Create by Pagemanager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School Bus Services in the Oldham Area

School Bus Services in the Oldham Area September 2020 to July 2021 Journeys in this leaflet operate on schooldays only, unless otherwise stated. Services are listed alphabetically under school names. - 1 - 18/09/2020 12:30:00 An introduction to School buses and concessionary fares for students in Greater Manchester Passengers can pay a fare to the driver for each journey shown on this timetable. However, students will need to show an IGO pass to travel at the concessionary (reduced) fare. If students do not have an IGO pass, they will have to pay a higher fare. Most of the journeys shown in this timetable are funded by Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM). The majority of TfGM funded services charge a standard fare and also offer daily return tickets. In some cases, the return ticket can also be used for travel on other journeys which serve similar areas – even if it is provided by a different operator. On most services, students can also buy a weekly scholar’s ticket, which costs £7.60. These are ONLY valid on schooldays on school buses and are available from the bus driver on all services where they are applicable. To help the driver, please try to have the correct fare when buying your ticket. Carnet ticket (10 single trips) £10 – available to buy on the bus or at a TfGM Travel shop. A summary of fares and ticketing information on all school services included in this timetable can be found at https://www.tfgm.com/tickets-and-passes/bus-school-bus-services There are also a small number of TfGM funded services where the operator sets the fares. -

Ward Profile 2018: Werneth

Ward Profile 2018: Werneth Produced by Oldham Council’s Business Intelligence Service Population 13,497 50.3% 49.7% 2016 Population Male Population Female Population 11.1% Increase since 2011 Oldham Male Population; 49.3% Oldham Female Population; 50.7% Within the Oldham borough Werneth has the fourth largest ward Ethnic Composition Source: ONS Census 2011 population and this has increased by 11.1% in five years. % Other % White % Pakistani % Bangladeshi The largest gain is the age bracket for children aged 0-15 years old, non-white 2011 (2001) 2011 (2001) 2011 (2001) where there was a 13.2% gain. The majority of the population 2011 (2001) (69.2%) is under 40 years old, and the population pyramid shows a Werneth 23.4 (43.2) 48.6 (38.2) 17.8 (11.6) 10.3 (7.1) clear towards younger people which will feed through to further population rises. Oldham 79.5 (87.1) 9.1 (5.9) 6.6 (4.1) 4.9 (2.9) In a diverse ward, nearly one in two (48.6%) ward residents are of England 85.4 (90.9) 2.1 (1.4) 0.8 (0.6) 11.7 (7.1) Pakistani heritage. Economy and Income £19,994 42.5% 21.4% Median Household Income Employment Rate Out of Work Benefit Claimants Oldham average; £24,652 Oldham average; 58.2% Oldham average; 17.7% Werneth has very low employment figures and high Out of Work Economic Status Benefits being issued. The level of employment suggests a high Aged 16-74 years old; Source ONS Census 2011 Werneth Oldham England level of economic inactivity. -

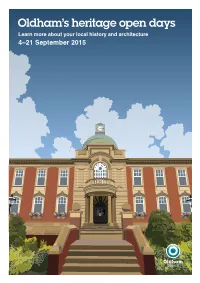

Oldham's Heritage Open Days

Oldham’s heritage open days Learn more about your local history and architecture 4–21 September 2015 12pp Heritage OD leaflet 2015 .indd 1 04/08/2015 14:53 Welcome to Oldham Council’s Heritage Open Days, your opportunity to find out more about the history and heritage of your area. From talks to walks there’s plenty to discover, whether you’re interested in architecture or heritage or just curious about the history around you. 6-21 September Every Monday and Wednesday A Tale of the Dardanelles Family History Advice A display telling the story of the 2pm-4pm: Needing help with family Oldham Territorials at Gallipoli. history? Expert advice available. Oldham Local Studies and Archives, Oldham Local Studies and Archives, 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. 84 Union Street, Oldham OL1 1DN. Mon and Thurs 10am-7pm; Tues Disabled access; toilets 10am-2pm; Wed and Fri 10am-5pm; Sat 10am-4pm. 4-6 September Disabled access; toilets Flower festival 12noon-5pm: Holy Trinity Church, Oldham Town Centre Shaw. Commemorating the 500th Past and Present anniversary of the site being a place Photographs comparing Oldham of worship. Church Road, Shaw, Town Centre of today with that of the Oldham, OL2 7SL. Disabled access; past. Oldham Town Centre Office, toilets; parking; refreshments 12 Albion Street, Oldham, OL1 3BG. Mon-Fri 10am-5pm. Disabled access Saturday 5 September Growing Up in Old St Mary’s Holy Trinity Church, Bardsley Display of photographs, books 9am-12noon: Find out more about and memories of the making of the the church and its community; documentary ‘Just Like Coronation includes tours of clock tower. -

