Kenya 3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pollution of Groundwater in the Coastal Kwale District, Kenya

Sustainability of Water Resources under Increasing Uncertainty (Proceedings of the Rabat Symposium S1, April 1997). IAHS Publ. no. 240, 1997. 287 Pollution of groundwater in the coastal Kwale District, Kenya MWAKIO P. TOLE School of Environmental Studies, Moi University, PO Box 3900, Eldoret, Kenya Abstract Groundwater is a "last-resort" source of domestic water supply at the Kenyan coast because of the scarcity of surface water sources. NGOs, the Kenya Government, and international aid organizations have promoted the drilling of shallow boreholes from which water can be pumped using hand- operated pumps that are easy to maintain and repair. The shallow nature and the location of the boreholes in the midst of dense population settlements have made these boreholes susceptible to contamination from septic tanks and pit latrines. Thirteen percent of boreholes studied were contaminated with E. coli, compared to 30% of natural springs and 69% of open wells. Areas underlain by coral limestones show contamination from greater distances (up to 150 m away) compared to areas underlain by sandstones (up to 120 m). Overpumping of the groundwater has also resulted in encroachment of sea water into the coastal aquifers. The 200 ppm CI iso-line appears to be moving increasingly landwards. Sea level rise is expected to compound this problem. There is therefore an urgent need to formulate strategies to protect coastal aquifers from human and sea water contamination. INTRODUCTION The Government of Kenya and several nongovernmental organizations have long recog nized the need to make water more easily accessible to the people in order to improve sanitary conditions, as well as to reduce the time people spend searching for water, so that time can be freed for other productive economic and leisure activities. -

Notes on Provincial Consultative Mtg., Central, Nyeri

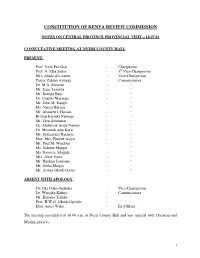

CONSTITUTION OF KENYA REVIEW COMMISSION NOTES ON CENTRAL PROVINCE PROVINCIAL VISIT – 18.07.01 CONSULTATIVE MEETING AT NYERI COUNTY HALL PRESENT: Prof. Yash Pal Ghai - Chairperson Prof. A. Idha Salim - 1st Vice-Chairperson Mrs. Abida Ali-Aroni - Vice-Chairperson Pastor Zablon Ayonga - Commissioner Dr. M.A. Swazuri - “ Mr. Isaac Lenaola - “ Mr. Riunga Raiji - “ Dr. Charles Maranga - “ Mr. John M. Kangu - “ Ms. Nancy Baraza - “ Mr. Ahamed I. Hassan - “ Bishop Kariuki Njoroge - “ Mr. Zein Abubakar - “ Dr. Abdirizak Arale Nunow - “ Dr. Mosonik arap Korir - “ Mr. Domiziano Ratanya - “ Hon. Mrs. Phoebe Asiyo - “ Mr. Paul M. Wambua - “ Ms. Salome Muigai - “ Ms. Kavetsa Adagala - “ Mrs. Alice Yano - “ Mr. Ibrahim Lethome - “ Mr. Githu Muigai - “ Mr. Arthur Okoth-Owiro - “ ABSENT WITH APOLOGY: Dr. Oki Ooko Ombaka - Vice-Chairperson Dr. Wanjiku Kabira - Commissioner Mr. Keriako Tobiko - “ Prof. H.W.O. Okoth-Ogendo - “ Hon. Amos Wako - Ex-Officio The meeting assembled at 10.00 a.m. at Nyeri County Hall and was opened with Christian and Muslim prayers. 1 The Deputy PC welcomed the Commissioners to Nyeri. The Commissioners introduced themselves and the participants also introduced themselves and included representatives from Mt. Kenya Law Society, Shelter Women of Kenya, Supkem, Safina, Sustainable Empowerment and Agricultural Network, Citizen Small and Medium Industries of Kenya, Build Kenya, Maendeleo ya Wanawake – Kiambu, Councillors, Catholic Dioceses, Justice and Peace, NGO’s, Chamber of Commerce, Mau Mau Veterans Society, KNUT, DP, Churches and individuals. Com. Lethome invited Prof. Ghai to give opening remarks on the Commission’s work and civic education. Prof. Ghai welcomed participants to the meeting and apologised for keeping them waiting as some of them had arrived as early as 8.00 a.m. -

