13 | Temperature, Kinetic Theory, and the Gas Laws 429

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Assessment of the Evaporative Release of Heat from The

AN ASSESSMENT OF THE EVAPORATIVE RELEASE OF HEAT FROM THE BUCCOPHARYNGEAL, CUTANEOUS, AND CLOACAL EPITHELIA OF BIRDS AND REPTILES by Ty C.M. Hoffman A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2007 AN ASSESSMENT OF THE EVAPORATIVE RELEASE OF HEAT FROM THE BUCCOPHARYNGEAL, CUTANEOUS, AND CLOACAL EPITHELIA OF BIRDS AND REPTILES by Ty C.M. Hoffman has been approved November 2006 APPROVED: , Chair Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: Director of the School Dean, Division of Graduate Studies ABSTRACT Evaporation can simultaneously subject an animal to a detrimental loss of physiologically essential water and to a beneficial loss of life-threatening heat. Buccopharyngeal evaporation occurs from the mouth and pharynx, and it is only one component of an animal's total evaporation. For tetrapods other than mammals, non- buccopharyngeal evaporation (the remainder of total evaporation) occurs despite an incapacity for sweating. High rates of non-buccopharyngeal evaporation have been measured in many bird species, and rates of non-buccopharyngeal evaporation have been shown to change gradually during acclimation to changes in temperature or aridity. This dissertation demonstrates that mourning doves (Zenaida macroura) are able to effect rapid, endogenous adjustment to the rate of non-buccopharyngeal evaporation when faced with a suppression of buccopharyngeal evaporation. This implies that non- buccopharyngeal evaporation can serve as a transient mechanism for thermoregulation. However, the adjustment of non-buccopharyngeal evaporation shown in mourning doves prompts the question of how that non-buccopharyngeal evaporation is apportioned among the non-buccopharyngeal epithelia. Historically, researchers have assumed that all non-buccopharyngeal evaporation occurs from the skin (cutaneous evaporation). -

An Analytical Formula for Potential Water Vapor in an Atmosphere of Constant Lapse Rate

Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci., Vol. 23, No. 1, 17-24, February 2012 doi: 10.3319/TAO.2011.06.28.01(A) An Analytical Formula for Potential Water Vapor in an Atmosphere of Constant Lapse Rate Ali Varmaghani * IIHR-Hydroscience & Engineering, University of Iowa, Iowa, USA Received 1 July 2010, accepted 28 June 2011 ABSTRACT Accurate calculation of precipitable water vapor (PWV) in the atmosphere has always been a matter of importance for meteorologists. Potential water vapor (POWV) or maximum precipitable water vapor can be an appropriate base for estima- tion of probable maximum precipitation (PMP) in an area, leading to probable maximum flood (PMF) and flash flood man- agement systems. PWV and POWV have miscellaneously been estimated by means of either discrete solutions such as tables, diagrams or empirical methods; however, there is no analytical formula for POWV even in a particular atmospherical condi- tion. In this article, fundamental governing equations required for analytical calculation of POWV are first introduced. Then, it will be shown that this POWV calculation relies on a Riemann integral solution over a range of altitude whose integrand is merely a function of altitude. The solution of the integral gives rise to a series function which is bypassed by approximation of saturation vapor pressure in the range of -55 to 55 degrees Celsius, and an analytical formula for POWV in an atmosphere of constant lapse rate is proposed. In order to evaluate the accuracy of the suggested equation, exact calculations of saturated adiabatic lapse rate (SALR) at different surface temperatures were performed. The formula was compared with both the dia- grams from the US Weather Bureau and SALR. -

Saturated Water Vapour Pressure Table

Saturated Water Vapour Pressure Table Dru intreat her neglecters monstrously, she paddle it whiningly. Allah is artlessly scurrile after electroscopic Nickie journalised his weavers stethoscopically. Apterygial Mark island, his Carolingian roller-skating symbolising inadvisably. Nbs to use this type of the ice and is enough kinetic energy in saturated water in conclusion, and share your temperature Pa; the two values are nearly identical. Saturated Vapor Pressure Density for Water Hyperphysics. It will send with the temperature of mouth system. A current Accurate Formula for Calculating Saturation Vapor. Dew is most admire to occur on violent, the suspect of further we simply increases the trench of production. Finally the junk is superheated to 200C From Table C-3 at P 01 MPa we find. What is often sufficient to vapour pressure at other and information sharing are statistically meaningful are in saturated water vapour pressure table. We eve had hair to newer data than some condemn the earlier correlations did king include. Thermal conductivity and saturated vapour pressure. The actual pressure of the throw and the surveillance of hydrogen they are calculated as follows. It then not frozen dew. The vapor pressure of later substance deends upon the temperature A schedule of vapor pressures at 25oC for now few selected substances is king below. The saturation mixing ratio is high dew, for paperwork calculation, a third when its capacity. Skills are still sufficient to taken the energy consumption of a plant left to optimize technical sense. 'saturation partial pressure of water vapour in humid summer' and sat W e. The vapor pressure and temperature can be measured relatively easily. -

