Analysis of Mass Bird Mortality in October, 1954

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. Paris Agreements23 OCTOBER 1954I. Four Power Conference – Paris, 23 October 1954

THE ORGANISATION OF COLLECTIVE SELF-DEFENCE 35 5. Paris Agreements23 OCTOBER 1954I. Four Power Conference – Paris, 23 October 1954 The United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the French Republic and the Federal Republic of Germany agree as follows: 1. Protocol on the Termination of the Occupation Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany 2. Annexes I to V Attached to the Protocol on the Termination of the Occupation Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany 3. Letters Ten letters were exchanged following the signing of the agreements: letters from the Chancellor to the three Ministers for Foreign Affairs, letters from the three High Commissioners to the Chancellor and letters from the three Ministers for Foreign Affairs to the Chancellor. These letters deal with specific points in the Bonn Conventions which were deleted therefrom by mutual consent, the Parties concerned having agreed to deal with them by an exchange of letters. In the absence of the text of the Conventions their contents would be virtually unintelligible, so they have been omitted from the present work. 4. Convention on the Presence of Foreign Forces in the Federal Republic of Germany 5. Three-Power Declaration on Berlin II. Documents Signed by Five Parties 1. Declaration Inviting Italy and the Federal Republic of Germany to Accede to the Brussels Treaty – Paris, 23 October 1954 III. Nine-Power Conference 1. Protocol Modifying and Completing the Brussels Treaty – Paris, 23 October 1954 2. Protocol No. 11 on Forces of Western European Union – Paris, 23 October 1954 3. Protocol No. -

Cradle of Airpower Education

Cradle of Airpower Education Maxwell Air Force Base Centennial April 1918 – April 2018 A Short History of The Air University, Maxwell AFB, and the 42nd Air Base Wing Air University Directorate of History March 2019 1 2 Cradle of Airpower Education A Short History of The Air University, Maxwell AFB, and 42nd Air Base Wing THE INTELLECTUAL AND LEADERSHIP- DEVELOPMENT CENTER OF THE US AIR FORCE Air University Directorate of History Table of Contents Origins and Early Development 3 The Air Corps Tactical School Period 3 Maxwell Field during World War II 4 Early Years of Air University 6 Air University during the Vietnam War 7 Air University after the Vietnam War 7 Air University in the Post-Cold War Era 8 Chronology of Key Events 11 Air University Commanders and Presidents 16 Maxwell Post/Base Commanders 17 Lineage and Honors: Air University 20 Lineage and Honors: 42nd Bombardment Wing 21 “Be the intellectual and leadership-development center of the Air Force Develop leaders, enrich minds, advance airpower, build relationships, and inspire service.” 3 Origins and Early Development The history of Maxwell Air Force Base began with Orville and Wilbur Wright, who, following their 1903 historic flight, decided in early 1910 to open a flying school to teach people how to fly and to promote the sale of their airplane. After looking at locations in Florida, Wilbur came to Montgomery, Alabama in February 1910 and decided to open the nation’s first civilian flying school on an old cotton plantation near Montgomery that subsequently become Maxwell Air Force Base (AFB). -

