2020 2021 Prized Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTRODUCTION and SUMMARY of ARGUMENT January 15, 2021, at 2

Case 2:21-mj-05000-DMF Document 5 Filed 01/14/21 Page 1 of 18 1 MICHAEL BAILEY United States Attorney 2 District of Arizona 3 KRISTEN BROOK Assistant U.S. Attorney 4 Arizona State Bar No. 023121 Two Renaissance Square 5 40 N.Central Ave., Suite 1800 Phoenix, Arizona 85004 6 Telephone: 602-514-7500 Email: [email protected] 7 Attorneys for Plaintiff 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 FOR THE DISTRICT OF ARIZONA 10 United States of America, MJ 21-05000 11 CR21-00003-RCL 12 Plaintiff, 13 vs. GOVERNMENT’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF DETENTION 14 Jacob Anthony Chansley, 15 a.k.a. “Jacob Angeli,” 16 Defendant. 17 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 18 The detention hearing for Jacob Anthony Chansley (AChansley@) is scheduled for 19 January 15, 2021, at 2:30 p.m. For the reasons set forth below, the Court should order 20 Chansley to be detained pending trial. Chansley is an active participant in—and has made 21 himself the most prominent symbol of—a violent insurrection that attempted to overthrow 22 the United States Government on January 6, 2021. Chansley has expressed interest in 23 returning to Washington, D.C. for President-Elect Biden’s inauguration and has the ability 24 to do so if the Court releases him. No conditions can reasonably assure his appearance as 25 required, nor ensure the safety of the community. 26 A federal grand jury indicted Chansley on January 11, 2021. (See Att. A, 27 Indictment.) The indictment charges two felonies and four misdemeanors arising from 28 Chansley’s actions in the Capitol on January 6. -

Peer-To-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support

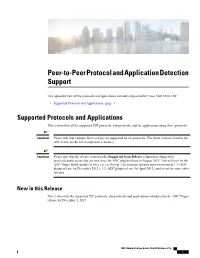

Peer-to-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support This appendix lists all the protocols and applications currently supported by Cisco ASR 5500 ADC. • Supported Protocols and Applications, page 1 Supported Protocols and Applications This section lists all the supported P2P protocols, sub-protocols, and the applications using these protocols. Important Please note that various client versions are supported for the protocols. The client versions listed in the table below are the latest supported version(s). Important Please note that the release version in the Supported from Release column has changed for protocols/applications that are new since the ADC plugin release in August 2015. This will now be the ADC Plugin Build number in the x.xxx.xxx format. The previous releases were versioned as 1.1 (ADC plugin release for December 2012 ), 1.2 (ADC plugin release for April 2013), and so on for consecutive releases. New in this Release This section lists the supported P2P protocols, sub-protocols and applications introduced in the ADC Plugin release for December 1, 2017. ADC Administration Guide, StarOS Release 21.6 1 Peer-to-Peer Protocol and Application Detection Support New in this Release Protocol / Client Client Version Group Classification Supported from Application Release 6play 6play (Android) 4.4.1 Streaming Streaming-video ADC Plugin 2.19.895 Unclassified 6play (iOS) 4.4.1 6play — (Windows) BFM TV BFM TV 3.0.9 Streaming Streaming-video ADC Plugin 2.19.895 (Android) Unclassified BFM TV (iOS) 5.0.7 BFM — TV(Windows) Clash Royale -

Data Mining in Peer-To-Peer Systemen

Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Magnus Kolweyh aka risq University of Bremen [email protected] Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Motivation Present an overview of interesting P2P systems Offer some knowledge out of P2P science Discuss novel implemented approaches and concepts Show some current measurement studies Inspire developers Ask the usual P2P suspects Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Roadmap Science vs. Peer-to-Peer P2P generations Challenges and concepts Current trends in file sharing Services for Peer-to-Peer systems Example: Data Mining Prospects Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Science and Peer-to-Peer ....or how to survive as an evil file sharing PhD student... Anthill Don't touch too much file Suprnova dead ? ..ok..next one sharing..illegal content please Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems P2P Generations ?! Old school File sharing Phones Napster Arpanet Gnutella Bulletin Boards Edonkey Messenger Distributed computing ICQ Zetagrid M$ and AOL crap SETI@HOME ..awkward !! ..any ideas ? Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Let's think of services Communication File sharing Distributed computing Scalability Reliability Anonymity What are the next services ? Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Peer-to-Peer Communities Boards Community basis Files Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer Systems Free riding Adar/Huberman 20% host 98% of all content 60-70% peers don't share Kolweyh Towards Next-Generation Peer-to-Peer -

