Closing the Door on Open Source: Can the General Public License Save Linux and Other Open Source Software?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SCO to Attack Validity of Linux Licence SCO's Strategy for Its Lawsuit Against IBM Could Destroy the Legal Foundation of Linux and Related Software

MENU ● US MUST READ: New Windows 10 feature could improve your battery life and stop that annoying fan noise, too SCO to attack validity of Linux licence SCO's strategy for its lawsuit against IBM could destroy the legal foundation of Linux and related software By Matthew Broersma | August 15, 2003 -- 13:50 GMT (06:50 PDT) | Topic: Government : UK SCO Group is planning to argue in its court battle against IBM that the General Public License (GPL) covering Linux and other open-source software is invalid, according to a report. SCO, owner of several key copyrights related to the Unix operating system, has been aggressively defending its intellectual property holdings connected to Unix System V, and filed a $3bn (£1.87bn) lawsuit against IBM earlier this year. The suit claims that IBM has committed trade-secret theft and breach of contract for allegedly copying proprietary Unix source code into its Linux-based products. IBM's defence will partly rest on the argument that SCO distributed its own version of Linux for many years, containing the allegedly infringing code, and that by this action effectively placed the code in question under the GPL. SCO is planning to respond that the GPL itself is invalid, SCO's lead attorney, Mark Heise of Boies Schiller & Flexner, told the Wall Street Journal in a report on Thursday. If SCO is successful, its lawsuit would undermine the legal basis for Linux and much other open-source software, although the open-source community has prepared an alternative licence that could be used by Linux if the GPL is invalidated. -

Utah State Bar No. 10060; Email: [email protected]) David R

WORKMAN | NYDEGGER A PROFESSIONAL CORPORATION Sterling A. Brennan (Utah State Bar No. 10060; Email: [email protected]) David R. Wright (Utah State Bar No. 5164; Email: [email protected]) Kirk R. Harris (Utah State Bar No. 10221; Email: [email protected]) Cara J. Baldwin (Utah State Bar No. 11863; Email: [email protected]) 1000 Eagle Gate Tower 60 E. South Temple Salt Lake City, UT 84111 Telephone: (801) 533-9800 Facsimile: (801) 328-1707 MORRISON & FOERSTER LLP Michael A. Jacobs (Admitted Pro Hac Vice; Email: [email protected]) Eric M. Acker (Admitted Pro Hac Vice; Email: [email protected]) Grant L. Kim (Admitted Pro Hac Vice; Email: [email protected]) Daniel P. Muino (Admitted Pro Hac Vice; Email: [email protected]) 425 Market Street San Francisco, CA 94105-2482 Telephone: (415) 268-7000 Facsimile: (415) 268-7522 Attorneys for Defendant and Counterclaim-Plaintiff Novell, Inc. IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF UTAH, CENTRAL DIVISION THE SCO GROUP, INC., a Delaware Case No. 2:04CV00139 corporation, NOVELL’S OPPOSITION TO SCO’S Plaintiff, RENEWED MOTION FOR JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF v. LAW OR A NEW TRIAL NOVELL, INC., a Delaware corporation, Judge Ted Stewart Defendant. AND RELATED COUNTERCLAIMS. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 II. SCO IS NOT ENTITLED TO JUDGMENT AS A MATTER OF LAW .........................3 A. Legal Standard........................................................................................................3 B. The Jury’s Verdict That the Amended Asset Purchase Agreement Did Not Transfer Copyright Ownership Is Reasonable and Supported by the Evidence.................................................................................................................3 1. The Asset Purchase Agreement Established That Santa Cruz Was Novell’s Agent. -

