. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SFRA Review Issue #213, September/October 1994 IN THIS ISSUE: SFRA INTERNAL AFFAIRS: President's Message (Mead) 5 Treastrrer's Report (Ewald) 6 SFRA Executive Committee Meeting Minutes (Gordon) 7 SFRA Business Meeting Minutes (Gordon) 10 Campaign Statements and Voting Instructions 12 New Members/Renewals (Evvald) 15 Letters 16 Corrections 18 Editorial (Sisson) 18 NEWS AND INFORMATION 21 SELECfED CURRENT & FORTHCOMING BOOKS 25 FEATURES Special Feattrre: The Pilgrim Award Banquet Pioneer Award Presentation Speech (Gordon) 27 Pioneer Award Acceptance Speech (Tatsumi & McCaffery) 29 Pilgrim Award Presentation Speech (Wendell) 32 Pilgrim Award Acceptance Speech (Clute) 35 REVIEWS: Nonfiction: Asimov, Isaac. 1. Asimov: A Memoir. (Gunn) 41 Cave, Hugh B. Magazines I Remember: Some Pulps, Their Editors, and What It Was Like to Write for Them. (Hall) 43 Fausett, David. Writing the New World: Irnaginary Voyages and Utopias of the Great Southern Land. -

George Pal Papers, 1937-1986

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf2s2004v6 No online items Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Processed by Arts Library-Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by D.MacGill; Arts Library-Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the George Pal 102 1 Papers, 1937-1986 Finding Aid for the George Pal Papers, 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 UCLA Arts Library-Special Collections Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: Art Library-Special Collections staff Date Completed: Unknown Encoded by: D.MacGill © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: George Pal Papers, Date (inclusive): 1937-1986 Collection number: 102 Origination: Pal, George Extent: 36 boxes (16.0 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Shelf location: Held at SRLF. Please contact the Performing Arts Special Collections for paging information. Language: English. Restrictions on Access Advance notice required for access.