Director's Corner

Summer Issue 2021 Director’s Corner Pg. 1 & 2 TSF Update Pg. 2 Gift Shop News Pg. 3 Hollywood & Ft. Rucker MUSEUM GIFT SHOP HOURS WEBSITE Pg. 4 & 5 Foundation Update Pg. 6 MONDAY - FRIDAY 9 - 4 MONDAY - FRIDAY Summer 2021 Pg. 7 SATURDAY 9 - 3 9 - 4 Membership Pg. 7 CLOSED FEDERAL HOLIDAYS. SATURDAY OPEN MEMORIAL DAY, 9 - 2:45 INDEPENDENCE DAY AND VETERANS DAY WWW.ARMYAVIATIONMUSEUM.ORG GIFT SHOP - CLICK ‘SHOP’ DIRECTOR’S CORNER Bob Mitchell, Museum Director reetings once again from the Army Aviation Museum! As we enter the summer season and the country opens back up, we are gearing up for a Army Aviation Museum Foundation G busy season. I noticed an unusually high volume of traffic on the interstate over the P.O. Box 620610 weekend and realized folks are eager to travel, visit family and trying to put 2020 in the Fort Rucker, AL 36362 rear view mirror. All this is good news for museums as well as others that count on attendance. This past Sunday, June 6th marked the anniversary of the D-Day landing, but it was also the 79th anniversary of the birth of Organic Army Aviation. General Order number 98 was signed giving the Ground Forces their own aircraft, pilots and mechanics as part of their Tables of Organization and Equipment (TO&E). Each Artillery unit would be authorized two aircraft, two pilots and one mechanic. These crews would travel and live with the unit in the field and provide reconnaissance, target spotting, medical evacuation and a host of other services. -

United States Air Force Judge Advocate General's Corps

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL’S CORPS BACKGROUND Over 1,300 active duty military attorneys, called judge advocates (JAGs), have discovered that service as a commissioned officer in the Air Force Judge Advocate General's Corps (JAG Corps) has much to offer. Our legal practice is challenging and offers early opportunities to litigate in a variety of forums. In addition, practicing law in the JAG Corps allows attorneys to engage in public service within an institution highly respected by the American public. Our JAGs make a fulfilling, valuable and lasting contribution to the United States of America, while maintaining a high quality of life. The JAG Corps provides the United States Air Force with all types of legal support. As an officer in the JAG Corps and a practicing attorney your responsibilities will focus on all legal aspects of military operations including: criminal law, legal assistance, civil and administrative law, labor and employment law, international and operational law, space and cyberspace law, contract and fiscal law, medical law, and environmental law. The JAG Corps offers a wide range of opportunities--whether serving as prosecutor, defense counsel, or special victims’ counsel at a court-martial, advising a commander on an international law issue, or helping an Airman with a personal legal matter. For some, travel opportunities, the possibility of living and practicing law in a foreign country, and the simple prospect of engaging in a unique legal field carry special attraction. For others, quality of life is of significant importance. Military service provides an extended family, emphasizes teamwork and team building, and offers a well- developed support network. -

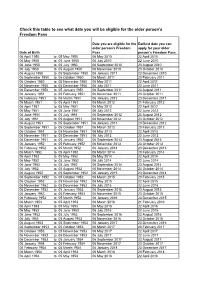

Copy of Age Eligibility from 6 April 10

Check this table to see what date you will be eligible for the older person's Freedom Pass Date you are eligible for the Earliest date you can older person's Freedom apply for your older Date of Birth Pass person's Freedom Pass 06 April 1950 to 05 May 1950 06 May 2010 22 April 2010 06 May 1950 to 05 June 1950 06 July 2010 22 June 2010 06 June 1950 to 05 July 1950 06 September 2010 23 August 2010 06 July 1950 to 05 August 1950 06 November 2010 23 October 2010 06 August 1950 to 05 September 1950 06 January 2011 23 December 2010 06 September 1950 to 05 October 1950 06 March 2011 20 February 2011 06 October 1950 to 05 November 1950 06 May 2011 22 April 2011 06 November 1950 to 05 December 1950 06 July 2011 22 June 2011 06 December 1950 to 05 January 1951 06 September 2011 23 August 2011 06 January 1951 to 05 February 1951 06 November 2011 23 October 2011 06 February 1951 to 05 March 1951 06 January 2012 23 December 2011 06 March 1951 to 05 April 1951 06 March 2012 21 February 2012 06 April 1951 to 05 May 1951 06 May 2012 22 April 2012 06 May 1951 to 05 June 1951 06 July 2012 22 June 2012 06 June 1951 to 05 July 1951 06 September 2012 23 August 2012 06 July 1951 to 05 August 1951 06 November 2012 23 October 2012 06 August 1951 to 05 September 1951 06 January 2013 23 December 2012 06 September 1951 to 05 October 1951 06 March 2013 20 February 2013 06 October 1951 to 05 November 1951 06 May 2013 22 April 2013 06 November 1951 to 05 December 1951 06 July 2013 22 June 2013 06 December 1951 to 05 January 1952 06 September 2013 23 August 2013 06 -

