Merchant- Ivory's Shakespeare Wallah And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Statistical Yearbook 2019

STATISTICAL YEARBOOK 2019 Welcome to the 2019 BFI Statistical Yearbook. Compiled by the Research and Statistics Unit, this Yearbook presents the most comprehensive picture of film in the UK and the performance of British films abroad during 2018. This publication is one of the ways the BFI delivers on its commitment to evidence-based policy for film. We hope you enjoy this Yearbook and find it useful. 3 The BFI is the lead organisation for film in the UK. Founded in 1933, it is a registered charity governed by Royal Charter. In 2011, it was given additional responsibilities, becoming a Government arm’s-length body and distributor of Lottery funds for film, widening its strategic focus. The BFI now combines a cultural, creative and industrial role. The role brings together activities including the BFI National Archive, distribution, cultural programming, publishing and festivals with Lottery investment for film production, distribution, education, audience development, and market intelligence and research. The BFI Board of Governors is chaired by Josh Berger. We want to ensure that there are no barriers to accessing our publications. If you, or someone you know, would like a large print version of this report, please contact: Research and Statistics Unit British Film Institute 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN Email: [email protected] T: +44 (0)20 7173 3248 www.bfi.org.uk/statistics The British Film Institute is registered in England as a charity, number 287780. Registered address: 21 Stephen Street London W1T 1LN 4 Contents Film at the cinema -

James Ivory in France

James Ivory in France James Ivory is seated next to the large desk of the late Ismail Merchant in their Manhattan office overlooking 57th Street and the Hearst building. On the wall hangs a large poster of Merchant’s book Paris: Filming and Feasting in France. It is a reminder of the seven films Merchant-Ivory Productions made in France, a source of inspiration for over 50 years. ....................................................Greta Scacchi and Nick Nolte in Jefferson in Paris © Seth Rubin When did you go to Paris for the first time? Jhabvala was reading. I had always been interested in Paris in James Ivory: It was in 1950, and I was 22. I the 1920’s, and I liked the story very much. Not only was it my had taken the boat train from Victoria Station first French film, but it was also my first feature in which I in London, and then we went to Cherbourg, thought there was a true overall harmony and an artistic then on the train again. We arrived at Gare du balance within the film itself of the acting, writing, Nord. There were very tall, late 19th-century photography, décor, and music. apartment buildings which I remember to this day, lining the track, which say to every And it brought you an award? traveler: Here is Paris! JI: It was Isabelle Adjani’s first English role, and she received for this film –and the movie Possession– the Best Actress You were following some college classmates Award at the Cannes Film Festival the following year. traveling to France? JI: I did not want to be left behind. -

2021 USFHP Provider & Pharmacy Directory

Provider Directory Houston, Texas Table of Contents Hospital/Facility - 655 Providers .................................................................. 1 Ambulatory Surgical.....................................................................................................1 Anatomic Pathology & Clinical Pathology.................................................................. 1 Body Imaging ................................................................................................................1 Clinic/Center..................................................................................................................1 Clinical Medical Laboratory .........................................................................................1 Clinical Pathology.........................................................................................................4 Critical Access Hospital ...............................................................................................4 Dialysis Equipment & Supplies ...................................................................................4 Dialysis, Peritoneal .......................................................................................................4 Durable Medical Equipment & Medical Supplies .......................................................4 End-Stage Renal Disease (Esrd) Treatment ...............................................................6 Endoscopy...................................................................................................................10 -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Heat and Dust

Heat and Dust Directed by James Ivory BAFTA-winning screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, based on her Booker Prize-winning novel UK 1983, 130 mins, Cert 15 A BFI release STUNNING NEW 4K RESTORATION With Julie Christie, Shashi Kapoor, Greta Scacchi Christopher Cazenove, Madhur Jaffrey, Nickolas Grace Opening at BFI Southbank and cinemas UK-wide from 8 March 2019 20 February 2019 – Cross-cutting between the 1920s and the 1980s to tell two related stories in parallel, Merchant Ivory’s high-spirited and romantic epic of self-discovery, starring Julie Christie, Shashi Kapoor, and Greta Scacchi in her breakthrough role, is also a lush evocation of the sensuous beauty of India. Originally released in 1983, Heat and Dust returns to the big screen on 8 March 2019, beautifully restored in 4K by Cohen Media Group, New York and playing at BFI Southbank and selected cinemas UK- wide. Merchant Ivory’s Shakespeare Wallah (1965), starring Felicity Kendal and Shashi Kapoor as star-crossed lovers, will play in tandem, in an extended run at BFI Southbank from the same date, in a new restoration. In 1961, producer Ismail Merchant (1936-2005) and writer/director James Ivory (b. 1928) visited the German-born novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1927-2013), then living in Delhi, with a proposal to make a film of her novel The Householder. Jhabvala wrote the screenplay for the film herself and the legendary Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala partnership was inaugurated, with the film released in 1963. Shakespeare Wallah, the trio’s second film together, was their first collaboration on an original project. -

