The Unanticipated Consequences of Deliberate Communication In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating the Landscape of Conflict: Applications of Dynamical Systems Theory to Addressing Protracted Conflict

Dynamics of Intractable Conflict Peter T. Coleman, PhD Robin Vallacher, PhD Andrzej Nowak, PhD International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution Teachers College, Columbia University New York, NY, USA Why are some intergroup conflicts impossible to solve and what can we do to address them? “…one of the things that frustrates me about this conflict, thinking about this conflict, is that people don’t realize the complexity… how many stakeholders there are in there…I think there is a whole element to this particular conflict to where you start the story, to where you begin the narrative, and clearly it’s whose perspective you tell it from…One of the things that’s always struck me is that there are very compelling narratives to this conflict and all are true, in as much as anything is true… I think the complexity is on so many levels…It’s a complexity of geographic realities…the complexities are in the relationships…it has many different ethnic pockets… and I think it’s fighting against a place, where particularly in the United States, in American culture, we want to simplify, we want easy answers…We want to synthesize it down to something that people can wrap themselves around and take a side on…And maybe sometimes I feel overwhelmed…” (Anonymous Palestinian, 2002) Four Basic Themes An increasing degree of complexity and interdependence of elements. An underlying proclivity for change, development, and evolution within people and social-physical systems. Extraordinary cognitive, emotional, and behavioral demands…anxiety, hopelessness. Oversimplification of problems. Intractable Conflicts: The 5% Problem Three inter-related dimensions (Kriesberg, 2005): Enduring Destructive Resistant Uncommon but significant (5%; Diehl & Goertz, 2000) 5% of 11,000 interstate rivalries between 1816-1992. -

Introductory Course on Dynamical Systems Theory and Intractable Conflict DST Course Objectives

Introductory Course on Dynamical Systems Theory and Intractable Conflict Peter T. Coleman Columbia University December 2012 This self-guided 4-part course will introduce the relevance of dynamical systems theory for understanding, investigating, and resolving protracted social conflict at different levels of social reality (interpersonal, inter-group, international). It views conflicts as dynamic processes whose evolution reflects a complex interplay of factors operating at different levels and timescales. The goal for the course is to help develop a basic understanding of the dynamics underlying the development and transformation of intractable conflict. DST Course Objectives Participants in this class will: Learn the basic ideas and methods associated with dynamical systems. Learn the relevance of dynamical systems for personal and interpersonal processes. Learn the implications of dynamical models for understanding and investigating conflict of different types and at different levels of social reality. Learn to think about conflict in a manner that allows for new and testable means of conflict resolution. Foundational Texts Nowak, A. & Vallacher, R. R. (1998). Dynamical social psychology. New York: Guilford Publications. Vallacher, R., Nowak, A., Coleman, P. C., Bui-Wrzosinska, L., Leibovitch, L., Kugler, K. & Bartoli, A. (Forthcoming in 2013). Attracted to Conflict: The Emergence, Maintenance and Transformation of Malignant Social Relations. Springer. Coleman (2011). The Five Percent: Finding Solutions to Seemingly Impossible Conflicts. Perseus Books. Coleman, P. T. & Vallacher, R. R. (Eds.) (2010). Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, Vol. 16, No. 2, 2010. (Special issue devoted to dynamical models of intractable conflict). Ricigliano, R. (2012).Making Peace Last. Paradigm. Burns, D. (2007). Systemic Action Research: A Strategy for Whole System Change. -

