Another Look at the Queen Street Riot Tony Mitchell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nudge, Ahoribuzz and @Peace

GROOVe gUiDe . FamilY owneD and operateD since jUlY 2011 SHIT WORTH DOING tthhee nnuuddggee pie-eyed anika moa cut off your hands adds to our swear jar no longer on shaky ground 7 - 13 sept 2011 . NZ’s origiNal FREE WEEKlY STREET PRESS . ISSUe 380 . GROOVEGUiDe.Co.NZ Untitled-1 1 26/08/11 8:35 AM Going Global GG Full Page_Layout 1 23/08/11 4:00 PM Page 1 INDEPENDENT MUSIC NEW ZEALAND, THE NEW ZEALAND MUSIC COMMISSION AND MUSIC MANAGERS FORUM NZ PRESENT GOING MUSIC GLOBAL SUMMIT WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW BEFORE YOU GO If you are looking to take your music overseas, come and hear from people who are working with both new and established artists on the global stage. DELEGATES APPEARING: Natalie Judge (UK) - Matador Records UK Adam Lewis (USA) - The Planetary Group, Boston Jen Long (UK) - BBC6 New Music DJ/Programmer Graham Ashton (AUS) - Footstomp /BigSound Paul Hanly (USA) - Frenchkiss Records USA Will Larnach-Jones (AUS) - Parallel Management Dick Huey (USA) - Toolshed AUCKLAND: MONDAY 12th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-4PM: BUSINESS LOUNGE, THE CLOUD, QUEENS WHARF RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SHED10, QUEENS WHARF FEATURING: COLLAPSING CITIES / THE SAMI SISTERS / ZOWIE / THE VIETNAM WAR / GHOST WAVE / BANG BANG ECHE! / THE STEREO BUS / SETH HAAPU / THE TRANSISTORS / COMPUTERS WANT ME DEAD WELLINGTON: WEDNESDAY 14th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-5PM: WHAREWAKA, WELLINGTON WATERFRONT RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SAN FRANCISCO BATH HOUSE FEATURING: BEASTWARS / CAIRO KNIFE FIGHT / GLASS VAULTS / IVA LAMKUM / THE EVERSONS / FAMILY CACTUS PART OF THE REAL NEW ZEALAND FESTIVAL www.realnzfestival.com shit Worth announciNg Breaking news Announcements Hello Sailor will be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the APRA Silver Scroll golDie locks iN NZ Awards, which are taking place at the Auckland Town Hall on the 13th Dates September 2011. -

Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020

ORGANIZATION OF ISLAMIC COOPERATION Political Affairs Department Islamophobia Observatory Islamophobia Monitoring Month: December 2020 OIC Islamophobia Observatory Issue: December 2020 Islamophobia Status (DEC 20) Manifestation Positive Developments 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Asia Australia Europe International North America Organizations Manifestations Per Type/Continent (DEC 20) 9 8 7 Count of Discrimination 6 Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 5 Count of Hate Speech Count of Online Hate 4 Count of Hijab Incidents 3 Count of Mosque Incidents 2 Count of Policy Related 1 0 Asia Australia Europe North America 1 MANIFESTATION (DEC 20) Count of Discrimination 20% Count of Policy Related 44% Count of Verbal & Physical Assault 10% Count of Hate Speech 3% Count of Online Hate Count of Mosque Count of Hijab 7% Incidents Incidents 13% 3% Count of Positive Development on Count of Positive POSITIVE DEVELOPMENT Inter-Faiths Development on (DEC 20) 6% Hijab 3% Count of Public Policy 27% Count of Counter- balances on Far- Rights 27% Count of Police Arrests 10% Count of Positive Count of Court Views on Islam Decisions and Trials 10% 17% 2 MANIFESTATIONS OF ISLAMOPHOBIA NORTH AMERICA IsP140001-USA: New FBI Hate Crimes Report Spurs U.S. Muslims, Jews to Press for NO HATE Act Passage — On November 16, the USA’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), released its annual report on hate crime statistics for 2019. According to the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council (MJAC), the report grossly underestimated the number of hate crimes, as participation by local law enforcement agencies in the FBI's hate crime data collection system was not mandatory. -