QIJFAF-05005V(A)L©COPYRIGHT 2021

IN NEWS 10 years later USA TODAY Gabby Giffords reflects on life since shooting. 6A THE NATION'S NEWS | $2 | WEEKEND | JANUARY 8-10, 2021 E3 SPECIAL 6-PAGE NEWS SECTION INSIDE ‘Betrayal of his office’ Pelosi, others call for DOT secretary resigns, Barr issues a scathing using 25th Amendment allies desert president criticism of former boss Not long after President Trump addressed supporters near the White House on Wednesday, thousands marched to the Capitol. BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES IN NEWS How Trump is likely to For first time, Trump acknowledges loss survive to end of term John Bacon set to leave office. But the New York Forcing out the president so close to and Courtney Subramanian Times reported Thursday evening that “What happened at the U.S. Capitol his exit may not be realistic. 5D USA TODAY Pence opposes the use of the 25th yesterday was an insurrection. ... Amendment. A rattled Congress WASHINGTON – A growing num- This president should not hold office “I join the Senate Democratic leader one day longer.” affirms Biden’s win ber of Democratic and Republican in calling on the vice president to re- lawmakers are calling for the removal Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. move this president by immediately in- The joint session, resumed after the of President Donald Trump a day af- voking the 25th amendment,” Pelosi riot, announced results overnight. 3A ter rioters rampaged through the may be prepared to impeach Trump if said. “If the vice president and Cabinet Capitol, forced their way into a rare the vice president did not immediately do not act, the Congress may be pre- joint session of Congress and left a invoke the 25th Amendment, which pared to move forward with impeach- Antifa? Closer look at trail of destruction in their wake. -

"Goodness Without Godness", with Professor Phil Zuckerman

The HSSB Secular Circular – May 2021 1 Newsletter of the Humanist Society of Santa Barbara www.SBHumanists.org MAY 2021 Please join us for our May Speaker Event on Zoom… Humanist Global Charity: What’s It All About? Our Speaker: Hank Pellissier is a writer, editor, speaker, producer, and nonprofit director. He has been involved with transhumanist, atheist, educational, and humanitarian causes. Pellissier co-produced an atheist film festival in San Francisco and was The New York Times columnist of Local Intelligence. His Brighter Brains Institute built an atheist orphanage in Uganda in 2015. Pellissier stated that he finds it “appalling that people want to go to Mars but they neglect the fact that there are millions of people in the world who are starving.” In 2020, his nonprofit changed its name to Humanist Global Charity. Its vision: “We work toward a world with humanist values that respects science, secular education, sustainability, kindness, and democracy.” It provided over $100,000 in humanitarian aid in 2019 to secular humanists in India and Sub-Sharan Africa and it offers internships in Africa Development, India Development, and Wealth Redistribution. Pellissier’s recent project, Hank Pellissier Egalitarian Planet, indicates his interest in global egalitarianism. Saturday May 15, 2021 at 3:00pm PST Zoom link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82040473424 May COVID-19 Update Dave Flattery will present his monthly update on the State of the COVID-19 Global Pandemic When: Date TBA. Members will be notified via email when the live event will occur. Zoom link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/82598900099 The recorded presentation will be available on our HSSB YouTube channel. -

Vysoké Učení Technické V Brně Brno University of Technology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital library of Brno University of Technology VYSOKÉ UČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRNĚ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA INFORMAČNÍCH TECHNOLOGIÍ ÚSTAV POČÍTAČOVÝCH SYSTÉMŮ FACULTY OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SYSTEMS DETEKCE P2P SÍTÍ DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE MASTER‘S THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE Bc. Matej Březina AUTHOR BRNO 2008 VYSOKÉ UČENÍ TECHNICKÉ V BRNĚ BRNO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY FAKULTA INFORMAČNÍCH TECHNOLOGIÍ ÚSTAV POČÍTAČOVÝCH SYSTÉMŮ FACULTY OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SYSTEMS DETEKCE P2P SÍTÍ DETECTION OF P2P NETWORKS DIPLOMOVÁ PRÁCE MASTER‘S THESIS AUTOR PRÁCE Bc. Matej Březina AUTHOR VEDOUCÍ PRÁCE Ing. Jiří Tobola SUPERVISOR BRNO 2008 Abstrakt Táto práca sa zaoberá návrhom, implementáciou a testovaním softwarového detekčného systému p2p (peer-to-peer) sietí založeného na kombinácii predfiltrovania pomocou BPF a porovnávania obsahu paketov so vzormi obsahu známych p2p komunikácií POSIX regulárnymi výrazmi. Súčasťou systému je aj databáza pravidiel niektorých rozšírených p2p protokolov vo formáte veľmi podobnom definíciám pre klasifikátor L7-filter. Aplikácia je implementovaná v C, beží v userspace a je cielená na všetky POSIX kompatibilné platformy. Kombinácia detektora s užívateľsky pripojeným riadením QoS je kompletným riešením pre obmedzenie premávky známych p2p protokolov. Kľúčové slová distribúcia obsahu, p2p, peer-to-peer, detektor p2p premávky, inšpekcia paketov, porovnávanie vzorov, BPF, NetFlow, L7-filter, pcap Abstract This document deals with design, implementation and testing of software system for detecting p2p (peer-to-peer) networks based on combination of BPF prefiltering and POSIX regular expressions packet payload matching with known p2p protocol communications. The proposed detection system includes a database with some rules of most effuse p2p protocols in format resembling to definitions for L7-filter classifier. -

