Assessing How Terrain Representations and Scale Affect the Accuracy of Distance Estimates Kristian Mueller University of New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

60 Cartographic Perspectives Number 57, Spring 2007 Ing Templates of Old Style Map Production

60 cartographic perspectives Number 57, Spring 2007 ing templates of old style map production. All publish- Thoughts on Two New Map Design Texts ing is commercial; Guilford and Oxford presses no less than ESRI’s produce books in hopes of making money. Designing Better Maps : A Guide for GIS Users That ESRI Press is part of the greater software corpora- By Cynthia Brewer tion means it can afford to subsidize the scores of color ESRI Press, 2005. maps Brewer presents while Guilford Press was forced to limit severely the amount of color that Krygier and Making MAPS: A Visual Guide to Map Design for Wood could include in their book. Somebody is going GIS to pay; somebody hopes to make money. ESRI’s sup- By John Krygier and Dennis Wood port of Brewer’s project strikes me as appropriate and Guildford Press, 2005. responsible. Reviewed by George McCleary Conclusion University of Kansas I like these books. What I really like is having both on In 1938, when Erwin Raisz produced the first Ameri- my shelf. Rhetoric needs aesthetics if its argument is to can textbook in cartography, he pointed out [vii] that be carried forcefully. Aesthetics needs a point of view … when we look for literature on the science and art if the result is to be anything but vacuous. The map is of map making, we find that surprisingly little has argument. It is also image. Brewer holds the line as a been written. … Most of the American books … are craftsperson, the old tradition of the designer. Krygier written from the point of view of the practical drafts- and Wood open the door to a critique of the ideas pre- man. -

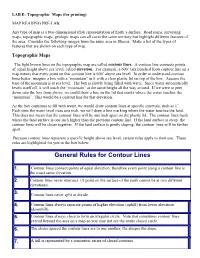

General Rules for Contour Lines

6/30/2015 EASC111LabEFor Printing LAB E: Topographic Maps (for printing) MAP READING PRELAB: Any type of map is a twodimensional (flat) representation of Earth’s surface. Road maps, surveying maps, topographic maps, geologic maps can all cover the same territory but highlight different features of the area. Consider the following images from the same area in Illinois. Make a list of the types of features that are shown on each type of map. Topographic Maps The light brown lines on the topographic map are called contour lines. A contour line connects points of equal height above sea level, called elevation. For example, a 600’ (six hundred foot) contour line on a map means that every point on that contour line is 600’ above sea level. In order to understand contour lines better, imagine a box with a “mountain” in it with a clear plastic lid on top of the box. Assume the base of the mountain is at sea level. The box is slowly being filled with water. Since water automatically levels itself off, it will touch the “mountain” at the same height all the way around. If we were to peer down into the box from above, we could draw a line on the lid that marks where the water touches the “mountain”. This would be a contour line for that elevation. As the box continues to fill with water, we would draw contour lines at specific intervals, such as 1”. Each time the water level rises one inch, we will draw a line marking where the water touches the land. -

Cartographic Design and Desktop Mapping: a Historic Perspective

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Cartographic design and desktop mapping: A historic perspective Thomas A. Marcotte The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Marcotte, Thomas A., "Cartographic design and desktop mapping: A historic perspective" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8444. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8444 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of iV fO N T A N A Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check ”Yes‘* or "No" and provide signarure Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date n / ^ _____________________ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. Cartographie Design and Desktop Mapping A Historic Perspective by Thomas A. Marcotte B.A. The University of Maine at Farmington, 1995 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2000 airperson Dean, Graduate School I \ " Date UMI Number: EP39245 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Framing Guidelines for Multi-Scale Map Design Using Databases at Multiple Resolutions

Framing Guidelines for Multi-Scale Map Design Using Databases at Multiple Resolutions Cynthia A. Brewer and Barbara P. Buttenfield ABSTRacT: This paper extends European research on generating cartographic base maps at multiple scales from a single detailed database. Similar to the European work, we emphasize reference maps. In contrast to the Europeans’ focus on data generalization, we emphasize changes to the map display, including symbol design or symbol modification. We also work from databases compiled at multiple resolutions rather than constructing all representations from a single high-resolution database. We report results demonstrating how symbol change combined with selection and elimination of subsets of features can produce maps through almost the entire range of map scales spanning 1:10,000 to 1:5,000,000. We demonstrate a method of establishing specific map display scales at which symbol modification should be imposed. We present a prototype decision tool called ScaleMaster that can guide multi-scale map design across a small or large range of data resolutions, display scales, and map purposes. Introduction • At what point(s) in a multi-scale progression will data geometry be modified to suit smaller scale presentation; and apmaking at scales between those • At what point(s) in a multi-scale progression that correspond to available database must new data compilations be introduced. resolutions can involve changes to From a data processing standpoint, symbol modi- Mthe display (such as symbol changes), changes to fication is often less intensive than geometry modi- feature geometry (data generalization), or both. fication, and thus changing symbols can reduce These modifications are referred to (respec- overall workloads for the map designer. -