Oswestry Borough Council

Oldham Local Development Framework Open Space Study Steps One and Two September 2006 Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council PPG 17 Local Needs Assessment and Audit A Final Report by PMP September 2006 OLDHAM DISTRICT COUNCIL OPEN SPACE, SPORT AND RECREATION STUDY A FINAL REPORT BY PMP SEPTEMBER 2006 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary 1. Introduction and Background 1 2. Undertaking the Study – PPG17 5 3. Strategic Context 19 4. Consultations 34 5. Parks and Gardens 46 6. Natural and Semi-Natural Open Space 58 7. Amenity Greenspace 68 8. Provision for Children and Young People 78 9. Outdoor Sports Facilities 90 10. Allotments and Community Gardens 103 11. Cemeteries and Churchyards 111 12. Green Corridors 116 13. Civic Spaces 120 14. The Way Forward 125 APPENDICES Appendix A Benefits of open space Appendix B Open space typology - definitions Appendix C Surveys Appendix D Definitions Appendix E List of Sites Appendix F National Strategic Context Appendix G Site Assessment Matrix Appendix H Quantity standards Appendix I Quality standards Appendix J Accessibility standards Appendix K Quality Benchmarking EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background i. PMP were appointed to undertake a local needs assessment and audit of open space, sport and recreation facilities across the Borough of Oldham in accordance with the requirements of the latest Planning Policy Guidance Note 17 (Planning for Open Space Sport and Recreation, July 2002) and its Companion Guide (September 2002). ii. The Council commissioned PMP to undertake steps one and two of the five-step process outlined in the Companion Guide (and below). Recommendations for local provision standards (step 3) have also been provided. -

Infrastructure Study 1 List of Abbreviations

1 List of Abbreviations 2 2 Executive Summary 4 3 Introduction 7 Why we have done the Study 7 How we have done the Study 10 4 Physical Infrastructure 16 Travel Routes 16 Street Lighting 28 Utilities 28 Flood Prevention 35 Waste 36 5 Social Infrastructure 41 Access to Services 41 Education 41 Housing 54 Health 57 Community 61 Emergency Facilities 68 Religious Facilities 71 Cultural Facilities 75 6 Green Infrastructure 78 Open Spaces 78 Natural Environment 86 Waterways 94 7 Infrastructure planning delivery 98 8 Glossary of Terms 109 9 Appendix 1: Infrastructure planning updates 111 Oldham LDF: Infrastructure Study 1 List of Abbreviations This is a list of the most commonly used abbreviations in this report. BW Boroughwide BSF Building Schools for the Future CG Central Government DCLG Department for Communities and Local Government DfE Department for Education DfT Department for Transport DPD Development Plan Document EA Environment Agency FC Forestry Commission GM Greater Manchester GMFM Greater Manchester Forecasting Model GMTU Greater Manchester Transport Unit GMWDA Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority HMR Housing Market Renewal LAA Local Area Agreement LIFT Local Improvement Finance Trust LDF Local Development Framework LTP Local Transport Plan MCC Manchester City Council MWMS Municipal Waste Management Strategy NDC New Deal for Communities OC Oldham Council PCP Primary Capital Programme PCT Primary Care Trust PFI Private Finance Initiative PPG Planning Policy Guidance note 2 Oldham LDF: Infrastructure Study PPS Planning Policy Statement PRoW Public Rights of Way RFA Regional Funding Allocation SAC Special Area of Conservation SBI Site of Biological Importance SCS Sustainable Community Strategy SFRA Strategic Flood Risk Assessment SPA Special Protection Area SPD Supplementary Planning Document SSSI Site of Special Scientific Interest UP Unity Partnership Oldham LDF: Infrastructure Study 3 2 Executive Summary 2.1 Critically, infrastructure will not hinder the delivery of the Local Development Framework. -