Sediment Dynamics and Improvised Control Technologies in the Athi River Drainage Basin, Kenya

Sediment Dynamics in Changing Environments (Proceedings of a symposium held 485 in Christchurch, New Zealand, December 2008). IAHS Publ. 325, 2008. Sediment dynamics and improvised control technologies in the Athi River drainage basin, Kenya SHADRACK MULEI KITHIIA Postgraduate Programme in Hydrology, Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Nairobi, PO Box 30197, 00100 GPO, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] Abstract In Kenya, the changing of land-use systems from the more traditional systems of the 1960s to the present mechanized status, contributes enormous amounts of sediments due to water inundations. The Athi River drains areas that are subject to intense agricultural, industrial, commercial and population settlement activities. These activities contribute immensely to the processes of soil erosion and sediment transport, a phenomenon more pronounced in the middle and lower reaches of the river where the soils are much more fragile and the river tributaries are seasonal in nature. Total Suspended Sediments (TSS) equivalent to sediment fluxes of 13 457, 131 089 and 2 057 487 t year-1 were recorded in the headwater areas, middle and lower reaches of the river, respectively. These varying trends in sediment transport and amount are mainly due to the chemical composition of the soil coupled with the land-soil conservation measures already in practice, and which started in the 1930s and reached their peak in the early 1980s. This paper examines trends in soil erosion and sediment transport dynamics progressively downstream. The land-use activities and soil conservation, control and management technologies, which focus on minimizing the impacts of overland flow, are examined to assess the economic and environmental sustainability of these areas, communal societal benefits and the country in general. -

Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya

sustainability Article Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya Hang Ren 1,2 , Wei Guo 3 , Zhenke Zhang 1,2,*, Leonard Musyoka Kisovi 4 and Priyanko Das 1,2 1 Center of African Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210046, China; [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3 Department of Social Work and Social Policy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Geography, Kenyatta University, Nairobi 43844, Kenya; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-025-89686694 Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract: The widespread informal settlements in Nairobi have interested many researchers and urban policymakers. Reasonable planning of urban density is the key to sustainable development. By using the spatial population data of 2000, 2010, and 2020, this study aims to explore the changes in population density and spatial patterns of informal settlements in Nairobi. The result of spatial correlation analysis shows that the informal settlements are the centers of population growth and agglomeration and are mostly distributed in the belts of 4 and 8 km from Nairobi’s central business district (CBD). A series of population density models in Nairobi were examined; it showed that the correlation between population density and distance to CBD was positive within a 4 km area, while for areas outside 8 km, they were negatively related. The factors determining population density distribution are also discussed. We argue that where people choose to settle is a decision process between the expected benefits and the cost of living; the informal settlements around the 4-km belt in Nairobi has become the choice for most poor people. -

The Children and Youth Empowerment Centre (CYEC), Nyeri

The Children and Youth Empowerment Centre (CYEC), Nyeri. The Centre is located approximately 175 kilometers north of Nairobi on the outskirts of Nyeri town, the administrative headquarters of both Nyeri East District and Kenya’s Central Province. CYEC is an initiative of the national program for street dwelling persons and is intended to play a central role in the innovation of holistic and sustainable solutions for the population of street dwelling young people in Kenya. The Pennsylvania State University has been involved with the CYEC since 2009. Students from both the Berks and Main campuses of Penn State have focused on areas including bio-medical engineering, architectural engineering, teaching/literacy, and agriculture to help the CYEC. At the Center we have participated in constructing a green house, a drip irrigation center, creating books for the children, conducting various types of research, and much more. In 2010 the CYEC asked if Penn State would focus on the creation of an Eco-Village in Lamuria, a sustainable and eco-friendly village where the street children could go once they have reached adulthood to work and participate in a community environment and economy. Under the direction of Janelle Larson and Sjoerd Duiker, the 497C Agricultural Systems in East Africa class was The undeveloped Eco-Village site created at the Main campus. Our class consisted of only (2010) six students (five of whom were able to travel to Kenya) and met once every other Friday for two hours. This specific course focused on conducting research on agricultural production in semi-arid regions of east Africa, culminating with an opportunity for application through on-site assessment work in Kenya. -