Maps and Charts

Name:______________________________________ Maps and Charts Lab He had bought a large map representing the sea, without the least vestige of land And the crew were much pleased when they found it to be, a map they could all understand - Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark Map Projections: All maps and charts produce some degree of distortion when transferring the Earth's spherical surface to a flat piece of paper or computer screen. The ways that we deal with this distortion give us various types of map projections. Depending on the type of projection used, there may be distortion of distance, direction, shape and/or area. One type of projection may distort distances but correctly maintain directions, whereas another type may distort shape but maintain correct area. The type of information we need from a map determines which type of projection we might use. Below are two common projections among the many that exist. Can you tell what sort of distortion occurs with each projection? 1 Map Locations The latitude-longitude system is the standard system that we use to locate places on the Earth’s surface. The system uses a grid of intersecting east-west (latitude) and north-south (longitude) lines. Any point on Earth can be identified by the intersection of a line of latitude and a line of longitude. Lines of latitude: • also called “parallels” • equator = 0° latitude • increase N and S of the equator • range 0° to 90°N or 90°S Lines of longitude: • also called “meridians” • Prime Meridian = 0° longitude • increase E and W of the P.M. -

Spring 2013 Geovisualization and Analytical Cartography GEP

GEP 199 / GEP 660 Syllabus – Spring 2013 Geovisualization and Analytical Cartography GEP 360/ GEP 660 Spring 2013 Catalogue Students will utilize advanced Geographic Information Science (GISc) and Description: graphic design techniques in tandem with licensed and free software to produce maps and geovisualizations of complex spatial data with a focus on understanding cartographic conventions and principles of good cartographic design. Maps will be studied critically in terms of their production, interpretation, and relationship to space and place. Course Meets: Gillet Hall, Rm. 322 (GISc Lab), Tuesday 5:00 to 10:10 Instructor: Gretchen Culp Email: [email protected] Required Books: “GIS Cartography: A Guide to Effective Map Design” by Gretchen N. Peterson, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2009 “Mapping: A Critical Introduction to Cartography and GIS” by Jeremy W. Crampton, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010 Other Required Selected Readings (posted on course Google Docs page) from pertinent Readings cartography journals: (selected chapters The Cartographic Journal and papers): Cartographica Cartographic Perspectives Imago Mundi The International Journal for the History of Cartography Recommended GIS for the Urban Environment, by Juliana Maantay and John Zielger, 2006, Books: ESRI Press Cartography: Visualization of Geospatial Data, by Menno-Jan Kraak and Ferjan Ormeling, Prentice Hall Cartography: Thematic Map Design, 5th Edition, by Borden Dent, 1999, McGraw Hill Cartographers’ Toolkit, by Gretchen Peterson, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 2012 Course Learning Objectives After successfully completing this course, students should be able to: • Interpret maps and cartographic products produced in different eras, for different purposes, and by different cultures, and understand the context of maps and geographic representation in socio-economic and political structures. -

