Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

How RTL Group Employees Worked up a Sweat for the 10 Years of Télévie Challenge

week 18 / 30 April 2014 PEDALLING FOR CHARITY How RTL Group employees worked up a sweat for the 10 years of Télévie Challenge Luxembourg Luxembourg United States One year anniversary RTL Group: A&E picks up FMNA of the RTL Group “Most attractive co-production, re-IPO employer in The Returned Luxembourg 2014” week 18 / 30 April 2014 PEDALLING FOR CHARITY How RTL Group employees worked up a sweat for the 10 years of Télévie Challenge Luxembourg Luxembourg United States One year anniversary RTL Group: A&E picks up FMNA of the RTL Group “Most attractive co-production, re-IPO employer in The Returned Luxembourg 2014” Cover Participants celebrating during the Télévie Challenge 2014 Publisher RTL Group 45, Bd Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg Editor, Design, Production RTL Group Corporate Communications & Marketing k before y hin ou T p r in t backstage.rtlgroup.com backstage.rtlgroup.fr backstage.rtlgroup.de QUICK VIEW Going public with teamwork – one year down the road RTL Group p.8–10 RTL Group named “Most attractive employer in Luxembourg 2014” RTL Group “Ten years of tireless p.11 dedication to a cause that is very dear to us” RTL Group A&E picks up p.4–7 The Returned FremantleMedia North America p.12 SHORT NEWS p.13 PEOPLE p.14 For the past ten years, “TEN YEARS helping to save lives has remained the clear focus of the Télévie Challenge, the OF TIRELESS Luxembourg site spinning event organised by RTL Group’s Corporate DEDICATION TO Centre in support of Télévie. To mark this milestone anniversary, the organisers A CAUSE THAT put together a special edition of the fundraising IS VERY DEAR event, which raised a record total of no less than €73,000. -

Planning Matrix for New Spiritual Home

Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of Central Oregon Planning Matrix for New Spiritual Home March 20, 2012 Edited July 1, 2012 for RFP for Architects This planning matrix is a compilation of our congregation’s dreams and needs. Workgroups comprising of about 50 members of the congregation began meeting in January 2012 to brainstorm and prioritize what we wanted in our new home. Our goal from the start has been to be inclusive, and we have incorporated suggestions from many sources: online design forums, a congregation Visioning Workshop in November, 2011, and many conversations and emails. Our intention was to dream big without limits and collect all ideas for consideration. In order to determine project feasibility, we used this matrix during our preplanning workshops in March, 2012 with our consulting architect during the Planning Grant Phase of our New Home Project. We learned then that we cannot do it all at this time. We will continue to define our space needs through research, visits to other spiritual homes, and ultimately, collaboration with our architect. Working together, we look forward to developing a master plan to phase in components as we grow. We intend for this matrix to provide a foundation when working with our architect on the programming for our future home. TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERARCHING ELEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................ 3 SUSTAINABILITY ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Sanctuary Scene Aa Publicationpublication Ofof Catskillcatskill Animalanimal Sanctuarysanctuary

SANCTUARY SCENE AA PUBLICATIONPUBLICATION OFOF CATSKILLCATSKILL ANIMALANIMAL SANCTUARYSANCTUARY Spring 2010 We Think We Can! We Know We Can! Making our dreams a reality. p. 3 PortraitsPortraits Special needs bunny and a very lucky horse. p. 6-7 CASCAS LaunchesLaunches CompassionateCompassionate CuisineCuisine Learn more and get involved. p. 8-9 Recipes p. 14 Matching Grant Update ······················································ 3 Update on our chance of a lifetime opportunity...and how you can help make it a reality. Chickens Fly Meth Lab Coop ·············································· 4 41 birds escape starvation at a Kansas City meth lab. Save the Date! ······································································ 5 A preview of this season’s exciting events. Camp Kindness registration starts now! There’s Still ―Hop‖ For the Future ······································ 6 Special bunny seeks special home. Thirty Pounds of Poop ························································ 7 Expert care and a twist of fate save a horse in distress. CAS Launches Compassionate Cuisine ························· 8-9 Meet ―The Good Chef Kev,‖ learn about our innovative cooking and gardening pro- grams, and find out how to get involved! Whatever it Takes ······························································· 10 Why CAS works. CAS Community ·································································· 11 Cheers for Volunteers! A big thank you to some dedicated humans! Welcome to the Team! Karen Wilson joins CAS staff. -