Industrialization of Athi River Town

\l INDUSTRIALIZATION OF ATHI ( f RIVFR TOWN ' BY CALEB (m o * MIRERI This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requ i rements of the degree of Masters of Arts in Planning in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Architecture, Design and Development of the University of Nairobi. May 21st., 1992 DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. Cand idate---- 's“-— ^ ------ ignature ) Caleb Mc’Mireri DEPARTMENT OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING Faculty of Architecture. Design and Development P. 0. Bex 3 0 19 7 . Tel. 2 7 4 41 UNIVERSITY Of NAIROBI. This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor. S i g n e d -^*3^l __ Dr. George Ngugi (Supervisor) June 21st, 1992. ITT DEDICATION In Memorium of Jaduong’ James Mireri IV Acknowledgement A great many people helped me develop this thesis most of whom I cannot mention their names here. 1 am indebted to them all but in particular to my Supervisor Dr. George Ngugi of the University of Nairobi. His comments were consistently thoughtful and insightful and he persistently sought to encourage and support me. Also, Dr. Peter Ngau of the University of Nairobi gave me a far reaching support throughout the time of this thesis writing, by his incisive comments. T also want to thank all academic members of staff and students of D.U.R.P, who listened to the early versions of this study in seminars and the information they offered was of great help. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Kenya – Malindi Integrated Social Health Development Programme - Mishdp

Ufficio IX DGCS Valutazione KENYA – MALINDI INTEGRATED SOCIAL HEALTH DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME - MISHDP INSERIRE UNA FOTOGRAFIA RAPPRESENTATIVA DEL PROGETTO August 2012 Evaluation Evalutation of the “Kenya – Development integrated Programme” Initiative DRN Key data of the Project Project title Malindi–Ngomeni Integrated Development Programme Project number AID N. 2353 Estimated starting and May 2006 /April 2008 finishing dates Actual starting and May 2006 / December 2012 finishing dates Estimated Duration 24 months Actual duration 80 months due to the delays in the approval of the Programme Bilateral Agreement, allocation of funds, and delays in the activities implementation. Donor Italian Government DGCD unit administrator Technical representative in charge of the Programme: Dr Vincenzo Racalbuto Technical Area Integrated development Counterparts Coast Development Authority (CDA) Geographical area Kenya, Coastal area, Malindi and Magarin districts*, with particular attention to the Ngonemi area During the planning and the start of the project, Magarini district was part of the Malindi district, in the initial reports, in fact, Magarini is referred to as Magarini Division of the Malindi District. Since the mid 2011 the Magarini Division becomes a District on its own Financial estimates Art. 15 Law 49/87 € 2.607.461 Managed directly € 487.000 Expert fund € 300.000 Local fund € 187.000 TOTALE € 3.094.461 KEY DATA OF THE EVALUATION Type of evaluation Ongoing evaluation Starting and Finishing dates of the June-August 2012 evaluation mission Members of the Evaluation Team Marco Palmini (chief of the mission) Camilla Valmarana Rapporto finale Agosto 2012 Pagina ii Evalutation of the “Kenya – Development integrated Programme” Initiative DRN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Malindi Integrated Social Health Development Programme (MISHDP) has been funded by a grant of the DGCD, according to article 15 of the Regulation of the Law 49/87, for an amount of € 2.607.461, in addition to € 487.000 allocated to the direct management component. -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Marsabit County Disease Surveillance and Response

