NATO and Russia: Post- Georgia Threat Perceptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Relationship Between Democratisation and the Invigoration of Civil Society in Hungary, Poland and Romania

The Relationship between Democratisation and the Invigoration of Civil Society in Hungary, Poland and Romania Mehmet Umut Korkut Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of DPhil Central European University, Department of Political Science May 2003 Supervisor: PhD Committee: András Bozóki, CEU Aurel Braun, University of Toronto Reinald Döbel, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster Zsolt Enyedi, CEU Anneci÷ime ve BabacÕ÷Õma, Beni ben yapan de÷erleri, Beni özel kÕlan sevgiyi, Beni baúarÕOÕ eden deste÷i verdikleri için . 1 Abstract: This is an explanation on how and why the invigoration of civil society is slow in Hungary, Poland and Romania during their democratic consolidation period. To that end, I will examine civil society invigoration by assessing the effect of interest organisations on policy-making at the governmental level, and the internal democracy of civil society organisations. The key claim is that despite previously diverging communist structures in Hungary, Poland and Romania, there is a convergence among these three countries in the aftermath of their transition to democracy as related to the invigoration of civil society. This claim rests on two empirical observations and one theoretical argument: (1) elitism is widely embedded in political and civil spheres; (2) patron-client forms of relationship between the state and the civil society organisations weaken the institutionalisation of policy-making. As a result, there is a gap between the general and specific aspects of institutionalisation of democracy at the levels of both the political system and civil society. The theoretical argument is that the country-specific historical legacies from the communist period have only a secondary impact on the invigoration of civil society in the period of democratic consolidation. -

Studia Politica 42015

www.ssoar.info The politics of international relations: building bridges and the quest for relevance Braun, Aurel Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Braun, A. (2015). The politics of international relations: building bridges and the quest for relevance. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 15(4), 557-566. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-51674-8 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de The Politics of International Relations Building Bridges and the Quest for Relevance 1 AUREL BRAUN The 21 st Century sadly is proving to be a volatile and violent one where the hopes of the immediate years of the post-Cold War era have proven to be ephemeral. International Relations, (IR) at first blush, appears to be ideally positioned as a discipline to help us understand or even cope with the extreme dissonance of the international system. A discreet academic field for a century now, but in fact one of the oldest approaches, IR seems to brim with promise to offer explanation, identify causality and enable cogent prediction. After all, in an era where we emphasize interdisciplinary studies and across-the-board approaches IR appears to be a compelling intellectual ecosystem. -

Uncertain Times Jeopardize Enlargement

Strong Headwinds Uncertain Times Jeopardize Enlargement By Pál Dunay PER CONCORDIAM ILLUSTRATION 18 per Concordiam stablished 70 years ago with the signa- The FRG’s accession 10 years after the end Visitors walk past a tures of 12 original members, NATO of World War II in Europe, in May 1955, had remaining section E of the Berlin Wall now has 29 members, meaning more than half multiple consequences. It meant: in 2018. The end of are accession countries. Enlargement by accession • The FRG’s democratic record had been the Cold War and occurred over seven separate occasions, and on recognized. the unification of one occasion the geographic area increased with- • The country could be integrated militarily, Europe entailed out increasing the number of member states when which signaled its subordination and a clear the unification of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) became requirement not to act outside the Alliance. Germany. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS part of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in • The FRG’s membership in NATO created an October 1990. incentive for the establishment of the Warsaw The conditions surrounding the enlarge- Pact, which followed West German membership ments — the first in 1952 (Greece and Turkey) by five days in 1955 and led to the integration and the most recent in 2017 (Montenegro) — have of the GDR into the eastern bloc. This signaled varied significantly. The first three enlargements the completion of the East-West division, at occurred during the Cold War and are regarded least as far as security was concerned. as strategic. They contributed to the consolida- tion of the post-World War II European order The third enlargement — Spain in 1982 — meant and helped determine its territorial boundaries. -

