An Inquiry Into Staking Agreements As Securities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WPT Festa Al Lago: Cole in Pole – Deeb Und Ferguson in Top 10

WPT Festa al Lago: Cole in Pole – Deeb und Ferguson in Top 10 Von M. W. Im Rennen um die vier Millionen Dollar Preisgeld wird e simmer spannender. Corwin Cole holte sich die Pole-Position und ist mit knapp einer Million Chips Favorit auf den Titel, der mit 1.218.225 Dollar belohnt wird. Von den 96 Teilnehmern sind noch 37 im Turnier. Heute müssen noch zehn davon raus, damit sich die restlichen Spieler ein Preisgeld von mindestens 23.855 Dollar abholen können. Freddy Deeb und Chris Ferguson stiegen dank einer Sonderregelung erst am gestrigen zweiten Tag in die Veranstaltung ein und liegen bereits auf dem achten und zehnten Platz. Für Chris „Jesus“ Ferguson sah es kurz gar nicht gut aus, als er und sein Gegenüber auf dem Board von D710/9 All-In gingen. Es selbst hatte zwar die Dame zum High- Pair, doch auf der anderen Seite zeigte sich D/9 für zwei Paare. Ferguson muss allerdings einen Schutzengel gehabt haben, denn schon am Turn folgte der König. Der Gewinner der 2009 Legends of Poker Prahlad Friedman liegt mit 188.000 im hinteren Feld. Seine Ehefrau führt ihm derzeit vor, wie es besser ginge. Dee Luong (Bild) liegt nämlich mit 771.500 Chips auf dem ausgezeichneten vierten Platz und ist natürlich die beste Frau im Event. Für Tag 1-Chipleader Mike Matusow, Justin Bonomo, Jonathan Little, Scott Clements und Mike Leah ist die WPT Festa al Lago bereits gelaufen. Corwin Cole schmiss kurz vor Ende Bob Safai, der ein Paar Neuner hielt, hinaus. Cole callte mit A/J und sah am Flop eben diese zwei Karten in einer anderen Farbe auftauchen. -

MJ GONZALES: Ankush Mandavia Talks DANIEL NEGREANU’S About Triumphant Return to Live COACH SEEKS out Tournament Circuit

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 9 April 21, 2021 MJ GONZALES: Ankush Mandavia Talks DANIEL NEGREANU’S About Triumphant Return To Live COACH SEEKS OUT Tournament Circuit HEADS-UP ACTION Twitch Streamer Vanessa Kade Gets Last OF HIS OWN Laugh, Wins Sunday High-Stakes Pro Talks Upcoming Million For $1.5M $3M Freezeout, Private Games, And New Coaching Platform Tournament Strategy: Position And Having The Lead PLAYER_34_08_Cover.indd 1 3/31/21 9:29 AM PLAYER_08_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 3/16/21 9:39 AM PLAYER_08_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 3/16/21 9:39 AM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 9 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. -

Matt Hawrilenko Siegt Beim World Series of Poker Event #56 – USD 5,000 Six-Handed No Limit Hold’Em