Uk Regional Development Programme 1986-90

EUROPEAN REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT FUND UK REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1986-90 Section 7E: England — South Yorkshire Section 7F: England — Workington Section 7G: England — Greater Manchester Section 7H: England — Greater Merseyside lUlaUmiãl· I U If ΦΟ DOCUMENT DOCUMENTI CUMENT DOCUMENTO DOK1 ¡NT ΕΓΓΡΑΦΟ DOCUMENT DI JMENTO DOCUMENT UUCUM TU ηυκυΜΕΝΤΕΓΓΡΑΦΟηΐ (MENT DOCUMENTO OUCUMI MHB ΡΑΦΟΟΟΟΟΜΕΜ I tvivl COMMISSION POOGIIIÌEN^DOG OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES ΝΤΕΓΓΡΑΦ( uranFrinii nni-iiupuiiiAnAni This document has been prepared for use within the Commission. It does not necessarily represent the Commission's official position. Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987 Vol.3 : ISBN 92-825-7194-7 Vol. 1-7: ISBN 92-825-7199-8 Catalogue number: CB-98-87-00J-EN-C © ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels · Luxembourg, 1987 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium Commission of the European Communities European Regional Development Fund UK RE6I0NAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1986-90 Section 7E: EngLand - South Yorkshire Section 7F: EngLand - Workington Section 7G: EngLand - Greater Manchester Section 7H: EngLand - Greater Merseyside Document This document has been prepared for use within the Commission. It does not necessarily represent the Commission's official position. Copyright ECSC-EEC-EAEC, Brussels - Luxembourg, 1987 Reproduction is authorized, except for commercial purposes, provided the source is acknowledged. / L European Regional Development Fund UK REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1986-90 Section 7E: England - South Yorkshire d UCJ [ \j \ 1' UK REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1986-90 CONTENTS The Programme consists of detailed information on regional or sub-regional areas (Sections 7 to 10) preceded by general information on the United Kingdom (Sections 1 to 6). -

Create by Pagemanager

ATHENE A Journal of NATURAL HISTORY and Microscopy February, 1965 No, 6 Published by The Oldham Microscopical Society and Field Club UTTLE OWL, ATHENE NOCTUA VIDALII Editor : L. N. KIDD, F.L.S., F.R.E.S. Assistant Editor : R. J. STANTON, M.A. Price 2/6 OLDHAM MICROSCOPICAL SOCIETY AND FIELD CLUB ESTABLISHED 1864 Headquarters: I Werneth Park Study Centre and Natural History Museum, Oldham President: A. HUMPHREYS, ESQ. Meetings held weekly at the Society's Headquarters on Monday evenings at 7-30 p.m. Outdoor Meetings also held during summer months, usually on Saturday. Members are entitled to borrow books from the Society's Library and to make use of the instruments. Annual Subscription 10/- Junior Members (under 18) 5/- Further particulars and copy of the current syllabus obtainable from: — The Hon. Secretary, Mr. W. F. EDWARDS, 31, Mersey Road, Failsworth Further copies of ' Athene ' can be obtained from : — The Publications Secretary, Miss A. C. CHA.DDERTON, 78, Oldham Road, Grasscroft, Nr. Oldham, or from The Society's Headquarters Orders should bo accompanied by postal order or cheque for 2/6, plus 4d. postage. CENTENARY BY ALBERT HUMPHREYS To mark the hundredth year of our Society, which we believe is the second oldest Microscopical Society in Great Britain, it was resolved firstly, to have a Summer ramble over the same ground as the first ramble mentioned in our records, which was in July 1867 and secondly, to end the season with a dinner. Both these events were a complete success. We are proud to record that the Summer rambles whose object is to collect specimens and make records of the fauna and flora, have continued every year for nearly a century. -

