Soap Opera and the Broadcasting Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RFI20090644 Travel (Public Business Phone Calls Hospitality Mileage Travel (Other Costs) Facility Fees Transport)

RFI20090644 Travel (Public Business Phone Calls Hospitality Mileage Travel (Other Costs) Facility Fees Transport) Depart - Depart - Depart - Depart - Depart - Depart - Own Own Own Own Own Own mental mental mental mental mental mental Claimant Title Mark Thompson Director General 253.48 8,040.73 3,954.49 2,784.20 694.17 Mark Byford Deputy Director General 1,429.24 12.00 477.57 Timothy Davie Director, Audio & Music 5,218.99 567.20 435.95 Jana Bennett Director BBC Vision 4,017.54 135.49 34.85 483.91 Zarin Patel Chief Financial Officer 4,223.76 15.50 533.11 John Smith Chief Executive, BBC Worldwide 3.54 3,080.05 172.02 556.20 857.00 Caroline Thomson Chief Operating Officer 3,072.38 32.00 1,675.90 Adrian Van Klaveren Controller, 5 Live, Audio & Music 1,233.41 585.59 241.36 Alan Yentob Creative Director, BBC Finance 2,016.25 516.26 Andrew Parfitt Controller, R1/1Xtra/Asian Network, Audio & Music 7,044.60 1,430.90 Andy Griffee Editorial Director, Project W1, Operations 21.35 926.69 321.00 476.70 Anne Morrison Controller, Network Production, Nations & Regions 1,248.26 398.20 Balraj Samra Director of Vision Operations, BBC Vision 3,560.49 13.60 64.00 737.10 Chris Day Group Financial Controller, BBC Finance 350.64 99.54 93.00 520.53 Chris Kane Head of Corporate Real Estate, Operations Group 2.44 2,857.01 61.20 43.80 364.98 Daniel Cohen Controller, BBC Three, BBC Vision 611.03 3,148.19 150.00 15.96 338.10 189.60 Dominic Coles Chief Operating Officer, Journalism, BBC Finance 942.63 111.25 155.30 504.13 Dorothy Prior Controller Production Resource, -

BBC AR Front Part 2 Pp 8-19

Executive Committee Greg Dyke Director-General since Jana Bennett OBE Director of Mark Byford Director of World customer services and audience January 2000, having joined the BBC Television since April 2002. Service & Global News since research activities. Previously as D-G Designate in November Responsible for the BBC’s output October 2001. Responsible for all European Director for Unilever’s 1999. Previously Chairman and Chief on BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three the BBC’s international news and Food and Beverages division. Former Executive of Pearson Television from and BBC Four and for overseeing information services across all media positions include UK Marketing 1995 to 1999. Former posts include content on the UKTV joint venture including BBC World Service radio, Director then European Marketing Editor in Chief of TV-am (1983); channels and the international BBC World television and the Director with Unilever’s UK Food Director of Programmes for TVS channels BBC America and BBC international-facing online news and Beverages division and (1984), and Director of Programmes Prime. Previously General Manager sites. Previously Director of Regional Chairman of the Tea Council. (1987), Managing Director (1990) and Executive Vice President at Broadcasting. Former positions and Group Chief Executive (1991) at Discovery Communications Inc. include Head of Centre, Leeds and Carolyn Fairbairn Director of London Weekend Television. He has in the US. Former positions include Home Editor Television News. Strategy & Distribution since April also been Chairman of Channel 5; Director of Production at BBC; Head 2001. Responsible for strategic Chairman of the ITA; a director of BBC Science; Editor of Horizon, Stephen Dando Director of planning and the distribution of BBC of ITN, Channel 4 and BSkyB, and and Senior Producer on Newsnight Human Resources & Internal services. -