Matt Hawrilenko siegt beim World Series of Poker Event #56 – USD 5,000 Six-handed No Limit Hold’em Matt „Hoss_TBF“ Hawrilenko geht als Nummer 1 bei einem Teilnehmerfeld von insgesamt 928 Spielern hervor. Nach Dutzenden WSOP Cashes und vier Finaltischen hat er nun sein heissersehntes WSOP Gold Bracelet gewonnen und ein sagenhaftes Preisgeld Matt Hawrilenko (Bildquelle: PokerNews.com) von USD 1,003,163. Zweiter wurde Josh Brikis der für seine Platzierung USD 619,609 erhielt. Es wurden im Heads Up Match nur vier Hände gespielt. Die vierte war bereits die Entscheidende. Die Finale Hand: Josh Brikis raiste auf 300,000 vom Small Blind, Matt Hawrilenko reraiste auf 1 Million, Brikis ging all in und Hawrilenko callte. Showdown: Brikis: A [key:card_diamonds] 9 [key:card_diamonds] Hawrilenko: J [key:card_hearts] J [key:card_diamonds] Das Board war 2 [key:card_hearts] 8 [key:card_clubs] 8 [key:card_diamonds] 3 [key:card_spades] 10 [key:card_clubs], dies bedeutete den Sieg für Matt Hawrilenko und als Runner Up ging Josh Brikis hervor. Wie zu erwarten war das Teilnehmerfeld mit Poker Pros dicht bestickt. Darunter sah man unter anderen Shannon Shorr, John Duthie, Juha Helppi, Gavin Griffin, Andy Black, Chris Ferguson, Eli Elezra, Barry Shulman, Matt Graham, Vicky Coren, Marc Naalden, Noah Boeken, Bertrand „ElkY“ Grospellier, Vanessa Rousso, Jennifer Tilly, Scotty Nguyen, Daniel Alaei, Dave Ulliott, Jamie Gold, Tony G, Erik Lindgren, Brandon Cantu, David „Chino“ Rheem, Dario Minieri, Justin Bonomo, Dennis Phillips, Roland de Wolfe, Erich Froehlich, Mike Caro, Marco Traniello, Antonio Esfandiari, Nenad Medic, T.J. Cloutier, Jason Mercier, Gavin Smith, Kirill Gerasimov, Florian Langmann, Ivan Demidov, Allen Cunningham, Daniel Negreanu, Barny Boatman und Isaac Haxton. -

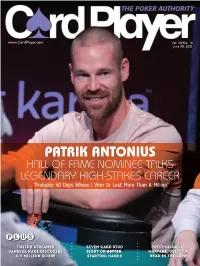

PATRIK ANTONIUS HALL of FAME NOMINEE TALKS LEGENDARY HIGH-STAKES CAREER “Probably 40 Days Where I Won Or Lost More Than a Million”

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 14 June 30, 2021 PATRIK ANTONIUS HALL OF FAME NOMINEE TALKS LEGENDARY HIGH-STAKES CAREER “Probably 40 Days Where I Won Or Lost More Than A Million” Twitch Streamer Seven Card Stud Psychological Vanessa Kade Discusses Eight-Or-Better: Warfare: Get Your $1.5 Million Score Starting Hands Head In The Game PLAYER_34_14B_Cover.indd 1 6/10/21 10:41 AM PLAYER_14_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 6/7/21 8:30 PM PLAYER_14_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 6/7/21 8:30 PM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 14 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. -

Poker Face Profiles the Irish Superstars Leading the Goldrush to Vegas PAGE 5

SPaturday, May 28, 2O011 KER FACE POKER FACE THE IRISH RACING P OST ... exclusively for the Irish poker player Young online wizard Jono Crute speaks about his short but distinguished career to date PAGE 9 John O’Shea reveals his monster bets in this month’s unmissable diary PAGE 11 BRACELET HUNTERS Poker Face profiles the Irish superstars leading the goldrush to Vegas PAGE 5 FEEL THE RUSH. YOU’LL NEVER PLAY POKER THE SAME WAY AGAIN. LEARN, CHAT AND PLAY WITH THE PROS 100% SIGN-UP BONUS UP TO $600* 6HHZHEVLWHIRUGHWDLOV(QMR\WKHIUHHJDPHVDQGEHIRUHSOD\LQJLQWKHUHDOPRQH\JDPHVSOHDVHFKHFNZLWK\RXUORFDOMXULVGLFWLRQUHJDUGLQJWKHOHJDOLW\RI,QWHUQHWSRNHU)XOO7LOW3RNHU$OOULJKWVUHVHUYHGZZZJDPEOHDZDUHFRXN THE IRISH RACING P OST PULL-OUT FREE WITH THE ON THE LAST SATURDAY OF EACH MON TH 2 POKER FACE Saturday, May 28, 2011 racingpost.com POKER NEWS Seiver and Seidel scoop PokerView introduces webcam cash games By Ken Powell depositing players. top Bellagio honours For players who don’t yet feel up to ONLINE poker players can finally see playing face-to-face with their By Ken Powell the rest of his stack with two pair and from the small blind, and Erick who they’re raising and stare down opponents, standard avatar tables are sealed his victory. For the win, Seiver Lindgren, 34, checked his option in the rivals who go all-in. also available. OHIO poker phenomenon Scott Seiver banked a total of $1,618,344, bringing big blind. The flop fell Ac4c2c, and By introducing webcam tables earlier PokerView has been developing its took down the prestigious$25,000 his career earnings to $4.5 million. -

