Medieval Resource Assessment for the Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selfbuild Register Extract

Address 4 When Ready Adults Children Individual Property Size Parishes Date Added Beds 1 - 2 years 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | East Cowes | Nettlestone and Seaview 22/02/2018 Dorset within 1 year 2 0 2 bedroom property Sandown | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/04/2016 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Nettlestone and Seaview | Ryde | St Helens 21/04/2016 Isle of Wight 3 - 5 years 0 0 3 bedroom property Freshwater | Gurnard | Totland 22/04/2016 within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Freshwater | Niton and Whitwell 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 2 bedroom property Ryde | Sandown | St Helens 21/04/2016 Leicestershire 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Bembridge | Freshwater | St Helens 20/03/2017 Leics within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Brighstone | Totland | Yarmouth 20/03/2017 1 - 2 years 5 0 4 bedroom property Cowes | Gurnard 15/08/2016 London within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Bembridge | Ryde | St Helens 07/08/2018 London within 1 year 2 0 4 bedroom property Ryde | Shanklin | Ventnor 13/03/2017 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Chale | Freshwater | Totland 08/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property East Cowes | Newport | Wroxall 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight 1 - 2 years 2 0 2 bedroom property Freshwater | Shalfleet | Yarmouth 10/02/2017 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Gurnard | Newport | Northwood 11/04/2016 Isle of Wight within 1 year 2 0 3 bedroom property Fishbourne | Havenstreet and Ashey | Wootton 22/04/2016 Isle Of Wight within 1 year 3 0 3 bedroom property -

Scheme of Polling Districts As of June 2019

Isle of Wight Council – Scheme of Polling Districts as of June 2019 Polling Polling District Polling Station District(s) Name A1 Arreton Arreton Community Centre, Main Road, Arreton A2 Newchurch All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch A3 Apse Heath All Saints Church Hall, High Street, Newchurch AA Ryde North West All Saints Church Hall, West Street, Ryde B1 Binstead Binstead Methodist Schoolroom, Chapel Road, Binstead B2 Fishbourne Royal Victoria Yacht Club, 91 Fishbourne Lane BB1 Ryde South #1 5th Ryde Scout Hall, St Johns Annexe, St Johns Road, Ryde BB2 Ryde South #2 Ryde Fire Station, Nicholson Road C1 Brading Brading Town Hall, The Bull Ring, High Street C2 St. Helens St Helens Community Centre, Guildford Road, St. Helens C3 Bembridge North Bembridge Village Hall, High Street, Bembridge C4 Bembridge South Bembridge Methodist Church Hall, Foreland Road, Bembridge CC1 Ryde West#1 The Sherbourne Centre, Sherbourne Avenue CC2 Ryde West#2 Ryde Heritage Centre, Ryde Cemetery, West Street D1 Carisbrooke Carisbrooke Church Hall, Carisbrooke High Street, Carisbrooke Carisbrooke and Gunville Methodist Schoolroom, Gunville Road, D2 Gunville Gunville DD1 Sandown North #1 The Annexe, St Johns Church, St. Johns Road Sandown North #2 - DD2 Yaverland Sailing & Boating Club, Yaverland Road, Sandown Yaverland E1 Brighstone Wilberforce Hall, North Street, Brighstone E2, E3 Brook & Mottistone Seely Hall, Brook E4 Shorwell Shorwell Parish Hall, Russell Road, Shorwell E5 Gatcombe Chillerton Village Hall, Chillerton, Newport E6 Rookley Rookley Village -

