J.Krishnamurti's Notion of Freedom from the Known: an Observation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindful Meditation Guide and Journal-Mindfulness Exercises Copy

mindful meditation guide and journal Date / Time So far today, have you brought kind awareness to your: Thoughts? Heart? Body? None of the Above First o, congratulations on your decision to enhance your personal growth through mindfulness! This is something you are doing for yourself and your well-being so make a commitment to schedule formal times to practice these exercises just as you would other important appointments. It is easy to lose enthusiasm and dedication to a new practice when obstacles arise and daily tasks begin to get in the way so it is important to gure out what is working and what is not so that you can adjust your practice as needed. Before beginning mindfulness practices, it is important to understand the concept of mindfulness and what the practice of mindfulness can mean for you in your eorts towards personal growth. Mindfulness practice often embodies eight attitudes. These attitudes contribute to the growth and ourishing of your mind, heart and body so it is important to under- stand and recognize the dening points of the eight attitudes of mindfulness listed on the next page. MindfulnessExercises.com mindful meditation guide and journal 1. Learner’s mind – Seeing things as a visitor in a foreign land, everything is new and curious. 2. Nonjudgmental – Becoming impartial, without any labels of right or wrong or good or bad. Simply allowing things to be. 3. Acknowledgment – Recognizing things as they are. 4. Settled – Being comfortable in the moment and content where you are. 5. Composed – Being equanimous and in control with compassion and insight. -

Introduction to Mindfulness & Meditation Session 4 Handout

Introduction to Mindfulness & Meditation Session 4 Handout Sometimes people think that the point of meditation is to stop thinking — to have a silent mind. This does happen occasionally, but it is not necessarily the point of meditation. Thoughts are an important part of life. Mindfulness practice is not a struggle against thoughts, but overcoming our preoccupation with them. Mindfulness is not thinking about things; it is observation of our life in all its aspects. In those moments when thinking predominates, mindfulness is the clear and silent awareness that we are thinking. Thoughts can come and go as they wish, and the meditator does not need to become involved with them. In meditation, when thoughts are subtle and in the background, or when random thoughts pull you away from awareness of the present, it is enough to resume mindfulness of breathing. However, when your preoccupation with thoughts is stronger than your ability to easily let go of them, then direct your mindfulness to being clearly aware that thinking is occurring. Sometimes thinking can be strong and compulsive even while we are aware of it. When this happens, notice how such thinking is affecting your body, physically and energetically. Let your mindfulness feel the sensations of tightness, pressure, or whatever you discover. When you feel the physical sensation of thinking, you are bringing attention to the present moment rather than the story line of the thoughts. When a particular theme keeps reappearing in our thinking, it is likely being triggered by a strong emotion. If the associated emotion isn’t recognized, the concern will keep reappearing. -

A Concise Biography of Jiddu Krishnamurti: an Indian Philosopher of Contemporary Society

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 5, Issue 11, November 2018, PP 38-42 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0511005 www.arcjournals.org A Concise Biography of Jiddu krishnamurti: An Indian Philosopher of Contemporary Society Paulo Nuno Martins* Interuniversity Center for History of Science and Technology, New University of Lisbon, Campus of Caparica, Building VII, Floor 2, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal *Corresponding Author: Paulo Nuno Martins, Interuniversity Center for History of Science and Technology, New University of Lisbon, Campus of Caparica, Building VII, Floor 2, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal Abstract : Jiddu Krishnamurti was a spiritual Indian philosopher of contemporary society. In this essay, I will describe the most important milestones of his life, particularly the main works (talks, books, videos) performed by him in the field of meditation, relationships and education. Keywords: Spiritual Indian Philosopher, Initiation (Mystical Union),Meditation, Relationships, Education. 1. INTRODUCTION Jiddu Krishnamurti was born on 12th May 1895, in the town of Mandanapalle, in Andhra Pradesh from a family of Brahmins who spoke the Telegu. He was the eighth son of Jiddu Narianiah (father) and Jiddu Sanjeevamma (mother) who had eleven children. His mother died when he was ten years old, while his father worked in the Revenue Department of the British administration and was a member of Theosophical Society [1]. In 1907, after retired from his job, Narianiah became a clerk in the Theosophical Society, in Adyar. During this time, Krishnamurti and his brother Nitya were tutored by the theosophists Charles Lead beater and Annie Besant. -

