"Framley Parsonage" and "Tooth and Claw"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men, Women, and Property in Trollope's Novels Janette Rutterford

Accounting Historians Journal Volume 33 Article 9 Issue 2 December 2006 2006 Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Janette Rutterford Josephine Maltby Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Rutterford, Janette and Maltby, Josephine (2006) "Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels," Accounting Historians Journal: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_journal/vol33/iss2/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Accounting Historians Journal by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rutterford and Maltby: Frank must marry money: Men, women, and property in Trollope's novels Accounting Historians Journal Vol. 33, No. 2 December 2006 pp. 169-199 Janette Rutterford OPEN UNIVERSITY INTERFACES and Josephine Maltby UNIVERSITY OF YORK FRANK MUST MARRY MONEY: MEN, WOMEN, AND PROPERTY IN TROLLOPE’S NOVELS Abstract: There is a continuing debate about the extent to which women in the 19th century were involved in economic life. The paper uses a reading of a number of novels by the English author Anthony Trollope to explore the impact of primogeniture, entail, and the mar- riage settlement on the relationship between men and women and the extent to which women were involved in the ownership, transmission, and management of property in England in the mid-19th century. INTRODUCTION A recent Accounting Historians Journal article by Kirkham and Loft [2001] highlighted the relevance for accounting history of Amanda Vickery’s study “The Gentleman’s Daughter.” Vickery [1993, pp. -

Framley Parsonage: the Chronicles of Barsetshire Pdf, Epub, Ebook

FRAMLEY PARSONAGE: THE CHRONICLES OF BARSETSHIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony Trollope,Katherine Mullin,Francis O'Gorman | 528 pages | 01 Dec 2014 | Oxford University Press | 9780199663156 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Framley Parsonage: The Chronicles of Barsetshire PDF Book It is funny too, because I remember the first time I read this series almost 20 years ago I did not appreciate the last four nearly so much at the first two. This first-ever bio… More. Start your review of Framley Parsonage Chronicles of Barsetshire 4. George Gissing was an English novelist, who wrote twenty-three novels between and I love the wit, variety and characterisation in the series and this wonderful book is no exception. There is no cholera, no yellow-fever, no small-pox, more contagious than debt. Troubles visit the Robarts in the form of two main plots: one financial, and one romantic. The other marriage is that of the outspoken heiress, Martha Dunstable, to Doctor Thorne , the eponymous hero of the preceding novel in the series. For all the basic and mundane humanity of its story, one gets flashes of steel, and darkness, behind all the Barsetshirian goodness. But this is not enough for Mark whose ambitions lie beyond the small parish of Framley. Lucy, much like Mary Thorne in Doctor Thorne acts precisely within appropriate boundaries, but also speaks her mind and her conduct does much towards securing her own happiness. Lucy's conduct and charity especially towards the family of poor priest Josiah Crawley weaken her ladyship's resolve. Audio MP3 on CD. On the romantic side there are also some more love stories with a lot less passion, starring some of our acquaintances. -

Gamblers and Gentlefolk: Money, Law and Status in Trollope's England

Gamblers and Gentlefolk: Money, Law and Status in Trollope’s England Nicola Lacey LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Papers 03/2016 London School of Economics and Political Science Law Department This paper can be downloaded without charge from LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Papers at: www.lse.ac.uk/collections/law/wps/wps.htm and the Social Sciences Research Network electronic library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2745378. © Nicola Lacey. Users may download and/or print one copy to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. Users may not engage in further distribution of this material or use it for any profit-making activities or any other form of commercial gain. Gamblers and Gentlefolk: Money, Law and Status in Trollope’s England Nicola Lacey* Abstract: This paper examines the range of very different conceptions of money and its legal and social significance in the novels of Anthony Trollope, considering what they can tell us about the rapidly changing economic, political and social world of mid Victorian England. It concentrates in particular on Orley Farm (1862) — the novel most directly concerned with law among Trollope’s formidable output — and The Way We Live Now (1875) — the novel most directly concerned with the use and abuse of money in the early world of financial capitalism. The paper sets the scene by sketching the main critiques of money in the history of the novel. Drawing on a range of literary examples, it notes that these critiques significantly predate the development of industrial let alone financial capitalism. Probably the deepest source of ambivalence about money in the novel has to do with ‘commodification’. -

