Journal of African Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Infrastructure Construction Dynamics Causes of Delays and Its Effects on Pedestrians' Safety in Ghana.Pdf

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA INSTITUTE OF STATISTICAL, SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH ROAD INFRASTRUCTURE CONSTRUCTION DYNAMICS: CAUSES OF DELAYS AND ITS EFFECTS ON PEDESTRIANS’ SAFETY IN GHANA BY SERWAA KUFFOUR ACHEAMPONG (10479583) THIS DISSERTATION IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES JULY, 2019 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I thereby declare that this research is the result of my own field work towards the completion of my Master of Arts degree in Development Studies and that to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any degree of the University or elsewhere, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. ACHEAMPONG, SERWAA KUFFOUR (10479583) 22 / 11/ 2019 CANDIDATE’S FULL NAME (ID) Signature Date Certified By DR. ANDREW AGYEI-HOLMES 22 – 11 - 2019 (SUPERVISOR) Signature Date ii | P a g e University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ABSTRACT The purpose of the study is to research into road infrastructure construction dynamics with focus on causes of delays and its effects on pedestrians’ safety in Ghana. Using a comparative analysis to examine dynamism in road infrastructure construction delays and its effects on pedestrians’ safety, Lapaz (N1) and Madina (N4) highways in Accra Metro and La- Nkwantanag Madina Municipality respectively were selected for the study because N1 was successfully completed on time while N4 is suffering delay. -

Preparatory Survey on Eastern Corridor Development Project in the Republic of Ghana

IN THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA EASTERN CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PREPARATORY SURVEY ON MINISTRY OF ROADS AND HIGHWAYS (MRH) REPUBLIC OF GHANA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON EASTERN CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA FINAL REPORT FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2013 JANUARY 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CENTRAL CONSULTANT INC. PADECO CO., LTD. EI CR(3) 13-002 IN THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA EASTERN CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT PREPARATORY SURVEY ON MINISTRY OF ROADS AND HIGHWAYS (MRH) REPUBLIC OF GHANA PREPARATORY SURVEY ON EASTERN CORRIDOR DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IN THE REPUBLIC OF GHANA FINAL REPORT FINAL REPORT JANUARY 2013 JANUARY 2013 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) CENTRAL CONSULTANT INC. PADECO CO., LTD. Exchange Rate US$ 1 = GHS 1.51 = JPY 78.2 October 2012 PREFACE Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) decided to conduct the Preparatory Survey on Eastern Corridor Development Project in the Republic of Ghana and entrusted the study to Central Consultant Inc. and PADECO Co., Ltd.. The team held discussions with officials of the Government of the Republic of Ghana and conducted a feasibility study on the construction of the Eastern Corridor from March to October 2012. After returning to Japan, the team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will promote the project and enhance friendly relationship between our two countries. Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the Government of the Republic of Ghana for their tremendous cooperation with the study. January 2013 Kazunori MIURA Director General Economic Infrastructure Department Japan International Cooperation Agency Bird’s Eye View of the New Bridge across the Volta River Eye Level View of the New Bridge across the Volta River SUMMARY Preparatory Survey on Eastern Corridor Development Project in the Republic of Ghana Final Report Summary SUMMARY 1. -