Choiceless Awareness

- Bangalore 1948 - 1st Public Talk 2nd Public Talk 3rd Public Talk 4th Public Talk 5th Public Talk 6th Public Talk 7th Public Talk - New Delhi 1948 - 3rd Public Talk Talk On Radio BANGALORE 1ST PUBLIC TALK 4TH JULY, 1948 Instead of making a speech, I am going to answer as many questions as possible, and before doing so, I would like to point out something with regard to answering questions. One can ask any question; but to have a right answer, the question must also be right. If it is a serious question put by a serious person, by an earnest person who is seeking out the solution of a very difficult problem, then, obviously, there will be an answer befitting that question. But what generally happens is that lots of questions are sent in, sometimes very absurd ones, and then there is a demand that all those questions be answered. It seems to me such a waste of time to ask superficial questions and expect very serious answers. I have several questions here, and I am going to try to answer them from what I think is the most serious point of view; and, if I may suggest, as this is a small audience, perhaps you will interrupt me if the answer is not very clear, so that you and I can discuss the question. Question: What can the average decent man do to put an end to our communal problem? Krishnamurti: Obviously the sense of separatism is spreading throughout the world. Each successive war is creating more separatism, more nationalism, more sovereign governments, and so on. -

SESSION 2 DEFINITION of MEDIATION & OBSERVATION MANAGEMENT the Real Meaning of Meditation What Is Meditation? How Does It Wo

SESSION 2 DEFINITION OF MEDIATION & OBSERVATION MANAGEMENT The Real Meaning of Meditation What is meditation? How does it work? Can meditation help you achieve genuine peace and happiness in today’s hectic, often chaotic world? 1 : To engage in contemplation or reflection 2 : To engage in mental exercise (as concentration on one's breathing or repetition of a mantra) for the purpose of reaching a heightened level of spiritual awareness 1 : To focus one's thoughts on : reflect on or ponder over 2 : To plan or project in the mind : INTEND, PURPOSE The act or process of spending time in quiet thought: the act or process of meditating An expression of a person's thoughts on something Full Definition of MEDITATION 1 A discourse intended to express its author's reflections or to guide others in contemplation 2 The act or process of meditating See meditation defined for English-language learners See meditation defined for kids 2 Meditation is a word that has come to be used loosely and inaccurately in the modern world. That is why there is so much confusion about how to practice it. Some people use the word meditate when they mean thinking or contemplating; others use it to refer to daydreaming or fantasizing. However, meditation (dhyana) is not any of these. Meditation is a precise technique for resting the mind and attaining a state of consciousness that is totally different from the normal waking state. It is the means for fathoming all the levels of ourselves and finally experiencing the center of consciousness within. Meditation is not a part of any religion; it is a science, which means that the process of meditation follows a particular order, has definite principles, and produces results that can be verified. -

A School That Values Connectedness: an Educational Project in the Midst of a Beautiful Natural Environment

A School That Values Connectedness: An Educational Project in the Midst of a Beautiful Natural Environment Hiroshi Mochizuki Master Student, Master's Program in the Graduate School Division of Education, International Christian University “Many people are highly aware of other people’s happiness and try to share in it. On the other hand, many human beings pay no attention to others’ misery.”1 When thinking about Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), it is probably important to understand how sharing contributes to consciousness of the connectedness between oneself and others, as expressed in the quote above. In this paper, I would like to discuss the educational practices of Rishi Valley Education Centre, which is located in the suburbs of India’s Andhra Pradesh State about 140 kilometers northeast of the city of Bangalore in the state of Karnataka. The institution promotes connectedness between students and teachers through discussion and interaction, and fosters connectedness with nature by enabling students and teachers to experience the blessings of the natural environment. The Natural Environment of Rishi Valley Education Centre The Rishi Valley Education Centre was established in 1926 in Andhra Pradesh State in southern India in order to give concrete form to the educational ideas of the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986). Educational institutions established by Krishnamurti exist both within and outside India.2 Among these institutions, Rishi Valley Education Centre was the first to be established. The spacious 250-acre campus includes the Rishi Valley School, the boarding school that all of the approximately 350 students in grades 4-12 (ages 8-17) attend; the Rishi Valley Rural Education Centre, which provides free educational opportunities for residents of nearby rural villages; a Rural Health Centre that plays the role of a hospital and includes facilities for tuberculosis treatment and for eye care; and a Krishnamurti Study Centre which houses books about Krishnamurti and which visitors can use as a library. -