Let's Face It, the 1980'S Were Responsible for Some Truly Horrific

80sX Let’s face it, the 1980’s were responsible for some truly horrific crimes against fashion: shoulder-pads, leg-warmers, the unforgivable mullet ! What’s evident though, now more than ever, is that the 80’s provided us with some of the best music ever made. It doesn’t seem to matter if you were alive in the 80’s or not, those songs still resonate with people and trigger a joyous reaction for anyone that hears them. Auckland band 80sX take the greatest new wave, new romantic and synth pop hits and recreate the magic and sounds of the 80’s with brilliant musicianship and high energy vocals. Drummer and programmer Andrew Maclaren is the founding member of multi platinum selling band stellar* co-writing mega hits 'Violent', 'All It Takes' and 'Taken' amongst others. During those years he teamed up with Tom Bailey from iconic 80’s band The Thompson Twins to produce three albums, winning 11 x NZ music awards, selling over 100,000 albums and touring the world. Andrew Thorne plays lead guitar and brings a wealth of experience to 80’sX having played all the guitars on Bic Runga’s 11 x platinum debut album ‘Drive’. He has toured the world with many of New Zealand’s leading singer songwriter’s including Bic, Dave Dobbyn, Jan Hellriegel, Tim Finn and played support for international acts including Radiohead, Bryan Adams and Jeff Buckley. Bass player Brett Wells is a Chartered Director and Executive Management Professional with over 25 years operations experience in Webb Group (incorporating the Rockshop; KBB Music; wholesale; service and logistics) and foundation member of the Board. -

Presidential Documents Vol

42215 Federal Register Presidential Documents Vol. 81, No. 125 Wednesday, June 29, 2016 Title 3— Proclamation 9465 of June 24, 2016 The President Establishment of the Stonewall National Monument By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation Christopher Park, a historic community park located immediately across the street from the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City (City), is a place for the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community to assemble for marches and parades, expres- sions of grief and anger, and celebrations of victory and joy. It played a key role in the events often referred to as the Stonewall Uprising or Rebellion, and has served as an important site for the LGBT community both before and after those events. As one of the only public open spaces serving Greenwich Village west of 6th Avenue, Christopher Park has long been central to the life of the neighborhood and to its identity as an LGBT-friendly community. The park was created after a large fire in 1835 devastated an overcrowded tenement on the site. Neighborhood residents persuaded the City to condemn the approximately 0.12-acre triangle for public open space in 1837. By the 1960s, Christopher Park had become a popular destination for LGBT youth, many of whom had run away from or been kicked out of their homes. These youth and others who had been similarly oppressed felt they had little to lose when the community clashed with the police during the Stone- wall Uprising. In the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, a riot broke out in response to a police raid on the Stonewall Inn, at the time one of the City’s best known LGBT bars. -

Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century

The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century By Megan Marie Adams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair Professor Richard Candida-Smith Professor Kim Voss Fall 2012 1 Abstract The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century by Megan Marie Adams Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair My dissertation uncovers a history of labor insurgency and civil rights activism organized by the lowest-ranking members of the Chicago police. From 1950 to 1984, dissenting police throughout the city reinvented themselves as protesters, workers, and politicians. Part of an emerging police labor movement, Chicago’s police embodied a larger story where, in an era of “law and order” politics, cities and police departments lost control of their police officers. My research shows how the collective action and political agendas of the Chicago police undermined the city’s Democratic machine and unionized an unlikely group of workers during labor’s steep decline. On the other hand, they both perpetuated and protested against racial inequalities in the city. To reconstruct the political realities and working lives of the Chicago police, the dissertation draws extensively from new and unprocessed archival sources, including aldermanic papers, records of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, and previously unused collections documenting police rituals and subcultures. -

