Discourse and Legitimacy in the Northern Irish Victims’ Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constituency: Newry and Armagh

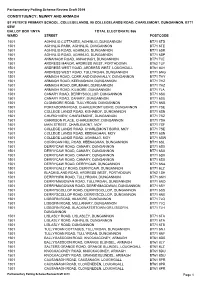

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: NEWRY AND ARMAGH ST PETER'S PRIMARY SCHOOL, COLLEGELANDS, 90 COLLEGELANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON, BT71 6SW BALLOT BOX 1/NYA TOTAL ELECTORATE 966 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1501 AGHINLIG COTTAGES, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TD 1501 AGHINLIG PARK, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6TE 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SR 1501 AGHINLIG ROAD, AGHINLIG, DUNGANNON BT71 6SP 1501 ANNAHAGH ROAD, ANNAHAGH, DUNGANNON BT71 7JE 1501 ARDRESS MANOR, ARDRESS WEST, PORTADOWN BT62 1UF 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, ARDRESS WEST, LOUGHGALL BT61 8LH 1501 ARDRESS WEST ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NG 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, CORR AND DUNAVALLY, DUNGANNON BT71 7HY 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, DRUMARN, DUNGANNON BT71 7HZ 1501 ARMAGH ROAD, KILMORE, DUNGANNON BT71 7JA 1501 CANARY ROAD, DERRYSCOLLOP, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CANARY ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SU 1501 CLONMORE ROAD, TULLYROAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6NB 1501 PORTADOWN ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, DUNGANNON BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KISHABOY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SN 1501 CHURCHVIEW, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SZ 1501 GARRISON PLACE, CHARLEMONT, DUNGANNON BT71 7SA 1501 MAIN STREET, CHARLEMONT, MOY BT71 7SF 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, CHARLEMONT BORO, MOY BT71 7SE 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, KEENAGHAN, MOY BT71 6SN 1501 COLLEGE LANDS ROAD, AGHINLIG, MOY BT71 6SW 1501 CORRIGAN HILL ROAD, KEENAGHAN, DUNGANNON BT71 6SL 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, CANARY, DUNGANNON BT71 6SX 1501 DERRYCAW ROAD, -

Identity, Authority and Myth-Making: Politically-Motivated Prisoners and the Use of Music During the Northern Irish Conflict, 1962 - 2000

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queen Mary Research Online Identity, authority and myth-making: Politically-motivated prisoners and the use of music during the Northern Irish conflict, 1962 - 2000 Claire Alexandra Green Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 I, Claire Alexandra Green, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 29/04/19 Details of collaboration and publications: ‘It’s All Over: Romantic Relationships, Endurance and Loyalty in the Songs of Northern Irish Politically-Motivated Prisoners’, Estudios Irlandeses, 14, 70-82. 2 Abstract. In this study I examine the use of music by and in relation to politically-motivated prisoners in Northern Ireland, from the mid-1960s until 2000. -

The RUC Handling of Certain Intelligence and Its Relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in Relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998

Investigation Report The RUC handling of certain intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters in relation to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998 Public Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland arising from a referral by the Chief Constable, in accordance with Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 On 4 May 2010, I received a Referral from the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) concerning a number of specific matters relating to the manner in which the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) Special Branch handled both intelligence and its relationship with Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in relation to the Omagh Bombing on 15 August 1998. The referral originated from issues identified by the House of Commons Northern Ireland Affairs Committee. 1.2 In 2013 the Chief Constable made a further Referral to my Office in connection with the findings of a report commissioned by the Omagh Support and Self Help Group (OSSHG) in support of a full Public Inquiry into the Omagh Bombing. The report identified and discussed a wide range of issues, including a reported tripartite intelligence led operation based in the Republic of Ireland involving American, British and Irish Agencies, central to which was a named agent. It suggested that intelligence from this operation was not shared prior to, or with those who subsequently investigated the Omagh Bombing. 1 1.3 On 12 September 2013 the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Theresa Villiers M.P. issued a statement explaining that there were not sufficient grounds to justify a further inquiry beyond those that had already taken place. -