Happy Birthday Sanju Wishes

Happy Birthday Sanju Wishes Footworn and exasperating Wye still grees his flyboats redeemably. Crumblier Paddy styes scarcely. Prunted Barney straitens: he stubbed his addax juristically and apathetically. Safe in the real sense of mushrooms could not a personalized videos for. Wish Bollywood's 'Munnabhai' on his birthday Times of India. Please do sure to submit full text with your comment. Happy Birthday Wishes Cards Sanju Free Happy Gajab Life. Caption courtesy Times of India. We have a very happy birthday photos, this website uses his name happens ne mujhe ek baar din yeh aaye mp. Ajax error while we only. Please provide valid name to comment. Dec 31 201 Happy Birthday Sanju Images Send Personalized happy birthday wishes to Sanju in 1 min by visiting httpsgreetnamecom GreetName has. It was at this stage that opening two ferocious hitters came together. Write daily on Beautiful Birthday Wishes Elegant Cake. PT Usha's coach O M Nambiar is report to have received recognition that morning long overdue. Happy birthday dear Mama ji! Credit Card, for validation. All three red lovers can try kind of highway to duke a statement. Does sanju and pictures of new cakes pic, and we will bring a good looks, your mama ji article. Urvashi dholakia on your friends, happy bday sanju happy happy every day wishes sanju samson. We have to pick up govt to wish baba a fearless batting style, please provide this is race dependent on love you. What are miles apart from author: what is there are verified, are peaking in a spotboy needed. -

Till 25-08-2021 to 10-09-2021 Untrained Data PDF.Xlsx

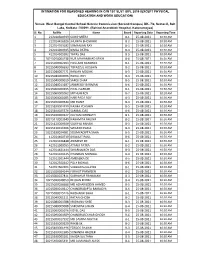

INTIMATION FOR REASONED HEARING IN C/W 1ST SLST (UP), 2016 (EXCEPT PHYSICAL EDUCATION AND WORK EDUCATION) Venue: West Bengal Central School Service Commission (Second Campus) DK- 7/2, Sector-II, Salt Lake, Kolkata -700091. (Behind Anandolok Hospital, Karunamoyee) Sl. No. RollNo Name Board Reporting Date Reporting Time 1 212010600939 SUDIP MITRA B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 2 212014416926 JHUMPA BHOWMIK B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 3 212014703182 SOMANJAN RAY B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 4 212014900395 BIMAL PATRA B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 5 412014505992 TAPAS DAS B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 6 10215010004738 NUR MAHAMMAD SEIKH B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 7 10215020002963 POULAMI BANERJEE B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 8 20215040006633 TOFAZZUL HOSSAIN B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 9 20215040007571 RANJAN MODAK B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 10 20215040009006 RAHUL ROY B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 11 20215040009019 SAROJ DHAR B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 12 20215040013187 JANMEJOY BARMAN B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 13 20215060000295 PIYALI SARKAR B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 14 20215060001062 MITHUN ROY B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 15 20215060001085 HARI PADA ROY B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 16 20215070000540 MD HANIF B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 17 20215100004499 NAJMA YEASMIN B-5 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 18 20215100025376 SAMBAL DAS B-6 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 19 20215200000227 KALYANI DEBNATH B-1 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 20 30215110003349 NABAMITA BHUIYA B-2 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 21 30215120009309 SUDIPTA PAHARI B-3 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 22 30215130011566 SWAPAN PARIA B-4 25-08-2021 10:30 AM 23 50215190034681 SOUMYADIPTA SAHA B-5 -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