ACLU Facial Recognition–Jeffrey.Dalessio@Eastlongmeadowma

Thursday, May 7, 2020 at 1:00:56 PM Eastern Daylight Time Subject: IACP's The Lead: US A1orney General: Police Officers Deserve Respect, Support. Date: Monday, December 23, 2019 at 7:48:58 AM Eastern Standard Time From: The IACP To: jeff[email protected] If you are unable to see the message or images below, click here to view Please add us to your address book GreeWngs Jeffrey Dalessio Monday, December 23, 2019 POLICING & POLICY US AHorney General: Police Officers Deserve Respect, Support In an op-ed for the New York Post (12/16) , US A1orney General William barr writes, “Serving as a cop in America is harder than ever – and it comes down to respect. A deficit of respect for the men and women in blue who daily put their lives on the line for the rest of us is hurWng recruitment and retenWon and placing communiWes at risk.” barr adds, “There is no tougher job in the country than serving as a law-enforcement officer. Every morning, officers across the country get up, kiss their loved ones and put on their protecWve vests. They head out on patrol never knowing what threats and trials they will face. And their families endure restless nights, so we can sleep peacefully.” Policing “is only geng harder,” but “it’s uniquely rewarding. Law enforcement is a noble calling, and we are fortunate that there are sWll men and women of character willing to serve selflessly so that their fellow ciWzens can live securely.” barr argues that “without a serious focus on officer retenWon and recruitment, including a renewed appreciaWon for our men and women in blue, there won’t be enough police officers to protect us,” and “support for officers, at a minimum, means adequate funding. -

Covid 19 Support and Information for Parents Kia Ora Koutou

Covid 19 Support and Information for Parents Kia ora koutou I have provided some information to support our parents at this time. Please see the information below which may be of help to you. 1. Helping students stay safer online from home As you know, children's online safety is important. At school, Network for Learning (N4L) helps keep your students safe from the bad side of the internet. During lockdown, the students' place of learning shifts to their home. So N4L has worked out a way to help parents keep their children safely connected at home. FREE N4L safety filter for all students We've set up a safety filter that parents can set up on their child's learning devices from home. Just go to switchonsafety.co.nz to find clear instructions on how to do this. The free N4L safety filter (by global cyber-security leader, Akamai) blocks websites containing known cyber threats like phishing scams, malicious content and viruses, while also protecting children from content deemed the worst of the web (like adult sites). It is an extension of one of the many safety and security services we have in place at schools and is a valuable layer of protection to help keep children safe online. How does it work? Once a child's device is set up, all internet search requests will go through the safety filter which checks if the website they are trying to visit is safe before allowing access. If it's a website that's known to be unsafe, then it will be blocked. -

You Are Known by the Company You Keep

You Are Known By The Company You Keep , “ A friend through business is a friend indeed” Sir Len Southward May I introduce you to some of my friends…. I am delighted to introduce you to some of the many wonderful people I have had the Honour of working with over the years, people who have made music their livelihood and delighted the hearts of millions around the world. You too have joined the famous and those with prestige by employing the services of Allen Birchler, Piano Tuner to the Regent on Broadway. You are welcome to make my friends, yours. Allen C Birchler. A graduate of the famous Julliard School, Nina Tichman (piano) has won many prestigious competitions and appears as a soloist with orchestras and recital the world over. Xyrion Trio "At the risk of running out of superlatives, it was complex, vibrant dangerously inspired and just plain, absolutely brilliant" Otago Daily Times Bringing together three of Germany’s finest musicians - Nina Tichman, Ida Bieler and Maria Kliegel - the Xyrion Trio (pronounced ‘Ziri-on’, like ‘Xena, Warrior Princess’) tour for Chamber Music New Zealand in October. A graduate of the famous Julliard School, Nina Tichman (piano) has won many prestigious competitions and appears as a soloist with orchestras and recital the world over. In 2004 Nina was invited to perform for the President of Germany. Ida Bieler (violin), for many years a member of the Melos Quartet, is in demand as a teacher and a judge at international masterclasses and competitions. Maria Kliegel is one of the leading cellists of the 21st Century. -

Ecri Report on the Netherlands

CRI(2013)39 ECRI REPORT ON THE NETHERLANDS (fourth monitoring cycle) Adopted on 20 June 2013 Published on 15 October 2013 ECRI Secretariat Directorate General II - Democracy Council of Europe F-67075 STRASBOURG Cedex Tel.: + 33 (0) 388 41 29 64 Fax: + 33 (0) 388 41 39 87 E-mail: [email protected] www.coe.int/ecri TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................................ 5 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................... 7 FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................... 11 I. EXISTENCE AND APPLICATION OF LEGAL PROVISIONS ........................ 11 INTERNATIONAL LEGAL INSTRUMENTS ................................................................. 11 CRIMINAL LAW PROVISIONS ................................................................................ 11 CIVIL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW PROVISIONS ...................................................... 18 ANTI-DISCRIMINATION BODIES AND POLICY .......................................................... 20 - THE NATIONAL OMBUDSMAN ...................................................................... 20 - LOCAL ANTI-DISCRIMINATION BUREAUS AND ART. 1 ..................................... 20 - NETHERLANDS INSTITUTE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (NIHR)................................ 22 - THE NATIONAL CONSULTATION PLATFORM ON MINORITIES .......................... 23 - ANTI-DISCRIMINATION POLICY .................................................................... -