Argo Set for Take-Off

ATRATR July July 2018 2018 CW - Cover_Layout Front_cover.qxd 1 27/06/2018 26/06/2018 11:11 07:58 Page Page 2 1 www.africanreview.com Europe €10, Ghana C1.8, Kenya Ksh200, Nigeria N330, South Africa R25, UK £7, USA $12 TRANSPORTTRANSPORT POWERPOWER CONSTRUCTION MINING HeavyHeavy andand lightlight truck truck sales sales CountriesCountries revise revise tariffs tariffs to to reduce reduce Which countries import the most Mobile energy solutions in continuecontinue toto dominatedominate regionregion P24 P24 barriersbarriers to to mini-grids mini-grids P38 P38 machinery from China? P46 mining P56 JULY 2018 African Review of Business and Technology P22 AIR CARGO SET FOR TAKE-OFF The region experiences fastest air cargo growth in 18 months July July 2018 P50 CAMEROON’S SIGNAL TO THE WORLD Douala Grand Mall to be Central Africa’s largest shopping complex to mini-grids P30 ANNUAL GENSET REVIEW Diesel genset imports increase by 25 per cent in the first quarter of 2018 Volume 54 Volume Number 6 P16 www.africanreview.com “In Africa, there needs to be more focus on infrastructure development that will YEARS support sustainable cities” Herbert Phahlane, director, traffic and SERVING BUSINESS IN 54AFRICA SINCE 1964 transportation, WSP, commercial civils, Africa ATR July 2018 Coverwrap Reverse_Layout 1 26/06/2018 07:52 Page 1 ATRJuly2018-Cover_Layout127/06/201811:11Page2 www.africanreview.com Europe €10, Ghana C1.8, Kenya Ksh200, Nigeria N330, South Africa R25, UK £7, USA $12 TRANSPORT POWER CONSTRUCTION MINING Heavy and light truck sales Countries revise -

100623 Iptghana Vol 07 Multicriteria Evaluation Manual

Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning Republic of Ghana Integrated Transport Plan for Ghana Volume 7: Multi-criteria Evaluation Manual Final Version June 2010 Financed by the 9th European Development Fund Service Contract N° 9 ACP GH019 In association with Egis Bceom International Executive Summary According to the Terms of Reference, the objective of this component of the Integrated Transport Plan (ITP) is to establish a methodology for carrying out economic, financial, social and environmental evaluation of projects. The revised work plan suggests to take into account in the evaluation process, additional aspects such as strategic access, inter and intra modal integration, and local access. At the long term planning level of the ITP, the projects under consideration are defined at identification or pre-feasibility stage. Therefore, the evaluation process cannot be as detailed as it would be at the feasibility/implementation stage. In general, the data used consists of secondary source data, although some primary specific survey data may be available (e.g. traffic counts and survey). Cost estimates are generally based on standard costs (e.g. costs per kilometer) since in-depth engineering studies are not yet carried out. The purpose of the evaluation carried out at long term planning level is to select the projects which best fit the goals of the national transport policy which are, in particular, to provide a sustainable, accessible, affordable, reliable, effective and efficient transport system. The proposed evaluation process described in this manual enables scoring the candidate projects according to a set of relevant criteria. The diagram below shows the positioning of this manual in the overall project planning and implementing process that encompasses the following steps: Long term planning is undertaken using two main tools: • The transport model is used to develop a model for transport demand and supply. -

Critical Success Factors (Csfs) of MIDA Compact I Road Transport Project in Ghana

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Pretoria / Johannesburg, South Africa, October 29 – November 1, 2018 Critical Success Factors (CSFs) of MIDA Compact I Road Transport Project in Ghana Amevi Acakpovi Electrical and Electronic Engineering Department Accra Technical University Accra, Ghana [email protected] Abena M. Adutwum 1Open University of Malaysia/ Accra Institute of Technology (AIT), Accra-North Accra, P.O.Box: AN19782, Accra, Ghana [email protected] Mathias Bennet Michael Electrical and Electronic Engineering Department Accra Technical University Accra, Ghana [email protected] Samuel Blay Amo Electrical and Electronic Engineering Department Accra Technical University Accra, Ghana [email protected] Anthony Deku Mechanical Engineering Department Accra Technical University Accra, Ghana [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this study is to provide insight into the critical success factors (CSFs) of a quasi-public institution in the delivery of projects, including the institutional structure of MiDA, processes and procedures affecting the successful implementation of the transport project under the MiDA Compact 1. In order to identify the critical success factors the study was planned and performed in two stages. The first stage of the approach was to subject the set of success factors identified in preliminary evaluation to expert group of respondents involved in the MiDA Compact 1 project. The second stage of the process was to subject the selected CSFs to full scale evaluation by expanding respondents to determine their relative importance. To determine the relative importance of the CSFs based on the expanded survey data, two statistical analysis, namely ranking and factor analysis were performed. -