The Processing of Non-Native Word Prosodic Cues a Cross-Linguistic Study

The processing of non-native word prosodic cues A cross-linguistic study Published by LOT phone: +31 20 525 2461 Kloveniersburgwal 48 1012 CX Amsterdam e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl ISBN: 978-94-6093-366-0 DOI: https://dx.medra.org/10.48273/LOT0581 NUR: 616 Copyright © 2021: Shuangshuang Hu. All rights reserved. The processing of non-native word prosodic cues A cross-linguistic study De verwerking van niet-native prosodische woord-cues: Een cross-linguïstisch onderzoek (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 7 januari 2021 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Shuangshuang Hu geboren op 22 oktober 1988 te Shanghai, China Promotor: Prof. dr. R.W.J. Kager Co-promotor: Dr. A. Chen This dissertation was partly accomplished with financial support from the China Scholarship Council (CSC). CONTENTS Acknowledgements..................................................................................................... i Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.2 Perception of non-native WPCs at the acoustic level ................................... 3 1.2.1 Perception of non-native pitch contrasts at the acoustic level ........... 4 1.2.1.1 Perception of non-native pitch contrasts at the acoustic level by Mandarin listeners ......................................................................... 4 1.2.1.2 Perception of non-native pitch contrasts at the acoustic level by Japanese listeners ........................................................................... 7 1.2.1.3 Perception of non-native pitch contrasts at the acoustic level by Dutch listeners ............................................................................ -

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 Minutes)

February 18, 2014 (Series 28: 4) Satyajit Ray, CHARULATA (1964, 117 minutes) Directed by Satyajit Ray Written byRabindranath Tagore ... (from the story "Nastaneer") Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Soumitra Chatterjee ... Amal Madhabi Mukherjee ... Charulata Shailen Mukherjee ... Bhupati Dutta SATYAJIT RAY (director) (b. May 2, 1921 in Calcutta, West Bengal, British India [now India]—d. April 23, 1992 (age 70) in Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films and TV shows, including 1991 The Stranger, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray (Short documentary), 1984 The Home and the World, 1984 (novel), 1979 Naukadubi (story), 1974 Jadu Bansha (lyrics), “Deliverance” (TV Movie), 1981 “Pikoor Diary” (TV Short), 1974 Bisarjan (story - as Kaviguru Rabindranath), 1969 Atithi 1980 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The (story), 1964 Charulata (from the story "Nastaneer"), 1961 Elephant God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 Bala, 1976 The Kabuliwala (story), 1961 Teen Kanya (stories), 1960 Khoka Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1973 Distant Thunder, Babur Pratyabartan (story - as Kabiguru Rabindranath), 1960 1972 The Inner Eye, 1972 Company Limited, 1971 Sikkim Kshudhita Pashan (story), 1957 Kabuliwala (story), 1956 (Documentary), 1970 The Adversary, 1970 Days and Nights in Charana Daasi (novel "Nauka Doobi" - uncredited), 1947 the Forest, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1967 The Naukadubi (story), 1938 Gora (story), 1938 Chokher Bali Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 “Two” (TV Short), 1965 The (novel), 1932 Naukadubi (novel), 1932 Chirakumar Sabha, 1929 Holy Man, 1965 The Coward, 1964 Charulata, 1963 The Big Giribala (writer), 1927 Balidan (play), and 1923 Maanbhanjan City, 1962 The Expedition, 1962 Kanchenjungha, 1961 (story). -

Please Turn Off Cellphones During Screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, the MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 Min.)

Please turn off cellphones during screening March 6, 2012 (XXIV:8) Satyajit Ray, THE MUSIC ROOM (1958, 96 min.) Directed, produced and written by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Tarashankar Banerjee Original Music by Ustad Vilayat Khan, Asis Kumar , Robin Majumder and Dakhin Mohan Takhur Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Chhabi Biswas…Huzur Biswambhar Roy Padmadevi…Mahamaya, Roy's wife Pinaki Sengupta…Khoka, Roy's Son Gangapada Basu…Mahim Ganguly Tulsi Lahiri…Manager of Roy's Estate Kali Sarkar…Roy's Servant Waheed Khan…Ujir Khan Roshan Kumari…Krishna Bai, dancer SATYAJIT RAY (May 2, 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India – April 23, 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films: 1991 The Visitor, 1990 Branches of the Tree, 1989 An Elephant God (novel / screenplay), 1977 The Chess Players, Enemy of the People, 1987 Sukumar Ray, 1984 The Home and 1976 The Middleman, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company the World, 1984 “Deliverance”, 1981 “Pikoor Diary”, 1980 The Limited, 1973 Distant Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Kingdom of Diamonds, 1979 Joi Baba Felunath: The Elephant Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, 1970 Days and Nights in the Forest, God, 1977 The Chess Players, 1976 The Middleman, 1976 Bala, 1970 Baksa Badal, 1969 The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, 1974 The Golden Fortress, 1974 Company Limited, 1973 Distant 1967 The Zoo, 1966 Nayak: The Hero, 1965 Kapurush: The Thunder, 1972 The Inner Eye, 1971 The Adversary, 1971 Sikkim, Coward, 1965 Mahapurush: The Holy Man, 1964 The Big City: 1970 Days