Download Download

Cartographic Perspectives Journal of the North American Cartographic Information Society Number 68, Winter 2011 Cartographic Perspectives Journal of the North American Cartographic Information Society Number 68, Winter 2011 IN THIS ISSUE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Patrick Kennelly 3 PEER-REVIEWED ARTICLES The Search for a Radical Cartography 7 Mark Denil A Typology of Operators for Maintaining Legible Map Designs at Multiple Scales 29 Robert E. Roth, Cynthia A. Brewer, & Michael S. Stryker CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS Top Ten Jewels of the Ort Library Map Collection 65 MaryJo A. Price TRAVEL LOG Travels with iPad Maps 75 Michael P. Peterson ON THE HORIZON Introducing “On the Horizon” 83 Andrew Woodruff REVIEWS Reviews 87 W. Wilson, Russell S. Kirby, Jörn Seemann, Julia Siemer VISUAL FIELDS Bogus Art Maps 93 Tim Wallace IN THE MARGINALIA Student Map Competitions 96 Daniel Huffman and Mathew Dooley Instructions to Authors 98 Cartographic Perspectives, Number 68, Winter 2011 | 1 Cartographic Perspectives EDITOR Journal of the Patrick Kennelly Department of Earth and North American Cartographic Environmental Science Information Society CW Post Campus of Long Island University 720 Northern Blvd. ©2011 NACIS ISSN 1048-9085 Brookville, NY 11548 [email protected] www.nacis.org ASSISTANT EDITORS EDITORIAL BOARD Laura McCormick Robert Roth Sarah Battersby XNR Productions University of Wisconsin-Madison University of South Carolina [email protected] [email protected] Cynthia Brewer The Pennsylvania State University Mathew Dooley SECTION EDITORS -

This Should Be a Circle Information Visualization

This should be a circle Information Visualization Jack van Wijk Eindhoven University of Technology Electronics & Automation June 2/3/4, 2015 Information Visualization • What is it? • Presentation • Perception • Interaction • Data Information Visualization • The use of computer-supported, interactive, visual representations of abstract data to amplify cognition (Card et al., 1999) Data Visualization User Why is my hard disk full? ? SequoiaView Van Wijk and Van de Wetering, 1999 Generalized treemaps • Idea: combine treemaps and business graphics • Many options Vliegen, Van Wijk, and Van der Linden, 2006 Visualization high school data Cum Laude by MagnaView Information Visualization • The use of computer-supported, interactive, visual representations of abstract data to amplify cognition (Card et al., 1999) Data Visualization User SequoiaView Van Wijk and Van de Wetering, 1999 Botanically inspired treevis What happens if we map abstract trees to botanical trees? Kleiberg et al., 2001 BotanicallyTreeView inspired treevis Kleiberg, Van de Wetering, van Wijk, 2001 Botanically inspired treevis Kleiberg, Van de Wetering, van Wijk, 2001 Visualization of vessel traffic Willems et al., 2009 Visualization of vessel traffic Willems et al., 2009 Information Visualization • The use of computer-supported, interactive, visual representations of abstract data to amplify cognition • (Card et al., 1999) Data Visualization User The human visual system http://eofdreams.com The human visual system http://vinceantonucci.com Translating data into pictures Position, -

Temporal Gisplay

Rui Rodrigo Garcia Alves Licenciado em Engenharia Informática Temporal Gisplay Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Engenharia Informática Orientador: João Carlos Gomes Moura Pires, Assistant Professor, NOVA University of Lisbon Co-orientador: Fernando Pedro Reino da Silva Birra, Assistant Professor, NOVA University of Lisbon Júri Presidente: Prof. Doutor Pedro Medeiros Arguente: Prof. Doutor Daniel Gonçalves Vogal: Prof. Doutor João Moura Pires Dezembro, 2017 Temporal Gisplay Copyright © Rui Rodrigo Garcia Alves, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa. A Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia e a Universidade NOVA de Lisboa têm o direito, perpétuo e sem limites geográficos, de arquivar e publicar esta dissertação através de exemplares impressos reproduzidos em papel ou de forma digital, ou por qualquer outro meio conhecido ou que venha a ser inventado, e de a divulgar através de repositórios científicos e de admitir a sua cópia e distribuição com objetivos educacionais ou de inves- tigação, não comerciais, desde que seja dado crédito ao autor e editor. Este documento foi gerado utilizando o processador (pdf)LATEX, com base no template “unlthesis” [1] desenvolvido no Dep. Informática da FCT-NOVA [2]. [1] https://github.com/joaomlourenco/unlthesis [2] http://www.di.fct.unl.pt Agradecimentos À Universidade Nova de Lisboa e à NOVA LINCS. Aos meus pais pelo apoio demonstrado, aos orientadores pela orientação e conhecimento partilhado e aos meus colegas pelo feedback construtivo. v Resumo Nos dias que correm devido à ubiquidade dos dispositivos que recolhem informa- ção, desde computadores a telemóveis, são produzidos uma grande quantidade de dados, sendo que estes dados têm a componente temporal e também espacial porque os disposi- tivos são móveis e têm eles próprios capacidade de recolha de localização. -

Cynthia Brewer GI Forum Keynote on Friday, July 10, 2020, 13:30 at Audimax "Systematizing Cartographic Design" Short B