Bulletin 2015

bulletin Krishnamurti Foundation of America No. 89 2015 The Krishnamurti Foundation of America P.O. Box 1560 Ojai, CA 93024 U.S.A. Ph: 805-646-2726 Fx: 805-646-6674 Email: [email protected] Web: www.kfa.org The Foundation gratefully accepts donations to support its many publications, which include books, CDs, DVDs, and downloadable web-based files. © Krishnamurti Foundation of America 2015 All rights reserved. Krishnamurti with students at Oak Grove School, 1979 Photo by Michael Mendizza KFA Bulletin #89 2015 Unconditioning & Education Dear Friends, The material in this Bulletin is a chapter from a new book titled Unconditioning and Education. It contains one of the discussions Krishnamurti had with staff, trustees and parents in 1975, on founding the Oak Grove School in Ojai. It has been a rarity in history that such an important religious and philosophical teacher be directly involved in creating schools to bring about a deep psychological change. The topics of the discussions are unusual for a school setting—bringing about a new human being, freedom versus authority, religion and a new culture, psychological change, the art of listening and how to invite trust. Changing human consciousness is the mission of the school. This implies a responsibility of the whole of humanity beyond those directly involved in the school. The vision of these teachings is truly a paradigm shift. In these discussions Krishnamurti challenges the participants to look beyond the question of “how to”. He challenges them to drop methods and systems when it comes to creating an atmosphere where students and staff can flower together and come upon something sacred. -

Commentaries on Living Series 2

Commentaries On Living Series 2 COMMENTARIES ON LIVING SERIES II CHAPTER CHAPTER 1 2 ’CONDITIONING’ HE WAS VERY concerned with helping humanity, with doing good works, and was active in various social-welfare organizations. He said he had literally never taken a long holiday, and that since his graduation from college he had worked constantly for the betterment of man. Of course he wasn’t taking any money for the work he was doing. His work had always been very important to him, and he was greatly attached to what he did. He had become a first-class social worker, and he loved it. But he had heard something in one of the talks about the various kinds of escape which condition the mind, and he wanted to talk things over. ”Do you think being a social worker is conditioning? Does it only bring about further conflict?” Let us find out what we mean by conditioning. When are we aware that we are conditioned? Are we ever aware of it? Are you aware that you are conditioned, or are you only aware of conflict, of struggle at various levels of your being? Surely, we are aware, not of our conditioning, but only of conflict, of pain and pleasure. ”What do you mean by conflict?” Every kind of conflict: the conflict between nations, between various social groups, between individuals, and the conflict within oneself. Is not conflict inevitable as long as there is no integration between the actor and his action, between challenge and response? Conflict is our problem, is it not? Not any one particular conflict, but all conflict: the struggle between ideas, beliefs, ideologies, between the opposites. -

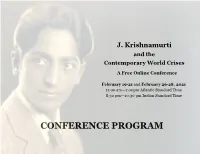

CONFERENCE PROGRAM About the Conference

J. Krishnamurti and the Contemporary World Crises A Free Online Conference February 19-21 and February 26-28, 2021 11:00 am—1:00pm Atlantic Standard Time 8:30 pm—10:30 pm Indian Standard Time CONFERENCE PROGRAM About the Conference The world-renowned Indian philosopher and educator J. Krishnamurti has offered some of the most novel insights into the nature of human consciousness and our conflicts. In this conference, Canadian and Indian scholars, educators, and alumni of Krishnamurti schools, will engage in a cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary dialogue aimed at understanding contemporary world crises (including the COVID-19 pandemic) through the lens of Krishnamurti’s philosophical and educational ideas. The diverse and multi-national community of thinkers gathered for this conference represent disci- plines ranging from law to physics to education. They will draw on their own insight and personal ex- periences to deepen our understanding of J. Krishnamurti’s ideas in modern contexts. The keynote addresses will be delivered by Dr. Meenakshi Thapan, Dr. Ravi Ravindra, and Dr. Hillary Rodrigues, who combined, have decades of experience engaging with Krishnamurti’s insights into human con- sciousness, conflict, dialogue, and the art of awareness. Over six two-hour sessions, panellists and attendees will explore such questions as: • What are the primary crises that face modern society? How have these been highlighted or exacer- bated by the COVID-19 pandemic? • How might the ideas of J. Krishnamurti help us identify the root of our crises and conflicts and to identify possible responses? • Considering the crises that face humanity, what should the education of children and youth entail? • How have students educated in Krishnamurti schools been prepared for life— its conflicts, strug- gles, and demands? Conference Organising Committee Dr. -