Towards a Theory of Sustainable Prevention of Chagas Disease: an Ethnographic

Towards a Theory of Sustainable Prevention of Chagas Disease: An Ethnographic Grounded Theory Study A dissertation presented to the faculty of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Claudia Nieto-Sanchez December 2017 © 2017 Claudia Nieto-Sanchez. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Towards a Theory of Sustainable Prevention of Chagas Disease: An Ethnographic Grounded Theory Study by CLAUDIA NIETO-SANCHEZ has been approved for the School of Communication Studies, the Scripps College of Communication, and the Graduate College by Benjamin Bates Professor of Communication Studies Mario J. Grijalva Professor of Biomedical Sciences Joseph Shields Dean, Graduate College 3 Abstract NIETO-SANCHEZ, CLAUDIA, Ph.D., December 2017, Individual Interdisciplinary Program, Health Communication and Public Health Towards a Theory of Sustainable Prevention of Chagas Disease: An Ethnographic Grounded Theory Study Directors of Dissertation: Benjamin Bates and Mario J. Grijalva Chagas disease (CD) is caused by a protozoan parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi found in the hindgut of triatomine bugs. The most common route of human transmission of CD occurs in poorly constructed homes where triatomines can remain hidden in cracks and crevices during the day and become active at night to search for blood sources. As a neglected tropical disease (NTD), it has been demonstrated that sustainable control of Chagas disease requires attention to structural conditions of life of populations exposed to the vector. This research aimed to explore the conditions under which health promotion interventions based on systemic approaches to disease prevention can lead to sustainable control of Chagas disease in southern Ecuador. -

A Look Into the Nature of Complex Systems and Beyond “Stonehenge” Economics: Coping with Complexity Or Ignoring It in Applied Economics?

AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS Agricultural Economics 37 (2007) 219–235 A look into the nature of complex systems and beyond “Stonehenge” economics: coping with complexity or ignoring it in applied economics? Chris Noell∗ Department of Agricultural Economics, University of Kiel, Germany Received 27 October 2006; received in revised form 23 July 2007; accepted 27 July 2007 Abstract Real-world economic systems are complex in general but can be approximated by the “open systems” approach. Economic systems are very likely to possess the basic and advanced emergent properties (e.g., self-organized criticality, fractals, attractors) of general complex systems.The theory of “self-organized criticality” is proposed as a major source of dynamic equilibria and complexity in economic systems. This is exemplified in an analysis for self-organized criticality of Danish agricultural subsectors, indicated by power law distributions of the monetary production value for the time period from 1963 to 1999. Major conclusions from the empirical part are: (1) The sectors under investigation are obviously self-organizing and thus very likely to show a range of complex properties. (2) The characteristics of the power law distributions that were measured might contain further information about the state or graduation of self-organization in the sector. Varying empirical results for different agricultural sectors turned out to be consistent with the theory of self-organized criticality. (3) Fully self-organizing sectors might be economically the most efficient. Finally, -

Music at the Edge of Chaos: a Complex Systems Perspective on File Sharing

Music at the Edge of Chaos: A Complex Systems Perspective on File Sharing Deborah Tussey∗ I. INTRODUCTION The twin developments of digital copying and global networking technologies have drastically transformed the information environment and have produced particularly acute dislocations in the music recording industry. The perceived threat to the industry posed by peer-to-peer (“P2P”) file sharing has inspired numerous proposals for legislative action, many involving major adjustments to or even abandonment of the copyright regime. Contemporary file sharing arose in the context of a system designed to produce and distribute musical recordings. This article approaches the issue of file sharing regulation1 by applying complexity theory and related principles of systems analysis to that system. Systems both occur naturally and result from human design.2 Complexity theory provides a conceptual model for a particular category of systems—complex adaptive systems3—and their evolution ∗ Associate Professor, Oklahoma City University School of Law. Thanks to Sam Lupica and to participants in the 2004 Works-in-Progress IP Colloquium at Boston University and the 2005 IP & Communications Law and Policy Scholars Roundtable at Michigan State University—DCL College of Law, for their comments on earlier versions of this article. The writing of this article was supported by a grant from the Kerr Foundation and Law Alumni Fund. 1. This article focuses on federal regulation through the U.S. copyright regime. International regulation falls outside the scope of the article except insofar as U.S. regulation will inevitably have transborder effects. 2. “[F]or reasons not yet explained, phenomena order themselves largely as discrete systems.” Lynn M. -