Aircraft of Today. Aerospace Education I

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 287 SE 014 551 AUTHOR Sayler, D. S. TITLE Aircraft of Today. Aerospace EducationI. INSTITUTION Air Univ.,, Maxwell AFB, Ala. JuniorReserve Office Training Corps. SPONS AGENCY Department of Defense, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 179p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Aerospace Education; *Aerospace Technology; Instruction; National Defense; *PhysicalSciences; *Resource Materials; Supplementary Textbooks; *Textbooks ABSTRACT This textbook gives a brief idea aboutthe modern aircraft used in defense and forcommercial purposes. Aerospace technology in its present form has developedalong certain basic principles of aerodynamic forces. Differentparts in an airplane have different functions to balance theaircraft in air, provide a thrust, and control the general mechanisms.Profusely illustrated descriptions provide a picture of whatkinds of aircraft are used for cargo, passenger travel, bombing, and supersonicflights. Propulsion principles and descriptions of differentkinds of engines are quite helpful. At the end of each chapter,new terminology is listed. The book is not available on the market andis to be used only in the Air Force ROTC program. (PS) SC AEROSPACE EDUCATION I U S DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO OUCH) EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN 'IONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EOU CATION POSITION OR POLICY AIR FORCE JUNIOR ROTC MR,UNIVERS17/14AXWELL MR FORCEBASE, ALABAMA Aerospace Education I Aircraft of Today D. S. Sayler Academic Publications Division 3825th Support Group (Academic) AIR FORCE JUNIOR ROTC AIR UNIVERSITY MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE, ALABAMA 2 1971 Thispublication has been reviewed and approvedby competent personnel of the preparing command in accordance with current directiveson doctrine, policy, essentiality, propriety, and quality. -

Floods of October 1954 in the Chicago Area, Illinois and Indiana

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OP THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLOODS OF OCTOBER 1954 IN THE CHICAGO AREA ILLINOIS AND INDIANA By Warren S. Daniels and Malcolm D. Hale Prepared in cooperation with the STATES OF ILLINOIS AND INDIANA Open-file report Washington, D. C., 1955 PREFACE This preliminary report on the floods of October 1954 in the Chicago area of Illinois and Indiana was prepared by the Water Resources Division, C. G. Paulsen, chief, under the general direction of J. V. B. Wells, chief, Surface Water Branch. Basic records of discharge in the area covered by this report were collected in cooperation with the Illinois De partment of Public Works and Buildings, Division of Waterways; the Indiana Flood Control and Water Resources Commission; and the Indiana Department of Conservation, Division of Water Re sources. The records of discharge were collected and computed under the direction of J. H. Morgan, district engineer, Champaign, 111.; and D. M. Corbett, district engineer, Indi anapolis, Ind. The data were computed and te^t prepared by the authors in the district offices in Illinois and Indiana. The report was assembled by the staff of the Technical Stand ards Section in Washington, D. C., Tate Dalrymple, chief. li CONTENTS Page Introduction............................................. 1 General description of floods............................ 1 Location.............................................. 1 Little Calumet River basin........................... -