Male Prioritization Over Girls' Education in the Gomoa.Pdf

University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA MALE PRIORITIZATION OVER GIRLS' EDUCATION IN THE GOMOA EAST DISTRICT OF GHANA CHRISTOPHER ADU-YEBOAH DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2019 University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION, WINNEBA MALE PRIORITIZATION OVER GIRLS' EDUCATION IN THE GOMOA EAST DISTRICT OF GHANA CHRISTOPHER ADU-YEBOAH A thesis in the Department of Social Studies Education, Faculty of Social Science, submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Social Studies Education) in the University of Education, Winneba JULY, 2019 University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh DECLARATION STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, Christopher Adu-Yeboah, declare that this thesis, with the exception of quotations and references contained in published works which have all been identified and duly acknowledged, is entirely my own original work, and it has not been submitted, either in part or whole, for another degree elsewhere. SIGNATURE: ...................................................... DATE:................................................................... SUPERVISORS’ DECLARATION We hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of this work was supervised in accordance with the guidelines for supervision of thesis as laid down by the University of Education, Winneba. Professor Yaw Ofosu Kusi (Principal Supervisor) Signature:………………….......................… Date:……………………………................... Dr. Lawrence Odumah (Co-supervisor) Signature:…………………............................. Date:…………………………………............. ii University of Education, Winneba http://ir.uew.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my profound gratitude to my principal supervisor, Professor Yaw Ofosu Kusi, Dean, Faculty of Social Science, University of Education, Winneba for not only guiding me throughout the thesis but also for making sure that I complete the thesis on schedule. -

Making Transport Climate Resilient Country Report: Ghana

World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Making Transport Climate Resilient Country Report: Ghana December 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized COWI A/S Parallelvej 2 DK-2800 Kongens Lyngby Denmark Tel +45 45 97 22 11 Fax +45 45 97 22 12 www.cowi.com World Bank Making Transport Climate Resilient Country Report: Ghana December 2010 Document no. P-70922A_04 Version 2 Date of issue 10 Dec 2010 Prepared ARBO, ABH, JOHR, MHO Checked KSP Approved KSP Making Transport Climate Resilient - Ghana Country Report i Table of Contents 0 Executive summary 1 1 Introduction and background 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Summary of conclusions 8 1.3 Engineering costs of climate change 13 1.4 Economic costs and benefits of adaption 15 1.5 The strategy forward for climate change adaption in the road sector 15 2 Climate risk scenarios for Ghana 17 2.1 Climate characteristics for Ghana 17 2.2 Emission scenarios and climate models 22 2.3 Climate change characteristics 26 2.4 Climate change for scenarios in this study 30 3 Ghana road network 45 3.1 Introduction 45 3.2 Current road assets in Ghana 50 4 Climate change impacts on road assets 55 4.1 Introduction 55 4.2 Temperature 55 4.3 Rain 57 4.4 Sea level rise 83 4.5 Nature and extent of climate impacts 86 4.6 National design standards in Ghana 94 4.7 Maintenance 94 5 Costs of climate change 101 5.1 Introduction 101 5.2 Current costs 101 5.3 Climate impact 102 O:\A000000\A002765\3_Pdoc\DOC\Ghana Report\2 - ver to WB dec 2010\MTCR Ghana_10 Dec 2010.docx ii Making -