Download Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868

Miss Mackenzie, Anthony Trollope, Chapman and Hall, 1868, , . DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1boZHoo Ayala's Angel (Sparklesoup Classics) , Anthony Trollope, Dec 5, 2004, , . Sparklesoup brings you Trollope's classic. This version is printable so you can mark up your copy and link to interesting facts and sites.. Orley Farm , Anthony Trollope, 1935, Fiction, 831 pages. This story deals with the imperfect workings of the legal system in the trial and acquittal of Lady Mason. Trollope wrote in his Autobiography that his friends considered this .... The Toilers of the Sea , Victor Hugo, 2000, Fiction, 511 pages. On the picturesque island of Guernsey in the English Channel, Gilliatt, a reclusive fisherman and dreamer, falls in love with the beautiful Deruchette and sets out to salvage .... The Way We Live Now Easyread Super Large 18pt Edition, Anthony Trollope, Dec 11, 2008, Family & Relationships, 460 pages. The Duke's Children , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The sixth and final novel in Trollope's Palliser series, this 1879 work begins after the unexpected death of Plantagenet Palliser's beloved wife, Lady Glencora. Though wracked .... He Knew He Was Right , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . Written in 1869 with a clear awareness of the time's tension over women's rights, He Knew He Was Right is primarily a story about Louis Trevelyan, a young, wealthy, educated .... Framley Parsonage , Anthony Trollope, Jan 1, 2004, Fiction, . The fourth work of Trollope's Chronicles of Barsetshire series, this novel primarily follows the young curate Mark Robarts, newly arrived in Framley thanks to the living .... Ralph the Heir , Anthony Trollope, 1871, Fiction, 434 pages. -

The Journal of The

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 96 ~ Autumn 2013 The Post Office Archives at Debden Pamela Marshall Barrell EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 96 ~ Autumn 2013 FEATURES rollope had the last word in the last issue on the subject of a late-starting spring/summer, but he might have been surprised 2 The Post Office Archives at Debden at the long hot days we have finally enjoyed. However, as this Pamela Marshall Barrell T Pamela Marshall Barrell gives a fascinating account of the Trollope fabulous summer finally draws to a close, preparations are under way Society’s recent visit to the Post Office Archives at Debden. for our 26th Annual Lecture on The Way We Live Now by Alex Preston, which will take place on 31st October at the National Liberal Club. It 10 How Well Did Trollope Know Salisbury? Peter Blacklock will be preceeded by the AGM and followed by drinks and supper. Do Peter Blacklock examines how a new book, The Bishop’s Palace at book your places as soon as possible. Salisbury, sheds new light on Trollope’s acquaintance with the city and As ever there are housekeeping notices. In order to keep you the Bishop’s Palace. up to date with last-minute events, we would like the ability to send you regular emails. If you would like us to do so, and have not 20 Framley Parsonage Sir Robin Williams already given us your email address, then do please send it to Sir Robin Williams explores the plot, characters and themes in the fourth [email protected]. -