Planning & Infrastructure Services Schedule Of

PLANNING & INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES SCHEDULE OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND OTHER RELATED SUBMISSIONS DEALT WITH UNDER THE DELEGATE PROCEDURE DECISIONS TAKEN DURING THE WEEKS ENDING 05th March 2021 Acronym List GTD Granted REF Refused SPL Split Decision PAGTD Prior Approval Granted PAREF Prior Approval Refused Report of Planning and Infrastructure Services Applications Approved Decisions Made On: 01/03/2021 Application No: 20/02198/TW Location: 4 Lake Hill Lake Sandown Isle Of Wight PO36 9HA Proposal: T1; Sweet Chestnut - situated as detailed in the application is to have the crown lied to approximately 4 metres and crown cleaned. T2; Sweet Chestnut - situated as detailed in the application is to be felled to near ground level. Alternatively, could be left as a branchless hulk giving potential habitat for wildlife. Decision Date: 01/03/2021 Parish: Lake Ward: Lake North Case Officer: Jerry Willis Decision: GTD Application No: 20/02196/FUL Location: 3A Lake Industrial Way Lake Sandown Isle Of Wight PO36 9PL Proposal: Change of use from Class B1/B8 to Class B2 (motorcycle MOT testing, tuning and servicing) and/or Class B8 (storage and distribuon) Decision Date: 01/03/2021 Parish: Lake Ward: Lake South Case Officer: Maria Bishop Decision: GTD Application No: 20/02236/HOU Location: The Barn Bachelors Farm Canteen Road Newchurch Ventnor Isle Of Wight PO38 3AG Proposal: Installation of replacement enlarged window on south east elevation (revised scheme) Decision Date: 01/03/2021 Parish: Newchurch Ward: Arreton And Newchurch Case Officer: Julie Wilkins Decision: GTD Application No: 20/02199/TW Location: 14 Glendale Close Wootton Ryde Isle Of Wight PO33 4RF Proposal: T1; Oak situated as detailed in the application is to have two lowest branches removed. -

HEAP for Isle of Wight Rural Settlement

Isle of Wight Parks, Gardens & Other Designed Landscapes Historic Environment Action Plan Isle of Wight Gardens Trust: March 2015 2 Foreword The Isle of Wight landscape is recognised as a source of inspiration for the picturesque movement in tourism, art, literature and taste from the late 18th century but the particular significance of designed landscapes (parks and gardens) in this cultural movement is perhaps less widely appreciated. Evidence for ‘picturesque gardens’ still survives on the ground, particularly in the Undercliff. There is also evidence for many other types of designed landscapes including early gardens, landscape parks, 19th century town and suburban gardens and gardens of more recent date. In the 19th century the variety of the Island’s topography and the richness of its scenery, ranging from gentle cultivated landscapes to the picturesque and the sublime with views over both land and sea, resulted in the Isle of Wight being referred to as the ‘Garden of England’ or ‘Garden Isle’. Designed landscapes of all types have played a significant part in shaping the Island’s overall landscape character to the present day even where surviving design elements are fragmentary. Equally, it can be seen that various natural components of the Island’s landscape, in particular downland and coastal scenery, have been key influences on many of the designed landscapes which will be explored in this Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP). It is therefore fitting that the HEAP is being prepared by the Isle of Wight Gardens Trust as part of the East Wight Landscape Partnership’s Down to the Coast Project, particularly since well over half of all the designed landscapes recorded on the Gardens Trust database fall within or adjacent to the project area. -

The London Gazette, 9Th December 1976 16551

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 9TH DECEMBER 1976 16551 IPSWICH BOROUGH COUNCIL 3. B.3330 from the junction with Marlborough Road, Ryde ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1967 (SECTION 1) to the junction with Upper Green Road, St. Helens. The Borough of Ipswich (Constable Road) (One Way) 4. B.3395 from the junction with Yaverland Cross to the Order 1976 junction with B.3329 High Street (via Yaverland Road, Culver Parade) ; B.3329 High Street, Sandown from the Notice is hereby given that on the 6th December 1976 the junction with B.3395 Culver Parade to the junction with Ipswich Borough Council (hereinafter referred to as "the A.3055 Broadway (via Beachfield Road), and Avenue Road Council") pursuant to arrangements made under section from the junction with B.3329 High Street, San-down to the 101 of the Local Government Act 1972 with the Suffolk junction with A.3055 Broadway. County Council in exercise of the powers of the said County Council under section 1 of the Road Traffic Regula- 5. C.58 from the junction with Briddlesford Road to the tion Act 1967 as amended by Part IX of the Transport junction with A.3054 Quarr Hill (via Combley Road, Act 1968 and Schedule 19 to the Local Government Act Havenstreet Road, Newnham Road) ; C.59 from the junction 1972 (which said Act of 1967 as so amended is hereinafter with Pellhurst Road to the junction Rowlands Cross (via referred to as " the Act of 1967 ") and of all other enabling Upton Road, Stroudwood Road) and C.61 Carter Road from powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of the junction with Upton Cross to the junction with Ashey Police in accordance with section 84C (1) of the Act of Road. -

