HR Answers Now – Employment and Labour Law 2Nd Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Harassment at Work: National and International Responses

Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 2 Conditions of Work and Employment Programme Sexual harassment at work: National and international responses Deirdre McCann INTERNATIONAL LABOUR OFFICE – GENEVA Copyright © International Labour Organization 2005 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; email: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; email: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ISBN 92-2-112680-3 (softcover) ISBN 92-2-115798-9 (.pdf version) First published 2005 Cover: DTP/Design Unit, ILO The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. The responsibility for opinions expressed in signed articles, studies and other contributions rests solely with their authors, and publication does not constitute an endorsement by the International Labour Office of the opinions expressed in them. -

Concerning Bill C-65, an Act to Amend the Canada Labour Code (Harassment and Violence)

BRIEF Concerning Bill C-65, An Act to amend the Canada Labour Code (harassment and violence) SUBMITTED BY THE CANADIAN UNION OF POSTAL WORKERS – MONTREAL LOCAL Montreal, March 5, 2018 MG/sg sepb-574 BRIEF SUBMITTED BY THE CANADIAN UNION OF POSTAL WORKERS – MONTREAL LOCAL The Canadian Union of Postal Workers – Montreal Local wishes to thank the government for introducing Bill C-65 with the aim of ending all forms of workplace harassment and violence. In support of this bill, we have submitted this brief to highlight the problem of harassment and intimidation on shop floors, the protections provided in our collective agreement and our recommendations for improving the bill. 1. The Metro-Montreal Local The Montreal Local represents over 6,735 members in 61 facilities. We have a diverse membership: 2,164 members from group 1, including postal clerks (PO4) and dispatchers (PO5). Most of these are at the Léo Blanchette Sorting Plant. The others work in corporate outlets or other facilities such as post offices where the mail is prepared for letter carrier routes. We also represent 2,592 employees from group 2: letter carriers (PO-LC) and drivers (MSC). Our membership also includes 153 tradespeople who work as technicians and mechanics. In addition, we have 303 rural and suburban mail carriers (RSMCs) and 1,523 temporary employees working in all job classes. 2. Intimidation and harassment Intimidation and harassment, particularly psychological harassment, are major concerns for the Montreal Local, since they are rooted in Canada Post’s corporate culture. The Montreal Local files an average of 2,360 grievances per year, 33% of them in response to disciplinary measures such as firings or various forms of intimidation, harassment or discrimination. -

Promoting the Labour Force Participation of Older Canadians

PROMOTING THE LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION OF OLDER CANADIANS PROMISING INITIATIVES May 2018 FEDERAL/PROVINCIAL/TERRITORIAL MINISTERS RESPONSIBLE FOR SENIORS PROMOTING THE LABOUR FORCE PARTICIPATION OF OLDER CANADIANS This publication is available for download at canada.ca/publicentre-ESDC. It is also available upon request in multiple formats (large print, Braille, MP3, audio CD, e-text CD, DAISY, or Accessible PDF), by contacting 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). By teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105. © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018 For information regarding reproduction rights: [email protected]. PDF Cat. No.: Em8-47/2018E-PDF ISBN/ISSN: 978-0-660-26216-1 ESDC Cat. No.: SSD-202-04-18E Participating Governments: Government of Alberta Government of British Columbia Government of Manitoba Government of New Brunswick Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Government of Northwest Territories Government of Nova Scotia Government of Nunavut Government of Ontario Government of Prince Edward Island Government of Saskatchewan Government of Yukon Government of Canada Acknowledgements The Labour Force Participation Working Group of the Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors would like to thank the Economic Analysis Division, Economic Policy Directorate at Employment and Social Development Canada for leading the development of this report. Quebec contributes to the FPT Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Quebec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Quebec. i Promoting the Labour Force Participation of Older Canadians TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... -

