Batman Begins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panther Auto Corner Left: the Band Marches on to Victory

PA NTHER PRIDE Volume 11, I ssue #2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Band's Victory in M aryville Page 1: Bands Victory in Maryville The marching band has had a fantastic Middle School Sports season! At the first competition in Carrollton they Middle School Football had a high music score but a low marching score and Page 2: Clubs and Activities flipped the scores in Cameron. On October 26th they Art Club had a competition in Maryville where they placed Elementary News second in their class 2A, only four points away from Blast Off Into the School Year first. The band had the third-highest music score over all the bands that performed. The band was very Stacking It Up excited to beat some very good bands for their last Books for First Grade marching competition of the year and are getting Character Assembly ready for concert season. Page 3: Current Events Florida Man Drumline this year had a good season. They Hong Kong Protests only had two competitions compared to the three that Creative Minds the whole band had. They played Blazed Blues and Lobster Walk for their performance. The drumline Photography Basics placed fourth in Carrollton and didn?t place in Kara Claypole, Mr.Dunker, and Ysee Chorot celebrate their "Song of the Sea" Cameron. second place trophy as they marched at Maryville for the "Bernard's Poem" Northwest Homecoming Parade. Page 4: Panther Auto Corner Left: The band marches on to victory. Ask Anonymous Entertainment Corbin's Destroy... Page 5: Joker Is a Marvel New Music Releases Page 6: New Video Game Releases Page 7: Horoscopes Page 8: November Menu Polo M iddle School Sports M iddle School Football Stats Board - By: M r. -

{Download PDF} Batman in Brave and the Bold : the Bronze Age

BATMAN IN BRAVE AND THE BOLD : THE BRONZE AGE OMNIBUS VOLUME 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike W. Barr | 904 pages | 07 Sep 2021 | DC Comics | 9781401292829 | English | United States Batman in Brave and the Bold : The Bronze Age Omnibus Volume 3 PDF Book The Authority. Mar 22, Joseph rated it really liked it Shelves: comics-graphic-novels. October 8, Part 3 - Look Homeward, Hero 7 pages. Philip Gipson March 23, Lee and Miller join forces to tell a new version of Dick Grayson's origin in a high-octane tale that unfolds with guest appearances by Superman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Black Canary and more! Cancel Update. Part 3 - Coffin for a Super-Hero 5 pages. December 10, Manton; Mrs. Part 1 - Mission to Chan 6 pages. Get weekly updates on new arrivals, reviews and recommended reads, links to cool places we find on the net and much more by signing up for our newsletter! Diogo marked it as to-read Jun 13, Related Searches. December 15, Mara marked it as to-read Mar 20, All rights reserved. October 16, Batman by Scott Snyder and Greg Capullo. David marked it as to-read Feb 02, November 14, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe. View: Large Edit cover. Disco of Death! Justice League International. Spectre : The Wrath of the Spectre. Mike W. The first ten or twelve issues that should've been in the JLA omnibus are coming out in a hardcover The Wedding of the Atom. The colors are vivid, the lines are sharp, and there are no noticeable errors. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

Joséphine Magnard Tim Burton's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Joséphine Magnard Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- MAGNARD Joséphine. Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion, sous la direction de Mehdi Achouche. - Lyon : Université Jean Moulin (Lyon 3), 2018. Mémoire soutenu le 18/06/2019. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document diffusé sous le contrat Creative Commons « Paternité – pas d’utilisation commerciale - pas de modification » : vous êtes libre de le reproduire, de le distribuer et de le communiquer au public à condition d’en mentionner le nom de l’auteur et de ne pas le modifier, le transformer, l’adapter ni l’utiliser à des fins commerciales. Master 2 Recherche Etudes Anglophones Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: A Fairy Tale between Tradition and Subversion A dissertation presented by Joséphine Magnard Year 2017-2018 Under the supervision of Mehdi Achouche, Senior Lecturer ABSTRACT The aim of this Master’s dissertation is to study to what extent Tim Burton plays with the codes of the fairy tale genre in his adaptation of Roald Dahl’s children’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964). To that purpose, the characteristics of the fairy tale genre will be treated with a specific focus on morality. The analysis of specific themes that are part and parcel of the genre such as childhood, family and home will show that Tim Burton’s take on the tale challenges the fairy tale codes, providing its viewers with a more Tim Burtonesque, subversive approach where things are not as definable as they might seem. -

How Superman Developed Into a Jesus Figure

HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE CRISIS ON INFINITE TEXTS: HOW SUPERMAN DEVELOPED INTO A JESUS FIGURE By ROBERT REVINGTON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Robert Revington, September 2018 MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario, Religious Studies TITLE: Crisis on Infinite Texts: How Superman Developed into a Jesus Figure AUTHOR: Robert Revington, B.A., M.A (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Travis Kroeker NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, 143 ii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies LAY ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. It argues that this connection was not integral to the character as he was originally created, but was imposed by later writers over time and mainly for cinematic adaptations. This thesis also tracks the history of how Christians and churches viewed Superman, as the film studios began to exploit marketing opportunities by comparing Superman and Jesus. This thesis uses the methodological framework of intertextuality to ground its treatment of the sources, but does not follow all of the assumptions of intertextual theorists. iii MA Thesis—Robert Revington; McMaster University, Religious Studies ABSTRACT This thesis examines the historical trajectory of how the comic book character of Superman came to be identified as a Christ figure in popular consciousness. Superman was created in 1938, but the character developed significantly from his earliest incarnations. -

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Dark Knight's War on Terrorism

