Someone Who Learns About the Past by Finding and Studying the Remains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hereward and the Barony of Bourne File:///C:/Edrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/Hereward.Htm

hereward and the Barony of Bourne file:///C:/EDrive/Medieval Texts/Articles/Geneaology/hereward.htm Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 29 (1994), 7-10. Hereward 'the Wake' and the Barony of Bourne: a Reassessment of a Fenland Legend [1] Hereward, generally known as 'the Wake', is second only to Robin Hood in the pantheon of English heroes. From at least the early twelfth century his deeds were celebrated in Anglo-Norman aristocratic circles, and he was no doubt the subject of many a popular tale and song from an early period. [2] But throughout the Middle Ages Hereward's fame was local, being confined to the East Midlands and East Anglia. [3] It was only in the nineteenth century that the rebel became a truly national icon with the publication of Charles Kingsley novel Hereward the Wake .[4] The transformation was particularly Victorian: Hereward is portrayed as a prototype John Bull, a champion of the English nation. The assessment of historians has generally been more sober. Racial overtones have persisted in many accounts, but it has been tacitly accepted that Hereward expressed the fears and frustrations of a landed community under threat. Paradoxically, however, in the light of the nature of that community, the high social standing that the tradition has accorded him has been denied. [5] The earliest recorded notice of Hereward is the almost contemporary annal for 1071 in the D version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. A Northern recension probably produced at York,[6] its account of the events in the fenland are terse. It records the plunder of Peterborough in 1070 'by the men that Bishop Æthelric [late of Durham] had excommunicated because they had taken there all that he had', and the rebellion of Earls Edwin and Morcar in the following year. -

Anglo- Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066

1.1 Anglo- Saxon society Key topic 1: Anglo- Saxon England and 1.2 The last years of Edward the Confessor and the succession crisis the Norman Conquest, 1060-1066 1.3 The rival claimants for the throne 1.4 The Norman invasion The first key topic is focused on the final years of Anglo-Saxon England, covering its political, social and economic make-up, as well as the dramatic events of 1066. While the popular view is often of a barbarous Dark-Ages kingdom, students should recognise that in reality Anglo-Saxon England was prosperous and well governed. They should understand that society was characterised by a hierarchical system of government and they should appreciate the influence of the Church. They should also be aware that while Edward the Confessor was pious and respected, real power in the 1060s lay with the Godwin family and in particular Earl Harold of Wessex. Students should understand events leading up to the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066: Harold Godwinson’s succession as Earl of Wessex on his father’s death in 1053 inheriting the richest earldom in England; his embassy to Normandy and the claims of disputed Norman sources that he pledged allegiance to Duke William; his exiling of his brother Tostig, removing a rival to the throne. Harold’s powerful rival claimants – William of Normandy, Harald Hardrada and Edgar – and their motives should also be covered. Students should understand the range of causes of Harold’s eventual defeat, including the superior generalship of his opponent, Duke William of Normandy, the respective quality of the two armies and Harold’s own mistakes. -

Securing the Kingdom 1066-87

HISTORY – YEAR 10 – WILLIAM I IN POWER: SECURING THE KINGDOM 1066- 1087 A KEY DATES C KEY TERMS The outer part of the castle, surrounding the motte and protected by 1 Bailey 1 1068 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar. a fence or wall. When one country encourages the migration of its people to another 2 Colonisation 2 1069 Rebellions in the north. country. The governor of a castle and its surrounding lands (castlery); its lord Castellan 3 1069-70 The Harrying of the North. 3 or a steward of the local lord. Cutting someone off from the church community so that they are 4 1070-71 Hereward the Wake and the revolt at Ely. unable to confess their sins before they die, which people believed 4 Excommunication would stop them from going to heaven. It was not intended to be 5 1075 The Revolt of the Earls. permanent but to punish someone to make them act correctly to rejoin the church. 1077-80 William in conflict with his son Robert. To lose something as a punishment for committing a crime or bad 6 Forfeit 5 action. 1087 Death of William I. A deliberate and organized attempt to exterminate an entire group of 7 Genocide 6 people. 8 1088 Rebellions against William II. When small bands attack a larger force by surprise and then Guerilla War 7 disappear back into the local population. It is a modern term. 9 1088 Rebellions failed. Odo exiled and disinherited. An archaic (old) word meaning to lay waste to something and to Harrying 8 devastate it. -