Changes to Canadian Employment & Labour Law: 2020 Year in Review

Changes to Canadian employment & labour law: 2020 year in review dentons.com • 1 Authors Henry Chang – Partner, Toronto Eleni Kassaris – Partner, Vancouver April Kosten – Partner, Calgary Mary Picard – Partner, Toronto Andy Pushalik – Partner, Toronto Catherine Coulter – Counsel, Ottawa Jeff Bastien – Senior Associate, Vancouver Roxana Jangi – Senior Associate, Calgary Jonathan Mor – Senior Associate, Toronto Claire Brown – Associate, Toronto Allison Buchanan – Associate, Toronto Stefanie Chimienti – Associate, Toronto Kyle Isherwood – Associate, Toronto Sarah Sobieraj – Associate, Calgary Larysa Workewych – Associate, Toronto The authors would like to thank Emily Kroboth and Henry Machum, articling students, for their assistance in connection with this toolkit. Disclaimer: We have developed this Toolkit to help our Canadian clients with some of the recent employment and labour changes. Please note that the information provided in this Toolkit does not constitute legal or professional advice or a legal opinion. If you have any questions, please reach out to one of the members of the Dentons Canada Labour and Employment Law group. 2 • dentons.com Articles COVID-19 — Current status Key case law developments and developments for Canadian employers 06 24 Provincial workplace mask Wrongful dismissal litigation — time to requirements from coast to coast tighten up termination language 06 26 The latest on provincial lockdowns Employment contracts — court clarifies when employment contracts are enforceable 06 Workplace screening requirements 27 from coast to coast Restrictive covenants — the return of blue pencil severance? 07 The latest developments on Canada’s travel Things we are keeping an eye on for 2021 restrictions and self-quarantine requirements 32 Working remotely - the next phase 11 CEWS update 35 Will there be a COVID-19 bump in notice cases? Key labour & employment legislative developments 37 14 Beware the COVID-19 class action.. -

What to Do If You Are Sexually Harassed

WHAT TO DO IF YOU ARE SEXUALLY HARASSED Prepared by: Canadian Resource Centre for Victims of Crime March 2018 What is sexual harassment? Sexual harassment is any conduct, comment, gesture, or contact of a sexual nature that is likely to cause offence or humiliation to any employee; or that might, on reasonable grounds, be perceived by that employee as placing a condition of a sexual nature on employment or on any opportunity for training or promotion. Some examples of sexual harassment are: asking for sex in exchange for a benefit or a favour repeatedly asking for dates, and not taking “no” for an answer demanding hugs making unnecessary physical contact, including unwanted touching using rude or insulting language or making comments toward girls and women (or boys and men) calling people sex-specific derogatory names making sex-related comments about a person’s physical characteristics or actions saying or doing something because you think a person does not conform to sex-role stereotypes posting or sharing pornography, sexual pictures or cartoons, sexually explicit graffiti, or other sexual images (including online) making sexual jokes bragging about sexual prowess bullying based on sex or gender spreading sexual rumours or gossip (including online). Prevalence According to data from Employment and Social Development Canada on harassment and sexual violence in the workplace, nearly one-third of women in Canada have experienced some form of sexual harassment at work. What can you do? 1. Talk to the harasser, make sure they know their behavior is unwanted. 2. Complain to the employer. It is their responsibility to end harassment once they’re aware of it. -

Downloadpap/ Labour%20Standards%20Act%20Consolidation.Pdf

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives | Nova Scotia August 2019 A Rising Tide to Lift All Boats Recommendations for Advances to Nova Scotia’s Labour Standards Code Rebecca Casey www.policyalternatives.ca RESEARCH ANALYSIS SOLUTIONS About the Authors Rebecca (Becky) Casey is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia and a Co- ISBN 978-1-77125-465-6 Investigator on the SSHRC Partnership Grant: “Closing the Employment Standards Enforcement This report is available free of charge at Gap: Improving Protections for Workers in www.policyalternatives.ca. Precarious Jobs”. Prof. Casey is a Research Associate of the Canadian Centre for Policy PleAse mAke A donAtIon... Alternatives-Nova Scotia. Her research uses both qualitative and quantitative research methods Help us to continue to offer our to examine long-term outcomes following publications free online. work injuries, aging with a disability, older With your support we can continue to produce workers and pathways to retirement, precarious high quality research — and make sure it gets employment, and labour standards legislation. into the hands of citizens, journalists, policy makers and progressive organizations. Visit Acknowledgments www.policyalternatives.ca or call 613-563-1341 This report has drawn guidance from the first for more information. report published by the CCPA-NS in 2012, The opinions and recommendations in this “Labour Standards Reform in Nova Scotia” by report, and any errors, are those of the authors, Kyle Buott, Larry Haiven, and Judy Haiven. The and do not necessarily reflect the views of the author has also drawn on work completed by the publishers or funders of this report. -