George Walker Bush Motorway (N1), Accra

CHRISTIAN SERVICE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, KUMASI DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE SURVEILLANCE SYSTEM FOR THE POLICE CASE STUDY: GEORGE WALKER BUSH MOTORWAY (N1), ACCRA BAYOR CEPHAS KANYIRI TAYLOR ROBERT EBOW A THESIS PRESENTED TO CHRISTIAN SERVICE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF B. SC. COMPUTER SCIENCE JUNE, 2014 STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY We have read the university regulations relating to plagiarism and certify that this report is our own work and do not contain any unacknowledged work from any other source. We also declare that we have been under supervision for this report herein submitted. NAME SIGNATURE DATE BAYOR CEPHAS KANYIRI (10140954) ......………………… ………………..... TAYLOR ROBERT EBOW (10140855) ................................ ………………… SUPERVISOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that the preparation and presentation of the thesis were supervised in accordance with the guidelines on supervision laid down by Christian Service University College, Kumasi- Ghana. Certified by Dr. Thomas Yeboah (Mr.) …………………… ………………..... Supervisor Signature Date Dr. Thomas Yeboah (Mr.) …………………… ………………..... Head of Department, Computer Science Signature Date i DECLARATION We do hereby, declare that the dissertation entitled “Surveillance System for the Police on the George Walker Bush Motorway, Accra” is an authentic work developed by us BAYOR CEPHAS KANYIRI and TAYLOR ROBERT EBOW at Christian Service University College, under the guidance of Dr. Thomas Yeboah (Lecturer) and submitted as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a Degree. We also declare that, any contents incorporated in this dissertation have not been submitted in any form for the award in any university or elsewhere. It is a genuine record of the task we set out to accomplish. -

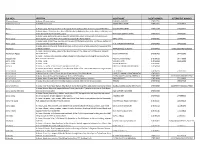

Sub-Area Location Agent Name Agent Number Alternative

SUB-AREA LOCATION AGENT NAME AGENT NUMBER ALTERNATIVE NUMBER 37 main station In Accra, 37 main station DORINDA AMARTEY 278794719 37 Military Station In 37 Military Station JOSEPH EBO DADZIE 278794811 271597614 Abeka In Accra-Lapaz, Flat Top junction on the Lapaz Achimota Road, 50m from the Lapaz MTN Office. MONAZ STATIONERY 278791074 276002699 In Accra, Lapaz, Meacham Hse. Annex, Mallam Abeka Highway, close to the Lapaz traffic light next Abeka to the Standard Chartered Bank, Lapaz. EB-ACCION (ABEKA LAPAZ) 278793109 244563361 In Accra-Lapaz, Adjacent Ecobank, opposite Lapaz Police depot, at Lapaz Circle to Accra main Abeka Lapaz trotro station and First Floor of the building opposite the Police Station GHFU LAPAZ 278789481 277440440 In Accra-Lapaz, Nii Boi Town junction, at the Lapaz traffic light, adjacent to Las Palmas Restaurant Abeka Lapaz and opposite the Lapaz Ecobank branch. M. B. MALBEN ENTERPRISE 278789405 244232030 In Accra, Ablekuma Fanmilk, Fanmilk junction, on the premise of Maame Soldier's house and 70m Ablekuma to Galary junction. TRIPPLE EAGLE SUSU ENT 278794422 0245819320/0276292813 In Accra, Ablekuma-Agape, close to the Giash School, at the Agape Lorry Station and adjacent Ablekumah-Agape Flash Pharmacy FLASH MARKETING 278790465 247755893 In Accra - Abossey okai, opposite Kofapa Enterprise, behind Former City Lights and close to the Abossey okai New Fortune Enterprise. POSITIVE MIND TOOLS 278794566 247778688 Accra Circle In Accra Circle VICTORIA HAYI 278794814 242960084 Accra Circle In Accra Circle JOSEPH BOABENG 278794815 -