Anglo–Saxon and Norman England

GCSE HISTORY Anglo–Saxon and Norman England Module booklet. Your Name: Teacher: Target: History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 Checklist Anglo-Saxon society and the Norman conquest, 1060-66 Completed Introduction to William of Normandy 2-3 Anglo-Saxon society 4-5 Legal system and punishment 6-7 The economy and social system 8 House of Godwin 9-10 Rivalry for the throne 11-12 Battle of Gate Fulford & Stamford Bridge 13 Battle of Hastings 14-16 End of Key Topic 1 Test 17 William I in power: Securing the kingdom, 1066-87 Page Submission of the Earls 18 Castles and the Marcher Earldoms 19-20 Revolt of Edwin and Morcar, 1068 21 Edgar Aethling’s revolts, 1069 22-24 The Harrying of the North, 1069-70 25 Hereward the Wake’s rebellion, 1070-71 26 Maintaining royal power 27-28 The revolt of the Earls, 1075 29-30 End of Key Topic 2 Test 31 Norman England, 1066-88 Page The Norman feudal system 32 Normans and the Church 33-34 Everyday life - society and the economy 35 Norman government and legal system 36-38 Norman aristocracy 39 Significance of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux 40 William I and his family 41-42 William, Robert and revolt in Normandy, 1077-80 43 Death, disputes and revolts, 1087-88 44 End of Key Topic 3 test 45 1 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 2 History Module Booklet – U2B- Anglo-Saxon & Norman England, 1060-88 KT1 – Anglo-Saxon society and the Normans, 1060-66 Introduction On the evening of 14 October 1066 William of Normandy stood on the battlefield of Hastings. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

THE NORMAN CONQUEST Late Jan 1066 – William Started to Build a Fleet Year the French-Speaking William of Normandy Was in and Gathered His Army Together Charge

OVERVIEW HISTORY KNOWLEDGE 1066 TIMELINE In 1066 the King of England, Edward the Confessor, ORGANISER 5th Jan 1066 – Edward the Confessor died died without an heir. Three men all competed for the th YEAR 7 – TERM 2 6 Jan 1066 – Godwinson crowned King throne, resulting in two key battles. By the end of the THE NORMAN CONQUEST Late Jan 1066 – William started to build a fleet year the French-speaking William of Normandy was in and gathered his army together charge. th 12 Aug 1066 – William was ready to depart Many Saxons rebelled against their new King as he Late May 1066 – Tostig arrived in England was an invading foreigner. William had to work hard 18th Sept 1066 – Hardrada arrived to gain full control of his new kingdom, and it took 25th Sept 1066 – Battle of Stamford Bridge him 5 years to gain control over the whole country. 28th Sept 1066 – William arrived in England He used various methods, including terror as well as nd rewarding loyalty. A new system of taxation also 2 Oct 1066 – Godwinson began marching south made him a rich and powerful king. 13th Oct 1066 – Godwinson arrived at Hastings KEY TERMS 14th Oct 1066 – Battle of Hastings KEY INDIVIDUALS Bayeux Tapestry – a Norman embroidery 25th Dec 1066 – William crowned at Edward the Confessor - Saxon King of England who depicting the events of 1066 Westminster Abbey died in 1066 without an heir Cavalry – soldiers on horseback Claimants – people who believed they had Harold Godwinson - Saxon noble who became King a right to the throne WILLIAM’S METHODS OF CONTROL when Edward died Conquest – to take over a country The Harrying of the North – the destruction of villages Harald Hardrada - King of Norway who invaded in Coronation – ceremony to crown a and crops in the North of England where rebellions 1066 and lost the Battle of Stamford Bridge monarch Heir – a person who inherits something. -

The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the Family, the Fief and the Feudal Monarchy*