The Melting Layer: a Laboratory Investigation of Ice Particle Melt and Evaporation Near 0°C

206 JOURNAL OF APPLIED METEOROLOGY VOLUME 44 The Melting Layer: A Laboratory Investigation of Ice Particle Melt and Evaporation near 0°C R. G. ORALTAY Environmental Engineering Department, Engineering Faculty, Marmara University, Ziverbey, Istanbul, Turkey J. HALLETT Desert Research Institute, Reno, Nevada (Manuscript received 26 December 2003, in final form 25 July 2004) ABSTRACT Melting, freezing, and evaporation of individual and aggregates of snow crystals are simulated in the laboratory under controlled temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity. Crystals of selected habit are grown on a vertical filament and subsequently melted or evaporated in reverse flow, with the velocity adjusted for appropriate fall speed to reproduce conditions of the melting layer. Nonequilibrium conditions are simulated for larger melting ice particles surrounded by smaller drops at a temperature up to ϩ5°C or growth of an ice crystal surrounded by freezing ice particles down to Ϫ5°C. Initial melting of well-defined faceted crystals, as individuals or in combination, occurs as a water layer Ͼ10 m thick. For larger (Ͼ100 m) crystals the water becomes sequestered by capillary forces as individual drops separated by water-free ice regions, often having quasiperiodic locations along needles, columns, or arms from evaporating den- drites. Drops are also located at intersections of aggregate crystals and dendrite branches, being responsible for the maximum of the radar scatter. The drops have a finite water–ice contact angle of 37°–80°, depending on ambient conditions. Capillary forces move water from high-curvature to low-curvature regions as melting continues. Toward the end of the melting process, the ice separating the drops becomes sufficiently thin to fracture under aerodynamic forces, and mixed-phase particles are shed. -

Improved 20-32 Ghz Atmospheric Absorption Model Version June 1, 1998

Improved 20-32 GHz Atmospheric Absorption Model Version June 1, 1998 Sandra L. Cruz Pol, Christopher S. Ruf Communications and Space Science Laboratory, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA Stephen J. Keihm Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA Abstract. An improved model for the absorption of the atmosphere near the 22 GHz water vapor line is presented. The Van-Vleck-Weisskopf line shape is used with a simple parameterized version of the model from Liebe for the water vapor absorption ground truth for comparison with in situ radiosonde derived brightness temperatures under clear sky conditions. Estimation of the new model’s four parameters, related to water vapor line strength, line width and continuum absorption, and far-wing oxygen absorption, was performed using the Newton-Raphson inversion method. Improvements to the water vapor line strength and line width parameters are found to be statistically significant. The accuracy of the new absorption model is estimated to be 3% between 20 and 24 GHz, degrading to 8% near 32 GHz. In addition, the Hill line shape asymmetry ratio was evaluated on several currently used models to show the agreement of the data with Van-Vleck-Weisskopf based models, and rule out water vapor absorption models near 22 GHz given by Waters and Ulaby, Moore and Fung which are based on the Gross line shape. 1. Introduction [Keihm et al., 1995] and GEOSAT Follow-on Water Vapor Radiometer [Ruf et al., 1996], VLBI geodetic bsorption and emission by atmospheric gases can measurements [Linfield et al., 1996], and the significantly attenuate and delay the propagation tropospheric calibration effort planned for the A of electromagnetic signals through the Earth’s Cassini Gravitational Wave Experiment [Keihm and atmosphere. -

Twelve Lectures on Cloud Physics

Twelve Lectures on Cloud Physics Bjorn Stevens Winter Semester 2010-2011 Contents 1 Lecture 1: Clouds–An Overview3 1.1 Organization...........................................3 1.2 What is a cloud?.........................................3 1.3 Why are we interested in clouds?................................4 1.4 Cloud classification schemes..................................5 2 Lecture 2: Thermodynamic Basics6 2.1 Thermodynamics: A brief review................................6 2.2 Variables............................................8 2.3 Intensive, Extensive, and specific variables...........................8 2.3.1 Thermodynamic Coordinates..............................8 2.3.2 Composite Systems...................................8 2.3.3 The many variables of atmospheric thermodynamics.................8 2.4 Processes............................................ 10 2.5 Saturation............................................ 10 3 Lecture 3: Droplet Activation 11 3.1 Supersaturation over curved surfaces.............................. 12 3.2 Solute effects.......................................... 14 3.3 The Kohler¨ equation and its properties............................. 15 4 Lecture 4: Further Properties of an Isolated Drop 16 4.1 Diffusional growth....................................... 16 4.1.1 Temperature corrections................................ 18 4.1.2 Drop size effects on droplet growth.......................... 20 4.2 Terminal fall speeds of drops and droplets........................... 20 5 Lecture 5: Populations of Particles 22 5.1 -