Daniel Negreanu Breaks 7-Year Title Drought to Win the Inaugural Pokergo Cup Hall of Famer Says His Poker Game Is Better Than Ever

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 34/No. 18 August 25, 2021 Daniel Negreanu Breaks 7-Year Title Drought To Win The Inaugural PokerGO Cup Hall Of Famer Says His Poker Game Is Better Than Ever SixTime Bracelet WSOP Champ Greg Tournament Strategy: Winner Layne Flack Raymer Explains How To Street By Street Passes Away Prep For The Main Event Bet Sizing PLAYER_34_17B_Cover.indd 1 8/3/21 11:13 AM PLAYER_17_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 7/19/21 3:58 PM PLAYER_17_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 7/19/21 3:58 PM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 34/No. 18 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman Editorial Corporate Office EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi Schedules FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener [email protected] Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117. -

The Biggest Bluff : How I Learned to Pay Attention, Master the Odds, and Win / Maria Konnikova

ALSO BY MARIA KONNIKOVA The Confidence Game Mastermind PENGUIN PRESS An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Maria Konnikova Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Names: Konnikova, Maria, author. Title: The biggest bluff : how I learned to pay attention, master the odds, and win / Maria Konnikova. Description: New York : Penguin Press, 2020. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020002627 (print) | LCCN 2020002628 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525522621 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525522638 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Konnikova, Maria. | Seidel, Erik, 1959- | Poker players—United States—Biography. | Women poker players—United States—Biography. | Poker players—Psychology. | Poker—Psychological aspects. | Human behavior. Classification: LCC GV1250.2.K66 A3 2020 (print) | LCC GV1250.2.K66 (ebook) | DDC 795.412—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020002627 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020002628 Jacket images: (Queen of Spades) Getty Images Plus; (card pattern) Mercurio / Shutterstock pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0 In memory of Walter Mischel. I still haven’t published my dissertation, as I promised you I would, but at least there is this. May we always have the clarity to know what we can control and what we can’t. And to my family, for being there no matter what. -

2013 National Heads-Up Poker Championship

2013 NATIONAL HEADS-UP POKER CHAMPIONSHIP Round of 64 Round of 32 Round of 16 Quarterfinals Semifinals Championship Semifinals Quarterfinals Round of 16 Round of 32 Round of 64 January 24th January 25th January 25th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 26th January 25th January 25th January 24th Antonio Esfandiari Joseph Cheong Antonio Esfandiari Joseph Cheong Jennifer Tilly Olivier Busquet Antonio Esfandiari Jean-Robert Bellande Jonathan Duhamel Jean-Robert Bellande Jonathan Duhamel Bruce Miller Matt Glantz Bruce Miller Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Chris Moorman Maria Ho Chris Moorman Phil Galfond Carlos Mortensen Phil Galfond Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Matt Salsberg Eugene Katchalov Daniel Cates Eugene Katchalov Daniel Cates Faraz Jaka Vanessa Rousso Justin Smith Vanessa Rousso Justin Smith Yevgeniy Timoshenko Elky Grospellier Vanessa Rousso Phil Hellmuth Shaun Deeb Phil Hellmuth Shaun Deeb Phil Hellmuth Andy Frankenberger Mike Sexton Scott Seiver Phil Hellmuth Andy Bloch Chris Moneymaker Kyle Julius Chris Moneymaker Kyle Julius Jason Somervile Scott Seiver David Sands Will Failla Rob Salaburu Scott Seiver David Sands Scott Seiver David Sands Ben Lamb Erik Seidel Barry Greenstein CHAMPION Tom Dwan Barry Greenstein Tom Dwan Barry Greenstein Tom Dwan John Monnette Tom Marchese John Monnette Doyle Brunson Greg Raymer Doyle Brunson Mike Matusow Brian Hastings Viktor Blom Brian Hastings Viktor Blom Brian Hastings Andrew Lichtenberger Matt Matros Mike Matusow Brian Hastings Michael Mizrachi Nick Schulman Mike Matusow Eli Elezra Mike Matusow Eli Elezra David Williams Greg Merson John Hennigan Joe Serock John Hennigan Joe Serock John Hennigan Joe Serock Sam Simon Mohsin Charania Sam Simon Huck Seed David Oppenheim Huck Seed John Hennigan Joe Serock Phil Laak Liv Boeree Phil Ivey Gaelle Baumann Phil Ivey Gaelle Baumann Phil Ivey Dan Smith Isaac Haxton Jason Mercier Justin Bonomo Dan Smith Justin Bonomo Dan Smith. -