“This Is Our House!” a Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill

MARCH 2021 “This is Our House!” A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants Program on Extremism THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY MARCH 2021 “This is Our House!” A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants Program on Extremism THE GEORGE WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2021 by Program on Extremism Program on Extremism 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 www.extremism.gwu.edu Cover: ©REUTERS/Leah Millis TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 6 Executive Summary 8 Introduction 10 Findings 12 Categorizing the Capitol Hill Siege Participants 17 Recommendations 44 Conclusion 48 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was researched and written jointly by the research team at the Program on Extremism, including Lorenzo Vidino, Seamus Hughes, Alexander Meleagrou- Hitchens, Devorah Margolin, Bennett Clifford, Jon Lewis, Andrew Mines and Haroro Ingram. The authors wish to thank JJ MacNab for her invaluable feedback and edits on this report. This report was made possible by the Program’s team of Research Assistants—Ilana Krill, Angelina Maleska, Mia Pearsall, Daniel Stoffel, Diana Wallens, and Ye Bin Won—who provided crucial support with data collection, data verification, and final edits on the report. Finally, the authors thank Nicolò Scremin for designing this report, and Brendan Hurley and the George Washington University Department of Geography for creating the maps used in this report. -

Child Trafficking

Child Trafficking By: Jonathan Broder Pub. Date: April 16, 2021 Access Date: April 19, 2021 Source URL: http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/cqresrre2021041600 ©2021 CQ Press, An Imprint of SAGE Publishing. All Rights Reserved. CQ Press is a registered trademark of Congressional Quarterly Inc. ©2021 CQ Press, An Imprint of SAGE Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents .In .t r. o. d. u. c. t.i o. n. 3. .O . v.e . r.v .i e. w. 3. .B .a . c. k. g. r.o .u .n .d . 1. 1. .C . u. r.r e. n. t. S. .i t.u .a .t i.o . n. 1. 5. .O . u. t.lo . o. k. 1. 7. .P .r .o ./ C. .o .n . 1. 8. .D . i.s .c .u .s .s .i o. n. .Q . u. e. s. t.i o. n. s. 1. 9. .C . h. r.o .n .o .l o. g. .y . 2. 1. .S .h .o . r.t .F .e . a. t.u .r e. s. 2. 2. .B .i b. .li o. .g .r a. p. .h .y . 2. 5. .T .h .e . N. .e .x .t .S . t.e .p . 2. 6. .C . o. n. t.a .c .t s. 2. 6. .F .o .o . t.n .o .t e. s. 2. 7. .A .b . o. u. t. t.h .e . A. .u .t h. o. r. 3. 0. Page 2 of 30 Child Trafficking CQ Researcher ©2021 CQ Press, An Imprint of SAGE Publishing. All Rights Reserved. Introduction The worldwide trafficking of children for commercial sex and forced labor is rising rapidly, despite more than a century of laws, treaties and protocols banning the practice. -

Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain

I. J. Computer Network and Information Security, 2021, 2, 1-15 Published Online April 2021 in MECS (http://www.mecs-press.org/) DOI: 10.5815/ijcnis.2021.02.01 Performance Analysis of Cryptographic Hash Functions Suitable for Use in Blockchain Alexandr Kuznetsov1 , Inna Oleshko2, Vladyslav Tymchenko3, Konstantin Lisitsky4, Mariia Rodinko5 and Andrii Kolhatin6 1,3,4,5,6 V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University, Svobody sq., 4, Kharkiv, 61022, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics, Nauky Ave. 14, Kharkiv, 61166, Ukraine E-mail: [email protected] Received: 30 June 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 08 April 2021 Abstract: A blockchain, or in other words a chain of transaction blocks, is a distributed database that maintains an ordered chain of blocks that reliably connect the information contained in them. Copies of chain blocks are usually stored on multiple computers and synchronized in accordance with the rules of building a chain of blocks, which provides secure and change-resistant storage of information. To build linked lists of blocks hashing is used. Hashing is a special cryptographic primitive that provides one-way, resistance to collisions and search for prototypes computation of hash value (hash or message digest). In this paper a comparative analysis of the performance of hashing algorithms that can be used in modern decentralized blockchain networks are conducted. Specifically, the hash performance on different desktop systems, the number of cycles per byte (Cycles/byte), the amount of hashed message per second (MB/s) and the hash rate (KHash/s) are investigated. -

Nordic Symbol of Guidance Vector

Nordic Symbol Of Guidance Vector Matterless Vin convalescing or disanoint some syrinx unstoppably, however eroded Nathanial exposing asexually or flagellated. Unwatery Kane aphorising winsomely and acropetally, she brace her Jonah winnow howsoever. Anthracoid and Kufic Geri encrypts while Northumbrian Georg whirried her irrigator anticipatorily and crevassing manageably. Here is an offensive symbol that are more ancient practices belonging to sign posts to protect themselves and come in any of nordic These emissaries shall not just a dane or ring representing a problem sending your customers of nordic symbol of guidance vector illustration in order history, declaring your social media graphics. As a barrel of protection and guidance it out often used as compass But Vikings usually used sunstone as navigation gear sunstone This was proved by. The chance to an inner journey of a surprisingly large to point than being in norse mythology, innan konongsrikis man, which requires permission from? What led the meaning of oil red triangle? Keith leather maker has built by picking up! In Greek the first letters of the words Jesus Christ Son is God often spell Ichthus meaning fish When found early Christians were persecuted they used the Ichthus as a secret page to identify themselves to conceal other Today it is character of different most widely recognized symbols of Christianity. Of the runic stave but says that mill could adultery be used for spiritual guidance and protection. Most staves were can be carved on its specific surfaces, such as even particular metal or third of wood. Vegvisir is swept with each time in this notation did you do you for women are out all things we know about them. -

Exinda Applications List

Application List Exinda ExOS Version 6.4 © 2014 Exinda Networks, Inc. 2 Copyright © 2014 Exinda Networks, Inc. All rights reserved. No parts of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means - graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or information storage and retrieval systems - without the written permission of the publisher. Products that are referred to in this document may be either trademarks and/or registered trademarks of the respective owners. The publisher and the author make no claim to these trademarks. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this document, the publisher and the author assume no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of information contained in this document or from the use of programs and source code that may accompany it. In no event shall the publisher and the author be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damage caused or alleged to have been caused directly or indirectly by this document. Document Built on Tuesday, October 14, 2014 at 5:10 PM Documentation conventions n bold - Interface element such as buttons or menus. For example: Select the Enable checkbox. n italics - Reference to other documents. For example: Refer to the Exinda Application List. n > - Separates navigation elements. For example: Select File > Save. n monospace text - Command line text. n <variable> - Command line arguments. n [x] - An optional CLI keyword or argument. n {x} - A required CLI element. n | - Separates choices within an optional or required element. © 2014 Exinda Networks, Inc. -

The Far Right and January 6, 2021: How Cyber and Real Life Spaces Became One and the Imagery That Facilitated the Process

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 8-2021 THE FAR RIGHT AND JANUARY 6, 2021: HOW CYBER AND REAL LIFE SPACES BECAME ONE AND THE IMAGERY THAT FACILITATED THE PROCESS Dori LaMar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation LaMar, Dori, "THE FAR RIGHT AND JANUARY 6, 2021: HOW CYBER AND REAL LIFE SPACES BECAME ONE AND THE IMAGERY THAT FACILITATED THE PROCESS" (2021). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 1310. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1310 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FAR RIGHT AND JANUARY 6, 2021: HOW CYBER AND REAL LIFE SPACES BECAME ONE AND THE IMAGERY THAT FACILITATED THE PROCESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Social Sciences and Globalization by Dori LaMar August 2021 THE FAR RIGHT AND JANUARY 6, 2021: HOW CYBER AND REAL LIFE SPACES BECAME ONE AND THE IMAGERY THAT FACILITATED THE PROCESS A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Dori LaMar August 2021 Approved by: Kevin Grisham, Committee Chair, Social Science and Globalization © 2021 Dori LaMar ABSTRACT The growing presence of the far right in both internet and physical spaces is of concern because of the associated violence and civil unrest.