The Dark Knight's War on Terrorism John Ip* I. INTRODUCTION Terrorism and counterterrorism have long been staple subjects of Hollywood films. This trend has only become more pronounced since the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the resulting increase in public concern and interest about these subjects.! In a short period of time, Hollywood action films and thrillers have come to reflect the cultural zeitgeist of the war on terrorism. 2 This essay discusses one of those films, Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight,3 as an allegorical story about post-9/11 counterterrorism. Being an allegory, the film is considerably subtler than legendary comic book creator Frank Miller's proposed story about Batman defending Gotham City from terrorist attacks by al Qaeda.4 Nevertheless, the parallels between the film's depiction of counterterrorism and the war on terrorism are unmistakable. While a blockbuster film is not the most obvious starting point for a discussion about the war on terrorism, it is nonetheless instructive to see what The Dark Knight, a piece of popular culture, has to say about law and justice in the context of post-9/11 terrorism and counterterrorism.5 Indeed, as scholars of law and popular culture such as Lawrence Friedman have argued, popular culture has something to tell us about society's norms: "In society, there are general ideas about right and wrong, about good and bad; these are templates out of which legal norms are cut, and they are also ingredients from which song- and script-writers craft their themes and plots."6 Faculty of Law, University of Auckland. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Deconstructing Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory: Race, Labor

Chryl Corbin Deconstructing the Oompa-Loompas Deconstructing Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory: Race, Labor, and the Changing Depictions of the Oompa-Loompas Chryl Corbin Mentor: Leigh Raiford, Ph.D. Department of African American Studies Abstract In his 1964 book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Roald Dahl de- picts the iconic Oompa-Loompas as A!ican Pygmy people. Yet, in 1971 Mel Stuart’s "lm Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory the Oompa- Loompas are portrayed as little people with orange skin and green hair. In Dahl’s 1973 revision of this text he depicts the Oompa-Loompas as white. Finally, in the "lm Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005) Tim Burton portrays the Oompa-Loompas as little brown skin people. #is research traces the changing depictions of the Oompa-Loompas throughout the written and "lm text of the Charlie and the Chocolate Factory narra- tive while questioning the power dynamics between Willy Wonka and the Oompa-Loompas characters. #is study mo$es beyond a traditional "lm analysis by comparing and cross analyzing the narratives !om the "lms to the original written texts and places them within their political and his- torical context. What is revealed is that the political and historical context in which these texts were produced not only a%ects the narrative but also the visual depictions of the Oompa-Loompas. !e Berkeley McNair Research Journal 47 Chryl Corbin Deconstructing the Oompa-Loompas Introduction In 1964 British author, Roald Dahl, published the !rst Charlie and the Chocolate Factory book in which the Oompa-Loompas are depicted as black Pygmy people from Africa. -

Batman Begins Free

FREE BATMAN BEGINS PDF Dennis O'Neil | 305 pages | 15 Jul 2005 | Random House USA Inc | 9780345479464 | English | New York, United States It's Time to Talk About How Goofy 'Batman Begins' Is | GQ As IMDb celebrates its 30th birthday, we have six shows to get you ready for those pivotal years of your life Get some streaming picks. Watch the video. When his parents are killed, billionaire playboy Bruce Wayne relocates to Asia, where he is mentored by Henri Ducard and Batman Begins Al Ghul in how to fight evil. When learning about the plan to wipe out evil in Gotham City by Ducard, Bruce prevents this plan from getting any further and heads back to his home. Back in his original surroundings, Bruce adopts the image of a bat to strike fear into the criminals and Batman Begins corrupt as the icon known as "Batman". But it doesn't stay quiet for long. Written by konstantinwe. I've just come back from a preview screening of Batman Batman Begins. I went in with low expectations, despite the excellence of Christopher Nolan's previous efforts. Talk about having your expectations confounded! This film grips like wet rope from the start. I won't give away any of the story; suffice to say it mixes and matches its sources freely, tossing in a dash of Frank Miller, a bit of Alan Moore and a pinch of Bob Kane to great effect. What's impressive is that despite the weight of the franchise, Nolan has managed to work so many of his trademarks into a mainstream movie. -

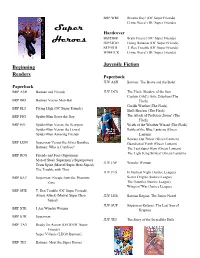

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968

THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL Reflections on Progressive Media Since 1968 CREDITS 2008 Editor: Cynthia Young 2018 Editors: Luna Olavarría Gallegos, Eric Bilach, Elizabeth Escobar and Andrew James Cover Design: Andrew James Layout Design: Luna Olavarría Gallegos Cover Photo: El Pueblo Se Levanta, Newsreel, 1971 THIRD WORLD NEWSREEL BOARD OF DIRECTORS Dorothy Thigpen (former TWN Executive Director) Sy Burgess Afua Kafi Akua Betty Yu Joel Katz (emeritus) Angel Shaw (emeritus) William Sloan (eternal) The work of Third World Newsreel is made possible in part with the support of: The National Endowment for the Arts The New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the NY State Legislature Public funds from the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council The Peace Development Fund Individual donors and committed volunteers and friends TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. TWN Fifty Years..........................................................................4 JT Takagi, 2018 2. Foreword....................................................................................7 Luna Olavarría Gallegos, 2015 3. Introduction................................................................................9 Cynthia Young, 1998 NEWSREEL 4. On Radical Newsreel................................................................12 Jonas Mekas, c. 1968 5. Newsreel: A Report..................................................................14 Leo Braudy, 1969 6. Newsreel on Newsreel.............................................................19