And Heritage Open Days 9 September – 5 October 2019

Oldham Histories Festival and heritage open days 9 September – 5 October 2019 1 Heritage OD leaflet 2019.indd 1 16/08/2019 11:28 Oldham Council’s Histories Festival and Heritage Open Days, this is your chance to find out more about the people, places, buildings and stories in your area. From talks to walks there’s plenty to discover, whether you’re interested in architecture or heritage or just curious about the history around you. All events are free, and there’s no need to book, unless it is otherwise stated. Cover image: Saddleworth Gone But Not Forgotten (page 7) Key: disabled access parking refreshments toilets Mon 9 – Fri 20 September Mon 9 – Sat 21 September (weekdays only) From Waterloo to Peterloo Mayor’s Parlour and Civic An exhibition exploring what life Silverware Tour was like in 1819 in Oldham around Take a tour of the Mayor’s Parlour the time of the Peterloo Massacre. and view the Trust Silver of the 10th Includes a selection of images from a Battalion Manchester Regiment. new graphic novel about Peterloo. Gallery Oldham, Civic Silverware Tour Greaves Street, Oldham OL1 1AL Open: Mon-Sat, 10am-5pm From Waterloo to Peterloo Central to this display are the silver drums and bugles purchased by the Ladies of Oldham in 1924 as a memorial to those who had fallen in the Great War. Civic Centre, West Street, Oldham OL1 1UJ T: 0161 770 4012 for details 2 Heritage OD leaflet 2019.indd 2 16/08/2019 11:28 Mon 9 Sept – Sat 5 Oct taken in 1876 by Squire Knott. -

Focus on Lifelong Learning Oldham Lifelong Learning Service Part Time Courses for Adults 2019/20

Focus on Lifelong Learning Oldham Lifelong Learning Service Part time courses for adults 2019/20 Lots of FREE provision. Find out if you qualify. www.oldham.gov.uk/lifelong E: [email protected] T: 0800 525 956 F: oldhamlifelonglearning 1 Welcome to Oldham Lifelong Learning Enrolment: How to join a course This booklet gives you information about the subjects If you would like to enrol on a course or require additional we offer and some of the support services and information you can: facilities we provide. Contact our Freephone number on T: 0800 525 956 We can help you gain the skills you need to get a or E: [email protected] job, move on in your career or perhaps start your You can also access our online course finder at: own business. www.oldham.gov.uk/lifelong where you have access to our You can also develop new skills through our course information sheets. community and family learning programmes. Enrolment for courses which need We will support you at every step of your learning a skills check or interview journey, whatever you choose to study. Jon Bloor Head of Service For some courses, mainly those with a qualification you need to meet Our commitment to our learners and the high quality a tutor for an informal interview or skills check before you can enrol. of delivery were recognised in Ofsted’s ‘Outstanding’ judgement in November 2015 and more recently in May 2019 when we were To arrange an appointment for your interview/skills check please ring reassessed to the Matrix Standard of Quality in information, advice one of the numbers listed below: and guidance. -