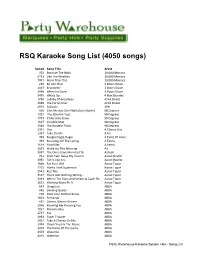

Karaoke 4050 Song List

RSQ Karaoke Song List (4050 songs) Song# Song Title Artist 302 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 2133 Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs 1901 More Than This 10,000 Maniacs 285 Be Like That 3 Doors Down 2047 Kryptonite 3 Doors Down 3446 When Im Gone 3 Doors Down 3435 Whats Up 4 Non Blondes 1798 Lullaby Of Broadway 42nd Street 3089 The Partys Over 42nd Street 2879 Sukiyaki 4PM 866 Give Me Just One Night (Una Noche) 98 Degrees 1201 I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees 1373 If She Only Knew 98 Degrees 1687 Invisible Man 98 Degrees 3046 The Hardest Thing 98 Degrees 2331 One A Chorus Line 2937 Take On Me A Ha 393 Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste Of Hone 409 Bouncing Off The Ceiling A Teens 1619 Floorfiller A Teens 3563 Woke Up This Morning A3 3087 The One I Gave My Heart To Aaliyah 762 Dont Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville 2951 Tell It Like It Is Aaron Neville 1646 For You I Will Aaron Tippin 1103 Honky Tonk Superman Aaron Tippin 2042 Kiss This Aaron Tippin 3147 There Aint Nothing Wrong... Aaron Tippin 3483 Where The Stars And Stripes & Eagle Fly Aaron Tippin 3572 Working Mans Ph.D. Aaron Tippin 543 Chiquitita ABBA 652 Dancing Queen ABBA 720 Does Your Mother Know ABBA 1603 Fernando ABBA 851 Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA 2046 Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA 1821 Mamma Mia ABBA 2787 Sos ABBA 2893 Super Trouper ABBA 2921 Take A Chance On Me ABBA 2974 Thank You For The Music ABBA 3078 The Name Of The Game ABBA 3370 Waterloo ABBA 4018 Waterloo ABBA Party Warehouse Karaoke System Hire - Song List Song# Song Title Artist 1660 Four Leaf Clover Abra Moore 2840 Stiff Upper Lip -

Mattersofsubstance

Mattersof Substance. october 2017 Volume 28 Issue No.3 www.drugfoundation.org.nz We should have known The recent extraordinary spate of 20 deaths linked with synthetic cannabinoid use could have been avoided. The warning signs were there, but who was listening? CONTENts FEATURE: TUHOETANGA We should 16 have known FEATURE: ENLIGHTENMENT AT THE COVER: How New Zealand failed END OF THE MAZE to spot the synthetics crisis NZ 02 NEWS $ 20 COVER 06 STORY 3M FEATURES Become 14 16 20 22 a member Without warning Tühoetanga Enlightenment at the Public mood swing: An early warning system As Tühoe inch closer to end of the maze Have Asia’s brutal The New Zealand Drug Foundation has could save lives. Rob Zorn mana motuhake – self- World-leading drug policy drug wars hit a nerve? been at the heart of major alcohol and compares a couple of determination – a Drug experts plus an enthusiastic Mangai Balasegaram asks other drug policy debates for over 20 years. international examples Foundation hui in Rüätoki crowd of advocates, whether public outrage During that time, we have demonstrated that might work here. touched on what that politicians, clinicians could mark a turning point a strong commitment to advocating could mean for healthcare. and activists equals hope in Rodrigo Duterte’s bloody policies and practices based on the for change. War on Drugs. best evidence available. You can help us. A key strength of the Drug Foundation lies in its diverse membership base. As a member of the Drug Foundation, REGULARS you will receive information about major alcohol and other drug policy challenges. -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON