Gaming As a Literacy Practice Amy Conlin Hall Dissertation Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

364 Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on The

Journal of Social Studies Education Research Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2019:10 (3),364-386 www.jsser.org Gaminguistics: Proposing a Framework on the Communication of Video Game Avatars Giyoto Giyoto1, SF. Luthfie Arguby Purnomo2, Lilik Untari3, SF. Lukfianka Sanjaya Purnama4 & Nur Asiyah5 Abstract This study attempts to construct a communication framework of video game avatars. Employing Aarseth’s textonomy, Rehak’s avatar’s life cycle, and Lury’s prosthetic culture avatar’s theories as the basis of analysis on fifty-five purposively selected games, this study proposes ACTION (Avatars, Communicators, Transmissions, Instruments, Orientations and Navigations). Avatars, borrowing Aarseth’s terms, are classifiable into interpretive, explorative, configurative, and textonic with four systems and sub classifications for each type. Communicators, referring to the participants involved in the communication with the avatars and their relationship, are classifiable into unipolar, bipolar, tripolar, quadripolar, and pentapolar. Transmissions, the ways in which communication is transmitted, are classifiable into restrictive verbal and restrictive non-verbal. Instruments, the graphical embodiment of communications, are realized into dialogue boxes, non-dialogue boxes, logs, expressions, movements and emoticons. Orientations, the methods the game spatiality employs to direct the movement of the avatars, are classifiable into dictative and non-dictative. Navigations, the strategies avatars perform regarding with the information saving system of the games, are classifiable into experimental and non-experimental. Departing from this ACTION, analysts are able to employ this formula as an approach to reveal how the avatars utilize their own ‘linguistics’ to communicate, out of the linguistics benefited by humans. Keywords: framework of communication, game avatars, game studies, video games, prosthetic culture. -

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

Video Game Collection MS 17 00 Game This Collection Includes Early Game Systems and Games As Well As Computer Games

Finding Aid Report Video Game Collection MS 17_00 Game This collection includes early game systems and games as well as computer games. Many of these materials were given to the WPI Archives in 2005 and 2006, around the time Gordon Library hosted a Video Game traveling exhibit from Stanford University. As well as MS 17, which is a general video game collection, there are other game collections in the Archives, with other MS numbers. Container List Container Folder Date Title None Series I - Atari Systems & Games MS 17_01 Game This collection includes video game systems, related equipment, and video games. The following games do not work, per IQP group 2009-2010: Asteroids (1 of 2), Battlezone, Berzerk, Big Bird's Egg Catch, Chopper Command, Frogger, Laser Blast, Maze Craze, Missile Command, RealSports Football, Seaquest, Stampede, Video Olympics Container List Container Folder Date Title Box 1 Atari Video Game Console & Controllers 2 Original Atari Video Game Consoles with 4 of the original joystick controllers Box 2 Atari Electronic Ware This box includes miscellaneous electronic equipment for the Atari videogame system. Includes: 2 Original joystick controllers, 2 TAC-2 Totally Accurate controllers, 1 Red Command controller, Atari 5200 Series Controller, 2 Pong Paddle Controllers, a TV/Antenna Converter, and a power converter. Box 3 Atari Video Games This box includes all Atari video games in the WPI collection: Air Sea Battle, Asteroids (2), Backgammon, Battlezone, Berzerk (2), Big Bird's Egg Catch, Breakout, Casino, Cookie Monster Munch, Chopper Command, Combat, Defender, Donkey Kong, E.T., Frogger, Haunted House, Sneak'n Peek, Surround, Street Racer, Video Chess Box 4 AtariVideo Games This box includes the following videogames for Atari: Word Zapper, Towering Inferno, Football, Stampede, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Ms. -

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline 3 Related Market Data Group Organization Toys and Hobby 01 Overview of Group Organization 20 Toy Market 21 Plastic Model Market Results of Operations Figure Market 02 Consolidated Business Performance Capsule Toy Market Management Indicators Card Product Market 03 Sales by Category 22 Candy Toy Market Children’s Lifestyle (Sundries) Market Products / Service Data Babies’ / Children’s Clothing Market 04 Sales of IPs Toys and Hobby Unit Network Entertainment 06 Network Entertainment Unit 22 Game App Market 07 Real Entertainment Unit Top Publishers in the Global App Market Visual and Music Production Unit 23 Home Video Game Market IP Creation Unit Real Entertainment 23 Amusement Machine Market 2 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Amusement Facility Market History 08 BANDAI’s History Visual and Music Production NAMCO’s History 24 Visual Software Market 16 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Music Content Market IP Creation 24 Animation Market Notes: 1. Figures in this report have been rounded down. 2. This English-language fact book is based on a translation of the Japanese-language fact book. 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline GROUP ORGANIZATION OVERVIEW OF GROUP ORGANIZATION Units Core Company Toys and Hobby BANDAI CO., LTD. Network Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Real Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Inc. Visual and Music Production BANDAI NAMCO Arts Inc. IP Creation SUNRISE INC. Affiliated Business -

Analysis of Innovation in the Video Game Industry

Master’s Degree in Management Innovation and Marketing Final Thesis Analysis of Innovation in the Video Game Industry Supervisor Ch. Prof. Giovanni Favero Assistant Supervisor Ch. Prof. Maria Lusiani Graduand Elena Ponza Matriculation number 873935 Academic Year 2019 / 2020 I II Alla mia famiglia, che c’è stata quando più ne avevo bisogno e che mi ha sostenuta nei momenti in cui non credevo di farcela. A tutti i miei amici, vecchi e nuovi, per tutte le parole di conforto, le risate e la compagnia. A voi che siete parte di me e che, senza che vi chieda nulla, ci siete sempre. Siete i miei fiorellini. Senza di voi tutto questo non sarebbe stato possibile. Grazie, vi voglio bene. III IV Abstract During the last couple decades video game consoles and arcades have been subjected to the unexpected, swift development and spread of mobile gaming. What is it though that allowed physical platforms to yet maintain the market share they have over these new and widely accessible online resources? The aim of this thesis is to provide a deeper understanding of the concept of innovation in the quickly developing world of video games. The analysis is carried out with qualitative methods, one based on technological development in the context of business history and one on knowledge exchange and networking. Throughout this examination it has been possible to explore what kind of changes and innovations were at first applied by this industry and then extended to other fields. Some examples would be motion control technology, AR (Augmented Reality) or VR (Virtual Reality), which were originally developed for the video game industry and eventually were used in design, architecture or in the medical field. -

Star Fox Adventures: Da Dinosaur Planet Al Prodotto Finale

Star Fox Adventures: da Dinosaur Planet al prodotto finale Sbaglio o ultimamente qui su Dusty Rooms, fra Thunder Force e Ikaruga, abbiamo un po’ la testa fra le nuvole? Che scendere dalle nostre navicelle da combattimento sia la cosa più saggia da fare? Oggi vi racconteremo dello sviluppo di un gioco molto controverso, sviluppato nell’arco di molti anni e arrivato al pubblico con sembianze totalmente diverse da quelle originali e che compromise il solidissimo rapporto fra Nintendo e Rare, facendo diventare quest’ultima compagnia un’esclusiva di Microsoft. Visto il suo 16esimo anniversario dell’uscita (che ricorreva due giorni fa), oggi parleremo di Star Fox Adventures, un gioco dai giudizi contrastanti e che ricordò al mondo che è meglio che Fox McCloud rimanga all’interno del suo Arwing – o magari che scenda solo per prendere a cazzotti i suoi colleghiNintendo per il Super Smash Bros. corrente. Dunque, la risposta alla nostra precedente domanda è semplicemente: NO! Uno standard troppo alto Nel 1997 arriva Star Fox 64 (Lylat Wars in Europa), reboot del già ottimo Star Fox uscito nel 1993 su Super Nintendo, un gioco che riprendeva in parte molti assett diStar Fox 2, titolo essenzialmente pronto già allora ma che vide solo nel 2017 un rilascio ufficiale sulloSnes Classic Mini. Il gioco uscito in bundle colrumble pack, feature che diventò uno standard per la costruzione dei controller nell’industria videoludica, diventò incredibilmente popolare e, fino alla fine dei giorni del Nintendo 64, rimase uno dei titoli di bandiera della console; -

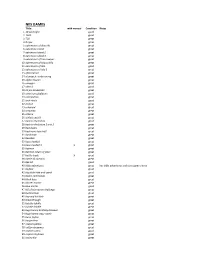

PRGE Nes List.Xlsx

NES GAMES Tittle with manual Condition Notes 1 10 yard fight good 2 1943 great 3 720 great 4 8 eyes great 5 adventures of dino riki great 6 adventure island great 7 adventure island 2 great 8 adventure island 3 great 9 adventures of tom sawyer great 10 adventures of bayou billy great 11 adventures of lolo good 12 adventures of lolo 2 great 13 after burner great 14 al unser jr. turbo racing great 15 alpha mission great 16 amagon great 17 alien 3 good 18 all pro basketball great 19 american gladiators good 20 anticipation great 21 arch rivals good 22 archon great 23 arkanoid great 24 astyanax great 25 athena great 26 athletic world great 27 back to the future good 28 back to the future 2 and 3 great 29 bad dudes great 30 bad news base ball great 31 bards tale great 32 baseball great 33 bases loaded great 34 bases loaded 3 X great 35 batman great 36 batman return of joker great 37 battle toads X great 38 battle of olympus great 39 bee 52 good 40 bible adventures great has bible adventures exclusive game sleeve 41 bigfoot great 42 big birds hide and speak good 43 bionic commando great 44 black bass great 45 blaster master great 46 blue marlin good 47 bill elliots nascar challenge great 48 bomberman great 49 boy and his blob great 50 breakthrough great 51 bubble bobble great 52 bubble bobble great 53 bugs bunny birthday blowout great 54 bugs bunny crazy castle great 55 burai fighter great 56 burgertime great 57 caesars palace great 58 california games great 59 captain comic good 60 captain skyhawk great 61 casino kid great 62 castle of dragon great 63 castlvania great 64 castlvania 2 great 65 castlvania 3 great 66 caveman games great 67 championship bowling great 68 chessmaster great 69 chip n dale great 70 city connection great 71 clash at demonhead great 72 concentration poor game is faded and has tears to front label (tested) 73 cobra command great 74 cobra triangle great 75 commando great 76 conquest of crystal palace great 77 contra great 78 cybernoid great 79 crystal mines X great black cartridge. -

Samantha Losben

Losben 1 Samantha Losben Handling Complex Media April 19, 2011 Assignment #1 Preserving Nintendo’s Duck Hunt In the mid 1980s, home video game systems began to revitalize after the game market crash of 1983 as a result of over saturation of the market. One of the leading game systems to emerge afterwards was the Japanese company Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Nintendo became a fan favorite with the introduction of popular games such as Super Mario Bros., Legend of Zelda, Paperboy, Donkey Kong, and many more. Several popular games were spin-offs of other games, for instance Donkey Kong led to a Super Mario Bros spin-off. Some games were sold as combinations, giving players an option to play different games on the same cartridge. One such popular “bonus game” was Duck Hunt, which was originally featured as a “B-Side” game on the original Super Mario Bros., which was often included with the original NES console. However, Duck Hunt was a unique game, which required additional hardware. Throughout the later part of the 20th century and early 21st century, gaming systems continued to advance. NES, along with its competitors such as Sony Playstation and Sega introduced several models and different generations. Nintendo introduced Super Nintendo, Nintendo 64, and most recently Nintendo Wii. Several classic and popular games from the original NES were re-introduced or re-imagined on the newer consoles; however, some games remain only a memory to the gaming fan base. Duck Hunt was a unique game that is physically attached to the original NES. As a unique gaming experience that was never truly Losben 2 replicated, Duck Hunt is a historic game experience that needs to be preserved. -

001 300 500 002 40 60 003 150 200 004 120 150 005 200

001 Magnavox Odyssey - USA, 1972 Edition assemblée au Mexique, complète en très bon état avec les deux manettes, les layers, les 6 cartes de jeux et notices. Très bel état. Pour rappel, la Magnavox Odyssey est la première console de jeu. 300 500 002 Magnavox Odyssey 4000 - USA, 1977 En boite avec ses câbles 40 60 003 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 6 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-6V #9800 Première console PONG de Nintendo n°4158465 Fourni en boite (bon état) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Bel ensemble des débuts de Nintendo. 150 200 004 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME 15 - JAPON, 1977 Model CTG-15S #15000 Seconde console PONG de Nintendo, sorti peu de temps après la CTG-6V, elle contient 15 jeux. n°2156926 Fourni en boite (abimé sur le dessous) avec câble, switch box et documentation. Trois modèles de couleur sont sortis : Jaune, Orange et Blanc. Cet exemplaire est un modèle jaune. 120 150 005 NINTENDO Color TV-GAME "Racing 112" - JAPON, 1978 En boite et notice, complet, proche du neuf, superbe pièce. Model CTG-CR112 # 5000 n°1021935 200 300 006 PONG SHG "Black Point" Type FS 1003 (1981) Console PONG Allemande programmable à cartouches, livrée en boite avec câbles et deux controllers. 20 40 007 PONG MONTEVERDI "E&P model EP500" TV Sports 825 (1976) Livré en boite, ce PONG très rare licencié par Magnavox est complet avec ses câbles, notice US et Française model n°E825A Series n° 255B Serial n°129956 60 80 008 PONG "SONESTA hide-away TV Game" (1977) En boite avec cale et câble 20 40 009 PONG International LLOYD'S TV Sports 812 (1976) En boite avec fusil, câbles et notice US + française (RARE) Belle chance d'acquérir une pièce historique. -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Nintendo NES Price Guide

Website GameValueNow.com Console Nintendo NES Last Updated 2018-09-30 07:00:07.0 Nintendo NES Price Guide # Title Loose Price Complete Price New Price VGA Price 1. 10-Yard Fight $2.35 $18.05 $772.08 NA 2. 10-Yard Fight [5 Screw] $2.29 $32.16 NA NA 3. 1942 $11.20 $33.32 $684.75 $1500.00 4. 1942 [5 Screw] $10.93 $28.50 NA NA 5. 1943: The Battle of Midway $11.21 $33.80 $172.88 $323.43 6. 3-D World Runner $5.07 $33.22 $80.93 NA 7. 3-D World Runner [5 Screw] $6.64 NA NA NA 8. 6 in 1: Caltron $294.56 $362.95 $419.87 $495.34 9. 6 in 1: Myriad $1239.38 $2795.99 $4505.95 NA 10. 720 $3.39 $11.25 $41.71 $89.39 11. 8 Eyes $6.77 $25.47 $116.39 $78.58 12. A Boy and His Blob: Trouble on Blobolonia, David Crane's $8.13 $32.71 $101.67 $273.35 13. A Nightmare on Elm Street $33.38 $115.09 $457.18 $521.21 14. Abadox: The Deadly Inner War $4.97 $22.53 $52.98 $137.83 15. Action 52 $189.90 $290.13 $496.41 $746.00 16. Addams Family $9.42 $38.52 $95.24 $425.92 17. Addams Family: Pugsley's Scavenger Hunt $39.06 $119.11 $253.04 NA 18. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Dragon Strike $30.87 $88.80 $165.02 $475.99 19. Advanced Dungeons & Dragons: Heroes of the Lance $9.88 $28.52 $135.92 $188.31 20.