The Talking Cure Cody CH 2014

Complexity, Chaos Theory and How Organizations Learn Michael Cody Excerpted from Chapter 3, (2014). Dialogic regulation: The talking cure for corporations (Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Law. University of British Columbia). Available at: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0077782 Most people define learning too narrowly as mere “problem-solving”, so they focus on identifying and correcting errors in the external environment. Solving problems is important. But if learning is to persist, managers and employees must also look inward. They need to reflect critically on their own behaviour, identify the ways they often inadvertently contribute to the organisation’s problems, and then change how they act. Chris Argyris, Organizational Psychologist Changing corporate behaviour is extremely meet expectations120; difficult. Most corporate organizational change • 15% of IT projects are successful121; programs fail: planning sessions never make it into • 50% of firms that downsize experience a action; projects never quite seem to close; new decrease in productivity instead of an rules, processes, or procedures are drafted but increase122; and people do not seem to follow them; or changes are • Less than 10% of corporate training affects initially adopted but over time everything drifts long-term managerial behaviour.123 back to the way that it was. Everyone who has been One organization development OD textbook involved in managing or delivering a corporate acknowledges that, “organization change change process knows these scenarios -

The Thorny Path Toward Greening: Unintended Consequences, Trade- Offs, and Constraints in Green and Blue Infrastructure Planning, Implementation, and Management

Copyright © 2021 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Kronenberg, J., E. Andersson, D. N. Barton, S. T. Borgström, J. Langemeyer, T. Björklund, D. Haase, C. Kennedy, K. Koprowska, E. Łaszkiewicz, T. McPhearson, E. E. Stange, and M. Wolff. 2021. The thorny path toward greening: unintended consequences, trade- offs, and constraints in green and blue infrastructure planning, implementation, and management. Ecology and Society 26(2):36. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12445-260236 Research, part of a Special Feature on Holistic Solutions Based on Nature: Unlocking the Potential of Green and Blue Infrastructure The thorny path toward greening: unintended consequences, trade-offs, and constraints in green and blue infrastructure planning, implementation, and management Jakub Kronenberg 1, Erik Andersson 2,3, David N. Barton 4, Sara T. Borgström 5, Johannes Langemeyer 6,7, Tove Björklund 5, Dagmar Haase 7,8, Christopher Kennedy 9, Karolina Koprowska 1, Edyta Łaszkiewicz 1, Timon McPhearson 2,9,10, Erik E. Stange 11 and Manuel Wolff 7,8 ABSTRACT. Urban green and blue space interventions may bring about unintended consequences, involving trade-offs between the different land uses, and indeed, between the needs of different urban inhabitants, land users, and owners. Such trade-offs include choices between green/blue and non-green/blue projects, between broader land sparing vs. land sharing patterns, between satisfying the needs of the different inhabitants, but also between different ways of arranging the green and blue spaces. We analyze investment and planning initiatives in six case-study cities related to green and blue infrastructure (GBI) through the lens of a predefined set of questions—an analytical framework based on the assumption that the flows of benefits from GBI to urban inhabitants and other stakeholders are mediated by three filters: infrastructures, institutions, and perceptions. -