MEMORANDUM in Support Re 657 MOTION for Daubert Hearing To

SCO Grp v. Novell Inc Doc. 658 Att. 1 EXHIBIT A Dockets.Justia.com Brent O. Hatch (5715) Stephen N. Zack (admitted pro hac vice) Mark F. James (5295) BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP HATCH, JAMES & DODGE, PC Bank ofAmerica Tower - Suite 2800 10 West Broadway, Suite 400 100 Southeast Second Street Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Miami, Florida 33131 Telephone: (801) 363-6363 Telephone: (305) 539-8400 Facsimile: (801) 363-6666 Facsimile: (305) 539-1307 David Boies (admitted pro hac vice) Robert Silver (admitted pro hac vice) Stuart Singer (admitted pro hac vice) Edward Normand (admitted pro hac vice) BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP BOIES, SCHILLER & FLEXNER LLP 401 East Las Olas Blvd. 333 Main Street Suite 1200 Armonk, New York 10504 Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301 Telephone: (914) 749-8200 Telephone: (954) 356-0011 Facsimile: (914) 749-8300 Facsimile: (954) 356-0022 Devan V. Padmanabhan (admitted pro hac vice) DORSEY & WHITNEY LLP 50 South Sixth Street, Suite 1500 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55402 Telephone: (612) 340-2600 Facsimile: (612) 340-2868 Attorneysfor Plaintiff, The SeQ Group, Inc. IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF UTAH THE SCO GROUP, INC., EXPERT REPORT AND a Delaware corporation, DECLARATION OF GARY PISANO Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, Civil No.: 2:04CV00139 vs. Judge Dale A. Kimball Magistrate Brooke C. Wells NOVELL, INC., a Delaware corporation, Defendant/Counterclaim-Plaintiff. DECLARAnON AND EXPERT REPORT OF GARY PISANO IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 1 I. ASSIGNMENT 2 II. QUALIFICATIONS 3 III. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS 4 IV. BACKGROUND 5 A. The Evolution ofUNIX 5 B. SCO's Relationship with UNIX 7 C. -

SCO's Big Legal Gun Takes Aim Attorney Mark Heise Is Leading the Company's Battle Against IBM--A Legal Case He Says May Redefine the Direction of the Software Industry

New In Dresses Ad by URBAN OUTFITTERS See More Johnson & Johnson vaccine Mortal Kombat review Quiplash is free AirTags Falcon and Winter Soldier finale COVID-19 BEST REVIEWS NEWS HOW TO HOME CARS DEALS 5G J O I N / S I G N I N SCO's big legal gun takes aim Attorney Mark Heise is leading the company's battle against IBM--a legal case he says may redefine the direction of the software industry. Aug. 21, 2003 12:32 p.m. PT 0 Instead of talking up new products, SCO Group executives devoted the bulk of their presentations at this week's SCO Forum to the fight against Linux. And for good reason. The company sued IBM in March, saying it illegally contributed some of SCO's licensed Unix code to Linux. Since then, SCO has been making a major business out of intellectual property enforcement, which happens to be the company's fastest-growing revenue generator. SCO's lawsuit has excited no small degree of controversy. Critics say the company is trying to shake down Linux users and that it does not have any legal basis for its claims. So in a bid to clarify its case both to customers and detractors, the company showed the disputed code to some attendees at the SCO Forum, its annual user conference that took place this week in Las Vegas. But that step did anything but lower the temperature. Shortly after making the offer to let outsiders examine the code, members of the Linux community blasted SCO, saying the code was originally covered under a public license that allows it to be shared. -

TECHNOLOGY; Software Company's Battle Over Unix Produces Profit

https://www.nytimes.com/2003/05/29/business/technology-software- company-s-battle-over-unix-produces-profit.html TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY; Software Company's Battle Over Unix Produces Profit By Steve Lohr May 29, 2003 A recent campaign of litigation and warnings by a Utah software marketer against companies that use Linux has helped make the company profitable for the first time ever, it said yesterday. Less than three months ago, the company, the SCO Group, started what has become an escalating skirmish in the software industry by asserting that its rights to the Unix operating system were being widely violated by computer companies that back Linux, and perhaps by the thousands of companies that use Linux. The latest volleys came yesterday. Novell, which sold the Unix business to SCO in 1995, contended that it had not passed on the intellectual property rights to the system in the sale to SCO, a contention SCO disputes. And a German software group, Linuxtag, threatened to sue SCO unless it stopped its anti-Linux campaign. Linux, which is distributed free, is a close relative of Unix, which was originally developed at AT&T Bell Labs in the late 1960's. But the commercial rights to Unix, after a series of transactions, are now held by SCO, which has licensed that underlying technology to other companies, including I.B.M., Sun Microsystems and Hewlett-Packard, to develop their own flavors of Unix. There was good news yesterday for SCO, as well. The company reported a quarterly profit of $4.5 million on revenue of $21.4 million. -