Ben Cogan 2015 - Freelance Casting Director

Ben Cogan 2015 - Freelance Casting Director 2016 Trendy (Feature Film) Executive Producer: Marilena Parouti Director: Louis Lagayette 2016 Son of Perdition (Short Film) Producer: Alex Carapuig Director: Matthew Harrison 2015 Just Charlie (Feature Film) Executive Producer: Karen Newman Director: Rebekah Fortune 2015 After the Fray (Short Film) Producer: Alex Carapuig Director: Matthew Harrison 2002 - 2015 Casting Director at BBC 2006 – 2015 Casualty (183 episodes and regulars) Executive Producers: Mervyn Watson, Belinda Campbell, Jonathan Phillips and Oliver Kent Series Producers: Jane Dauncey, Oliver Kent, Nikki Wilson and Erika Hossington Producers: Various Directors: Various BAFTA nominations for ‘Continuing Drama’ in 2007 (won), 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014 and 2015. 2009 Wish 143 (Short Film) Producer: Samantha Waite Director: Ian Barnes Oscar nominated. 2008 Kiss of Death (TV Movie) Executive Producer: Patrick Spence Producer: Jane Steventon Director: Paul Unwin 2007 The Real Deal Executive Producer: Will Trotter Producer: Ben Bickerton Director: Ian Barnes 2002 – 2006 Doctors (345 episodes and regulars) Executive Producers: Carson Black & Will Trotter Series Producers: Beverley Dartnall Producers: Various Directors: Various 2005 The Trouble with George Executive Producer: Mal Young & Serena Cullen Producer: Sam Hill Director: Matthew Parkhill 2000 – 2002 Casting Assistant at BBC EastEnders (225 episodes) Executive Producer: John Yorke Series Producer: Lorraine Newman Producers: Various Directors: Various Holby City (38 episodes) Executive Producer: Mal Young Series Producer: Kathleen Hutchinson Producers: Various Directors: Various In Deep (4 episodes) Executive Producer: Mal Young Producer: Steve Lanning Director: Colin Bucksey Waking the Dead (4 episodes) Executive Producer: Alexei de Keyser Producer: Joy Spink Director: Robert Knights & Gary Love EastEnders: The Return of Nick Cotton Executive Producers: Mal Young & John Yorke Producer: Beverley Dartnall Director: Chris Bernard . -

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS for the 44Th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 44th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 30th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 28th New York – March 22nd, 2017 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 30th, 2017. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 28th, 2017. The 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, “The Talk,” on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees, we are looking forward to an extraordinary celebration honoring the craft and talent that represent the best of Daytime television.” “After receiving a record number of submissions, we are thrilled by this talented and gifted list of nominees that will be honored at this year’s Daytime Emmy Awards,” said David Michaels, SVP, Daytime Emmy Awards. “I am very excited that Michael Levitt is with us as Executive Producer, and that David Parks and I will be serving as Executive Producers as well. With the added grandeur of the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, it will be a spectacular gala that celebrates everything we love about Daytime television!” The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. -

Mccready Dale Elena

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd DALE ELENA McCREADY NZCS - Director of Photography GRACE Director: John Alexander Producer: Kiaran Murray-Smith Starring: John Simm Tall Story Pictures / ITV TIN STAR (Series 3, Episodes 5 & 6) Director: Patrick Harkins Producer: Andy Morgan Starring: Tim Roth, Genevieve O’Reilly and Christina Hendricks Kudos Film and Television BELGRAVIA Director: John Alexander Producer: Colin Wratten Starring: Tamsin Greig, Philip Glenister and Alice Eve Carnival Film and Television BAGHDAD CENTRAL Director: Ben A. Williams Producer: Jonathan Curling Starring: Waleed Zuaiter, Corey Stoll and Bertie Carvel Euston Films TIN STAR (Series 2, Episodes 2, 5, 6 & 7) Directors: Gilles Bannier, Jim Loach and Chris Baugh. Producer: Liz Trubridge Starring: Tim Roth, Genevieve O’Reilly and Christina Hendricks Euston Films THE LAST KINGDOM (Series 3, Episodes 2 & 4) Director: Andy de Emmony Producers: Cáit Collins, Howard Ellis, Adam Goodman and Chrissy Skinns. Starring: Alexander Dreymon, Eliza Butterworth and Ian Hart. Carnival Film and Television THE SPLIT (Series 1) Director: Jessica Hobbs Producer: Lucy Dyke Starring: Nicola Walker, Stephen Mangan and Annabel Scholey. Sister Pictures Best TV Drama nomination – National Film Awards 2019 Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 DALE ELENA McCREADY Contd ... 2 THE TUNNEL (Series 3, Episodes 1-2) Director: Anders Engstrom Producer: Toby Welch Starring: Clémence -