World Series of Poker to Award 85 Online Bracelets in 2020 Poker World Has Mixed Reaction

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 33/No. 16 July 29, 2020 WORLD SERIES OF POKER TO AWARD 85 ONLINE BRACELETS IN 2020 POKER WORLD HAS MIXED REACTION High-Stakes Poker Pro Preparing For 2020 Dan Smith Talks Online High The World Series of #wouldbeWSOP Rollers And Poker Ecosystem Poker Online Edition PLAYER_33_16_Cover.indd 1 7/9/20 9:14 AM PLAYER_16_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 7/7/20 4:19 PM PLAYER_16_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 7/7/20 4:19 PM SUBSCRIBE TODAY! Visit www.cardplayer.com/link/subscribe or Call 1-866-587-6537 CP_Sub_25_DT.indd 4 7/7/20 4:19 PM SUBSCRIBE TODAY! PRINT + DIGITAL ACCESS ♠ 26 ISSUES PER YEAR ♠ FREE DIGITAL ACCESS ♠ VIEW ARCHIVES OF OVER 800 ISSUES Visit www.cardplayer.com/link/subscribe or Call 1-866-587-6537 CP_Sub_25_DT.indd 5 7/7/20 4:19 PM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 33/No. 16 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Justin Marchand Editorial Corporate Office MANAGING EDITOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] CHIEF MEDIA OFFICER Justin Marchand VP INTL. -

Biggest Casino Whales Macau Makes a Big Move in Manila the Biggest Looking Back at Appt Losing Players Nanjing Millions Shut in Online Down History

MAGAZINE THE WORLD’S POKER KING CLUB BIGGEST CASINO WHALES MACAU MAKES A BIG MOVE IN MANILA THE BIGGEST LOOKING BACK AT APPT LOSING PLAYERS NANJING MILLIONS SHUT IN ONLINE DOWN HISTORY POKER IN ASIA 2015 TWELVE STORIES Contents. These losing players deserve our respect and admiration for their sheer perseverance, and above all else, we should remember that they have always been the pillars upon December 2015 // Biggest Online looser which the world of high stakes poker is balanced January February March April THE WORLD’S BIGGEST PROSTITUTION EIGHT PHIL IVEY POKER KING CLUB CASINO WHALES SCANDALS IN MACAU STORIES MACAU MAKES A BIG MOVE IN MANILA Page 03 Page 05 Page 06 Page 07 May June July August THE APRISIANLESS LOOKING BACK AT APPT INTERVIEW: WALLY “THE DREAM” GAMBLING MORE NANJING MILLIONS SOMBERO FROM ASIAN TERRY FAN ENTERTAINEMENT, IS SHUT DOWN POKER PIONEER TO 2015 A TURNING POINT GAME-CHANGER FOR MACAU? Page 08 Page 10 Page 12 Page 14 September October November December ARE INTERNATIONAL THE LEGEND OF THE BIGGEST LOSING 5 FISHY WAYS TO THINK POKER PLAYERS ISILDUR1 IN 7 DATES PLAYERS IN ONLINE ABOUT POKER CHANGING THE HISTORY FACE OF THE ASIAN POKER SCENE? Page 16 Page 18 Page 20 Page 22 January 2015 Adnan Khashoggi Adnan Khashoggi is a gambler that every casino wants walking through their doors. Having spent years as a businessman reportedly involved in the sale of military hardware such as aircraft and weapons, he became a serious high stakes gambler for over 25 years. At one point his fortune was said to exceed $40billion, but eventually, his cheques began to bounce, and casinos came looking for payment. -