The Beauty of the Mountain · Memories of J. Krishnamurti

The Beauty of the Mountain · Memories of J. Krishnamurti The BeautyMemories of theof J. KrishnamurtiMountain Friedrich Grohe Including the following quotations from Krishnamurti: ‘Shall I talk about your teachings?’ ‘Brockwood Today and in the Future’ ‘The Intent of the Schools’ ‘The setting sun had transformed everything’ ‘Relationship with nature’ ‘Indifference and understanding’ ‘An idea put together by thought’ ‘Education for the very young’ ‘An extraordinary space in the mind’ ‘It is our earth, not yours or mine’ ‘The Core of K’s Teaching’ ‘The Study Centres’ ‘Krishnamurti’s Notebook – A Book Review’ © 1991 and 2014 Friedrich Grohe Seventh Edition Photographs were taken by Friedrich Grohe unless stated otherwise www.fgrohephotos.com Design: Brandt-Zeichen · Rheinbach · Germany Printed by Pragati Offset Pvt Ltd, India All Krishnamurti extracts are © Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd, except for those from On Living and Dying, which are © Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd and Krishnamurti Foundation of America. ISBN 978-1-937902-25-4 KRISHNAMURTI FOUNDATIONS Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd Brockwood Park, Bramdean, Hampshire SO24 0LQ, England Tel: [44] (0)1962 771 525 [email protected] www.kfoundation.org Krishnamurti Foundation of America P.O. Box 1560, Ojai, California 93024, USA Tel: [1] (805) 646 2726 [email protected] www.kfa.org Krishnamurti Foundation India Vasanta Vihar, 124 Greenways Road, RA Puram, Chennai 600 028, India Tel: [91] 44 2 493 7803 [email protected] www.kfionline.org Fundación Krishnamurti Latinoamericana Calle Ernest Solvay 10, 08260 Suria (Barcelona), Spain Tel: [34] 938 695 042 [email protected] www.fkla.org Additional Websites www.jkrishnamurti.org www.kinfonet.org ontents C Acknowledgements . -

Stress Reduction: Mindfulness for Personal and Professional Wellbeing

Stress Reduction: Mindfulness for Personal and Professional Wellbeing COURSE INSTRUCTOR: Steven Rosenzweig, MD, Clinical Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine, Drexel University College of Medicine. [email protected] This is a for-credit, Professionalism Elective designed specifically for medical students to learn proven methods for lowering stress and reducing stress-related anxiety, depressed mood, physical tension, and for increasing well-being and concentration. (See below for fuller course description.) The course is offered in the fall and again in the winter. See the Professionalism Course calendar for dates and times this year. Pre-registration is required. Mindfulness meditation for stress reduction is taught at numerous of medical schools. This course teaches various forms of mindfulness meditation, a very accessible practice that calms the mind and relaxes the body. It is based on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, an 8-week program that is offered at hundreds of medical centers nationally and around the world. Some comments from past DUCoM participants: "I have learned how to reduce stress in my everyday life. I have gained a sense of relaxation that I found difficult to achieve previously." "It really helps me sleep." "I found this class very relaxing and a breath of fresh air compared to all the other craziness going on in medical school. It was an hour I actually anticipated just to get away from everything else and focus on me...Mindfulness has been very helpful at times when I feel stressed and overwhelmed with school." "I use [mindfulness] to relax when I feel as if I am stressed and unable to focus. -

J. Krishnamurti‟S Concepts of Freedom, Meditation, Love and Truth - a Philosophical Study

J. Krishnamurti‟s concepts of freedom, meditation, love and truth - a philosophical study A thesis submitted to Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth , Pune For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) In Philosophy Under the Board of Moral and Social Sciences Studies Submitted by SushamaKarve Under the guidance of Dr. VaijayantiBelsare July 2015 1 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the present thesis titled as “J. Krishnamurti‟s concepts of freedom, meditation, love and truth-a philosophical study”, is a result of an original research done by Sushama A. Karveand it is completed under my supervision for the fulfillment of the degree of Ph.D. at the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. Such material as has been obtained from outside sources has been duly acknowledged. Place: Date: Dr. Vaijayanti Belsare Research Guide 2 DECLARATON I hereby affirm that the research work titled as J. Krishnamurti‟s concepts of freedom, meditation, love and truth-a philosophical study, is an original work carried out by me. It does not contain any work for which a degree or diploma has been awarded by any other university. Place: Date: Sushama Karve Research Student 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I take this opportunity to thank Dr. Deepak Tilak, the vice chancellor of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, and Dr. Umesh Keskar, registrar of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth,for granting me the opportunity to explore my topic at the university. All the teachers, the library and the administration staff extended an invaluable help for this study. I thank them sincerely. The non-teaching staff also helped me frequently. I thank them all. Prof. Vijay Karekar introduced me to J.Krishnamurti‟s teachings and encouraged and supported me all through this research.