© K.S.B. Keats-Rohan 1991. Published Nottingham Mediaeval Studies 36 (1992), 42-78 The Bretons and Normans of England 1066-1154: the family, the fief and the feudal monarchy* In memoriam R.H.C.Davis 1. The Problem (i) the non-Norman Conquest Of all the available studies of the Norman Conquest none has been more than tangentially concerned with the fact, acknowledged by all, that the regional origin of those who participated in or benefited from that conquest was not exclusively Norman. The non-Norman element has generally been regarded as too small to warrant more than isolated comment. No more than a handful of Angevins and Poitevins remained to hold land in England from the new English king; only slightly greater was the number of Flemish mercenaries, while the presence of Germans and Danes can be counted in ones and twos. More striking is the existence of the fief of the count of Boulogne in eastern England. But it is the size of the Breton contingent that is generally agreed to be the most significant. Stenton devoted several illuminating pages of his English Feudalism to the Bretons, suggesting for them an importance which he was uncertain how to define.1 To be sure, isolated studies of these minority groups have appeared, such as that of George Beech on the Poitevins, or those of J.H.Round and more recently Michael Jones on the Bretons.2 But, invaluable as such studies undoubtedly are, they tend to achieve no more for their subjects than the status of feudal curiosities, because they detach their subjects from the wider question of just what was the nature of the post-1066 ruling class of which they formed an integral part. -

Norman Consolidation of Power Level

Key Words, Week 1: Key Individuals, Week 2: History, Y9 T1b: Norman Consolidation of Power Revolt A rebellion against the ruler of a country William the Norman king of England, ruled from 1066 (those rebelling are known as rebels). Conqueror to 1087. Level: Grade 5 (compulsory) Regent A trusted advisor to the king that was allowed Edwin and Morcar Anglo-Saxon earls of Mercia and to run the country while he was absent. Northumbria. Submitted in 1066, but later Key dates, Week 3: th Motte and A castle which was easy to build, used by the rebelled multiple times. 25 Dec William crowned king at Westminster bailey Normans to control England soon after the Edgar Atheling An Anglo-Saxon claimant to the throne. 1066 Abbey. Conquest. Allied with the Scots and the Danes to Aug A major rebellion in the north, led by Landholder The person that lives on the land, effectively fight William. 1068 Edwin and Morcar. renting it from the king. Robert de A Norman earl, given the job of subduing Jan 1069 Robert de Comines was burned to death Landowner The person who actually owns the land. After Comines Northumbria. Burned to death by rebels. by rebels in Durham. 1066, the king was the only landowner in Hereward the An Anglo-Saxon thegn and rebel who took Sept The Danes invaded and supported the England. Wake Ely. 1069 Anglo-Saxon rebellion, led by Edgar. Tenure The process by which you held land from the William fitzOsbern Loyal followers of William and his regents Oct 1069 William paid off the Danes and defeated king. -

Hereward the Wake and the Rebellion at Ely 1070-71 • in 1070 King Sweyn of Denmark Returned with a Fleet to England • Sweyn

Hereward the Wake and the rebellion at Ely 1070-71 • In 1070 King Sweyn of Denmark returned with a fleet to England • Sweyn went to the Isle of Ely in East Anglia • This area was a marshy/swampy region in the east of England, it was difficult ground where local knowledge of safe paths was essential • King Sweyn joined up with English rebels who were also based at Ely led by a rebel leader named Hereward the Wake, he was a local thegn (local lord), he’d been exiled under Edward the Confessor and when he came back in 1069 he found his land had been given to a Norman. • Hereward used the treacherous (awful) terrain (ground) to his advantage and began fighting a guerrilla war • The Danes & Hereward raided Peterborough Abbey together. They did not want its riches falling into the hands of the Normans. The Danes though then sailed off with the treasure back to Denmark • Morcar joined Hereward (Edwin had been murdered by this point). • William then surrounded the island of Ely and built a causeway so his men could cross. William bribed local monks to show them a safe way through the marshes. The first attempt failed and his men drowned when the bridge collapsed but the second attempt was more successful. • During the fighting Hereward escaped and was not heard of again. Morcar was imprisoned, prisoners were dealt with harshly (eyes put out, feet and hands cut off). • This rebellion marked the end of the large-scale Anglo Saxon rebellions. Hereward the Wake and the rebellion at Ely 1070-71 • In 1070 King Sweyn of Denmark returned with a fleet to England • Sweyn went to the Isle of Ely in East Anglia • This area was a marshy/swampy region in the east of England, it was difficult ground where local knowledge of safe paths was essential • King Sweyn joined up with English rebels who were also based at Ely led by a rebel leader named Hereward the Wake, he was a local thegn (local lord), he’d been exiled under Edward the Confessor and when he came back in 1069 he found his land had been given to a Norman. -