SCO GROUP V. IBM: the FUTURE of OPEN-SOURCE SOFTWARE

SCO GROUP v. IBM: THE FUTURE OF OPEN-SOURCE SOFTWARE Kerry D. Goettsch* I. INTRODUCTION What started as a contract dispute between Caldera Systems, Inc. (“Caldera”), and International Business Machines Corporation (“IBM”) has blossomed into a massive legal effort with the potential to change the entire open-source software movement.1 Developers of open-source software, which is largely defined by the success of the Linux operating system, had envisioned bringing reliable software to everyone at little or no cost. But legal action may derail that vision. Caldera, which now operates as the SCO Group (“SCO”), claims that IBM illegally introduced parts of its copyrighted Unix software into open-source Linux, thus creating copyright infringers out of every Linux distributor, developer, and user. SCO’s legal actions have recently expanded beyond its suit against IBM, and it is now threatening to sue companies that use Linux without paying a Unix licensing fee. Given the proliferation of Linux throughout the business world, the outcome of this case could have a wide-ranging impact. At a minimum, this case will delineate the future course for open-source software. II. LINUX BACKGROUND Linux is an operating system designed to function like the Unix operating system, while at the same time avoiding some of the technical and legal problems that Unix presented.2 The primary “problem” with Unix concerns its ownership, which means that its use, distribution, and * J.D., University of Illinois College of Law, 2004. 1. For a general statement describing the open-source movement, see Free Software Foundation, Inc., at http://www.gnu.org/fsf/fsf.html (last visited Feb. -

Plaintiff, V. I

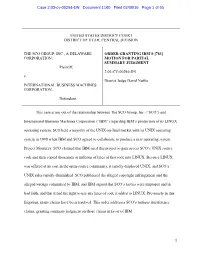

Case 2:03-cv-00294-DN Document 1160 Filed 02/08/16 Page 1 of 65 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF UTAH, CENTRAL DIVISION THE SCO GROUP, INC., A DELAWARE ORDER GRANTING IBM’S [783] CORPORATION; MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT Plaintiff, 2:03-CV-00294-DN v. District Judge David Nuffer INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS MACHINES CORPORATION, Defendant. This case arises out of the relationship between The SCO Group, Inc. (“SCO”) and International Business Machines Corporation (“IBM”) regarding IBM’s production of its LINUX operating system. SCO held a majority of the UNIX-on-Intel market with its UNIX operating system in 1998 when IBM and SCO agreed to collaborate to produce a new operating system, Project Monterey. SCO claimed that IBM used this project to gain access SCO’s UNIX source code and then copied thousands or millions of lines of that code into LINUX. Because LINUX was offered at no cost in the open-source community, it rapidly displaced UNIX, and SCO’s UNIX sales rapidly diminished. SCO publicized the alleged copyright infringement and the alleged wrongs committed by IBM, and IBM argued that SCO’s tactics were improper and in bad faith, and that it had the right to use any lines of code it added to LINUX. Previously in this litigation, many claims have been resolved. This order addresses SCO’s tortious interference claims, granting summary judgment on those claims in favor of IBM. 1 Case 2:03-cv-00294-DN Document 1160 Filed 02/08/16 Page 2 of 65 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... -

