Carolee Schneemann: Within and Beyond the Premises Carolee Schneemann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allan Kaprow: the Happenings Are Dead, Long Live the Happenings

1 ALLAN KAPROW: THE HAPPENINGS ARE DEAD, LONG LIVE THE HAPPENINGS Happenings are today's only underground avant-garde. Regularly, since 1958, the end of the Happenings has been announced--always by those who have never come near one--and just as regularly since then, Happenings have been spreading around the globe like some chronic virus, cunningly avoiding the familiar places and occurring where they are least expected. "Where Not To Be Seen: At a Happening," advised Esquire Magazine a year ago, in its annual two-page scoreboard on what's in and out of Culture. Exactly! One goes to the Museum of Modern Art to be seen. The Happenings are the one art activity that can escape the inevitable death-by-publicity to which all other art is condemned, because, designed for a brief life, they can never be over-exposed; they are dead, quite literally, every time they happen. At first unconsciously, then deliberately, they played the game of planned obsolescence, just before the mass media began to force the condition down the throats of the standard arts (which can little afford the challenge). For the latter, the great question has become "How long can it last?"; for the Happenings it always was "How to keep on going?". Thus, "underground" took on a different meaning. Where once the artist's enemy was the smug bourgeois, now he was the hippie journalist. In 1961 I wrote in an article, "To the extent that a Happening is not a commodity but a brief event, from the standpoint of any publicity it may receive, it may become a state of mind. -

Gender Roles in Society Through Judy Chicago's Womanhouse Meagan

Gender Roles in Society through Judy Chicago’s Womanhouse Meagan Howard, Department of Art & Design BFA in Interior Design Womanhouse was an exhibit that was a collaboration of many prominent woman artists’ Abstract: in the 1970s in the California area. This was the Womanhouse was created as an exhibition first female-centered art installation to appear in artwork by Judy Chicago, Miriam Schapiro, and the Western world and it shocked many of the the students of the feminist art program at UCLA people that saw it. Womanhouse raised a series of during the second wave feminist art movement. vitally important questions about how women are Created in an abandoned mansion, the treated in society daily and the gender roles that installations were designed to represent how a have been placed on women since the day they are woman’s life changes once she is married. To born. What made Womanhouse so important was create the concept for each installation, the artists that it was made by women and for women. participated in consciousness-raising sessions Chicago was only keeping women in mind when that allowed them to voice their thoughts and making this piece, because this was meant to feelings on a topic. The kitchen represented the celebrate the essence of being a woman. Men were nurturing side of women that were always only allowed to see Womanhouse so they might caretakers and became mothers to their children. understand the misogyny and gender roles that This work focused on essentialism, the celebration women are required to go through every day. -

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

August 19, 2022 John Dewey and the New Presentation of the Collection

Press contact: Anne Niermann Tel. +49 221 221 22428 [email protected] PRESS RELEASE August 20, 2020 – August 19, 2022 John Dewey and the New Presentation of the Collection of Contemporary Art at the Museum Ludwig Press conference: Wednesday, August 19, 2020, 11 a.m., press preview starting at 10 a.m. For the third time, the Museum Ludwig is showing a new presentation of its collection of contemporary art on the basement level, featuring fifty-one works by thirty-four artists. The works on display span all media—painting, installations, sculpture, photography, video, and works on paper. Artists: Kai Althoff, Ei Arakawa, Edgar Arceneaux, Trisha Baga, John Baldessari, Andrea Büttner, Erik Bulatov, Tom Burr, Michael Buthe, John Cage, Miriam Cahn, Fang Lijun, Terry Fox, Andrea Fraser, Dan Graham, Lubaina Himid, Huang Yong Ping, Allan Kaprow, Gülsün Karamustafa, Martin Kippenberger, Maria Lassnig, Jochen Lempert, Oscar Murillo, Kerry James Marshall, Park McArthur, Marcel Odenbach, Roman Ondak, Julia Scher, Avery Singer, Diamond Stingily, Rosemarie Trockel, Carrie Mae Weems, Josef Zehrer In previous presentations of contemporary art, individual artworks such as A Book from the Sky (1987–91) by Xu Bing and Building a Nation (2006) by Jimmie Durham formed the starting point for issues that determined the selection of the works. This time the work of the American philosopher John Dewey (1859–1952) and his international, still palpable influence in art education serve as a background for viewing the collection. The exhibition addresses the fundamental topics of the relationship between art and society as well as the production and reception of art. -

Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive

Article Dear Sister Artist: Activating Feminist Art Letters and Ephemera in the Archive Kathy Carbone ABSTRACT The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The CalArts Feminist Art Program (1971–1975) played an influential role in this movement and today, traces of the Feminist Art Program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection. Through a series of short interrelated archives stories, this paper explores some of the ways in which women responded to and engaged the Collection, especially a series of letters, for feminist projects at CalArts and the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, University of London over the period of one year (2017–2018). The paper contemplates the archive as a conduit and locus for current day feminist identifications, meaning- making, exchange, and resistance and argues that activating and sharing—caring for—the archive’s feminist art histories is a crucial thing to be done: it is feminism-in-action that not only keeps this work on the table but it can also give strength and definition to being a feminist and an artist. Carbone, Kathy. “Dear Sister Artist,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” eds. Elvia Arroyo- Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies 3. ISSN: 2572-1364 INTRODUCTION The 1970s Feminist Art movement continues to serve as fertile ground for contemporary feminist inquiry, knowledge sharing, and art practice. The California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) Feminist Art Program, which ran from 1971 through 1975, played an influential role in this movement and today, traces and remains of this pioneering program reside in the CalArts Institute Archives’ Feminist Art Materials Collection (henceforth the “Collection”). -

TITLE: Birth Project: the Crowning Q 5 ARTIST: Judy Chicago DATE

TITLE: Birth Project: The Crowning Q 5 ARTIST: Judy Chicago DATE: 1982 SIZE: 56 1/2” x 89” MEDIUM: reverse appliqué and quilting over drawing on fabric ACCESSION #: 97.4 Additional works in the collection by the artist? Yes X No ___ ARTIST’S STATEMENT “Women’s deeds and work need to be a part of permanent history.” Judy Chicago ARTIST’S BIOGRAPHY Judy Chicago is well known for the convention-shattering nature of her work in such monumental, collaborative pro- jects as The Dinner Party, Birth Project, Holocaust Project and Resolutions: A Stitch in Time. As an artist, author, feminist, educator and intellectual whose career now spans more than four decades, she has been a leader and model for an artist’s right to express freely his or her core identity, for a definition of fine art that encompasses craft tech- niques, and for the necessity of an art that seeks to effect social change. Chicago has explored an unusually wide range of media over the course of her career: painting, drawing, printmaking, china-painting, ceramics, tapestry, needlework, and most recently glass. Her fluency with diverse media, her commitment to creating content-based art in the service of social change and her interest in collaboration have led to her being included in the art historical canon—most re- cently in Janson’s Basic History of Western Art. CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION For Chicago, The Birth Project reveals “a primordial female self hidden among the recesses of my soul…. The birth- ing woman, as in The Crowning, is a part of the dawn of creation.” Chicago states, “Traditionally, men make art and women have babies,” so “the Birth Project is an act of solidarity, both with those women who had to choose, and with those who refused to choose.” MEDIA DESCRIPTION The media used in the Birth Project as a whole include fabrics of cotton and silk, needlepoint yarns, threads, and the associated mesh canvases, paint, quilted panels, appliqué, and various other materials usually thought of as women's craft materials, not the materials of “high” art. -

Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann Selected Works 1966 – 1983