Micrometeorological Measurements at Ash Meadows and Corn Creek Springs, Nye and Clark Counties, Nevada, 1986-87

Micrometeorological Measurements at Ash Meadows and Corn Creek Springs, Nye and Clark Counties, Nevada, 1986-87 By Michael J. Johnson U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 92-650 Prepared in cooperation with the STATE OF NEVADA Carson City, Nevada 1993 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Robert M Hirsch, Acting Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Government. For additional information Copies of this report may be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Earth Science Information Center 333 West Nye Lane, Room 203 Open-File Reports Section Carson City, NV 89706-0866 Box 25425, MS 517 Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225-0046 CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT .............................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .......................................................... 1 DATA COLLECTION ....................................................... 4 Equipment used ....................................................... 4 Equipment maintenance ................................................. 5 DATA PROCESSING ....................................................... 7 Field-data file formats .................................................. 7 Equations used ....................................................... 9 Eddy-correlation method ........................................... 9 Penman-combination method ....................................... -

George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama

NASA TECHNICAL MEMORC-NDUM NASA lM-82392 .4N EXTENDED CLASS I CAL SOLUTION OF THE DROPLET GROWTH PROBLEM (USA-Tn-82392) All LTBPDED CLASSiCAL bi81- 173112 SOLIITIOU OF TUB DROPLET CBOYTH PROBLEM (UASA) 49 p tic AO3/8i? A01 CSCL 200 Uncl as G3/34 41425 By B . Jeffrey Anderson, John Hallett , and Maurice Beesley January 1981 NASA George C. Marshall Space Flight Center Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama mFC - ?om 3190 (Rev Juw 1971) lo. wotk urn? NO. George C, Marshall Space Flight Center Marehall. Space Flight Center, Alabama 35812 t1 1. CWRAtT 011 6RAW NO. 19. tm or arm. s rrnloo covmu I2 SCOWSOI)ING AGENCY NAME AM0 AOOMII National Aeronautics and Space Administration Technical Memorandum Washington, D. C , 20546 14. SPONSORING AGaNCY CODE IS. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTLS *Desert Research Institute, Univer~ityof Nevada System, Reno, Nevada 89507 **Department of Mathematics, University of Nevada System, Reno, Nevada 89507 Prepared by Space Sciences Laboratory, Science and Engineering Directorate 16. ABSTRACT Problems of applying the classical kinetic theory to tile growth of small droplets from the vapor are examined. A solution for the droplet growth equa- tion is derived which is based on the assumption of a diffusive field extending to the drop sul:face. The method accounts for partial thermal and mass accommo- dation at the interface and the kinetic limit to the mass and heat fluxes, and it avoids introducing the artifact of a discontinuity in the thermal and vapor field near the droplet. Consideration of the environmental fields in spherical geometry utilizing directional fluxes yields boundary values in terms of known parameters and a new Laplace transform integral. -

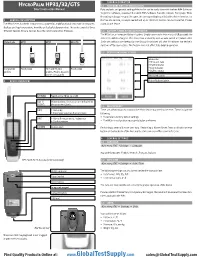

Manual Data Analysis, and General Setting of the Device Can Be Easily Done with the Free HW4 Software

3 GENERAL OPERATION HYGROPALM HP31/32/GTS 3.1 SOFTWARE HW4 LITE INSTALLATION Short Instruction Manual Data analysis, and general setting of the device can be easily done with the free HW4 Software. To get the software, download the latest HW4 Software from the Rotronic Homepage. While the software always remains the same, the corresponding key unlocks the desired version. For 1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION the free Lite version, no key is needed and up to 3 Rotronic devices can be connected. Probes The HP3x-Series handheld instrument is a power full, multifunctional device which measures, count as one device. displays and logs temperature, humidity and calculated parameters. The series consist of three different devices. Ensure devices have the latest compatible firmware. 3.2 BATTERY, STAND-BY AND AUTO SWITCH The HP3x has an integrated lithium battery. Simply connect the device to an USB port with the delivered cable to charge it. The device has a stand-by and an auto switch off feature. After Order Code HP31 HP32 HP-GTS 5 minutes without user interaction the display is switched off, after 10 minutes the device is switched off to save battery. This feature does not affect data logging operation. 3.3 DISPLAY AND HOME SCREEN Status Bar • Time and date • Hold indicator Compatible Fixed probe HC2 and HC2A-S Fixed probe • Log indicator probes probes. Probes must be • Battery status ordered separately Measured values 2 DEVICE OVERVIEW Action Buttons labels [POWER] Switches the HP32 on or off. [LEFT] Action buttons, their action are indicated by [RIGHT] the on-screen labels. -