BULLETIN Feb 09

February 2009 Issue no.51 Bulletin Established 1919 www.iwnhas.org Contents Page(s) Page(s) President`s Address 1-2 Saxon Reburials at Shalfleet 10-11 Natural History Records 2 Invaders at Bonchurch 11 Country Notes 3-4 New Antiquarians 12-13 Brading Big Dig 4-5 General Meetings 13-22 Andy`s Notes 5-7 Section Meetings 22-34 Society Library 7 Membership Secretaries` Notes 34 Delian`s Archaeological Epistle 7-9 White Form of Garden Snail 9-10 President`s Address On Friday 10 th October 2008 a large and varied gathering met at Northwood House for a very special reason. We were attending the launch of HEAP, an unfortunate acronym, which still makes me think of garden rubbish. However, when the letters are opened up we find The Isle of Wight Historic Environ- ment Action Plan, a title which encompasses the historic landscape of the Island, the environment in which we live today and the future which we are bound to protect. It extends the work already being un- dertaken by the Island Biodiversity Action Plan, a little known but invaluable structure, which has al- ready been at work for ten years. This body brings together the diverse groups, national and local, whose concern is with the habitats and species which are part of our living landscape. The HEAP will do much the same at a local level for the landscape of the Island, the villages, towns, standing monuments which take us from the Stone Age to the present day and, most importantly, the agricultural landscape which is particularly vulnerable to intrusion and sometimes alarming change. -

Tithe Catalogue

Tithe Catalogue General JER/T/001 1837 Records of Parochial Meetings re. Commutation of Tithes. Parishes of Brading, Brighstone, Calbourne, Freshwater, Godshill, Mottistone, Niton, Northwood, St Lawrence, Shorwell, Whippingham, Whitwell and Yaverland only. JER/T/002 1837-1845 Minute Book of Parochial Meetings re. Commutation of Tithes. Whole Island except Brook and Kingston. JER/T/003 1837-1838 Day Book of Expenses of Messrs Sewells as Attorney for Tithe Commissioners. JER/T/004 1837 Deeds of Attorney Thomas, Henry and Robert Burleigh Sewell appointed to act for various land owners in Parochial Tithe Commutation Agreements. JER/T/005 1837 Bundle of loose Deeds of Attorney, as above. JER/T/006 ND c.1837 Book of Tithe Commutation Averages. Gives details of tithe owners, poor rates, highway rates, previous compositions. Parishes of Brighstone, Calbourne, Freshwater, Mottistone, Niton and Yaverland only. JER/T/007 1838-1849 Letter Book of Sewells as Attorneys to the Tithe Commisioners. JER/T/008 ND c.1846 All island index to landowners with parishes and field numbers from tithe schedules. Arreton JER/T/009 ND c.1837 Poor Rate, Highway Rate and Land Tax Assessments, parish of Arreton. JER/T/010 1837 Notices and letters re. calling of Parochial Meeting, parish of Arreton. JER/T/011 ND c.1838 Bundle of papers re. tithe free lands, parish of Arreton. JER/T/012 1815-1835 Vicarial Tithe Assessments, parish of Arreton. JER/T/013 1829-1835 Bundle of papers re Assessment of Rectorial Tithes, parish of Arreton. JER/T/014 ND c.1838 Schedules of land belonging to various farms in the parish of Arreton, includes some not subject to tithes. -

