Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engthen the Internal Control System in Agencies Towards Better Performance

Ël-gZuN-−is-Zib-dbN-'²in; ROYAL AUDIT AUTHORITY RAA(AAR-2003)/1558 Dated: 17th May, 2004 Foreword “Every individual must strive to be principled. And individuals in positions of responsibility must even strive harder”. HRH The Crown Prince Dasho Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The year 2003 concluded with a historic victory of good over evil when under His Majesty’s personal participation the nation rid of the menace of invasive terrorism. The success came at a time when other nations falter and at least found ineffective to tackle the malaise of the evils of terror. The Annual Audit Report 2003 (AAR 2003) is an account of one year’s of service under the rule of His Majesty to fight the menace within the society. His Majesty’s vision of a complete nation we believe is one safe from external threat and aggression; and morally and ethically a correct society internally. We hope in this framework this report reinforces the national efforts to safeguard the national integrity and further enhances the quality of governance of Bhutan. We are happy to report in the year 2003, the Royal Audit Authority had conducted 203 normal audits, 5 special audits, 69 project certifications and 17 statutory audits. During the same year the RAA had transmitted a total of 275 audit reports including 184 inspection reports, 6 special audit reports, 68 project certifications and 17 statutory audit reports. This report mainly contains the significant audit findings and observations contained in the Inspection Reports that were issued within the calendar year 2003 as presented in the Annexure. -

Telephone Directory

BUMTHANG: ARE A CODE - 03 Accounts Section ..............................................631805 BUMTHANG GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONS Store .................................................................631936 EMERGENCY & ESSENTIAL SERVICE Workshop In-Charge ........................................631690 Equipment In-Charge .......................................631694 NUMBERS BUMTHANG Ambulance.............................................................. 112 DEPARTMENT OF LIVESTOCK Fire/Police/Traffic .................................................... 113 National Horse & Brown Swiss Cross Breeding Telephone Complaint .............................................. 114 Manager .................631158/631761/631466/F-631836 Telephone Directory Enquiry ................................1600 Brown Swiss Cattle & Horse Farm RABDEY DRATSHANG Farm Manager ..................................631238/F-631838 KURJEY LHAKHANG General Office ..................................................631801 Lam Neten ........................................................ 631152 Drungchen ........................................................ 631137 Kurjey Lhakhang, Dzongpon ............................631485 National Horse Farm Manager .................................631457/631466/631686 JAKAR DZONG Jakar Lam .........................................................631294 Royal Veterinary Laboratory General Office ..................................................631538 Veterinary Hospital ...........................................631745 Clerk .................................................................631566 -

The Changing Status of Women in Modern Bhutan with Relation to Education (From 1914 to 2003 A.D.)

Karatoya: NBU ). Hist. Vol. 9 ISSN: 2229-4880 The Changing Status of Women in Modern Bhutan with Relation to Education (From 1914 to 2003 A.D.) Ratna Paul 1 Abstract: Till the middle of the last century Bhutan was isolated from the outside world and its social system was feudal. Historically, women were supposed to enjoy the same legal status as men, but after looking at the records and the practical aspects ofwomen's lives we find that is not so true and practically their role was only of a home maker. The advancement and emancipation of women is virtually a recent phenomenon. Before the advent of modern education in the 1960s, the only form of education prevalent was traditional monastic education where Jew women got opportunity to educate themselves. Although the seed of modern school system to impart secular education was sown in 1914, women's entry in the formal education came about only after many years. We must, ofcourse acknowledge that Bhutan was passing through a phase where parents preferred to send their sons to school rather than daughters not only because of harsh terrains, long distances, lack of accommodations or other general hardships but also because of the view that daughters were more vulnerable and more useful at home. In the 1960s with the Royal Government's intention to modernize the country, Five Year Plans were implemented and as a part of these plans, literacy rate was sought to be increased, and women found the doors ofschools unlocked to educate themselves. Gradually the number of schools increased, so also the number of girl students. -