Masquerade, Crime and Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and over- worked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discern- ing readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true- crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Lee Horsley THE NOIR THRILLER Fran Mason AMERICAN GANGSTER CINEMA From Little Caesar to Pulp Fiction Linden Peach MASQUERADE, CRIME AND FICTION Criminal Deceptions Susan Rowland FROM AGATHA CHRISTIE TO RUTH RENDELL British Women Writers in Detective and Crime Fiction Adrian Schober POSSESSED CHILD NARRATIVES IN LITERATURE AND FILM Contrary States Heather Worthington THE RISE OF THE DETECTIVE IN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY POPULAR FICTION Crime Files Series Standing Order ISBN 978-0–333–71471–3 (Hardback) 978-0–333–93064–9 (Paperback) (outside North America only) You can receive future titles in this series as they are published by placing a standing order. -

Matrix in the Context of Belief Systems İnanç Sistemleri Bağlamında Matrix

Ş. Kurt, ODÜ Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi, Temmuz 2020; 10 (2), 508-527 ∙ 508 Matrix in the Context of Belief Systems İnanç Sistemleri Bağlamında Matrix ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESI Şule KURT1 Gönderim Tarihi: 17.12.2019 | Kabul Tarihi: 23.06.2020 Abstract The necessity of questioning human existence appears to be the most fundamental condition in the process of seeking meaning in the world. In the process of making sense of the outside world, man enables his own story to be formed and conveyed through an attempt to reproduce and form himself ideologically. Myth as a form reality. Myth, which is an expression of faith, affects the preservation of morality, the powerful structuring and of meaning is the fiction of social reality. Myth is not only a story told in primitive communities but a living meaning by analyzing this existence; myths and belief systems are discussed in the context of sociological methodspreading within of religious the scope rituals. of communicative In this study, knowledge action. Mythical and understanding, stories which the formed plane inof theexistence ancient and times finding are are constructud and reproduced by adapting to the power reality of mainstream cinema. cultural tools that continue to be effective today. As such, myths which reflect the power of mythological gods analysis of this existence; It has been handled with the descriptive method within the scope of the communica- tion Insystems this study, of beliefs information such as mythsand understanding and shamanism. in the example of Matrix film, the plane of existence and the nothing more than just a revelation, examining the future of humanity and describes the collective imagination According to the findings; Matrix is a science fiction movie that is so inspiring and impressive that it is elements in the Matrix scenario, he conveyed the problem of making sense of one's own existence and the universeforward-looking. -

The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 9 Issue 2 October 2005 Article 7 October 2005 He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2005) "He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Abstract Many films have used Christ figures to enrich their stories. In The Matrix trilogy, however, the Christ figure motif goes beyond superficial plot enhancements and forms the fundamental core of the three-part story. Neo's messianic growth (in self-awareness and power) and his eventual bringing of peace and salvation to humanity form the essential plot of the trilogy. Without the messianic imagery, there could still be a story about the human struggle in the Matrix, of course, but it would be a radically different story than that presented on the screen. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 Stucky: He is the One Introduction The Matrix1 was a firepower-fueled film that spin-kicked filmmaking and popular culture. -

2009 Annual Report

2009 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs PALEYDOCEVENTS ..................................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST .......................................................................................................................................19 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ..........................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ..........................................................................................21 Robert M. -