Labour Standards Code

Labour Standards Code CHAPTER 246 OF THE REVISED STATUTES, 1989 as amended by 1991, c. 14; 2000, c. 35; 2001, c. 6, s. 110; 2003 (2nd Sess.), c. 4, ss. 1, 2; 2003 (2nd Sess.), c. 7, ss. 4-14; 2004, c. 6, ss. 15-20; 2005, c. 38, ss. 3, 4; 2006, c. 10, ss. 1-5; 2006, c. 13, ss. 8, 9; 2006, c. 32; 2007, c. 11, s. 3; 2009, c. 18; 2010, c. 37, ss. 84-116; 2011, cc. 19, 64; 2013, c. 11; 2013, c. 35, s. 4; 2015, cc. 41, 42; 2016, c. 11; 2018, c. 1, Sch. A, s. 121; 2018, cc. 13, 36; 2020, cc. 13, 14 © 2020 Her Majesty the Queen in right of the Province of Nova Scotia Published by Authority of the Speaker of the House of Assembly Halifax This page is intentionally blank. CHAPTER 246 OF THE REVISED STATUTES, 1989 amended 1991, c. 14; 2000, c. 35; 2001, c. 6, s. 110; 2003 (2nd Sess.), c. 4, ss. 1, 2; 2003 (2nd Sess.), c. 7, ss. 4-14; 2004, c. 6, ss. 15-20; 2005, c. 38, ss. 3, 4; 2006, c. 10, ss. 1-5; 2006, c. 13, ss. 8, 9; 2006, c. 32; 2007, c. 11, s. 3; 2009, c. 18; 2010, c. 37, ss. 84-116; 2011, cc. 19, 64; 2013, c. 11; 2013, c. 35, s. 4; 2015, cc. 41, 42; 2016, c. 11; 2018, c. 1, Sch. A, s. 121; 2018, cc. 13, 36; 2020, cc. 13, 14 An Act to Provide for a Labour Standards Code Table of Contents (The table of contents is not part of the statute) Section Short title.......................................................................................................................................... -

A Softly Greying Nation: Law, Ageing and Policy in Canada

A SOFTLY GREYING NATION: LAW, AGEING AND POLICY IN CANADA Charmaine Spencer and Ann Soden* I. INTRODUCTION In the past half century, Canadian society has undergone substantial transformation, becoming more culturally heterogeneous, shifting from rural to urban economies, and witnessing large numbers of people living to be old. While in the 1960s and 1970s the country focussed on achieving social justice across broad populations, in the 1980s and 1990s, Canada began to awaken to a need for a special place for older adults within "A society for all ages", taking several first steps to achieve this goal. Today, the capacity of the country to recognize and respond appropriately to the social as well as legal needs and interests of older adults is continually being reshaped and tested. A. Legal Background Canada operates under two legal regimes: common law which is utilized in nine provinces and three territories; and a codified system of civil law, which applies within the province of Québec.1 Since 1996, aboriginal communities have also begun to take a role in the administration of justice in a manner in accordance with their culture. In Canada, the federal and provincial or territorial governments have specific areas of law and services over which they have constitutional responsibility. For example, the federal government is responsible for the Canada Health Act,2 but provinces and territories are responsible for the administration of health care coverage. Criminal law comes under federal jurisdiction, while each province is responsible for the administration of justice.3 Many areas of law affecting older adults, including family relations, marriage, property rights, adult protection, ∗ Charmaine Spencer, B.A., LL.B., LL.M., Adjunct Professor, Gerontology Research Centre, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, BC, Canada; Ann M. -

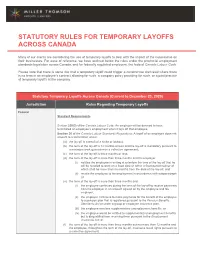

Statutory Rules for Temporary Layoffs Across Canada

STATUTORY RULES FOR TEMPORARY LAYOFFS ACROSS CANADA Many of our clients are considering the use of temporary layoffs to deal with the impact of the coronavirus on their businesses. For ease of reference, we have outlined below the rules under the provincial employment standards legislation across Canada, and for federally regulated employers, the federal Canada Labour Code. Please note that there is some risk that a temporary layoff could trigger a constructive dismissal where there is no term in an employee’s contract allowing for such, a company policy providing for such, or a past practice of temporary layoffs at the company. Statutory Temporary Layoffs Across Canada (Current to December 23, 2020) Jurisdiction Rules Regarding Temporary Layoffs Federal Standard Requirements Section 230(3) of the Canada Labour Code: An employer will be deemed to have terminated an employee’s employment when it lays off that employee. Section 30 of the Canada Labour Standards Regulations: A layoff of an employee does not amount to a termination where: (a) the lay-off is a result of a strike or lockout; (b) the term of the lay-off is 12 months or less and the lay-off is mandatory pursuant to a minimum work guarantee in a collective agreement; (c) the term of the lay-off is three months or less; (d) the term of the lay-off is more than three months and the employer (i) notifies the employee in writing at or before the time of the lay-off that he will be recalled to work on a fixed date or within a fixed period neither of which shall be more than six months -