Richmondshire District Council Offices

RICHMOND Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Proposals Draft Contents PART 1: APPRAISAL PART 2: MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS PART 1: APPRAISAL Appraisal .............................................................................................................................................1 Statement of Significance ............................................................................................................................1 Location and Setting ...................................................................................................................................2 Historic Development .....................................................................................................................2 Archaeology .......................................................................................................................................3 Architecture and Building Materials ..........................................................................................4 Architectural Style of Properties ...............................................................................................................4 Vernacular .......................................................................................................................................4 Landmark and historically significant buildings ....................................................................................5 - The Castle ...........................................................................................................................5 -

The Norman Conquest

OCR SHP GCSE THE NORMAN CONQUEST NORMAN THE OCR SHP 1065–1087 GCSE THE NORMAN MICHAEL FORDHAM CONQUEST 1065–1087 MICHAEL FORDHAM The Schools History Project Set up in 1972 to bring new life to history for school students, the Schools CONTENTS History Project has been based at Leeds Trinity University since 1978. SHP continues to play an innovatory role in history education based on its six principles: ● Making history meaningful for young people ● Engaging in historical enquiry ● Developing broad and deep knowledge ● Studying the historic environment Introduction 2 ● Promoting diversity and inclusion ● Supporting rigorous and enjoyable learning Making the most of this book These principles are embedded in the resources which SHP produces in Embroidering the truth? 6 partnership with Hodder Education to support history at Key Stage 3, GCSE (SHP OCR B) and A level. The Schools History Project contributes to national debate about school history. It strives to challenge, support and inspire 1 Too good to be true? 8 teachers through its published resources, conferences and website: http:// What was Anglo-Saxon England really like in 1065? www.schoolshistoryproject.org.uk Closer look 1– Worth a thousand words The wording and sentence structure of some written sources have been adapted and simplified to make them accessible to all pupils while faithfully preserving the sense of the original. 2 ‘Lucky Bastard’? 26 The publishers thank OCR for permission to use specimen exam questions on pages [########] from OCR’s GCSE (9–1) History B (Schools What made William a conqueror in 1066? History Project) © OCR 2016. OCR have neither seen nor commented upon Closer look 2 – Who says so? any model answers or exam guidance related to these questions. -

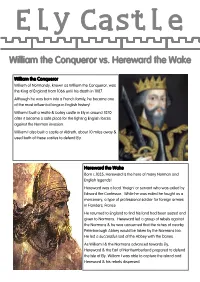

William the Conqueror Vs. Hereward the Wake

Ely Castle William the Conqueror vs. Hereward the Wake William the Conqueror William of Normandy, known as William the Conqueror, was the King of England from 1066 until his death in 1087. Although he was born into a French family, he became one of the most influential kings in English history! William I built a motte & bailey castle in Ely in around 1070 after it became a safe place for the fighting English forces against the Norman invasion. William I also built a castle at Aldreth, about 10 miles away & used both of these castles to defend Ely. Hereward the Wake Born c.1035, Hereward is the hero of many Norman and English legends! Hereward was a local 'theign' or servant who was exiled by Edward the Confessor. While he was exiled he fought as a mercenary, a type of professional soldier for foreign armies in Flanders, France. He returned to England to find his land had been seized and given to Normans. Hereward led a group of rebels against the Normans & he was concerned that the riches of nearby Peterborough Abbey would be taken by the Normans too. He led a successful raid of the Abbey with the Danes. As William I & the Normans advanced towards Ely, Hereward & the Earl of Northumberland prepared to defend the Isle of Ely. William I was able to capture the island and Hereward & his rebels dispersed. Ely Castle The castle in Ely was originally a wooden motte and bailey castle. It was re-fortified in the 12th Century before being finally destroyed in the mid 13th Century.