MAXWELL WILLIAM CALVIN MAXWELL Born: Nov

Namesakes 1 1 2 3 4 MAXWELL WILLIAM CALVIN MAXWELL Born: Nov. 9, 1892, Natchez, Ala. Death in Manila Died: Aug. 12, 1920, Manila, Philippines Occupation: US military officer On April 6, 1917, the US entered the Great Soon, Maxwell was generating sorties from a Service: ROTC; US Air Service War. It was a matter of instant significance new, air-only section of Stotsenburg: Clark Field. Era: World War I/post-WW I for William C. Maxwell, an obscure student The young aviator was flying the Dayton-Wright Years of Service: 1917-20 at the University of Alabama. His response DH-4 biplane, a US version of Geoffrey de Grade: Second Lieutenant would, over time, make his name famous Havilland's famous two-seat, single-engine Combat: None throughout the Air Force. British bomber. College: University of Alabama Maxwell was born into humble circum- On Aug. 12, 1920, disaster struck. Maxwell stances in tiny Natchez, Ala., one of seven was on a routine flight when he experienced children. Their father, John R. Maxwell, and engine trouble. The 400-hp Liberty engine mother, Jennie, moved the family to Atmore, was usually reliable. On this day, it was not. MAXWELL AIR FORCE BASE where he grew up. Maxwell attempted an emergency landing in Maxwell, 24 when war came, was older a nearby sugarcane field. On approach, losing State: Alabama than the usual undergraduate. He possibly altitude, he saw that a group of children was Nearest City: Montgomery began college late because he lacked the playing in a clearing directly in his path. -

Lodging Guest Book Air Forces Inns | 2

UNIVERSITY INN MAXWELL-GUNTER GUEST SERVICES DIRECTORY “On the campus of world leadership” Air Force Inns | 1 Table of Content General Information Welcome Letter ......................................................................................................................................................PG 4 University Inn Mission-Vision Statement .......................................................................................................PG 6 Air Force Inn Promise & Forgot a Travel Item ...............................................................................................PG 6 Lodging Information Lodging Responsibility ........................................................................................................................................ PG 8 Occupant Responsibility ..................................................................................................................................... PG 8 Fire and Safety ...................................................................................................................................................... PG 9 Energy Conservation ........................................................................................................................................... PG 9 Energy Conservation Tips .................................................................................................................................PG 10 Alcohol Consumption/ Gatherings / Parties ............................................................................................... -

October 1954

OCTOBER 1954 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CUHMENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE Albuquerque, N. Mex. No. 10 208 U. S, Courthouse UUA S. Broadway OCTOBER 1954 Atlanta 5. Ga, Memphis 3, Twin. 50 Seventh St. ML Boston 9, Mass. Miami 32, Fla. U. S. Post Office and 36 NE. First St, Courthouse Bldg. MfameapoHs2tMmn. Buffalo 3, N. Y. 607MarqoetteAre. 117 Ellicott Sti Charleston 4, S. C, Area 2, Sergeant Jasper Bldg. PAGE New York 17. N.Y. 110E.4Sth! THE BUSINESS SITUATION 1 Cheyenne, Wyo, 307 Federal Office Bldg. Philadelphia 7. Pa. National Income and Corporate Profits, Chicago 6, 111. 226 W, Jackson Blvd. Phomix.Ari,, Cincinnati 2, Ohio 137 N. Second Are. 422 U. S. Post Office and Courthouse 107 Sixth St, SPECIAL ARTICLES Cleveland 14, Ohio 1100 Chester Ave« 520 SW. Morrison St. Foreign Grants and Credits Dallas 2, Tea. U. S. Government, Fiscal 1954, 7 Reno,Ner. 1114 Commerce St. 1479 V«lh Are. Private and Public Debt in 1953, 13 Denver 2, Colo, Richmond 20, Va. 142 New Custom House WON.LomhardySt. Detroit 26, Mich, St. Louis 1, Mo. 230 W, Fort St. 1114 Market St, El Paso, Tex. Salt Lake Cit7l, Utah Chamber of Commerce 222 SW. Temple St. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS . S-l to S-40 Bid*. Houston 2, Tex. San Francisco U, Calif. Statistical Index . Inside back cover 430 Lamar Ave. 555 Battery St. Jacksonville 1, Fla, Sarannab. Ga. 311 W, Monroe St. 125-29 BullSt. Kansas City 6, Mo, Seattle 4, Wash. 911 Walnut St. -