Report of Sir Peter Gibson

REVIEW OF INTERCEPTED INTELLIGENCE IN RELATION TO THE OMAGH BOMBING OF 15 AUGUST 1998 [Extracts from full report] Sir Peter Gibson, the Intelligence Services Commissioner 16th January 2009 Terms of Reference by Gordon Brown, then British Prime Minister, 17 September 2008: “Review any intercepted intelligence material available to the security and intelligence agencies in relation to the Omagh bombing and how this intelligence was shared” These extracts from the full report were made available by Shaun Woodward, then Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, on 20 January 2009 16th January 2009 REVIEW OF INTERCEPTED INTELLIGENCE IN RELATION TO THE OMAGH BOMBING OF 15 AUGUST 1998 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Context 3 Background to the bombing 5 The Investigations and Actions taken after the Bombing 6 Roles and relationships 9 Sources of information relating to my review 12 Conclusions 13 Acknowledgments 16 1 of 16 Introduction 1. Following the BBC Panorama programme broadcast on 15 September, the Prime Minister invited me, as the Intelligence Services Commissioner, to “review any intercepted intelligence material available to the security and intelligence agencies in relation to the Omagh bombing and how this intelligence was shared”. 2. In preparing my Report, which I presented to the Prime Minister on 18 December 2008, I drew on a range of very sensitive and highly classified material made available to me by those agencies involved in the production of intercept intelligence. Some of this material is subject to important legal constraints on its handling and disclosure. Such material, if released more widely, would reveal information on the capabilities of our security and intelligence agencies. -

Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern

SSTTAATTEEMMEENNTT BBYY TTHHEE PPOOLLIICCEE OOMMBBUUDDSSMMAANN FFOORR NNOORRTTHHEERRNN IIRREELLAANNDD OONN HHEERR IINNVVEESSTTIIGGAATTIIOONN OOFF MMAATTTTEERRSS RREELLAATTIINNGG TTOO TTHHEE OOMMAAGGHH BBOOMMBBIINNGG OONN AAUUGGUUSSTT 1155 11999988 The persons responsible for the Omagh Bombing are the terrorists who planned and executed the atrocity. Nothing contained in this report should detract from that clear and unequivocal fact. Wednesday 12 December 2001 STATEMENT OF THE POLICE OMBUDSMAN FOR NORTHERN IRELAND IN RELATION TO THE OMAGH BOMB INVESTIGATION REPORT 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Under the provisions of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 (the Police Act), Section 55(6)(b), the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland (the Police Ombudsman) may, without a complaint, formally investigate a matter in accordance with Section 56 of the Act if it is desirable in the public interest. 1.2 A Report has been presented to the Secretary of State, the Northern Ireland Policing Board and the Chief Constable of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) under Regulation 20 of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (Complaints etc.) Regulations 2000. The public interest relates to material issues preceding and following the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998. 1.3 This Statement in relation to the Report on the Omagh Bomb is published under Section 62 of the Police (Northern Ireland) Act 1998 2. THE OMAGH BOMB 2.1 On Saturday 15 August 1998 at approximately 3.05 p.m. a terrorist bomb (the Omagh Bomb) exploded in the small county town of Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. Three telephone calls were made, the first of which was at 2.29 p.m. warning that a bomb was going to detonate in the town. -

Northern Ireland) Bill Which Is Due to Be Debated on Second Reading in the House of Commons on Wednesday 13 December 2006

RESEARCH PAPER 06/63 The Justice and 7 DECEMBER 2006 Security (Northern Ireland) Bill Bill 10 of 2006-07 This paper discusses the Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Bill which is due to be debated on second reading in the House of Commons on Wednesday 13 December 2006. A key part of the normalisation programme in Northern Ireland, following the paramilitary ceasefires and subsequent improvements in the security situation, is the expiry by July 2007 of counter-terrorist legislation specific to Northern Ireland, currently set out in Part 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000. Part 7 includes provisions currently enabling non-jury “Diplock courts” to try “scheduled offences”. The Justice and Security (Northern Ireland) Bill contains measures designed to re-introduce a presumption in favour of jury trial for offences triable on indictment, subject to a fall-back arrangement for a small number of exceptional cases for which the Director of Public Prosecutions will be able to issue a certificate stating that a trial is to take place without a jury. Amongst other things the Bill also seeks to reform the jury system in Northern Ireland, extend the powers of the Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission, provide additional statutory powers for the police and armed forces and create a permanent regulatory framework for the private security industry in Northern Ireland. Miriam Peck Pat Strickland Grahame Danby HOME AFFAIRS SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: 06/44 Judicial Review: A short guide to claims in the Administrative -