What's Doing Issue

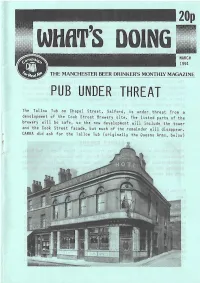

20p ,, WHATS DOING MARCH 1991 CY THE MANCHESTER BEER DRINKER’S MONTHLY MAGAZINE PUB U N D E R THREAT T h e Tallow T u b on Chapel Street, Salford, is under threat from a development o f t h e Cock Street Brewery s i t e . The listed parts of t h e brewery will be safe, s o the new development will include the tower a n d t h e Cook Street facade, b u t m u c h of the remainder will disappear. CAMRA did a s k f o r t h e T a l l o w T u b (originally t h e Queens Arms, below) itself to be listed but unfortunately the inspector looked only at the exterior which had been progressively bastardised by Whitbread during their ownership. The building today, with its bricked-up doors, canopies and inappropriate signage, is somewhat unprepossessing. Had the inspector ventured inside, however, he would have observed that the pub retains its original floor plan and that the unspoiled interior features are unique in Salford — impressive tiling throughout and a glass screen between the vault and the rear room. It is these interior features (rather than the tatty exterior) which could be restored at minimal cost, which make the pub worth saving. The Tallow Tub occupies a tiny area of the development site and would, because of its main road position, probably be replaced by grass and railings. It dates back to 1802, is a building of character and could form a focal point for the new development in an area which will, given current proposals, be underpubbed. -

396 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

396 bus time schedule & line map 396 Ashton - Middleton Via Limehurst Farm, Fitton Hill View In Website Mode The 396 bus line (Ashton - Middleton Via Limehurst Farm, Fitton Hill) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Ashton-Under-Lyne: 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM (2) Copster Hill: 5:42 PM (3) Middleton: 6:38 AM - 4:42 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 396 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 396 bus arriving. Direction: Ashton-Under-Lyne 396 bus Time Schedule 70 stops Ashton-Under-Lyne Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM Middleton Bus Station, Middleton Tuesday 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM Townley Street, Middleton Taylor Street, Manchester Wednesday 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM Vale Street, Middleton Thursday 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM Vale Street, Manchester Friday 6:49 AM - 5:58 PM Hare & Hounds, Middleton Saturday 8:18 AM - 4:49 PM Tudor Street, Manchester Kenyon Lane, John Lee Fold Norman Close, Manchester 396 bus Info Vitafoam, Middleton Direction: Ashton-Under-Lyne Whitby Street, Manchester Stops: 70 Trip Duration: 60 min Baytree Lane, Mills Hill Line Summary: Middleton Bus Station, Middleton, 528 Oldham Road, Manchester Townley Street, Middleton, Vale Street, Middleton, Hare & Hounds, Middleton, Kenyon Lane, John Lee Mills Hill Station, Mills Hill Fold, Vitafoam, Middleton, Baytree Lane, Mills Hill, Mills Hill Station, Mills Hill, Baptist Church, Mills Hill, Baptist Church, Mills Hill Malta Mill, Mills Hill, Laurel Avenue, Mills Hill, Firwood Park, Mills Hill, Oak Bank, Mills -

Oak Mill Chase Chadderton, Oldham

Oak Mill Chase Chadderton, Oldham Welcome to Oak Mill Chase – a superb new development of spacious family homes located in Chadderton, near Oldham’s vibrant town centre. Built by award-winning house builder, Countryside Properties, four stunning 2 bedroom homes have been set aside for shared ownership sale, through Plumlife, the government-backed affordable homes specialist. About Oak Mill Chase Oldham OL9 7JE Each property features light and spacious living spaces, fab contemporary fi tted kitchens with stainless steel oven and hob extractor, crisp modern bathroom, secure off-road parking and private garden at the rear. The homes are also highly eco-effi cient, benefi ting from top-notch insulation and energy saving boilers, as well as high-spec double-glazing and PV (Solar) roof panels, making them very inexpensive to heat and maintain. About the neighbourhood Oak Mill Chase is located in the heart of Chadderton, a residential area situated just two miles outside Oldham town centre to the north, and only six miles from central Manchester to the south, accessed easily via the A62. Oldham itself enjoys a cosmopolitan and vibrant mix of high street shopping and leisure facilities, and also boasts a charming ‘cultural quarter’ which includes the Oldham Coliseum Theatre and Oldham Gallery. Close by to the development are a number of fantastic green spaces and parks, including Werneth Park, with its Octagonal Music Rooms, central gardens, tennis courts, football pitch, woodland trail and play area. Public transport links are excellent, the development being just 2 miles from Oldham train station, and a mile from the M60.