Cynthia Brewer Cartographer, Professor, Head of Department of Geography, Penn State, USA GI_Forum Keynote on Friday, July 10, 2020, 13:30 at AudiMax Young Researchers’ Corner on Thursday, July 9, 16:30 – 18:00 at HS 413 "Systematizing Cartographic Design" Cindy presents an overview of varied projects from her years of research and consulting that build to understanding the change in cartographic design approaches—from single perfected displays to systematic interlinked decisions that produce map designs that function flexibly over varied landscapes, levels of data completeness, and map scale. She has worked on United States census atlases, mortality mapping, and topographic map series design. These projects led to ColorBrewer.org and establishing basic categories of map color schemes with Judy Olson. The importance of removing features by importance levels for design through scale was a core result of the ScaleMaster work she did U.S. Geological Survey collaborators working on topographic mapping. These approaches help others plan sound cartographic tools and make meaningful maps. They are explained for novice mapmakers and GIS users in her book Designing Better Maps (2016). Short bio Cindy Brewer, Professor of Geography, has been a member of the Pennsylvania State University faculty since 1994. She has been the head of the Department of Geography at Penn State for six years. Her research and teaching focus is cartographic design. Brewer’s research interests include cartographic communication and visualization, map design, color theory, atlas production, multi-scale mapping, and topographic map series. Prior to joining Penn State, Brewer was an assistant professor of geography at San Diego State University, and she earned her doctorate in geography with emphasis in cartography from Michigan State University in 1991. -

Topographic Maps Fields

Topographic Maps Fields • Field - any region of space that has some measurable value at every point. • Ex: temperature, air pressure, elevation, wind speed Isolines • Isolines- lines on a map that connect points of equal field value • Isotherms- lines of equal temperature • Isobars- lines of equal air pressure • Contour lines- lines of equal elevation Draw the isolines! (connect points of equal values) Isolines Drawn in Red Isotherm Map Isobar Map Topographic Maps • Topographic map (contour map)- shows the elevation field using contour lines • Elevation - the vertical height above & below sea level Why use sea level as a reference point? Topographic Maps Reading Contour lines Contour interval- the difference in elevation between consecutive contour lines Subtract the difference in value of two nearby contour lines and divide by the number of spaces between the contour lines Elevation – Elevation # spaces between 800- 700 =?? 5 Contour Interval = ??? Rules of Contour Lines • Never intersect, branch or cross • Always close on themselves (making circle) or go off the edge of the map • When crossing a stream, form V’s that point uphill (opposite to water flow) • Concentric circles mean the elevation is increasing toward the top of a hill, unless there are hachures showing a depression • Index contour- thicker, bolder contour lines on contour maps, usually every 5 th line • Benchmark - BMX or X shows where a metal marker is in the ground and labeled with an exact elevation ‘Hills’ & ‘Holes’ A depression on a contour map is shown by contour lines with small marks pointing toward the lowest point of the depression. The first contour line with the depression marks (hachures) and the contour line outside it have the same elevation. -

Gradual Generalization of Nautical Chart Contours with a B-Spline Snake Method

GRADUAL GENERALIZATION OF NAUTICAL CHART CONTOURS WITH A B-SPLINE SNAKE METHOD BY DANDAN MIAO BS in Geographic Information Systems, Wuhan University, 2009 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Ocean Engineering September, 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 2014 Dandan Miao This thesis has been examined and approved. Dr. Brian Calder, Associate Research Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Kurt Schwehr Affiliate Associate Professor of Ocean Engineering Dr. Steve Wineberg Lecturer, Mathematics and Statistics Date v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was sponsored by NOAA grant NA10NOS400007, and supported by the Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping. Professor Larry Mayer introduced me to the world of Ocean Mapping, and taught me new information about geological oceanography; Professor Brian Calder initiated this study and has always been able to selflessly help me with any questions; Professor Steven Wineberg gave me many insights of how to transfer math concepts to graphic behavior; Professor Kurt Schwehr helped me with many intelligent thoughts and suggestion about computer programming implementation. I am grateful for all their selfless help and patience, and I would like to thank all of them for their guidance, encouragement and proof-reading of this thesis: without them and CCOM’s support, this work would not have happened. Finally, I would like to thank my parents and friends, for encouragement and trust. Your love and faith gave me the strength to keep holding on and finally make it work! Love you all! With greatest thankfulness, Dandan Miao vi TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................