Jack L. Snyder Robert and Renée Belfer

Jack L. Snyder Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Relations Saltzman Institute of War and Peace Studies, Department of Political Science Columbia University December 4, 2019 1327 International Affairs Building 420 W. 118 St. New York, NY 10027 work tel: 212-854-8290 e-mail: [email protected] fax: 212-864-1686 Education Ph.D., Columbia University, political science (international relations), 1981. Certificate of the Russian Institute, Columbia University, 1978. B.A., Harvard University, government, 1973. Teaching Columbia University, Political Science Department, full professor, 1991; tenured associate professor, 1988; assistant professor, 1982. Graduate and undergraduate courses on international politics, nationalism, and human rights. Publications: Books Power and Progress: International Politics in Transition (Routledge, 2012), a selection of my articles on anarchy, democratization, and empire published between 1990 and 2010, with a new introduction, conclusion, and chapter on “Democratization and Civil War.” Co-authored with Edward Mansfield, Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005). Lepgold Prize for the best book on international relations published in 2005. Foreword Book of the Year Gold Award in Political Science for 2005. Choice Magazine Outstanding Academic Title, 2006. From Voting to Violence: Democratization and Nationalist Conflict. W. W. Norton, 2000. Indonesian edition, 2003. Chinese edition, Shanghai Press, 2017. Myths of Empire: Domestic Politics and International Ambition. Cornell University Press, 1991. Korean edition, 1996. Chinese edition, 2007. The Ideology of the Offensive: Military Decision Making and the Disasters of 1914 Cornell University Press, 1984. “Active citation” web version of ch. 7, 2014, at https://qdr.syr.edu/. 2 Edited books Co-editor with Stephen Hopgood and Leslie Vinjamuri, Human Rights Futures (Cambridge University Press, 2017); author of chapter, “Empowering Rights,” and co- author of introduction and conclusion. -

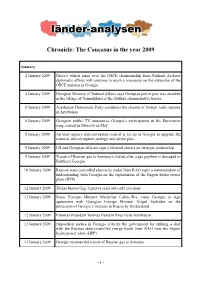

Chronicle: the Caucasus in the Year 2009

Chronicle: The Caucasus in the year 2009 January 2 January 2009 Greece, which takes over the OSCE chairmanship from Finland, declares diplomatic efforts will continue to reach a consensus on the extension of the OSCE mission in Georgia 4 January 2009 Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs says Georgian police post was attacked in the village of Ganmukhuri at the Abkhaz administrative border 6 January 2009 Azerbaijan Democratic Party condemns the closure of foreign radio stations in Azerbaijan 6 January 2009 Georgian public TV announces Georgia’s participation in the Eurovision song contest in Moscow in May 8 January 2009 An inter-agency anti-corruption council is set up in Georgia to upgrade the national anti-corruption strategy and action plan 9 January 2009 US and Georgian officials sign a bilateral charter on strategic partnership 9 January 2009 Transit of Russian gas to Armenia is halted after a gas pipeline is damaged in Southern Georgia 10 January 2009 Russian state-controlled electricity trader Inter RAO signs a memorandum of understanding with Georgia on the exploitation of the Enguri hydro power plant (HPP) 12 January 2009 Tbilisi Mayor Gigi Ugulava rules out early elections 12 January 2009 Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey visits Georgia to sign agreement with Georgian Foreign Minister Grigol Vashadze on the protection of Georgia’s interests in Russia by Switzerland 12 January 2009 Estonian President Toomas Hendrik Ilves visits Azerbaijan 13 January 2009 Opposition parties in Georgia criticize the government for striking -

2011-2012 CJFE's Review of Free Expression in Canada

2011-2012 CJFE’s Review of Free Expression in Canada LETTER FROM THE EDITORS OH, HOW THE MIGHTY FALL. ONCE A LEADER IN ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PEACEKEEPING, HUMAN RIGHTS AND MORE, CANADA’S GLOBAL STOCK HAS PLUMMETED IN RECENT YEARS. This Review begins, as always, with a Report Card that grades key issues, institutions and governmental departments in terms of how their actions have affected freedom of expres- sion and access to information between May 2011 and May 2012. This year we’ve assessed Canadian scientists’ freedom of expression, federal protection of digital rights and Internet JOIN CJFE access, federal access to information, the Supreme Court, media ownership and ourselves—the Canadian public. Being involved with CJFE is When we began talking about this Review, we knew we wanted to highlight a major issue with a series of articles. There were plenty of options to choose from, but we ultimately settled not restricted to journalists; on the one topic that is both urgent and has an impact on your daily life: the Internet. Think about it: When was the last time you went a whole day without accessing the membership is open to all Internet? No email, no Skype, no gaming, no online shopping, no Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, no news websites or blogs, no checking the weather with that app. Can you even who believe in the right to recall the last time you went totally Net-free? Our series on free expression and the Internet (beginning on p. 18) examines the complex free expression. relationship between the Internet, its users and free expression, access to information, legislation and court decisions. -

Georgia After Merabishvili's Arrest: a Ukraine Scenario?