Irrigation Veins: Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann Selected Works 1966 – 1983 On view April 30 – May 30, 2020 Ana Mendieta. Volcán, 1979, color photograph Carolee Schneemann, Study for Up to and Including Her Limits, 1973, color © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC photograph, photo credit: Antony McCall Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York Courtesy of the Estate of Carolee Schneemann, Galerie Lelong & Co., and Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York P·P·O·W, New York “These obsessive acts of re-asserting my ties with the earth are really a manifestation of my thirst for being.” Ana Mendieta Galerie Lelong & Co. and P·P·O·W present Irrigation Veins: Ana Mendieta and Carolee Schneemann, Selected Works 1966 – 1983, an online exhibition exploring the artists’ parallel histories, iconographies, and shared affinities for ancient forms and the natural world. Galerie Lelong and P·P·O·W have a history of collaboration and have co-represented Carolee Schneemann since 2017. This will be the first time the two artists are shown together in direct dialogue, an exhibition Schneemann proposed during the last year of her life. In works such as Mendieta’s Volcán (1979) and Schneemann’s Study for Up To and Including Her Limits (1973), both artists harnessed physical action to root themselves into the earth, establishing their ties to the earth and asserting bodily agency in the face of societal restraints and repression. Both artists identified as painters prior to activating their bodies as material; Mendieta received a MA in painting from the University of Iowa in 1972, and Schneemann received an MFA from the University of Illinois in 1961. -

Fresh Meat Rituals: Confronting the Flesh in Performance Art

FRESH MEAT RITUALS: CONFRONTING THE FLESH IN PERFORMANCE ART A THESIS IN Art History Presented to the Faculty of the University of Missouri-Kansas City in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS By MILICA ACAMOVIC B.A., Saint Louis University, 2012 Kansas City, Missouri 2016 © 2016 MILICA ACAMOVIC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FRESH MEAT RITUALS: CONFRONTING THE FLESH IN PERFORMANCE ART Milica Acamovic, Candidate for the Master of Arts Degree University of Missouri-Kansas City, 2003 ABSTRACT Meat entails a contradictory bundle of associations. In its cooked form, it is inoffensive, a normal everyday staple for most of the population. Yet in its raw, freshly butchered state, meat and its handling provoke feelings of disgust for even the most avid of meat-eaters. Its status as a once-living, now dismembered body is a viscerally disturbing reminder of our own vulnerable bodies. Since Carolee Schneeman's performance Meat Joy (1964), which explored the taboo nature of enjoying flesh as Schneeman and her co- performers enthusiastically danced and wriggled in meat, many other performance artists have followed suit and used raw meat in abject performances that focus on bodily tensions, especially the state of the body in contemporary society. I will examine two contemporary performances in which a ritual involving the use of raw meat, an abject and disgusting material, is undertaken in order to address the violence, dismemberment and guilt that the body undergoes from political and societal forces. In Balkan Baroque (1997), Marina Abramović spent three days cleansing 1,500 beef bones of their blood and gristle amidst an installation that addressed both the Serbo-Croatian civil war and her personal life. -

The Unpublished Works of Ana Mendieta Olga Viso

rl-001-076_Mendieta_Lay.qxd:Layout 1 15.07.2008 16:08 Uhr Seite 1 rl-001-076_Mendieta_Lay.qxd:Layout 1 15.07.2008 16:08 Uhr Seite 2 2 rl-001-076_Mendieta_Lay.qxd:Layout 1 15.07.2008 16:09 Uhr Seite 3 UNSEEN MENDIETA THE UNPUBLISHED WORKS OF ANA MENDIETA OLGA VISO PRESTEL MUNICH BERLIN LONDON NEW YORK rl-001-076_Mendieta_Lay.qxd:Layout 1 15.07.2008 16:09 Uhr Seite 4 Cover: Documentation of Feathers on Woman, 1972 (Iowa). Detail of 35 mm color slide Back cover: Documentation of an untitled performance with flowers, ca. 1973 (Intermedia studio, University of Iowa). Detail of 35 mm black-and-white photo negatives Page 1: Untitled (detail), c. 1978. Blank book burnt with branding iron, 13 3⁄16 x111⁄4 in. overall. Collection Des Moines Art Center Permanent Collections, purchased with funds from Rose F. Rosenfield and the Edmundson Art Foundation, Inc. Frontispiece: Ana Mendieta (foreground) and Hans Breder in a field of flowers, Old Man’s Creek, Sharon Center, Iowa, 1977. Detail of 35 mm color slide © Prestel Verlag, Munich · Berlin · London · New York, 2008 © for the text, © Olga M. Viso, 2008 © for the illustrations, © Estate of Ana Mendieta, 2008 All photographs of works by Ana Mendieta are courtesy of Galerie Lelong, New York, unless otherwise indicated. Prestel Verlag, Königinstrasse 9, D-80539 Munich Tel. +49 (89) 242908-300, Fax +49 (89) 242908-335 Prestel Publishing Ltd. 4, Bloomsbury Place, London WC1A 2QA Tel. +44 (020) 7323-5004, Fax +44 (020) 7636-8004 Prestel Publishing, 900 Broadway, Suite 603, New York, N.Y. -