How Open Is Future

How Open is the Future? Marleen Wynants & Jan Cornelis (Eds) How Open is the Future? Economic, Social & Cultural Scenarios inspired by Free & Open-Source Software The contents of this book do not reflect the views of the VUB, VUBPRESS or the editors, and are entirely the responsibility of the authors alone. Cover design: Dani Elskens Book design: Boudewijn Bardyn Printed in Belgium by Schaubroeck, Nazareth 2005 VUB Brussels University Press Waversesteenweg 1077, 1160 Brussels, Belgium Fax + 32 2 6292694 e-mail: [email protected] www.vubpress.be ISBN 90-5487-378-7 NUR 740 D / 2005 / 1885 / 01 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/be/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbott Way, Stanford, California 94305, USA. There is a human-readable summary of the Legal Code (the full license) available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/be/legalcode.nl. Foreword & Acknowledgements This volume offers a series of articles ranging from the origins of free and open-source software to future social, economic and cultural perspectives inspired by the free and open-source spirit. A complete version of How Open is the Future? is available under a Creative Commons licence at http://crosstalks.vub.ac.be. How Open is the Future? is also available as printed matter, as you can experience at this moment. The topic of free and open-source software emerged from the initiative by Professor Dirk Vermeir of the Computer Science Department of the VUB – Vrije Universiteit Brussel – to award Richard Stallman an honorary doctorate from the VUB. -

Update on SCO Linux Litigation

NCLUG : 19.April.2005 Update on SCO Linux Litigation T.Michael Turney Open Source Ambassador Copyright 2005 Tools Made Tough SCO Linux Litigation Agenda • Review Timeline • Review SCO’s claims against IBM • Review SCO money trail and MS • Review SCO letter to Congress • Review Other, related lawsuits • Closing Thoughts • Most of research comes from Computer World Copyright 2005 Tools Made Tough SCO Linux Litigation Timeline 23.January.2003 SCO to enforce its IP in Linux world 7.March.2003 SCO sues IBM for $1B in IP fight 19.May.2003 Users Outraged as SCO stakes Linux Legal Claim Linux Vendors Reject SCO’s Legal Claims SCO confirms Microsoft has licensed its Unix technology 23.May.2003 SCO’s licensing deal with Microsoft raises user doubts 26.May.2003 Critics Question Motives in Microsoft/SCO Deal Copyright 2005 Tools Made Tough SCO Linux Litigation Timeline 2 26.May.2003 SCO’s Stock Plot 28.May.2003 Novel calls on SCO to prove allegations about Linux 4.June.2003 SCO hit by legal action in Germany 10.June.2003 SCO shows Linux code to analysts 16.June.2003 Analysts Say Evidence May Support SCO Case SCO pulls IBM’s AIX license in Unix dispute 10.July.2003 Open-source experts critique SCO lawsuit against IBM Copyright 2005 Tools Made Tough SCO Linux Litigation Timeline 3 28.July.2003 SCO’s Shell Game 4.August.2003 Red Hat fires back at SCO in Linux fight 11.August.2003 SCO gets first licensee for Unix IP software license 26.August.2003 SCO web site knocked out for three days 3.September.2003 SCO fined $10,800 in Germany for Linux claims 10.September.2003 -

Presentation, As Well As Links to Related Sites, Are At

Open Source: Theory and Practice John Ackermann [email protected] Copyright 2003 NCR Corporation What is Open Source? • An evolution of “Free Software” – “Free” refers to freedom, not price – The Free Software Foundation and its GNU (Gnu’s Not Unix) project are keepers of the flame • Open Source is a parallel, but more pragmatic, philosophy – Free software purists see Open Source proponents as fallen brethren – Free Software is Open Source, but not necessarily the reverse – New term is “Free and Open Source Software” (“FOSS”) 03/15/04 © 2003 NCR Corporation 2 The Open Source Development Model • Development in the bazaar, not the cathedral – The communication and distribution channel is the Internet – Development group is typically open – Rapid release of new versions – Open, public and ongoing testing 03/15/04 © 2003 NCR Corporation 3 Why is Open Source Important? • Open Source was an important part of the Internet from the beginning, but the outside world didn't notice • GNU/Linux made the world sit up and take notice – GNU developed most of the pieces of a free clone of the Unix operating environment – Linus Torvalds started Linux development as a hobby project, but it just grew... – The Linux kernel plus GNU tools result in a complete, free, alternative to commercial Unix 03/15/04 © 2003 NCR Corporation 4 The Linux Revolution • GNU/Linux is Free and Open Source Software licensed under the GPL (more on that later) • Major vendor support – IBM, HP, Sun, HP(Compaq (Digital)) – Oracle, Informix, SAP, SAS... • The only thing that Micro$oft -