No. 62 (515), 5 June 2013 © PISM Editors: Marcin Zaborowski (Editor-in-Chief) . Katarzyna Staniewska (Managing Editor) Jarosław Ćwiek-Karpowicz . Artur Gradziuk . Piotr Kościński Roderick Parkes . Marcin Terlikowski . Beata Wojna Georgia after Merabishvili’s Arrest: A Ukraine Scenario? Konrad Zasztowt The recent arrest of Vano Merabishvili, Georgia’s former prime minister, closest associate of President Mikheil Saakashvili and leader of the opposition, raise suspicions that the current government uses prosecutors as instruments of political persecution on its opponents. However, it is too early to compare this case with the case of Ukraine’s former prime minister, Yulia Tymoshenko, already rated as “selective justice” by the U.S., European Union and many international organisations. The EU should closely monitor the legal proceedings in Merabishvili’s case and put further pressure on Georgian authorities to force them to continue the reform of prosecutors’ offices and the judiciary. Since 21 May, the Secretary General of the Georgian opposition, United National Movement’s (UNM) Vano Merabishvili, has remained in custody. According to the prosecutor in charge of his case, the former prime minister is responsible for misspending more than €2.3 million in public funds on the UNM election campaign last year. The prosecutor claims the money was granted to UNM followers formally as part of a programme to reduce unemployment but in fact was aggregated for party use. Merabishvili is also accused of the misappropriation of a private villa in 2009 when he served as minister of Internal Affairs. According to the prosecutor, Merabishvili, using his political position, simply forced the owner to leave his house to the ministry, and later—while using the villa for private purposes—spent public money for its renovation. -

St. George Campus 2018-2019 POL459/2216Y: the Military

St. George Campus 2018-2019 POL459/2216Y: The Military Instrument of Foreign Policy Professor A. Braun [email protected] Office hours: Trinity College, Room #309N Munk School, 1 Devonshire Pl. Mondays, 12-1pm (other times by arrangement) Telephone: 416-946-8952 Synopsis: This combined undergraduate-graduate course analyzes the relationship of military force to politics. Nuclear war and deterrence, conventional war, revolutionary war, terrorism, counter-insurgency, cyberwar, and drone warfare are examined from the perspectives of the U.S., Russia, China, and other contemporary military powers. Foreign policy provides the context within which one should examine the existence of and the utility of the military instrument of foreign policy. And, as Henry Brandon has said, foreign policy begins at home. Therefore, the introductory part of the course deals with the theory and politics of civil-military relations and examines the military establishments of the major powers with special emphasis on those of the USA, Russia/CIS, and China. This section will also explore the problems of measuring equivalence. The second part investigates the various theories of conflict, the problems of nuclear war and deterrence, the diverse forms of conventional war, and the efficacy of war termination strategies. The final section contains case studies of some of these problems. The aim of this course is to help acquaint students of international relations with the vital importance of the military instrument in the formulation and implementation of foreign policy and in the functioning of the international system. It is also hoped that thus they will be able to employ additional tools of analysis in the study of international relations. -

Free and Fair? a Challenge for the EU As Georgia and Ukraine Gear up for Elections Hrant Kostanyan and Ievgen Vorobiov 27 September 2012

Free and fair? A Challenge for the EU as Georgia and Ukraine gear up for elections Hrant Kostanyan and Ievgen Vorobiov 27 September 2012 n an important test for democracy, Georgia and Ukraine will go to the polls for parliamentary elections on the 1st and 28th of October, respectively. The political leaders I of these two Eastern Partnership countries have committed themselves to European values and principles – rhetorically. In reality, the promise of their colour revolutions is unrealised and they have shifted further towards authoritarianism, albeit following different paths in their respective post-revolution periods. Georgian leader Mikheil Saakashvili has championed a number of important reforms such as fighting criminality and improving public sector services. But democracy is in decline in the country, with an increasingly over- bearing government, a weak parliament, non-independent judiciary and semi-free media. Unlike Saakashvili, who is still at the helm of Georgian politics, the protagonists of the Ukrainian revolution have either been imprisoned (Yulia Tymoshenko) or discredited (Viktor Yushchenko). President Yushchenko’s attempts to neutralise his former revolutionary ally Tymoshenko resulted in the electoral victory of Viktor Yanukovych in 2010, who was quick to consolidate his reign. An uneven playing field The parliamentary elections in Georgia come at a critical juncture for the country, because the constitutional changes to be enforced in 2013 significantly increase the powers of the prime minister – effectively transforming this election into ‘king-maker’. If the Ukrainian president is to secure a constitutional majority in parliament, there are indications that Yanukovych will push for an amendment to enable presidential election by parliament rather than by direct popular vote. -

![Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0690/georgia-republic-recent-developments-and-u-s-1850690.webp)

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S

Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs May 18, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov 97-727 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Georgia [Republic]: Recent Developments and U.S. Interests Summary The small Black Sea-bordering country of Georgia gained its independence at the end of 1991 with the dissolution of the former Soviet Union. The United States had an early interest in its fate, since the well-known former Soviet foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, soon became its leader. Democratic and economic reforms faltered during his rule, however. New prospects for the country emerged after Shevardnadze was ousted in 2003 and the U.S.-educated Mikheil Saakashvili was elected president. Then-U.S. President George W. Bush visited Georgia in 2005, and praised the democratic and economic aims of the Saakashvili government while calling on it to deepen reforms. The August 2008 Russia-Georgia conflict caused much damage to Georgia’s economy and military, as well as contributing to hundreds of casualties and tens of thousands of displaced persons in Georgia. The United States quickly pledged $1 billion in humanitarian and recovery assistance for Georgia. In early 2009, the United States and Georgia signed a Strategic Partnership Charter, which pledged U.S. support for democratization, economic development, and security reforms in Georgia. The Obama Administration has pledged continued U.S. support to uphold Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The United States has been Georgia’s largest bilateral aid donor, budgeting cumulative aid of $2.7 billion in FY1992-FY2008 (all agencies and programs). -

Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post- Socialist Southeastern Europe

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15912-9 — Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe Edited by Sabrina P. Ramet , Marko Valenta Frontmatter More Information i Ethnic Minorities and Politics in Post-Socialist Southeastern Europe Southeast European politics cannot be understood without taking into account ethnic minorities. This book provides a comprehensive introduction to the politics of ethnic minorities, examining both their political parties and issues of social distance, migration, and ethnic boundaries, as well as issues related to citizenship and integration. Coverage includes detailed analyses of Hungarian minority parties in Romania, Albanian minority parties in Macedonia, Serb minority par- ties in Croatia, Bosniak minority parties in Serbia, and various minor- ity parties in Montenegro, as well as the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, a largely Turkish party, in Bulgaria. Sabrina P. Ramet is a professor of Political Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, in Trondheim, Norway. Born in London, England, she was educated at Stanford University, the University of Arkansas, and UCLA, receiving her Ph.D. in Political Science from UCLA in 1981. She is the author of twelve scholarly books (three of which have been published in Croatian translations) and edi- tor or co- editor of thirty- two published books. Her books can also be found in French, German, Italian, Macedonian, Polish, and Serbian translations. Her latest book is Gender (In)equality and Gender Politics in Southeastern Europe: A question of justice , co- edited with Christine M. Hassenstab (2015). Marko Valenta is a sociologist and a Professor at the Department of Social Work and Health Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, in Trondheim, Norway. -

The Russo-Georgian Relationship: Personal Issues Or National Interest?

THE RUSSO-GEORGIAN RELATIONSHIP: PERSONAL ISSUES OR NATIONAL INTEREST? The Russian-Georgian conflict over South Ossetia in 2008 brought renewed international interest in the South Caucasus. Since the conflict, the Russo- Georgian relationship remains tense and is characterized by threats, recrimi- nations, and mutual suspicion. Those who ignore historical events between Georgia and Russia, assume the personal relationship between the leaders of the two countries is the source of confrontation. This article argues that while personal factors certainly play some role in the “poisonous” relations between the neighboring states, clashing national interests, ideological differ- ences of ruling elites and other important factors also feed into this situation. Kornely K. Kakachia* * Kornely K. Kakachia is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Tbilisi State University and presently a Visiting Scholar at the Harriman Institute of Columbia University. 109 VOLUME 9 NUMBER 4 KORNELY K. KAKACHIA he course of history is determined by the decision of political elites. Leaders and the kind of leadership they exert shape the way in which foreign policies are structured. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s view, that “there is properly no history, only biography,” encapsulates the view that individual leaders mold history. Some political scientists view “rational choice” as the driving force behind individual decisions, while economists see choices as shaped by market forces. Yet, many observers are more impressed by the myste- rious aspects of the decision-making process, curious about what specific factors may determine a given leader’s response to events. The military conflict between Georgia and Russia over Georgia’s separatist region of South Ossetia in August 2008 surprised many within the international community and reinforced growing concerns about increasingly antagonistic relations between these two neighbors.