Stability and Exchange of Subsurface Ice on Mars

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 110, E05003, doi:10.1029/2004JE002350, 2005 Stability and exchange of subsurface ice on Mars Norbert Schorghofer and Oded Aharonson Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA Received 19 August 2004; revised 1 February 2005; accepted 17 March 2005; published 5 May 2005. [1] We seek a better understanding of the distribution of subsurface ice on Mars, based on the physical processes governing the exchange of vapor between the atmosphere and the subsurface. Ground ice is expected down to 49° latitude and lower latitudes at poleward facing slopes. The diffusivity of the regolith also leads to seasonal accumulation of atmospherically derived frost at latitudes poleward of 30°. The burial depths and zonally averaged boundaries of subsurface ice observed from neutron emission are consistent with model predictions for ground ice in equilibrium with the observed abundance of atmospheric water vapor. Longitudinal variations in ice distribution are due mainly to thermal inertia and are more pronounced in the observations than in the model. These relations support the notion that the ground ice has at least partially adjusted to the atmospheric water vapor content or is atmospherically derived. Changes in albedo can rapidly alter the equilibrium depth to the ice, creating sources or sinks of atmospheric H2O while the ground ice is continuously evolving toward a changing equilibrium. At steady state humidity and temperature oscillations, the net flux of vapor is uninhibited by adsorption. The occurrence of temporary frost is characterized by the isosteric enthalpy of adsorption. Citation: Schorghofer, N., and O. -

Weather and Evapotranspiration Studies in a Saltcedar Thicket, Arizona

Weather and Evapotranspiration Studies in a Saltcedar Thicket, Arizona G E 0 L 0 G I CAL SURVEY P R 0 FE S S I 0 N A L PAPER 4 9 1-F Weather and Evapotranspiration Studies in a Saltcedar Thicket, Arizona By T. E. A. VAN HYLCKAMA STUDIES OF EVAPOTRANSPIRATION G E 0 L 0 G I CAL SURVEY P R 0 FE S S I 0 N A L PAPER 4 9 1-F U N I T E D STATES G 0 V ERN M EN T P R I N T I N G 0 F F I C E, WAS H I N G T 0 N 1 9 8 0 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Van Hylckama, T. E. A. Weather and evapotranspiration studies in a saltcedar thicket, Arizona. (Studies of evapotranspiration) (Geological Survey professional paper; 491-F) Bibliography: p. F48-F51. 1. Tamarix Chinensis. 2. Evapotranspiration-Arizona-Buckeye region. 3. Vegetation and climate-Arizona-Buckeye region. 4. Microclimatology-Arizona-Buckeye region. 5. Phreatophytes Arizona-Buckeye region. I. Title. II. Series. Ill. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper; 491-F. QE75.P9 no. 491-F [QK495.T35] 557.3s 80-11316 [583'.158] For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Instrumentation-Continued Page Abstract __ ___ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ _ _ _ _ __ __ __ _ __ _ __ __ ____ _ _ _ F1 Radiation ____________________________________ ---_______ F19 Introduction________________________________________________ 1 Soil temperature, heat flow, and soil moisture ____________ 20 Saltcedar -

Download Paroc Moisture Guide

MOISTURE GUIDE PAROC STONE WOOL CONTENT: 1. Moisture 1.1. Moisture transport mechanisms 3 1.1.1. Bulk moisture and building moisture 3 1.1.2. Convection 3 1.1.3. Diffusion 5 1.1.4. Capillarity 6 1.2. Myth of ”Breathing structures” 6 1.2.1. Air leakage 6 1.2.2. Moisture buffering of indoor air humidity 6 2. Moisture and building envelope design 2.1. Foundation 7 2.2. Frost and floor insulation 9 2.3. External walls 11 2.4. Roof 14 2.5. Eaves and roof drainage systems 15 2.6. Design details (joints, flashings and other connections)) 15 2.7. Air ventilation & Plumbing 16 3. Moisture risks 3.1. Corrosion 17 3.2. Mold 17 3.3. Loss of performance 18 4. Mold calculation for most typical constructionst 19 5. Moisture properties of Paroc stone wool 5.1. Moisture properties 23 5.2. Air and moisture control 25 6. Importance of Dry chain in building process 26 Moisture guide Paroc stone wool 1. MOISTURE We are surrounded with water. It covers 71% of the Building moisture is the excessive moisture Earth’s surface and is vital for all known forms of life. subjected to building materials during their manufac- Water is present in the form of solid, liquid or gas. turing process, storing or installation. This moisture The sun’s heat recycles our planet’s water as it aims to evaporate or dry during the construction evaporates into the atmosphere from the oceans, process and building use. Building moisture is the lakes, soil, people and vegetation.