WSOP Tag 4: Affleck Voran – Hellmuth Draußen

WSOP Tag 4: Affleck voran – Hellmuth draußen Michael Wulschnig Nach Tag 4 sind noch 407 Spieler im Rennen um den wichtigsten Preis des Jahres. Die Bubble platzte als Kia Hamadani seine letzten Chips als Blind in die Mitte schob und mit J/4 nichts mehr zu lachen hatte. Nachdem zuvor etwa eine Stunde „Hand for Hand Play“ betrieben wurde, blieb ihm als Trostpreis der Buy- In für den Main Event 2010. Die restlichen 648 Spieler waren somit in den Geldrängen. Auch für einige Poker-Pros ist die diesjährige World Series of Poker gestern zu Ende gegangen. Dazu gehören Greg Mueller, Chris Ferguson, Justin Bonomo und der Mann mit den meisten Bracelets Phil Hellmuth. Letzterer hatte besonders viel Pech, da er mit Pocket Assen All-In ging und gegen eine niedere Straße das Nachsehen hatte. Die Führung erspielte sich Matt Affleck. Er steht im Moment bei 1.819.000 Chips. Bertrand Grospellier, der am Vortag noch ganz oben stand, rutschte auf Rang 16 zurück und liegt damit unmittelbar hinter Phil Ivey. Die beiden besitzten rund 1.200.000 Chips. Den zweiten Rang konnte der Franzose Lacay Ludovic (1.600.000) erfolgreich verteidigen. An sensationeller achter Stelle ist der Österreicher Bernhard Perner mit über 1.400.000 Chips zu finden. Bester Deutscher ist derzeit Tim Kahlmayer, der mit 840.000 auf dem 56 Platz liegt. Unwesentlich weniger Chips hat Christian Heich, der genauso wie Nasr El Nasr noch Titelchancen hat. Für Hans Hein, Rainer Meyer, Alex Jalali, Benjamin Kang und Felix Osterland lebt die Chance ebenfalls weiter, auch wenn es für manche schon eines kleinen Wunders bedarf. -

Seth Davies' Journey from the Dugout to the Highest

www.CardPlayer.com Vol. 33/No. 18 August 26, 2020 70-Year-Old Online Newb Wins WSOP Bracelet On First Try Hand History Rewind: A Look Back At Joe Cada's 2009 WSOP Win Greg Raymer On Being A Lawyer At The Poker Table SETH DAVIES’ JOURNEY FROM THE DUGOUT TO THE HIGHEST STAKES POKER TOURNAMENTS IN THE WORLD How The Oregon Native Saw An Opportunity For Poker Greatness After Repeated Injuries Ended His Baseball Career PLAYER_33_18_Cover.indd 1 8/6/20 9:57 AM PLAYER_18_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 2 8/4/20 10:44 AM PLAYER_18_GlobalPoker_DT.indd 3 8/4/20 10:44 AM Masthead - Card Player Vol. 33/No. 18 PUBLISHERS Barry Shulman | Jeff Shulman ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Justin Marchand Editorial Corporate Office MANAGING EDITOR Julio Rodriguez 6940 O’Bannon Drive TOURNAMENT CONTENT MANAGER Erik Fast Las Vegas, Nevada 89117 ONLINE CONTENT MANAGER Steve Schult (702) 871-1720 Art [email protected] ART DIRECTOR Wendy McIntosh Subscriptions/Renewals 1-866-LVPOKER Website And Internet Services (1-866-587-6537) CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER Jaran Hardman PO Box 434 DATA COORDINATOR Morgan Young Congers, NY 10920-0434 Sales [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Mary Hurbi Advertising Information NATIONAL SALES MANAGER Barbara Rogers [email protected] LAS VEGAS AND COLORADO SALES REPRESENTATIVE (702) 856-2206 Rich Korbin Distribution Information cardplayer Media LLC [email protected] CHAIRMAN AND CEO Barry Shulman PRESIDENT AND COO Jeff Shulman Results GENERAL COUNSEL Allyn Jaffrey Shulman [email protected] CHIEF MEDIA OFFICER Justin Marchand VP INTL. BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT Dominik Karelus Schedules CONTROLLER Mary Hurbi [email protected] FACILITIES MANAGER Jody Ivener Follow us www.facebook.com/cardplayer @CardPlayerMedia Card Player (ISSN 1089-2044) is published biweekly by Card Player Media LLC, 6940 O’Bannon Drive, Las Vegas, NV 89117.