The School-To-Prison Pipeline and Uneven Emancipation in Jason Reynolds' Miles Morales: Spider-Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL COMICS... Amazing Spider-Man #16 Fantastic Four #7 Daredevil #2 Avengers No Road Home #3 (of 10) Superior Spider-Man #3 Age of X-Man X-Tremists #1 (of 5) Captain America #8 Captain Marvel Braver & Mightier #1 Savage Sword of Conan #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Betrayed #1 ($1) Invaders #2 True Believers Captain Marvel Avenger #1 ($1) Black Panther #9 X-Force #3 Marvel Comics Presents #2 True Believers Captain Marvel New Ms Marvel #1 ($1) West Coast Avengers #8 Spider-Man Miles Morales Ankle Socks 5-Pack Star Wars Doctor Aphra #29 Black Panther vs. Deadpool #5 (of 5) Marvel Previews Captain Marvel 2019 Sampler (FREE) Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #40 Mr. and Mrs. X Vol. 1 GN Spider-Geddon Covert Ops GN Iron Fist Deadly Hands of Kung Fu Complete Collection GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Peyer & Gutierrez GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Heroes in Crisis #6 (of 9) Flash #65 "The Price" part 4 (of 4) Detective Comics #999 Action Comics #1008 Batgirl #32 Shazam #3 Wonder Woman #65 Martian Manhunter #3 (of 12) Freedom Fighters #3 (of 12) Batman Beyond #29 Terrifics #13 Justice League Odyssey #6 Old Lady Harley #5 (of 5) Books of Magic #5 Hex Wives #5 Sideways #13 Silencer #14 Shazam Origins GN Green Lantern by Geoff Johns Book 1 GN Superman HC Vol. 1 "The Unity Saga" DC Essentials Nightwing Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Man-Eaters #6 Die Die Die #8 Outcast #39 Wicked & Divine #42 Oliver #2 Hardcore #3 Ice Cream Man #10 Spawn #294 Cold Spots GN Man-Eaters Vol. -

Graphic Novels for Children and Teens

J/YA Graphic Novel Titles The 9/11 Report: A Graphic Adaptation Sid Jacobson Hill & Wang Gr. 9+ Age of Bronze, Volume 1: A Thousand Ships Eric Shanower Image Comics Gr. 9+ The Amazing “True” Story of a Teenage Single Mom Katherine Arnoldi Hyperion Gr. 9+ American Born Chinese Gene Yang First Second Gr. 7+ American Splendor Harvey Pekar Vertigo Gr. 10+ Amy Unbounded: Belondweg Blossoming Rachel Hartman Pug House Press Gr. 3+ The Arrival Shaun Tan A.A. Levine Gr. 6+ Astonishing X-Men Joss Whedon Marvel Gr. 9+ Astro City: Life in the Big City Kurt Busiek DC Comics Gr. 10+ Babymouse Holm, Jennifer Random House Children’s Gr. 1-5 Baby-Sitter’s Club Graphix (nos. 1-4) Ann M. Martin & Raina Telgemeier Scholastic Gr. 3-7 Barefoot Gen, Volume 1: A Cartoon Story of Hiroshima Keiji Nakazawa Last Gasp Gr. 9+ Beowulf (graphic adaptation of epic poem) Gareth Hinds Candlewick Press Gr. 7+ Berlin: City of Stones Berlin: City of Smoke Jason Lutes Drawn & Quarterly Gr. 9+ Blankets Craig Thompson Top Shelf Gr. 10+ Bluesman (vols. 1, 2, & 3) Rob Vollmar NBM Publishing Gr. 10+ Bone Jeff Smith Cartoon Books Gr. 3+ Breaking Up: a Fashion High graphic novel Aimee Friedman Graphix Gr. 5+ Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Season 8) Joss Whedon Dark Horse Gr. 7+ Castle Waiting Linda Medley Fantagraphics Gr. 5+ Chiggers Hope Larson Aladdin Mix Gr. 5-9 Cirque du Freak: the Manga Darren Shan Yen Press Gr. 7+ City of Light, City of Dark: A Comic Book Novel Avi Orchard Books Gr. -