Dondi E. Costin, Ph.D. Major General United States Air Force

DONDI E. COSTIN, PH.D. MAJOR GENERAL UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Hometown Currently Serving In Wilmington NC Washington DC EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, Leadership, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Louisville, Kentucky) Dissertation: Essential Leadership Competencies for U.S. Air Force Wing Chaplains Doctor of Ministry, Church Growth, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (Louisville, Kentucky) Dissertation: Applying the Purpose-Driven Church Paradigm to a Multi-Congregational Air Force Chapel Setting Master of Divinity, Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (Fort Worth, Texas) Master of Strategic Studies, Air University (Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama) Master of Military Operational Art and Science, Air University (Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama) Master of Arts in Religion, Liberty Baptist Theological Seminary (Lynchburg, Virginia) Master of Arts, Counseling, Liberty University (Lynchburg, Virginia) Bachelor of Science, Operations Research, The United States Air Force Academy (Colorado Springs, Colorado) SENIOR EXECUTIVE EXPERIENCE Chief of Chaplains, United States Air Force, The Pentagon 2015 – Pres .. Senior advisor to 4-star Air Force Chief of Staff leading 664,000 Airmen and their family members. .. Oversees 4,500 employees, $1.5B in facilities, and $70M budget serving 100+ campuses worldwide. .. Directs 9 major geographically-separated divisions to advance organizational mission across the globe. .. Generated $10M annual budget increase to boost educational funding for Service Members and families. .. Serves as Chaplain Corps College senior official, overseeing college mission, vision, curriculum and budget. .. Wrote Air Force Chaplain Corps Strategic Plan, linking Chaplain Corps’ spiritual care and resilience strategy to the United States Air Force’s Strategic Master Plan. .. Launched global FaithWorks campaign to connect resilience with academic research on religion and health. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS October 1956 in Transportation, the Rise That Has Occurred in Payrolls Quently

OCTOBER 1956 U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE OFFICE OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE FIELD SERVICE No. 10 Albuquerque, N. Mex. Memphis 3, Term. 321 Post Office Bldg. 22 North Front St. OCTOBER 1956 Atlanta 23, Ga. Miami 32, Fla. 50 Seventh St. NE. 300 NE. First Ave. Boston 9, Mass. Minneapolis 2, Minn. U.S. Post Office and 2d Ave. South and Courthouse Bldg. 3d St. Buffalo 3, N. Y. New Orleans 12, La. 117 Ellicott St. 333 St. Charles Ave, Charleston 4, S. C. New York 17, N. Y. Area 2, 110 E. 45th St. PAGE Sergeant Jasper Bldg. THE BUSINESS SITUATION.. 1 Cheyenne, Wyo. Philadelphia 7, Pa. 307 Federal Office Bldg. 1015 Chestnut St. Recent Changes in Manufacturing and Trade. 2 National Income and Corporate Profits 7 Chicago 6, III. Phoenix, Ariz. 226 W. Jackson Blvd. 137 N. Second Ave. Cincinnati 2, Ohio Pittsburgh 22, Pa. * * * 442 U. S. Post Office 107 Sixth St. and Courthouse Portland 4, Oreg. SPECIAL ARTICLES Cleveland 14, Ohio 520 SW. Morrison St. 1100 Chester Ave. Financing Corporate Expansion in 1956 11 Dallas 2, Tex. Reno, Nev. Major Shift by Areas in Foreign Aid in Fiscal 1114 Commerce St. 1479 Wells Ave. 1956 17 Denver 2, Colo. Richmond 19, Va. 142 New Customhouse 1103 East Main St. * * * Detroit 26, Mich. St. Louis 1, Mo. 1114 Market St. MONTHLY BUSINESS STATISTICS S-l to S-40 438 Federal Bldg. Houston 2, Tex. Salt Lake City 1. Utah Statistical Index Inside back cover 430 Lamar Ave. 222 SW. Temple St.