Feed Premises

Isle of Wight Council Trading Standards Service Premise Registration No. Categories Chale Farm, Church Place, Chale, Isle Of Wight, PO38 2HB GB867‐1649 R13 4 High Road, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 5PD GB867‐4569 R13 17 Melbourne Street, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 1QY GB867‐8054 R13 17 Lugley Street, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 5HD GB867‐10022 R13 105 Horsebridge Hill, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 5TL GB867‐11781 R13 Highwood House, Highwood Lane, Rookley, Isle Of Wight, PO38 3NN GB867‐17218 R13 Upper Shide Mill House, Blackwater Road, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 3BB GB867‐17311 R13 Marvel Farm, Marvel Lane, Newport, Isle Of Wight, PO30 3DT GB867‐17314 R13 50 Hefford Road, East Cowes, Isle Of Wight, PO32 6QU GB867‐22053 R13 Stockbridge Cottage, Slay Lane, Whitwell, Isle Of Wight, PO38 2QF GB867‐23244 R13 Merstone Cottage, Merstone Lane, Arreton, Isle Of Wight, PO30 3DE GB867‐25574 R13 Cherry Acre Cottage, Rew Lane, Wroxall, Isle Of Wight, PO38 3AX GB867‐26880 R13 1 Lessland Cottages, Lessland Lane, Godshill, Isle Of Wight, PO38 3AS GB867‐27303 R13 Rock Point, Lower Woodside Road, Wootton, Isle Of Wight, PO33 4JT GB867‐28752 R13 Sweet Briar Cottage, East Ashey Lane, Ryde, Isle Of Wight, PO33 4AT GB867‐42499 R13 17 St Michaels Avenue, Ryde, Isle Of Wight, PO33 3DY GB867‐43939 R13 Church Cottage, Main Road, Thorley, Isle Of Wight, PO41 0SS GB86745887 R13 Mattingley Farm, Main Road, Wellow, Isle Of Wight, PO41 0SZ GB867‐48423 R13 Shalcombe Manor, Brook Road, Calbourne, Isle Of Wight, PO41 0UF GB867‐49656 R13 Reeah Ii, Hamstead Road, Cranmore, -

6 Brighstone, Chale & Niton Itineraries

BE A BRIGHSTONE, CHALE & NITON Experience sustainable transport 6 ITINERARIES It’s easy to explore the Isle of Wight using sustainable transport. Here are a few ideas for fun local days out – no car required! Everything’s better by bus. It’s more fun than a car, the kids don’t fi ght and BETTER BY BUS you get brilliant views. From Brighstone you can jump on the Southern Vectis route 12 bus and you’ll be in Freshwater in 20 minutes… so long as you don’t get stuck behind a tractor, which happens rather a lot around 1here! In Freshwater, go for a bracing walk up Tennyson Down, right up to the monument at the top. You’ll be rewarded by views over the iconic Needles. Head back the way you came, then get the route 7 bus to Yarmouth to check out the posh boutiques and restaurants. Or snap up a 24hr hop-on, hop-off bus ticket and explore the spectacular South on an Island Coaster. Stop offs include Isle of Wight Pearl where you can splurge on jewellery and a cream tea, and then go on to subtropical Ventnor with its Botanic Garden, and Shanklin old village. The Island Coaster bus will take you all the way to the golden sands of Ryde where you can pop into the Bus and Coach Museum (it’s free!). You’re never far from dinosaurs here. The Isle of Wight is known as DINO HUNT Dinosaur Island, as it’s the fossil capital of Europe. Rare species and whole skeletons have been found along the coast, sometimes by holidaymakers just messing about on the beach. -