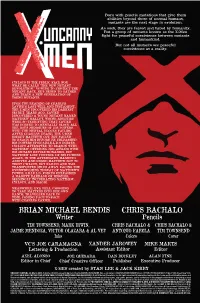

Brian Michael Bendis Chris Bachalo

Born with genetic mutations that give them abilities beyond those of normal humans, mutants are the next stage in evolution. As such, they are feared and hated by humanity. But a group of mutants known as the X-Men fight for peaceful coexistence between mutants and humankind. But not all mutants see peaceful coexistence as a reality. CYCLOPS IS THE PUBLIC FACE FOR WHAT HE CALLS “THE NEW MuTANT REVOLuTION.” VOWING TO PROTECT THE MuTANT RACE, HE’S BEGuN TO GATHER AND TRAIN A NEW GENERATION OF YOUNG MUTANTS. UPON THE READING OF CHARLES XAVIER’S LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT, THE X-MEN UNCOVERED HIS DARKEST SECRET. YEARS AGO, XAVIER DISCOVERED A YOUNG MUTANT NAMED MATTHEW MALLOY, WHOSE ABILITIES WERE SO TERRIFYING THAT XAVIER WAS FORCED TO MENTALLY BLOCK ALL THE BOY’S MEMORIES OF HIS POWERS. WITH THE MENTAL BLOCKS FAILING AFTER CHARLES’ DEATH, THE x-MEN SOUGHT MATTHEW OUT, BUT FAILED TO REACH HIM BEFORE HE UNLEASHED HIS POWERS uPON S.H.I.E.L.D.’S FORCES. CYCLOPS ATTEMPTED TO REASON WITH MATTHEW, OFFERING HIM ASYLUM WITH HIS MUTANT REVOLUTIONARIES, BUT MATTHEW LOST CONTROL OF HIS POWERS AGAIN. IN THE AFTERMATH, MAGNETO ARRIVED AND URGED MATTHEW NOT TO TRUST CYCLOPS, BUT FAILED AND WAS TRANSPORTED MILES AWAY. FACING THE OVERWHELMING THREAT OF MATTHEW’S POWER, S.H.I.E.L.D. FORCES UNLEASHED A MASSIVE BARRAGE OF MISSILES, SEEMINGLY INCINERATING MATTHEW, CYCLOPS, AND MAGIK. MEANWHILE, EVA BELL, CHOOSING TO TAKE MATTERS INTO HER OWN HANDS, TRAVELLED BACK IN TIME, COMING FACE-TO-FACE WITH CHARLES XAVIER. BRIAN MICHAEL BENDIS CHRIS BACHALO Writer Pencils TIM TOWNSEND, MARK IRWIN, CHRIS BACHALO & CHRIS BACHALO & JAIME MENDOZA, VICTOR OLAZABA & AL VEY ANTONIO FABELA TIM TOWNSEND Inks Colors Cover VC’S JOE CARAMAGNA XANDER JAROWEY MIKE MARTS Lettering & Production Assistant Editor Editor AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE Editor in Chief Chief Creative Officer Publisher Executive Producer X-MEN created by STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY X-MEN No. -

Mar Customer Order Form

OrdErS PREVIEWS world.com duE th 18MAR 2013 MAR COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Mar Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 3:35:28 PM Available only STAR WARS: “BOBA FETT CHEST from your local HOLE” BLACK T-SHIRT comic shop! Preorder now! MACHINE MAN THE WALKING DEAD: ADVENTURE TIME: CHARCOAL T-SHIRT “KEEP CALM AND CALL “ZOMBIE TIME” Preorder now! MICHONNE” BLACK T-SHIRT BLACK HOODIE Preorder now! Preorder now! 3 March 13 COF Apparel Shirt Ad.indd 1 2/7/2013 10:05:45 AM X #1 kiNG CoNaN: Dark Horse ComiCs HoUr oF THe DraGoN #1 Dark Horse ComiCs GreeN Team #1 DC ComiCs THe moVemeNT #1 DoomsDaY.1 #1 DC ComiCs iDW PUBlisHiNG THe BoUNCe #1 imaGe ComiCs TeN GraND #1 UlTimaTe ComiCs imaGe ComiCs sPiDer-maN #23 marVel ComiCs Mar13 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 2/7/2013 2:21:38 PM Featured Items COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Mouse Guard: Legends of the Guard Volume 2 #1 l ARCHAIA ENTERTAINMENT Uber #1 l AVATAR PRESS Suicide Risk #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Clive Barker’s New Genesis #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Marble Season HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Black Bat #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 1 1 Battlestar Galactica #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Grimm #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Wars In Toyland HC l ONI PRESS INC. The From Hell Companion SC l TOP SHELF PRODUCTIONS Valiant Masters: Shadowman Volume 1: The Spirits Within HC l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Rurouni Kenshin Restoration Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Soul Eater Soul Art l YEN PRESS BOOKS & MAGAZINES 2 Doctor Who: Who-Ology Official Miscellany HC l DOCTOR WHO / TORCHWOOD Doctor Who: The Official -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL... Star Wars Vader Dark Visions #1 (Of