Thriving at the Edge of Chaos Vol

PM World Journal (ISSN: 2330-4480) Thriving at the Edge of Chaos Vol. IX, Issue VI – June 2020 Author: Jonathan Sapir www.pmworldjournal.com Book Review Reviewer: Shauna Skolnick PM WORLD BOOK REVIEW Book Title: Thriving at the Edge of Chaos; Managing Projects as Complex Adaptive Systems Author: Jonathan Sapir Publisher: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group List Price: $150.00 Format: Hardcover, 238 pages Publication Date: December 2019 ISBN: 9780367405403 Reviewer: Shauna Skolnick Review Date: May 2020 Introduction “Thriving at the Edge of Chaos” presents a compelling argument for embracing uncertainty rather than avoiding it. Sapir offers a framework for a total paradigm shift in methodology that would allow businesses to thrive in today’s modern, complex, rapidly changing world. This new mindset rejects the ineffective, rigid, yesteryear concepts of project management based around detailed planning and prediction, and replaces them with a more flexible Complex Adaptive System (CAS) methodology. Managing projects in a fluid system built to react favorably to change and chaos leads to skillfully riding the wave of unpredictability, and ultimately accelerating success and facilitating innovation. This book boldly challenges the stagnant standard operating procedures and principles of project management and forces us to consider whether they are too archaic to be effective anymore. In short, we cannot do today’s job with yesterday’s tools. It’s time for an upgrade; it’s time to retool. As our world evolves into a more advanced, complex, dare we say chaotic environment, the methodologies with which we work must also evolve so that we can successfully thrive at the edge of chaos. -

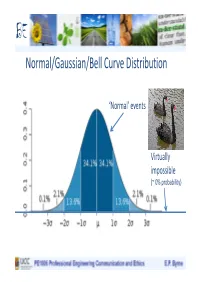

Normal/Gaussian/Bell Curve Distribution

BE Normal/Gaussian/Bell Curve Distribution ‘Normal’ events Virtually impossible (~ 0% probability) BE Models of Distribution Normal/ Gaussian/ Bell curve Power law/fat- distribution tailed/scalar/fractal distributions BE Normal versus Power law/Fractal Distributions Highly surprising: as impossible according to this model Normal (Catastrophic) unexpected Distribution (blue) ‘black swan’ events Desirable behaviour, - to be avoided and/or accompanied by robustness, consequences reduced, redundancy, loose coupling associated with highly efficient, Scalar/Fractal optimised tightly coupled distribution (red) complex systems Limits distant/ unknown BE Power law/Fractal/Scalar/Fat-tailed Distributions Complex Systems: e.g. Ecological, Social, Economic, Technological systems (with human input), Sustainability, Food Production, Water, Energy Generation and Distribution, etc., etc.. Highly optimised, Tight coupling Vulnerable to Limits ‘unexpected’ unknown unpredictable Catastrophic Events BE Power law/Fractal/Scalar/Fat-tailed Distributions Complex Systems: e.g. Ecological, Social, Economic, Technological systems (with human input), Sustainability, Food Production, Water, Energy Generation and Distribution, etc., etc.. Highly optimised, Tight coupling Reduce coupling, increase redundancy Vulnerable to => reduced Limits ‘unexpected’ unknown ‘unsustainability’ unpredictable Catastrophic Events BE Power law/Fractal/Scalar/Fat-tailed Distributions Normal/ Gaussian/ Fat-tailed/ Bell curve Power law/fractal distribution distribution BE Power law/Fractal/Scalar/Fat-tailed Distributions 160 2.5 151 countries <10m 140 2 (65% of 234) 5% of global pop 1.5 120 1. Choose 50 countries randomly with populations (median: 5m) 1 100 2. Estimate distribution on0.5 basis of known data (normal?!) 80 3. Choose 10 people randomly0 0.8 1.3 1.8 2.3 60 of Countries) (No.Log 4. Four are from: China, India Log(2 each). -