The Performativity of Performance Documentation

THE PERFORMATIVITY OF PERFORMANCE DOCUMENTATION Philip Auslander onsider two familiar images from the history of performance and body art: one from the documentation of Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971), the notori- ous piece for which the artist had a friend shoot him in a gallery, and Yves CKlein’s famous Leap into the Void (1960), which shows the artist jumping out of a second-story window into the street below. It is generally accepted that the first image is a piece of performance documentation, but what is the second? Burden really was shot in the arm during Shoot, but Klein did not really jump unprotected out the window, the ostensible performance documented in his equally iconic image. What difference does it make to our understanding of these images in relation to the concept of performance documentation that one documents a performance that “really” happened while the other does not? I shall return to this question below. As a point of departure for my analysis here, I propose that performance docu- mentation has been understood to encompass two categories, which I shall call the documentary and the theatrical. The documentary category represents the traditional way in which the relationship between performance art and its documentation is conceived. It is assumed that the documentation of the performance event provides both a record of it through which it can be reconstructed (though, as Kathy O’Dell points out, the reconstruction is bound to be fragmentary and incomplete1) and evidence that it actually occurred. The connection between performance and docu- ment is thus thought to be ontological, with the event preceding and authorizing its documentation. -

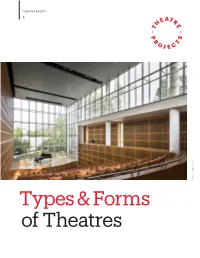

Types & Forms of Theatres

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

Online, Issue 15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002

n.paradoxa online, issue 15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 Editor: Katy Deepwell n.paradoxa online issue no.15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 ISSN: 1462-0426 1 Published in English as an online edition by KT press, www.ktpress.co.uk, as issues 15 and 16, n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal http://www.ktpress.co.uk/pdf/nparadoxaissue15and16.pdf July 2001 and July/Sept 2002, republished in this form: January 2010 ISSN: 1462-0426 All articles are copyright to the author All reproduction & distribution rights reserved to n.paradoxa and KT press. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, including photocopying and recording, information storage or retrieval, without permission in writing from the editor of n.paradoxa. Views expressed in the online journal are those of the contributors and not necessarily those of the editor or publishers. Editor: [email protected] International Editorial Board: Hilary Robinson, Renee Baert, Janis Jefferies, Joanna Frueh, Hagiwara Hiroko, Olabisi Silva. www.ktpress.co.uk n.paradoxa online issue no.15 and 16 July/Sept 2001 and July 2002 ISSN: 1462-0426 2 List of Contents Issue 15, July 2001 Katy Deepwell Interview with Lyndal Jones about Deep Water / Aqua Profunda exhibited in the Australian Pavilion in Venice 4 Two senses of representation: Analysing the Venice Biennale in 2001 10 Anette Kubitza Fluxus, Flirt, Feminist? Carolee 15 Schneemann, Sexual liberation and the Avant-garde of the 1960s Diary