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL... Star Wars Vader Dark Visions #1 (of 5) Amazing Spider-Man #16.HU Avengers #16 (War of Realms) Avengers No Road Home #4 (of 10) Conan the Barbarian #4 Cosmic Ghost Rider Destroys Marvel History #1 (of 6) Uncanny X-Men #13 Domino Hotshots #1 (of 5) Immortal Hulk #14 Age of X-Man Prisoner-X #1 (of 5) Meet the Skrulls #1 (of 5) Star Wars #62 Champions #3 Deadpool #10 Miles Morales Spider-Man #1 (3rd print) Star Wars Age of Republic Padme Amidala #1 Black Order #5 (of 5) Fantastic Four Vol. 1 "Fourever" GN Killmonger #5 (of 5) Immortal Hulk #12 (2nd print) Ziggy Pig Silly Seal Comics #1 Avengers by Jason Aaron Vol. 2 GN Marvel Knights Punisher by Ennis Complete Collection Vol. 2 GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Detective Comics 80 Years of Batman Deluxe Hard Cover Doomsday Clock #9 (of 12) Batman #66 Green Lantern #5 Justice League #19 Harley Quinn #59 Young Justice #3 Adventures of the Super Sons #8 (of 12) Deathstroke #41 Green Arrow #50 Female Furies #2 (of 6) Dreaming #7 Curse of Brimtstone #12 Suicide Squad Black Files #5 (of 6) Batman & Harley Quinn GN Justice League Dark Vol. 1 GN JLA New World Order Essential Edition GN DC Essentials Batgirl Action Figure NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... Walking Dead #189 Walking Dead Vol. 31 GN Die #4 Cemetery Beach #7 (of 7) Deadly Class #37 Paper Girls #26 Unnatural #8 (of 12) Self Made #4 Eclipse #13 Vindication #2 (of 4) Last Siege GN Wicked & Divine Vol. -

Pretty Good Quality

Contents Digging up the Future ....................................................................................................3 Registration .................................................................................................................4 Volunteering................................................................................................................4 Opening and Closing Ceremonies.....................................................................................4 Convention Policies.......................................................................................................5 Kids’ Programming ........................................................................................................5 Alastair Reynolds – Writer Guest of Honor .........................................................................7 Wayne Douglas Barlowe – Artist Guest of Honor ............................................................... 11 Shawna McCarthy – Editor Guest of Honor....................................................................... 15 Nate Bucklin – Fan Guest of Honor ................................................................................ 16 Programming ............................................................................................................. 19 Film Room ................................................................................................................ 28 Concert Schedule....................................................................................................... -

Earthy Visions: Organic Fantasy, the Chthulucene, and the Decomposition of Whiteness in Nnedi Okorafor’S Children’S Speculative Fiction

Earthy Visions: Organic fantasy, the Chthulucene, and the Decomposition of Whiteness in Nnedi Okorafor’s Children’s Speculative Fiction Okorafor’s speculative children’s fiction makes important inroads in the work of decentering whiteness as a hegemonic construct. Her use of science fiction and fantasy to explore futures that resist colonization and the white imagination offer new visions of society and racialized identities. However, I argue that her fiction goes further than decentering whiteness. It begins the process of decomposing whiteness. In my paper, I use Okorafor’s children’s speculative fiction Zahrah the Windseeker and Akata Witch to question and extend Donna Haraway’s writings on the Chthulucene—a reframing of interspecies interaction as an earthy process carried out by subterranean, “chthonic ones.” According to Haraway, this interspecies interaction is a “tentacular process” that results in sym-poises, or making-with. The human, according to Haraway, becomes humus, or decomposing matter. In viewing Haraway through the lens of Okorafor, however, I point out how the concept of the Chthulucene rests in colorblind notions of the human (or species). I adapt Okorafor’s concept of organic fantasy, “fantasy that grows out of its own soil,” by connecting her symbolism of organic with Haraway’s foundation of the subterranean. Soil meets soil. In this paper, I first trace Okorafor’s ecological, earthy images in her children’s novels and show how those images critique whiteness, white futures, and white space. I then place Okorafor’s organic fantasy in conversation with Haraway, illustrating how organic fantasy unearths the colorblindness in the Chthulucene. -