Show of Success TV’S Mal Young Shares His Expertise with Students

theCaledonian News and views for the people of Glasgow Caledonian University April 2013 Glasgow Caledonian University is a registered Scottish charity, number SC021474 Show of success TV’s Mal Young shares his expertise with students In this issue... The heat is on! page three It started with a kiss page four Win a Forever 21 gift card page eight page two £25million has been invested into the Heart of the Campus project. (Facilities) The heat is on for Campus Futures Welcome A new combined heat and power Students’ Association building. The engine, system that will reduce GCU’s carbon which arrived at the beginning of April, will take If this magazine was written by footprint is on target for completion this nine weeks to fit out. “The entire thing needs to Mal Young, then it would probably start May. Work is progressing on the introduction be commissioned before it’s operational – think with a fight. Well, that’s the advice that the of a Combined Heat and Power (CHP) and of it like a test drive – to ensure it’s working the renowned TV producer gave MA TV Fiction district heating supply that will generate on-site way it should,” said Kenny. students for grabbing their viewers’ attention! electricity and heat in a single process. It will There are also plans to use the CHP as a You can read more about Mal’s hugely also supply hot water via a district heating research and teaching tool. “On completion, it successful talk on page five. network to all buildings on campus. -

Liverpool-Village-Walking-Tour-II

Liverpool Walking Tour 2019 History abounds in the Village of Liverpool. Café at 407 – 407 Tulip Street It’s 1929. Billy Frank’s Whale This latest installment of our walking Food Store at 407 Tulip St. is tours takes in houses, green spaces and offering Kellogg’s Corn Flakes for 7 cents and a pound of monuments put on them. butter for 28 cents. Cash only, please. In 1938, Fred Wagner took over the building and Stroll, imagine and enjoy, but please stay on opened Liverpool Hardware. the sidewalk! The hardware store offered tools and housewares, paint and sporting goods, garden- ing supplies, glass installations, pipe threading, and do-it-your- self machine rentals, all in the days before “big box” hardware stores. The building later housed Liverpool Stationers and other businesses. The Café at 407 and the non-profit Ophelia’s Place opened at this location in 2003. Presbyterian Church – 603 Tulip Street The brick First Presbyterian Church building is a church that salt built, dating from 1862 and dedicated on March 6, 1863. Prosperous salt manufacturers contributed heavily to its construction. The architect was Horatio Nelson White (1814- 1892), the architect of Syracuse University’s Hall of Languages, the Gridley Building in downtown Syracuse, and many others. White’s fee was $50. This style is called Second Empire, with its steeply sloping mansard roof and towers. The clock in the tower was installed in 1892, and was originally the official village clock. The Just past Grandy Park is a small neighborhood of modest Village of Liverpool paid $25 per year for use of the tower Greek Revival style houses, likely all built at about the same and maintenance of the clock. -

*^" •'•"Jsbfc''""^.' •'' '"'V^F' F'7"''^^?!CT

*^" •'•"JSBfc''""^.' •'' '"'V^f' f'7"''^^?!CT 1 AJR Information Volume XLV No. 1 January 1990 £3 (to non-members) Don't miss £4m needed to extend the Homes Back to the future P-3 AJR residential care appeal Sir Sigmund Sternberg visits Help us to meet the challenge Day Centre p. 8 he AJR together with CBF Residendal Care and Housing Association have risen to the challenge AJR Residential of the 1990s and beyond with the preparadon of a five year plan for extending and refurbishing Care Appeal - the homes, whose history now goes back more than thirty years. The plan provides for: How to T contribute . * 21 new sheltered accommodation units P-9 * 13 new rooms with toilet facilities * 102 rooms to be provided with toilet facilides * 15 rooms to offer nursing facilities The AJR through its AJR Charitable Trust has undertaken responsibility for mounnng the appeal to raise the funds for this project. Moreover, in order to permit an immediate start on the implementation of the plan the Trust has underwritten the first £500 000 of the cost. Thus work has already started on the first phase. Higher expectations Our homes offer sheltered accommodation, residendal care and full nursing care for about 250 people, a considerable number, but not enough to meet current needs. They have been shining examples of their kind, comparing favourably with others around the country. But higher standards are now expected, which means that new rooms must be built with private toilets and showers, and these facilities must be added to existing rooms. Residents are now older at the time of admission and average age in the homes has risen to 85. -