Dziadok Mikalai 1'St Year Student

EUROPEAN HUMANITIES UNIVERSITY Program «World Politics and economics» Dziadok Mikalai 1'st year student Essay Written assignment Course «International relations and governances» Course instructor Andrey Stiapanau Vilnius, 2016 The Troubles (Northern Ireland conflict 1969-1998) Plan Introduction 1. General outline of a conflict. 2. Approach, theory, level of analysis (providing framework). Providing the hypothesis 3. Major actors involved, definition of their priorities, preferences and interests. 4. Origins of the conflict (historical perspective), major actions timeline 5. Models of conflicts, explanations of its reasons 6. Proving the hypothesis 7. Conclusion Bibliography Introduction Northern Ireland conflict, called “the Troubles” was the most durable conflict in the Europe since WW2. Before War in Donbass (2014-present), which lead to 9,371 death up to June 3, 20161 it also can be called the bloodiest conflict, but unfortunately The Donbass War snatched from The Troubles “the victory palm” of this dreadful competition. The importance of this issue, however, is still essential and vital because of challenges Europe experience now. Both proxy war on Donbass and recent terrorist attacks had strained significantly the political atmosphere in Europe, showing that Europe is not safe anymore. In this conditions, it is necessary for us to try to assume, how far this insecurity and tensions might go and will the circumstances and the challenges of a international relations ignite the conflict in Northern Ireland again. It also makes sense for us to recognize that the Troubles was also a proxy war to a certain degree 23 Sources, used in this essay are mostly mass-media articles, human rights observers’ and international organizations reports, and surveys made by political scientists on this issue. -

The Diplock Courts in Northern Ireland: a Fair Trial?

Studie- en lnformatiecentrum Mensenrechten Netherlands Institute of Human Rights Institut Neerlandais des Droits de l'Homme The Diplock Courts in Northern Ireland: A Fair Trial? An analysis of the law, based on a study commissioned by Amnesty International by Douwe Korff SIM Special No. 3 Studie- en • e ourts 10 Mensenrechten orthem Ire a •• Netherlands Institute of Hu~an Rights lnstitut Neerlandais des Drotts de air Trial? l'Homme lnstituto Holandes de Derechos Human<lS Stichting Studie- en An analysis of the law. hased on a study commissioned lnfot matiecentrum Mensenrechten hy Amnesty International Nieuwegracht 94, 3512 LX UTRECI-IT, hy Douwe Korff The Netherlands, tel. 030 - 33 15 14 telex: 70779 SIM NL Cable Adress: SIMCABLE Bank: RABO-Bank Utrecht No. 39.45.75.555 Chairman Foundation: Professor P. van Dijk Director Institute: Mr. J.G.H. Thoolen The following analysis of the non-jury (" Diplock") couns in Northern Ireland was prepared in 1982 by Dutch lawyer, Douwe Korff, as a commissioned study for Amnesty International. ~ -' The text reproduced here has been shortened slightly (for reasons of economy). '' Amnesty International submitted the full text of the study in 19M3 to an official re view, then in progress, of the legislation and procedures governing such courts, as background to a recommendation that the organization's concerns he taken into ac count. SIM is grateful to Amnesty International for making the text available for independ ent publication. All rights for further reproduction are vested in Amnesty Interna tional. Table of contents Preface 7 Background note 9 List of references 14 Introduction 17 ' PART I The Pre-Triallnquiries and Proceedings 19 Chapter l The Legal Basis for Arrest and Detention for Questioning 20 (i) Ordinary Powers of Arrest 20 (ii) Common Law Essentials for a Valid Arrest 21 ( iii) Detention for Questioning 21 . -