ACCESS TO TREATMENT FOR NEGLECTED DISEASES – Experiences In Marsabit County Presented by: Abduba Liban CDSC, Marsabit County 0n 9th February 2016 at the ASTMH Conference OUTLINE 1. Brief county profile 2. Status of kala-azar marsabit county 3. Diagnosis and Treatment of Kala azar in Marsabit 4. Challenges of Accessing Treatment 5. Addressing the challenges at County Level 6. Way forward Marsabit County County Profile County Population • Visceral leishmaniasis VL (Kala azar) . Kala azar a systemic parasitic disease . It is transmitted through infected female sand fly. There are three forms of leishmaniasis; Visceral leishmanaisis (VL), Cutaneous, Muco-cutaneous . There are three endemic foci in kenya o Northwest Kenya - West Pokot, Baringo and Turkana o Eastern Province - Machakos, Kitui, Mwingi and kyuso o North-eastern Province - along the Somali border Visceral Leishmaniasis in Marsabit . VL is the common form leishmania in Marsabit . VL is a new problem in Marsabit county . There is only one treatment centre for kala azar in Marsabit – Marsabit Hospital . Distance from the furthest endemic region to the centre is 500km Kala-azar Cases by Months Kala-azar Cases by Locations Diagnosis & Treatment of Kala-azar in Marsabit Diagnosis and treatment is based on the Kenyan VL guidelines Diagnosis . A patient should be suspected in a patient from, or visiting, an endemic area who presents with: o Fever > 2 weeks o Splenomegaly o Weight loss o Diagnosis through rapid test kits – rK39 Diagnosis & Treatment of Kala-azar in Marsabit Diagnosis and treatment is based on the Kenyan VL guidelines Treatment If patient is found positive after all differentials are ruled out, they are: . -

Devolution in Kenya: an Opportunity for Increased Public Participation, Reduced Corruption, and Improved Service Delivery

DEVOLUTION IN KENYA: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR INCREASED PUBLIC PARTICIPATION, REDUCED CORRUPTION, AND IMPROVED SERVICE DELIVERY by HAYLEY ELSZASZ Ngonidzashe Munemo, Advisor A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in Political Science WILLIAMS COLLEGE Williamstown, Massachusetts MAY 11, 2016 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter I: History of Local Government in Kenya………………………………..32 Independence and the Kenyatta Presidency The Moi Era Period of Democratization Constitutional Reforms Chapter II: Participation and Corruption in Post-Devolution Kenya……..……...61 Participation in Kenya’s Local Governments Disengagement Corruption Post-2010 Actions to Counter Corruption Perceptions of Corruption Chapter III: Healthcare Delivery in Post-Devolution Kenya……………………..94 Constitutional Framework Financing Local Healthcare Healthcare in Counties Healthcare System Post-Devolution Health Sector Explanations and Predictions Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….120 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………..137 ii Figures and Tables Figure 2.1 Voter Turnout 1992-2013 69 Table 0.1: Vote Margins in County Elections 24 Table 0.2: Party in Power: County Government 25 Table 0.3: Presidential Outcomes 2013 27 Table 0.4: Centrality of Counties 29 Table 1.1: The Provincial Administration: Kenyatta 36 Table 1.2: The Provincial Administration: Moi 46 Table 1.3: Devolved Local Government 57 Table 2.1: Voter Turnout 1992-2013 by Province 70 Table 2.2: Members of County Assemblies 77 Table 2.3: Qualities of the Most Corrupt Counties 83 Table 2.4: Bribes in Exchange for Services 91 Table 3.1: Tiers of Health Services 95 Table 3.2 Local Revenue & Central Government Grants 100 Table 3.3 Central Government Grants to the Counties 102 Table 3.4: Vaccination Rates by Province 113 Table 3.5: Births Delivered in a Health Facility by Province 114 Table 3.6: Infant Mortality by Province 115 Table 3.7: Antenatal Care by Province 116 Note on currency usage: All figures are given in Kenyan Shillings (KSh). -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

A PR I L 2 0 1 0 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Acknowledgements The report has been written by Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman, who take responsibility for its contents and conclusions. We wish to thank our co-researchers Halima Shuria, Hussein A. Mahmoud, and Amina Soud for their substantive contribution to the research process. Andrew Catley, Lynn Carter, and Jan Bachmann provided insightful comments on a draft of the report. Dawn Stallard’s editorial skills made the report more readable. For reasons of confidentiality, the names of some individuals interviewed during the course of the research have been withheld. We wish to acknowledge and thank all of those who gave their time to be interviewed for the study.