GCSE Sources and Links for the Spoken Language

GCSE Sources and Links for the Spoken Language English Language Spoken Language Task Support: Sources and Links for: Interviews and Dialogue (2014) Themes N.B. Many of these sources and links have cross-over and are applicable for use as spoken language texts for: Formal v Informal (2015) Themes. As far as possible this feature has been identified in the summary and content explanation in the relevant section below. Newspaper Sources: The Daily Telegraph ( British broadsheet newspaper) website link: www.telegraph.co.uk. This site/source has an excellent archive of relevant, accessible clips and interviews. The Guardian ( British broadsheet newspaper) website and link to their section dedicated to: Great Interviews of the 20th Century Link: http://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/series/greatinterviews This cites iconic interviews, such as: The Nixon interview is an excellent example of a formal spoken language text and can be used alongside an informal political text ( see link under ‘Political Speech’) such as Barack Obama chatting informally in a pub or his interview at home with his wife Michelle. Richard Nixon interview with David Frost Link: Youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2c4DBXFDOtg&list=PL02A5A9ACA71E35C6 Another iconic interview can be found at the link below: Denis Potter interview with Melvyn Bragg Link: Youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oAYckQbZWbU Sources/Archive for Television Interviews: The Radio Times ( Media source with archive footage of television and radio clips). There is a chronology timeline of iconic and significant television interviews dating from 1959–2011. Link: http://www.radiotimes.com/news/2011-08-16/video-the-greatest-broadcast- interviews-of-all-time Fern Britton Meet ( BBC, 2009). -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

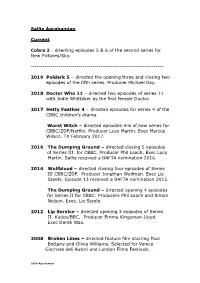

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2 - directing episodes 5 & 6 of the second series for New Pictures/Sky. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2019 Poldark 5 – directed the opening three and closing two episodes of the fifth series. Producer Michael Ray. 2018 Doctor Who 11 – directed two episodes of series 11 with Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor. 2017 Hetty Feather 4 – directed episodes for series 4 of the CBBC children’s drama. Worst Witch – directed episodes 4-6 of new series for CBBC/ZDF/Netflix. Producer Lucy Martin. Exec Marcus Wilson. TX February 2017. 2016 The Dumping Ground – directed closing 5 episodes of Series III for CBBC. Producer Phil Leach. Exec Lucy Martin. Sallie received a BAFTA nomination 2016. 2014 Wolfblood – directed closing four episodes of Series III CBBC/ZDF. Producer Jonathan Wolfman. Exec Lis Steele. Episode 13 received a BAFTA nomination 2015. The Dumping Ground – directed opening 4 episodes for Series II for CBBC. Producers Phil Leach and Simon Nelson. Exec. Lis Steele. 2012 Lip Service – directed opening 3 episodes of Series II. Kudos/BBC. Producer Emma Kingsman-Lloyd. Exec Derek Wax. 2008 Broken Lines – directed feature film starring Paul Bettany and Olivia Williams. Selected for Venice Giornate deli Autori and London Films Festivals. Sallie Aprahamian 2005 – 2009 The Bill – directed 8 episodes of the Thames/ITV series. Producers include Lachlan MacKinnon, Lis Steele and Ciara McIlvenny. 2003 Real Men – 2 x 90’ drama by Frank Deasy. Starring Ben Daniels. Producer David Snodin. Exec Frank Deasy and Barbara McKissack. BBC Scotland/BBC 2. RTS nomination. 2002 Outside the Rules – two part ‘Crime Double’ starring Daniela Nardini for BBC1/BBC Wales. -

Model Decision Notice and Advice

Reference: FS50150782 Freedom of Information Act 2000 (Section 50) Decision Notice Date: 25 March 2008 Public Authority: British Broadcasting Corporation (‘BBC’) Address: MC3 D1 Media Centre Media Village 201 Wood Lane London W12 7TQ Summary The complainant requested details of payments made by the BBC to a range of personalities, actors, journalists and broadcasters. The BBC refused to provide the information on the basis that the information was held for the purposes of journalism, art and literature. Having considered the purposes for which this information is held, the Commissioner has concluded that the requested information was not held for the dominant purposes of journalism, art and literature and therefore the request falls within the scope of the Act. Therefore the Commissioner has decided that in responding to the request the BBC failed to comply with its obligations under section 1(1). Also, in failing to provide the complainant with a refusal notice the Commissioner has decided that the BBC breached section 17(1) of the Act. However, the Commissioner has also concluded that the requested information is exempt from disclosure by virtue of section 40(2) of the Act. The Commissioner’s Role 1. The Commissioner’s duty is to decide whether a request for information made to a public authority has been dealt with in accordance with the requirements of Part 1 of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (the “Act”). In the particular circumstances of this complaint, this duty also includes making a formal decision on whether the BBC is a public authority with regard to the information requested by the complainant.