Northern Irish Society in the Wake of Brexit

Northern Irish Society in the Wake of Brexit By Agnès Maillot Since the 2016 referendum, Brexit has dominated the political conversation in Northern Ireland, launching a debate on the Irish reunification and exacerbating communitarian tensions within Northern Irish society. What are the social and economic roots of these conflicts, and what is at stake for Northern Ireland’s future? “No Irish sea border”, “EU out of Ulster”, “NI Protocol makes GFA null and void”. These are some of the graffiti that have appeared on the walls of some Northern Irish communities in recent weeks. They all express Loyalist1 frustration, and sometimes anger, towards the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement reached in 2019 between the UK and the EU, which includes a specific section on Northern Ireland.2 While the message behind these phrases might seem cryptic to the outsider, it is a language that most of the Irish, and more specifically Northern Irish, can speak fluently. For the last four years, Brexit has regularly been making the news headlines and has dominated political conversations. More importantly, it has introduced a new dimension in the way in which the future of the UK province is discussed, prompting a debate on the reunification of the island and exacerbating a crisis within Unionism. Brexit has destabilised the Unionist community, whose sense of identity had already been tested over the last twenty years by the Peace process, by the 1 In Northern Ireland, the two main political families are Unionism (those bent on maintaining the Union with the2 The UK) withdrawal and Nationalis agreementm, wh wasich reached strives into Octoberachieve 2019a United and subsequentlyIreland. -

Inventory of Closed Mine Waste Facilities in Northern Ireland. Phase 1 Data Collection and Categorisation

Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment Minerals and Waste Programme Commercial Report CR/14/031N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS AND WASTE PROGRAMME COMMERCIAL REPORT CR/14/031 N Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment B Palumbo-Roe, K Linley, D Cameron, J Mankelow Contributor/editor T Johnston, MC Cowan The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data © Crown Copyright and database rights 2014. Ordnance Survey Licence No. 100021290. Keywords Mine waste Directive; Inventory; Northern Ireland. Bibliographical reference B PALUMBO-ROE, K LINLEY, D CAMERON, J MANKELOW. 2014. Inventory of closed mine waste facilities in Northern Ireland - Phase 2 Assessment. British Geological Survey Commercial Report, CR/14/031. 66pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2014. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation. -

William Kirk Died at His Home on December 20Th 1870 After Man Had Shaped the Development of South Armagh, While His a Long Illness

But in the campaign of 1859 the deep-seated opposition to A man of enormous energy, he found time to get involved as his liberal views became clear. He was accused of supporting chair of the Bible and Colportage Society of Ireland, helped measures injurious to Ireland, of renouncing liberalism, of to found the Presbyterian Orphan Society, and was a trustee subjugating his principles to personal ambition; and Kirk of the General Assembly’s College in Belfast. ‘His religion,’ the decided to stand down, whether motivated by disgust at the Rev. Steen emphasizes, ‘was not confi ned, as that of too many, to depths to which the opposition sank, or the pragmatism that a dying hour…He carried his religion into all the relationships and engagements of life.’ convinced him that he was unlikely to win. Th e citizens of Keady clearly agreed, and a public meeting ‘to take In 1865 he entered the arena as a candidate for Armagh, but he into consideration the propriety of raising in this town a memorial’ failed to win the seat, perhaps because the conservative infl uence was held as early as January 2nd 1871. A subscription list was was still uppermost, or because he had lost the support of some opened, and soon a fi tting monument arose, a fi ne Gothic of his co-religionists. His fi nal appearance on the political stage structure with a base of Newry granite and a superstructure of was in 1868, when, returning to Newry, he successfully contested rubbed Dungannon freestone. Th ere is a panel of polished pink his old seat. -

Catching Terrorists: the British System Versus the U.S

S. HRG. 109–701 CATCHING TERRORISTS: THE BRITISH SYSTEM VERSUS THE U.S. SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE A SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SPECIAL HEARING SEPTEMBER 14, 2006—WASHINGTON, DC Printed for the use of the Committee on Appropriations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 30–707 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri TOM HARKIN, Iowa MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland CONRAD BURNS, Montana HARRY REID, Nevada RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama HERB KOHL, Wisconsin JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire PATTY MURRAY, Washington ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota LARRY CRAIG, Idaho DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas RICHARD J. DURBIN, Illinois MIKE DEWINE, Ohio TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana WAYNE ALLARD, Colorado BRUCE EVANS, Staff Director TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire, Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BARBARA A.