Secondary City of Ningo-Prampram in the Greater Accra Region

GOOD GOVERNANCE AFRICA MINI STUDY REPORT BUILDING SUSTAINABLE SECONDARY CITIES: THE CASE OF NINGO-PRAMPAM CITY EXTENSION Written By: Kwadwo Ohene Sarfoh (PhD) Edward Teye Sarpong Kwame Boye BUILDING SUSTAINABLE SECONDARY CITIES: THE CASE OF NINGO-PRAMPAM CITY EXTENSION Published By Good Governance Africa – West Africa (GGA-WA) Edited By: Tina Asante-Apeatu Gifty Obeng Designed By: Hs Media Executive Director Tina Serwaa Asante-Apeatu Programs/M&E Manager Gifty Obeng Senior Research Officer Edward Teye Sarpong Project Assistant Akosua Sapaning Contributors to this Publication Kwadwo Ohene Sarfoh (PhD) Edward Teye Sarpong Kwame Boye About Good Governance Africa Founded in 2012, the Good Governance Africa is a registered Not for Profit Organization (NPO) with centers in Accra, Ghana covering Anglophone West Africa except for Nigeria which has an independent center in Lagos. For Southern Africa, GGA has centers in Johannesburg, South Africa and Harare, Zimbabwe. New centers have been opened at Goree Institute in Dakar, Senegal to cover Francophone West Africa and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia called the AU Centre. Good Governance Africa aims to promote good governance in Africa through applied research and critical debate (advocacy). Our publications include Africa in Fact, the African Survey and other projects. Research areas include local governance, land and natural resources, early childhood education and national security. GGA West Africa is also concerned with the promotion of local economic development, urban governance, right to information, justice and accountability, innovation, environmental sustainability (including climate change issues) and leadership. Opinions expressed, and definitions given in this publication without reference to any author or other authorities are those of the individual authors and not necessarily of Good Governance Africa. -

Chapter 3 Present Situation of the Transport System in the Study Area

CHAPTER 3 PRESENT SITUATION OF THE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE STUDY AREA Preparatory Survey on Eastern Corridor Development Project in the Republic of Ghana Final Report Chapter 3 Present Situation of Transport System in the Study Area Chapter 3 Present Situation of the Transport System in the Study Area 3.1 Present Situation of the Road Sub-sector 3.1.1 Policy and Programmes of the Road Sub-sector (1) National Transport Policy (NTP) The GoG prepared GPRS II in 2005 to attain Middle Income Status by 2015. In order not only to achieve the status but also to ensure continuously rising incomes, the GoG puts emphasis on poor people benefiting from the increased income generated by the country. Investment in transport infrastructure has a direct relation with poverty reduction, and so GPRS II highlights the importance of transport infrastructure for economic growth and poverty reduction. The National Transport Policy (NTP) was prepared as a transport infrastructure sector study to reach the goal of GPRS II, and is Ghana’s first comprehensive NTP. It defines aims such as: • To meet the needs of transport users • To underpin sectoral policies for trade, industry, agriculture, energy and tourism • To facilitate the provision of basic health and education services throughout the country • To support national growth and poverty reduction strategies for the sustainable development of Ghana as a whole Priorities in the transport infrastructure policy have been decided based on short-term imperatives, resulting in disharmonized development. For example, 99% of the budget for infrastructure including the road fund has been allocated to the road sub-sector for rapidly extending the road network7. -

Urbanisation in Ghana

Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The mandate of the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), like many other national statistical offices, includes data collection, compilation and analysis as well as dissemination of statistical information in an accessible and user-friendly manner. In order to satisfy the needs of users, GSS is required to analyse and interpret statistics in a form that makes it easily understood for people to appreciate the value of the statistical information. There is also the need to disseminate widely all the statistics produced by GSS so that all data users including potential data users can have access to it. Ghana, like many other developing countries, relies mainly on survey and population census data for planning at the national and the sub-national levels. Detailed analysis of such data provides users with a wealth of information for planning and policy formulation. Analysis of the 2010 Population and Housing Census data on topical issues, therefore, provides information for effective planning at all levels. Several reports, including six monographs, were prepared using the 2010 Census data and published in 2012 and 2013. The published reports from the census data was a collaborative effort between the GSS and Local consultants from research institutions and universities in Ghana with funding from the Government of Ghana and various Development Partners (DPs). In order to strengthen the report writing capacities of the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) and Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) which are engaged in population- related activities, professional staff of GSS and these MDAs were paired up with consultant writers to prepare the reports.