Ambiguity Neglect and Policy Ineffectiveness

Unintended Consequences: Ambiguity Neglect and Policy Ineffectiveness Lorán Chollete and Sharon Harrison* November 27, 2019 Abstract When a policymaker introduces a novel policy, she will not know what the citizens’ choices will be under the policy. In the face of novel policies, citizens themselves may have to construct new choice sets. Such choice construction imparts inherent ambigu- ity to novel policy implementation: the policymaker does not know the probability that citizens will select actions that accord with the intent of her policy. A policymaker who assumes that citizens will follow a fixed approach may therefore be susceptible to am- biguity neglect, which can result in her policies having unintended consequences. We provide examples of unintended consequences as well as a simple formalization. Our results suggest that before implementing novel policies, governments and policymakers should attempt to elicit preferences from the citizens who will be affected. Keywords: Ambiguity Neglect; Choice Construction; Indeterminacy; Policy Ineffectiveness; Unintended Consequences *Chollete is at the Welch College of Business at Sacred Heart University, email chol- [email protected], and Harrison is at Barnard College, email [email protected]. We acknowl- edge support from Barnard College, Sharon Harrison, PI. 1 Introduction And it came to pass...that he said, Escape for thy life; look not behind thee... lest thou be consumed... But his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt. Genesis 19: 17-26. Individuals do not always follow orders, even when the consequences may be highly detri- mental to them. We may fail to adhere to the choices that a policy intended to elicit because of resource constraints, stubbornness, behavioral considerations, bounded rationality, and other factors that lead us to depart from obedience. -

Unintended Consequences - Wikipedia, the Free

Unintended consequences - Wikipedia, the free... http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unintended_cons... 11/02/2014 09:00 Unintended consequences From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences ) are outcomes that are not the ones intended by a purposeful action. The term was popularised in the 20th century by American sociologist Robert K. Merton.[1] Unintended consequences can be roughly grouped into three types: A positive, unexpected benefit (usually referred to as luck, serendipity or a windfall). A negative, unexpected detriment occurring in addition to the An erosion gully in Australia caused desired effect of the policy (e.g., while irrigation schemes by rabbits. The release of rabbits in provide people with water for agriculture, they can increase Australia for hunting purposes has had waterborne diseases that have devastating health effects, such serious unintended ecological as schistosomiasis). consequences. A perverse effect contrary to what was originally intended (when an intended solution makes a problem worse) Contents 1 History 2 Causes 3 Examples 3.1 Unexpected benefits 3.2 Unexpected drawbacks 3.3 Perverse results 4 Unintended consequences of environmental intervention 5 See also 6 Notes 7 References History The idea of unintended consequences dates back at least to Adam Smith, the Scottish Enlightenment, and consequentialism (judging by results). [2] However, it was the sociologist Robert K. Merton who popularized this concept in the twentieth century. [1][3][4][5] In his 1936 paper, "The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action", Merton tried to apply a systematic analysis to the problem of unintended consequences of deliberate acts intended to cause social change. -

'Butterfly Politics

'Butterfly Politics CATHARINE A. MACKINNON The 'Belknap Pressof Harvard ('Universit y Press CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, ENGLAND 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Catharine A. Mac Kinnon All rights reserved Printed in the United Sratcs of America for the last woman I talked with and the next baby girl born First prmt[ng Interior design by Dean Bornstein Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: MacKinnon, Catharine A., author. Title: Butterfly politics!Catharinc A. MacKinnon. Description: Camhridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ;?.017. "EncompassingI legal and political interventions from 1976 to 2016, this volume collects moments of attempts to change the inequality of women to men and reflections on those attempts" Jncroduction. I Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2.016040443 I ISBN 9780674416604 (clothl Subjects: LCS!-1: Sex discrimination against women-Law and legislation-United States-History. I Sexual harassmcnt-L1.w and legislation-United States-History. I Rape-Law and leg[slation United States-History. I Pornography-Law and legislation- United States-History. I Women's rights-Umted States-History. I Feminist jurisprudence-United States. Classification: LCC KF4758 .M3;?.7 ;?.017 I DOC 34;?..7308/78-dc;?.3 LC record available at https:l/kcn.loc.gov'2016040443 CONTENTS Butterfly Politics I I. Change I. To Change the World for Women ( 1980) 1 I 2.. A Radical Act of Hope (1989) 23 3· Law's Power (1990) 28 4· To Quash a Lie (1991) 34 5. The Measure of What Matters (1992) 42 6. Intervening for Sex Equality ( 20 r 3) 47 II.Law Introduction, Symposium on Sexual Harassment (1981) 7.