Millais's Illustrations: Fuel for Trollope's Writing

MILLAIS’S ILLUSTRATIONS: FUEL FOR TROLLOPE’S WRITING Ileana Marin During the 1860s John Everett Millais provided 86 illustrations and two frontispieces for four novels by Anthony Trollope: Framley Parsonage (1861), Orley Farm (1862), The Small House at Allington (1864), and Phineas Finn (1869). The fruitful collaboration between Millais and Trollope was initiated by George Smith, the publisher of Cornhill Magazine , who believed that a successful magazine should combine quality illustrations with good literature. Smith thus invited Millais to illustrate Trollope’s Framley Parsonage , starting with the third installment of the novel (the first two were already out). Trollope was so excited about the news that he did not wait to write a formal letter of thanks to his publisher, but rather put a note directly on the proofs of the current installment: “Should I live to see my story illustrated by Millais, no body will be able to hold me” (Trollope, Letters 56). Another factor that might have helped Smith secure Millais’s collaboration was through the reader for the press, William Smith Williams, who was an old acquaintance of Millais from 1849, when the young painter was a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. 1 With the increasing success of Millais and the popularity of Trollope, it is no coincidence that these four novels were the most successful in the writer’s career. John Hall explains Trollope’s success by the fact that he gave Millais an “undeniable authority” and because the publishers integrated the plates in the text (2). For ten years, Trollope and his readers benefitted from Millais’s partnership, as did Trollope’s later illustrators, who borrowed postures and gestures from Millais’s sets of illustrations in order to maintain the Trollope brand. -

Anthony Trollope*S Literary Reputation;

ANTHONY TROLLOPE*S LITERARY REPUTATION; ITS DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY by ELLA KATHLEEN GRANT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for. the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of British Columbia, October, 1950. This essay attempts to trace the course of Anthony Trollope's literary reputation; to suggest some explan• ations for the various spurts and sudden declines of his popularity among readers and esteem among critics; and to prove that his mid-twentieth century position is not a just one. Drawing largely on Trollope's Autobiography, contemp• orary reviews and essays on his work, and references to it in letters and memoirs, the first chapter describes Trollope's writing career, showing him rising to popu• larity in the late fifties and early sixties as a favour• ite among readers tired of sensational fiction, becoming a byword for commonplace mediocrity in the seventies, and finally, two years before his death, regaining much of his former eminence among older readers and conservative critics. Throughout the chapter a distinction is drawn between the two worlds with which Trollope deals, Barset- shire and materialist society, and the peculiarly dual nature of his work is emphasized. Chapter II is largely concerned with the vicissitudes that Trollope's reputation has encountered since the post• humous publication of his autobiography. During the de• cade following his death he is shown as an object of comp• lete contempt to the Art for Art's Sake school, finally rescued around the turn of the century by critics reacting against the ideals of his detractors. -

A VISIT to BARSET the Barsetshire Novels of Anthony Trollope Aideen

93 A VISIT TO BARSET The Barsetshire Novels of Anthony Trollope Aideen E. Brody バー セ ッ トへ の 訪 問 アン トニー ・トロロップのバーセットシャーについての小説 エィ デ ィ ー ン ・ ブ ロ ー デ ィ 19世 紀 の 英 国 作 家 、 ア ン トニ ー ・ ト ロ ロ ッ プ は 架 空 の 州 、 イ ギ リ ス の バ ー セ ッ トシ ャ ー の ・ 人 々 の 生 活 を 描 い た6つ の 小 説 の 作 者 と し て 最:も知 ら れ て い る 。 本 論 文 で は 、 そ の6つ の 小 説 、 そ の 背 景 、 そ し て トロ ロ ッ プ 作 品 の 特 長 に つ い て 語 る。 Although Anthony Trollope was a prolific writer, he is today best remembered for his six books about life in Barsetshire , the fictitious West Country county with its principal town of Barchester which existed so vividly in Trollope's imagination. The novels were The Warden (written in 1855), Barchester Towers (1857), Doctor Thorne (1858), Framley Parsonage (1861), The Small House at Allington (1864) and The Last Chronicle of Barset (1867). Such is Trollope's power of description, both of people and places, that the reader becomes totally caught up in the life of the Barsetshire community, and the title of the final book comes to sound ominous, tolling the knell of parting pleasure. The last chronicle. Oh, no ! Neatly wrapped up and tied together though the series may be, we still want more. The Life of Anthony Trollope Born in London in 1815, Trollope's early life was marked by what might be a peculiarly English defect : coming from a `good' family, educated and titled, (Anthony Trollope's great-great grandson, Sir Anthony Trollope, is the current holder of the title), yet also a financially very embarrassed family, the father still thought it 94 Bul. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