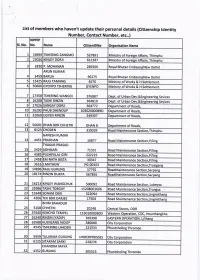

The List of the Members

List of members who haven't update their personal details (citizenship ldentity Number, Contact Number, etc..) NPPFP Sl, No. No, Name CitizenlDNo Organisation Name 1 16959 TSHERING ZANGMO 527891 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Thimphu 2 23026 KINLEY DORJI 611387 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Thimphu 3 2830 P. MOHANAN 285566 Royal Bhutan Embassy(New Delhi) ARUN KUMAR 4 3459 BARUA 96175 Royal Bhutan Embassy(New Delhi) 5 L3425 RNU TAMANG 4570 Ministry of Works & H.Settlement. 6 s0600 GYENPO TSHERING GYENPO Ministry of Works & H.Settlement. 7 27458 TSHERING WANGDI 576887 Dept. of Urban Dev.&Engineering Sevices 8 16208 TASHI RINZIN 364819 Dept. of Urban Dev.&En st neering Sevlces 9 L7026 SANGAY DORJI 364772 Department of Roads, 10 26292 PHUB DHENDUP 10302000089D Department of Roads, 11 22060 UGYEN RINZIN 349307 Department of Roads, t2 50501 DHAN BDR CHHETRI DHAN B Department of Roads 13 812 3 CHODEN 319205 Road Maintenance Section,Thim phu GANESH KUMAR t4 4457 PRADHAN 76877 Road Maintenance Section,P/ling THAKUR PRASAD 15 3429 ADHIKARI 71331 Road Maintenance Section,P/li ng 15 4385 PUSHPALAL GIRI 222225 Road Maintenance section ,P/ling L7 2458 EM NATH BISTA 30347 Road Maintenance Section,P/li n8 18 3615 J.MATHEW PG-00103 Road Maintenance Section,Trasi gang 19 14896 RNU GURUNG 17792 RoadMaintenance Section,Sar pang 20 l8t7 4 RINZIN DUKPA 567856 RoadMaintenance Section,Sar panS 2L 15213 KINLEY WANGCHUK 500092 Road Maintenance Sectio n, Lobeysa 22 25995 TASHI TOBGAY 11208001606 Road Maintenance Section,Tro nSsa 23 15548 SONAM DEKI 522094 Road Maintenance -

A Case for Investment

(c) 2017 ECCD & SEN Division, Ministry of Education, Kawajangsa, Thimphu, Bhutan UNICEF Bhutan Country Office, UN House, Peling Lam EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT IN BHUTAN P.O. Box 239, Kawajangsa, Thimphu, Bhutan A Case for Investment Photo credit: ECCD-SEN Division, Department of School Education, Ministry of Education and UNICEF Bhutan Designed and printed at Bhutan Printing Solutions (www.prints.bt) A CASE FOR INVESTMENT EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT IN BHUTAN A Case for Investment ECCD-SEN Division, Department of School Education, Ministry of Education and UNICEF Bhutan EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT IN BHUTAN “A nation’s future will mirror the quality of her youth — a nation cannot fool herself into thinking of a bright future when she has not invested wisely in her children.” — His Majesty King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck ii A CASE FOR INVESTMENT Foreword i EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT IN BHUTAN Acknowledgements This report is the outcome of the cooperation and collaboration of many individuals and organizations. In particular, immeasurable gratitude is extended to: Sangay Jamtsho, Ameena M. Didi, Bishnu B. Mishra, and Sherpem Sherpa from the UNICEF office in Bhutan for their invaluable inputs and support throughout the consultancy period; Elinor Bajraktari from the UNICEF Headquarters for his instrumental guidance and direction, especially in the technical aspects of the study; Sherab Phuntshok, Karma Gayleg, Chencho Wangdi, and Karma Choden from the ECCD and SEN Division of the Ministry of Education for their vital guidance and feedback throughout the process; Karma Dyenka and Parvati Sharma from Save the Children Bhutan for sharing their ECCD expenditure statements and ECCD Impact Study reports; the DEOs and national level ECCD stakeholders for their cooperation; and to Kuenley Tenzin, the Project Coordinator for the School Rationalization Project, for his support during field visits.