Employment Laws in Quebec

Login Newsfeed Navigator Events Popular articles About Login Register Employment & Labor: North America Contributors QUEBEC State snapshot Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP Key considerations Which issues would you most highlight to someone new to your state? Canada > Quebec Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP Sven Poysa Because of Canada’s unique constitutional division of powers between the federal and provincial governments, most Legal updates employers in Quebec are covered by provincial legislation, although some are covered by federal legislation. The nature of an employer’s business is critical in determining whether federal or provincial legislation applies. For most employers engaged in the manufacturing, construction, retail and service sectors, provincial law applies. For employers engaged in certain inter-provincial activities – such as radio and television broadcasting, banking, shipping and rail, air and inter- QUEBEC provincial transportation generally – federal law applies. Osler Hoskin & Harcourt LLP There is no at-will employment in Canada. Rather, employment relationships are contractual. Unless there is a written contract that addresses termination, the Act Respecting Labour Standards requires that employers provide written notice to employees before terminating their employment (the required length of notice depends on the employee’s number of uninterrupted years of service). Further, the Quebec Civil Code requires that employers provide employees with reasonable notice of termination or pay in lieu of notice if the employment relationship is terminated without cause. In their application of the Quebec Civil Code, the courts are generous when prescribing the length of the termination notice that an employer must give managerial, professional or long-term employees where there is no contractual provision on the matter. -

The Disability Accommodation Gap in Canadian Workplaces: What Does It Mean for Law, Policy, and an Aging Population?

1 The Disability Accommodation Gap in Canadian Workplaces: What Does It Mean for Law, Policy, and an Aging Population? Kevin Banks, Richard P. Chaykowski & George A. Slotsve* The “accommodation gap” refers to the shortfall between those accommodations which persons with disabilities require in order to work, and those workplace accommodations which they actually receive. This paper argues that the accommodation gap raises important issues for policy- makers in Canada, given the growing participation of older workers in the labour market and the fact that the incidence of disability increases with age. Such issues include the loss of productivity, higher poverty rates, increased cost of social programs, and failure to achieve the goals of human rights legislation. Using the results of an extensive analysis of data obtained from Statistics Canada’s 2006 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey, the authors inquire into three questions: (1) Is there a workplace accommodation gap in Canada, and if there is, how big is it and whom does it affect? (2) Is it associated with age or aging, and therefore likely to be aggravated by the aging of the Canadian population? (3) Are its causes likely to elude complaint-driven enforcement of human rights law because they are systemic? In answering these questions, the study finds that a large number of Canadians (about 35%) do not receive accommodations they need to work productively, or at all. Furthermore, the results show that the older the worker and the more severe his or her disability, the greater the accommodation gap. The authors suggest that this finding supports the view that employers’ decisions on whether to provide accommodation are influenced by economic considerations, stereotypes about the link between age and disability, the fact that certain types of accommodation may conflict with workplace culture, and other factors. -

Inclusive Employment for Canadians with Disabilities

Ideas IRPP Analysis Debate S Since 1972 No. 60, August 2016 tudywww.irpp.org Inclusive Employment for Canadians with Disabilities Toward a New Policy Framework and Agenda Michael J. Prince The federal government should foster real employment opportunities for persons with disabilities by connecting employers and people with disabilities and support employers in the provision of work accommodations and job-related supports. Le gouvernement fédéral doit permettre aux personnes handicapées de participer pleinement au marché du travail, en favorisant les contacts entre elles et les employeurs, et en aidant les employeurs à leur offrir du soutien et un travail adapté. Contents Summary 1 Résumé 2 Disability and Labour Market Policy 4 Review of Disability Policies 5 Toward a New Policy Framework 14 Final Thoughts 21 Notes and References 22 About This Study 25 The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors. IRPP Study is a refereed monographic series that is published irregularly throughout the year. Each study is subject to rigorous internal and external peer review for academic soundness and policy relevance. IRPP Study replaces IRPP Choices and IRPP Policy Matters. All IRPP publications are available for download at irpp.org. If you have questions about our publications, please contact [email protected]. If you would like to subscribe to our newsletter, Thinking Ahead, please go to our Web site, at irpp.org. ISSN 1920-9436 (Online) ISSN 1920-9428 (Print) ISBN 978-0-88645-354-1-0 (Online) ISBN 978-0-88645-353-4 (Print) Summary Canadians with disabilities have consistently experienced low levels of employment, as well as barriers in the educational, economic and social spheres.