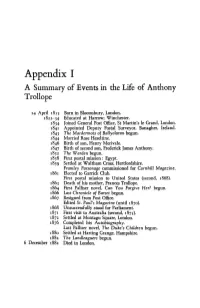

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

Anthony Trollope Framley Parsonage

ANTHONY TROLLOPE FRAMLEY PARSONAGE All rights reserved Non commercial use permitted Framley Parsonage by Anthony Trollope TABLE OF CONTENTS I 'OMNES OMNIA BONA DICERE' II THE FRAMLEY SET, AND THE CHALDICOTE SET III CHALDICOTES IV A MATTER OF CONSCIENCE V AMANTIUM IRAE AMORES INTEGRATIO VI MR HAROLD SMITH'S LECTURE VII SUNDAY MORNING VIII GATHERUM CASTLE IX THE VICAR'S RETURN X LUCY ROBARTS XI GRISELDA GRANTLY XII THE LITTLE BILL XIII DELICATE HINTS XIV MR CRAWLEY OF HOGGLESTOCK XV LADY LUFTON'S AMBASSADOR XVI MRS PODGERS' BABY XVII MRS PROUDIE'S CONVERSATSIONE XVIII THE NEW MINISTER'S PATRONAGE XIX MONEY DEALING XX HAROLD SMITH IN CABINET XXI WHY PUCK THE PONY WAS BEATEN XXII HOGGLESTOCK PARSONAGE XXIII THE TRIUMPH OF THE GIANTS XXIV MAGNA EST VERITAS XXV NON-IMPULSIVE XXVI IMPULSIVE XXVII SOUTH AUDLEY STREET XXVIII DR THORNE XXIX MISS DUNSTABLE AT HOME XXX THE GRANTLY TRIUMPH XXX1 SALMON FISHING IN NORWAY XXXII THE GOAT AND THE COMPASSES XXXIII CONSOLATION XXXIV LADY LUFTON IS TAKEN BY SURPRISE XXXV THE STORY OF KING COPHETUA XXXVI KIDNAPPING AT HOGGLESTOCK XXXVII MR SOWERBY WITHOUT COMPANY XXXVIII IS THERE CAUSE OR JUST IMPEDIMENT? XXXIX HOW TO WRITE A LOVE LETTER XL INTERNECINE XLI DON QUIXOTE XLII TOUCHING PITCH XLIII IS SHE NOT INSIGNIFICANT? XLIV THE PHILISTINES AT THE PARSONAGE XLV PALACE BLESSINGS XLVI LADY LUFTON'S REQUEST XLVII NEMESIS XLVIII HOW THEY WERE ALL MARRIED, HAD TWO CHILDREN, AND LIVED HAPPILY EVER AFTER CHAPTER I 'OMNES OMNIA BONA DICERE' When young Mark Robarts was leaving college, his father might well declare that all men began to say all good things to him, and to extol his fortune in that he had a son blessed with an excellent disposition. -

Framley Parsonage

Framley Parsonage Anthony Trollope Framley Parsonage Table of Contents Framley Parsonage....................................................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. 'OMNES OMNIA BONA DICERE'.......................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. THE FRAMLEY SET, AND THE CHALDICOTES SET...................................................7 CHAPTER III. CHALDICOTES.................................................................................................................13 CHAPTER IV. A MATTER OF CONSCIENCE........................................................................................20 CHAPTER V. AMANTIUM IRAE AMORIS INTERGRATIO................................................................25 CHAPTER VI. MR HAROLD SMITH'S LECTURE.................................................................................33 CHAPTER VII. SUNDAY MORNING......................................................................................................39 CHAPTER VIII. GATHERUM CASTLE...................................................................................................43 CHAPTER IX. THE VICAR'S RETURN...................................................................................................53 CHAPTER X. LUCY ROBARTS...............................................................................................................58