NEW THIS WEEK from MARVEL... Spider-Woman #1 Outlawed #1

NEW THIS WEEK FROM MARVEL... Spider-Woman #1 Outlawed #1 Star Wars #4 Guardians of the Galaxy #3 Fantastic Four #20 Captain Marvel #16 Captain America #20 Excalibur #9 X-Force #9 Deadpool #4 Morbius #5 Amazing Mary Jane #6 Marvels X #3 (of 6) 2020 Iron Age #1 Atlantis Attacks #3 (of 5) Conan the Barbarian #14 Ghost-Spider #8 Valkyrie Jane Foster #9 Runaways #31 2020 Machine Man #2 (of 2) Aero #9 Thor #3 (2nd print) Star Wars Rise of Kylo Ren #2 (3rd print) Star Wars Rise of Kylo Ren #3 (2nd print) "Dollar" Empyre Galactus "Dollar" Empyre Swordman Taskmaster the Right Price GN Immortal Hulk Vol. 6 GN King Thor GN Conan the Barbarian Vol. 2 GN X-Men Milestones Messiah Complex GN Into the Spider-Verse Casual Miles Morales Funko-Pop NEW THIS WEEK FROM DC... Robin 80th Anniversary 100-Page Super Spectacular #1 Batman #91 Dceased Unkillables #2 (of 3) Justice League #43 Nightwing #70 Year of the Villain Hell Arisen #4 (of 4) Brave and the Bold #28 Facsimile Edition Aquaman #58 Plunge #2 (of 6) Teen Titans #40 1 Titans Giant Low Low Woods #4 (of 6) Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #9 (of 12) He Man and the Masters of the Multiverse #5 (of 6) Lucifer #18 Dollar Comics Justice League #1 (1987) Dollar Comics JLA #1 Superman Vol. 2 GN NEW THIS WEEK FROM IMAGE... 18 Undiscovered Country #5 Tartarus #2 Family Tree #5 Middlewest #16 Ascender #10 Die Die Die #9 Spawn #306 Bitter Root #7 Hardcore Reloaded #4 (of 5) Oblivion Song Vol. -

Exploring Identity in Nnedi Okorafor's Nigerian-American Speculative

Hybrid Identities and Reversed Stereotypes: Exploring Identity in Nnedi Okorafor’s Nigerian-American Speculative Fiction Catharina Anna (Tineke) Dijkstra s1021834 Supervisor: Dr. Daniela Merolla Second reader: Dr. J. C. (Johanna) Kardux Master Thesis ResMA Literary Studies Leiden University - Humanities Academic year 2014-2015 2 Table of contents Introduction 5 Theoretical Framework 5 Belonging 8 Stereotyping 13 Speculative Fiction 16 Chapter 1: Zahrah the Windseeker 21 Identity 23 Belonging 25 Stereotyping 29 Conclusion 35 Chapter 2: Who Fears Death 38 Identity 41 Belonging 44 Stereotyping 48 Conclusion 52 Chapter 3: Akata Witch 54 Identity 55 Belonging 59 Stereotyping 61 3 Conclusion 63 Chapter 4: Lagoon 65 Identity 67 Belonging 70 Stereotyping 72 Conclusion 75 Conclusion 77 Works Cited 81 4 Introduction The main concern of this study is to examine the notion of identity, specifically African American1 identity, through the analysis of speculative fiction. A project like this is too extensive to fully explore in the scope of a MA thesis. Therefore I choose to focus on two subthemes, namely belonging and stereotyping, which make up at least a considerable part of the debates considering diasporic identity. In the sections on belonging, I will explore how the case studies respond to and position themselves within the discussion by Homi K. Bhabha, Stuart Hall and Paul Gilroy on the double nature or hybridity of diasporic identity which started with W.E.B. Du Bois’ concept of ‘double consciousness’. In the sections on stereotyping, I examine how the case studies treat stereotypes and possibly try to reverse them. To explore this, I use theory by Stuart Hall on representation and Mineke Schipper’s Imagining Insiders: Africa and the Question of Belonging (1999). -