EXHIBIT a 305 402-2854 Froi: Daniel Lampert To: Darl Mcbride Page 2 of 25 2007.10-2005:35:54 (GMT)

EXHIBIT A 305 402-2854 Froi: Daniel Lampert To: darl mcbride Page 2 of 25 2007.10-2005:35:54 (GMT) TIE SCO GROUP, INC. Term Sheet Tlús Term Sheet sets forth ceitain key telmS of a possible 11'I1Sactiol1 (a 7a:msactton ") beteen the Panies (dened below). 11Ûs Tel71 Sheet is not a definitive list of all of Purchaser's requirements in connection with a Transaction. 'fiis Term Sheet shalll10J be binding upon the Partiès wiless and witif approved in a final order of the Bankruptcy Court, which is in for11 and substance acceptable to each of them. Purchasr: A newly-fonned entity ("Purchaser")affliated with one or more fWids managed by JOD Management Corp. d/b/a York Cav¡ra Management, a Delaware corpration. 1 Seller: The SeD Group, Inc., and its direct or indirect i subsidiaries using the Transferred Assets (collectively, ! "Seller"; and toe.etlier with tle Puchaser, the "Paries"). Avaiabinty of Funds: Purchaser has cash available on hand or will at the closing of the Transaction (the "Closing") have fimi financing commitments sufcient to pay the Purchase - Price. Transferred Asts: Except for the Excluded As-sets, the Seller wm sell, assign, transfer and convey to Purchaser all right, title and interest in and to the assets, propertes and rights of Seller used or useful in connection with the operation of the SCO Unix Business of Seller as conducted in the past. present or proposed to be conducted, tangible and intangible, pursut to Sectio11363 of the Uiuted States Bankptcy Code (the "Transferred Assets"). The Transferred Assets shall include, -

Groklaw Shuts Down Award-Winning, Software Freedom-Defending Legal Site to Close Over Privacy Fears

This ISSUE: Ubuntu Edge War games GPL violation Android arguments BIG BROTHER Groklaw shuts down Award-winning, software freedom-defending legal site to close over privacy fears. roklaw, the legal site set up to US out or to the US in, but really fight the protracted SCO vs anywhere. You don’t expect a stranger GIBM case (see boxout, below) to read your private communications to has folded after 10 years of award- a friend. And once you know they can, winning campaigning journalism. The what is there to say? Constricted and site’s founder, Pamela Jones, cited fears distracted … That’s how I feel.” that she would not be able to protect the identity of sources in the light of Thanks for all the fishes recent revelations over email security. Jones, a paralegal by training, set up Writing in the site’s last post, Jones Groklaw to bridge the gap in said: “The owner of Lavabit tells us that understanding between the worlds of he’s stopped using email and if we knew the programmer and the courtroom. what he knew, we’d stop too. There is no Although it was originally intended to way to do Groklaw without email. provide clarity over the SCO vs IBM legal Therein lies the conundrum. fight, Groklaw also helped other legal “I hope that makes it clear why I cases with implications for free software, can’t continue. There is now no shield including Oracle vs Google, Microsoft vs Groklaw spoke rather than comply with a demand that from forced exposure. Nothing in that Motorola and Apple vs just about truth to power, it be given access to its users’ email parenthetical thought list is terrorism- everyone in the world.