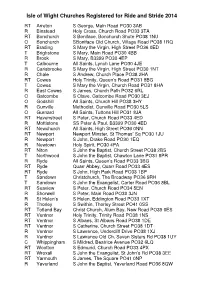

Isle of Wight Churches Registered for Ride and Stride 2014

Isle of Wight Churches Registered for Ride and Stride 2014 RT Arreton S George, Main Road PO30 3AB R Binstead Holy Cross, Church Road PO33 3TA RT Bonchurch S Boniface, Bonchurch Shute PO38 1NU O Bonchurch SBoniface Old Church, Village Road PO38 1RQ RT Brading S Mary the Virgin, High Street PO36 0ED T Brighstone S Mary, Main Road PO30 4BB R Brook S Mary, B3399 PO30 4EP T Calbourne All Saints, Lynch Lane PO30 4JE R Carisbrooke S Mary the Virgin, High Street PO30 1NT R Chale S Andrew, Church Place PO38 2HA RT Cowes Holy Trinity, Queen’s Road PO31 8BG T Cowes S Mary the Virgin, Church Road PO31 8HA R East Cowes S James, Church Path PO32 6RL O Gatcombe S Olave, Gatcombe Road PO30 3EJ O Godshill All Saints, Church Hill PO38 3HY R Gunville Methodist, Gunville Road PO30 5LS O Gurnard All Saints, Tuttons Hill PO31 8JA RT Havenstreet S Peter, Church Road PO33 4ED R Mottistone SS Peter & Paul, B3399 PO30 4ED RT Newchurch All Saints, High Street PO36 0NN RT Newport Newport Minster, St Thomas’ Sq PO30 1JU R Newport S John, Drake Road PO30 1EQ R Newtown Holy Spirit, PO30 4PA RT Niton S John the Baptist, Church Street PO38 2BS T Northwood S John the Baptist, Chawton Lane PO31 8PR R Ryde All Saints, Queen’s Road PO33 3BG RT Ryde Quarr Abbey, Quarr Road PO33 4ES RT Ryde S John, High Park Road PO33 1BP T Sandown Christchurch, The Broadway PO36 9RH T Sandown S John the Evangelist, Carter Road PO36 8BL RT Seaview S Peter, Church Road PO34 5EN R Shorwell S Peter, Main Road PO30 3JN R St Helen’s S Helen, Eddington Road PO33 1XT R Thorley S Swithin, Thorley -

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online www.iow.gov.uk/planning using the link labelled ‘Search planning applications made since February 2004’. Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at www.iow.gov.uk/planning. For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS WHICH FALL WITHIN MORE THAN ONE PARISH OR WARD WILL APPEAR ONLY ONCE IN THE LIST UNDER THE PRIMARY PARISH PRESS LIST DATE: 8th January 2021 Application No: 20/00513/FUL -

Lease of Premises to William Aylward 1851. HG / 2 / 297B Handwritten Note

Lease of premises to William Aylward 1851. HG / 2 / 297b Handwritten note, " Whitecliff – Brading". This Indenture made the twentieth day of December in the Year of our Lord one thousand, eight hundred and fifty one Between Sir Graham Eden Hamond of Norton Lodge in the parish of Freshwater in the Isle of Wight, Baronet, of the one part and William Aylward of the parish of cattle Wymmering in the County of Southampton, Brickmaker, of the other part, Witnesseth that in consideration of the Rent and Covenants hereinafter reserved and contained, the said Sir Graham Eden Hamond doth hereby demise and lease unto the said William Aylward, his Executors, administrators and assigns All that piece or parcel of Land situate at Whitecliff in the parish of Brading in the said Isle adjoining the seashore as the same is more particularly described by the Plan thereof drawn in the Margin of these presents on part of which said piece of Land there was formerly a Brick Kiln in the occupation of Cooper Together with full liberty to erect Kilns, Sheds and other Erections upon the said piece of land and to dig and get upon the said piece of land Brick-Earth, Loam, Sand, Chalk and Flints and to make and manufacture the same upon the said premises and not elsewhere into Bricks, Tiles and other articles for the purposes of Sale and to sell and dispose of the same when so manufactured, but not otherwise, Together also with all ways, paths, waters, profits, privileges and appurtenances to the said piece of land belonging .......