Miles Morales Jason Reynolds

Miles Morales Jason Reynolds GENRE: Action/Adventure or Fantasy - Superheroes BOOK SUMMARY Sixteen year old Miles Morales is from the Brooklyn projects; but under the surface, he’s not your normal teenager. Yes--he is in and out of trouble in school, has trouble talking to girls, and even rebels against his parents; but he is also Spider-Man which means he fights crime on the streets, slings a mean web, and can go into “camo” mode to hide. His troubles are mounting as Miles struggles with being biracial, his family's past, and a mean school administrator who also has secrets. Miles must decide to continue his superhero ways or walk away from the crime fighting life into something else. BOOK TALK Award winning author Jason Reynolds spins a new web in the Spider-Man saga with Miles Morales. Miles has the same Spidey senses and web slinging abilities that you are familiar with. However, this superhero is struggling with his racial identity, a crush on a classmate, and his role as a crime fighter, not to mention his recurring dreams about a white cat. It’s when his troubled past collides with the trouble he’s facing with school administration that Miles must make a decision. Will he walk away from the crime fighting life and be a normal teenager, or will he accept the fact that “with great power, comes great responsibility.” LINKS TO HELPFUL WEBSITES ● Official Book Trailer: https://youtu.be/XpEqN8yDW8s ● Author: https://www.jasonwritesbooks.com/ ● Other: https://youtu.be/BjHHrSbThGE Jason Reynolds discussing Miles Morales at a bookstore event ● TeachingBooks.net through INSPIRE: www.teachingbooks.net/ql3fkbn MAKERSPACE ACTIVITY Makerspace - Create spiderwebs * with yarn - https://www.wikihow.com/Make-a-Spider-Web * webshooter with popsicle sticks - https://youtu.be/rETLbz9LhTQ DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. -

The Muppets Take the Mcu

THE MUPPETS TAKE THE MCU by Nathan Alderman 100% unauthorized. Written for fun, not money. Please don't sue. 1. THE MUPPET STUDIOS LOGO A parody of Marvel Studios' intro. As the fanfare -- whistled, as if by Walter -- crescendos, we hear STATLER (V.O.) Well, we can go home now. WALDORF (V.O.) But the movie's just starting! STATLER (V.O.) Yeah, but we've already seen the best part! WALDORF (V.O.) I thought the best part was the end credits! They CHORTLE as the credits FADE TO BLACK A familiar voice -- one we've heard many times before, and will hear again later in the movie... MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) And lo, there came a day like no other, when the unlikeliest of heroes united to face a challenge greater than they could possibly imagine... STATLER (V.O.) Being entertaining? WALDORF (V.O.) Keeping us awake? MR. EXCELSIOR (V.O.) Look, do you guys mind? I'm foreshadowing here. Ahem. Greater than they could possibly imagine... CUT TO: 2. THE MUPPET SHOW COMIC BOOK By Roger Langridge. WALTER reads it, whistling the Marvel Studios theme to himself, until KERMIT All right, is everybody ready for the big pitch meeting? INT. MUPPET STUDIOS The shout startles Walter, who tips over backwards in his chair out of frame, revealing KERMIT THE FROG, emerging from his office into the central space of Muppet Studios. The offices are dated, a little shabby, but they've been thoroughly Muppetized into a wacky, cozy, creative space. SCOOTER appears at Kermit's side, and we follow them through the office. -

2012 Maverick Graphic Novel List

2012 Maverick Graphic Novel List Title Author/Artist ISBN Age GroupPublisher Astronaut Academy Zero Gravity Dave Roman 9781596436206 6-8 First Second Bake Sale Sara Varon 9781596434196 6-8 First Second Hereville: How Mirka Got her Sword Barry Deutsch 9780810984226 6-8 Amulet (Abrams) Last Unicorn Peter Beagle 9781600108518 6-8 IDW Lost and Found Shaun Tan 9780545229241 6-8 Scholastic Pirate Penguin Vs Ninja Chicken Ray Friesen 9781603090711 6-8 Top Shelf Possessions: Book One: Unclean Ray Fawkes 9781934964361 6-8 Oni Press Getaway Sidekicks Dan Santat 9780439298193 6-8 Scholastic Zita the SpaceGirl Ben Hatke 9781596434462 6-8 First Second 21: The Story of Roberto Clemente Wilfred Santiago 9781560978923 6-12 Fantagraphics Americus M. K. Reed and Jonathan 9781596437685 6-12 First Second David Hill Anya's Ghost Vera Brogol 9781596435520 6-12 First Second Avengers, Vol 1 Brian Michael Bendis 9780785145004 6-12 Marvel Bad Island Doug TenNapel 9780545314794 6-12 Graphix (Scholastic) Drawing From Memory Allen Say 9780545176866 6-12 Scholastic Evolution: the story of life on earth Jay Hosler, Kevin Cannon and 9780809043118 6-12 FSG (MacMillan) Zander Cannon Freshman: Tales of 9th Grade Corinne Mucha 9780981973364 6-12 Zest Books Obsessions, Revelations, and Other Nonsense I am Here! Ema T'yama 9780345522436 6-12 Random House Laddertop v. 1 Orson Scott Card, Emily Janice 9780765324603 6-12 Tor/Seven Seas Card with Zina Card ; illustrated by Honoel A. Ibardolaza 2012 Maverick Graphic Novel List Title Author/Artist ISBN Age GroupPublisher Last Dragon