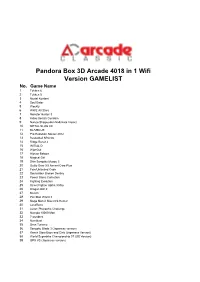

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

True Blood Returns to Hbo

TRUE BLOOD RETURNS TO HBO Miami, May 14, 2012 – HBO Latin America announced that the anticipated fifth season of the smash-hit drama series True Blood premieres in the Caribbean on June 10th, the same day as the U.S. Mixing romance, suspense, mystery and humor, the Emmy®-nominated show takes place at a time when vampires have come out of the coffin, and follows the on-and-off again romance between waitress and part-faerie Sookie Stackhouse (Anna Paquin), who can also hear people’s thoughts, and 173-year-old vampire, Bill Compton (Stephen Moyer). Season five introduces a whole new wave of otherworldly characters. Joining the cast in the 12-episode new season are Christopher Meloni (Emmy®-nominated for Law & Order: SVU) as Roman, president of the Vampire Authority; Scott Foley (Felicity) as Patrick Devins, an Iraq war veteran who comes to Bon Temps to track down his former squad-mate, Terry Bellefleur; Valentina Cervi (Jane Eyre) as Salome; Lucy Griffiths (BBC’s Robin Hood) as Nora; Kristina Anapau (Black Swan) as an enchanting faerie named Maurella; Louis Herthum (The Last Exorcism) as J.D.; Kelly Overton (The Ring Two) as Rikki, a hot new werewolf; and Dale Dickey (Winter’s Bone) as Martha. Returning cast members include Anna Paquin, Stephen Moyer, Alexander Skarsgard, Joe Manganiello, Ryan Kwanten, Rutina Wesley, Sam Trammell, Nelsan Ellis, Chris Bauer, Carrie Preston, Todd Lowe, Jim Parrack, Deborah Ann Woll, Kristin Bauer, Lauren Bowles, Janina Gavankar, Denis O’Hare and Michael McMillian. True Blood was created by Oscar® and Emmy® Award winner, Alan Ball (creator of HBO’s “Six Feet Under”); executive produced by Alan Ball and Gregg Fienberg; co-executive produced by Brian Buckner, Alexander Woo, Raelle Tucker, Mark Hudis and Angela Robinson; and co-produced by Christina Jokanovich, Marlis Pujol, and David Auge. -

A Spatial History of English Novels 1680-1770

A Spatial History of English Novels 1680-1770 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mary Jo Crone-Romanovski, M. A. English The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Roxann Wheeler, Advisor Frank Donoghue David Brewer Copyright by Mary Jo Crone-Romanovski 2010 Abstract This dissertation provides a spatial history of English novels in the period 1680- 1770. Demonstrating that space is a dynamic source of narrative, I argue that spaces are crucial to the development of new types of novels. Re-organizing novel history according to space allows me to consider eighteenth-century novel types as standalone genres rather than progressive steps toward the formation of the novel as one single, coherent genre. Thus, a spatial history of novels differs from conventional literary histories which situate major novels and authors within a linear model of chronological development and that view eighteenth-century novels as preliminary formal experiments that eventually contribute to the emergence of the nineteenth-century realist novel. Space can register in novels in a number of ways, including geographical distance, topographical location, descriptors of movement, or architectural layout. My study considers, in particular, the spaces that constitute a character‟s immediate physical environment. Each chapter examines a key space as central to a type of novel that flourished during the eighteenth century: gardens in amatory and pious novels, 1680- 1730; staircases, hallways, and closets in the domestic interior in courtship novels of the 1740s; urban homes in mid-century problem marriage novels; and sickrooms in women‟s sentimental novels of the 1750s and 1760s. -

Heuristic Futures: Reading the Digital Humanities Through Science Fiction

Heuristic Futures: Reading the Digital Humanities through Science Fiction A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences by Joseph William Dargue 2015 B.A. (Hons.), Lancaster University, 2006 M.A., Royal Holloway, University of London, 2008 Committee Chair: Laura Micciche, Ph.D. Abstract This dissertation attempts to highlight the cultural relationship between the digital humanities and science fiction as fields of inquiry both engaged in the development of humanistic perspectives in increasingly global digital contexts. Through analysis of four American science fiction novels, the work is concerned with locating the genre’s pedagogical value as a media form that helps us adapt to the digital present and orient us toward a digital future. Each novel presents a different facet of digital humanities practices and/or discourses that, I argue, effectively re-evaluate the humanities (particularly traditional literary studies and pedagogy) as a set of hybrid disciplines that leverage digital technologies and the sciences. In Pat Cadigan’s Synners (1993), I explore issues of production, consumption, and collaboration, as well as the nature of embodied subjectivity, in a reality codified by the virtual. The chapters on Richard Powers’ Galatea 2.2 (1995) and Vernor Vinge’s Rainbows End (2006) are concerned with the passing of traditional humanities practices and the evolution of the institutions they are predicated on (such as the library and the composition classroom) in the wake of the digital turn.