Seasonal Migrations of Black Bears (Ursus Americanus): Causes and Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuja Plicata Has Many Traditional Uses, from the Manufacture of Rope to Waterproof Hats, Nappies and Other Kinds of Clothing

photograph © Daniel Mosquin Culturally modified tree. The bark of Thuja plicata has many traditional uses, from the manufacture of rope to waterproof hats, nappies and other kinds of clothing. Careful, modest, bark stripping has little effect on the health or longevity of trees. (see pages 24 to 35) photograph © Douglas Justice 24 Tree of the Year : Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don In this year’s Tree of the Year article DOUGLAS JUSTICE writes an account of the western red-cedar or giant arborvitae (tree of life), a species of conifers that, for centuries has been central to the lives of people of the Northwest Coast of America. “In a small clearing in the forest, a young woman is in labour. Two women companions urge her to pull hard on the cedar bark rope tied to a nearby tree. The baby, born onto a newly made cedar bark mat, cries its arrival into the Northwest Coast world. Its cradle of firmly woven cedar root, with a mattress and covering of soft-shredded cedar bark, is ready. The young woman’s husband and his uncle are on the sea in a canoe carved from a single red-cedar log and are using paddles made from knot-free yellow cedar. When they reach the fishing ground that belongs to their family, the men set out a net of cedar bark twine weighted along one edge by stones lashed to it with strong, flexible cedar withes. Cedar wood floats support the net’s upper edge. Wearing a cedar bark hat, cape and skirt to protect her from the rain and INTERNATIONAL DENDROLOGY SOCIETY TREES Opposite, A grove of 80- to 100-year-old Thuja plicata in Queen Elizabeth Park, Vancouver. -

Caterpillars Moths Butterflies Woodies

NATIVE Caterpillars Moths and utter flies Band host NATIVE Hackberry Emperor oodies PHOTO : Megan McCarty W Double-toothed Prominent Honey locust Moth caterpillar Hackberry Emperor larva PHOTO : Douglas Tallamy Big Poplar Sphinx Number of species of Caterpillars n a study published in 2009, Dr. Oaks (Quercus) 557 Beeches (Fagus) 127 Honey-locusts (Gleditsia) 46 Magnolias (Magnolia) 21 Double-toothed Prominent ( Nerice IDouglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D, chair of the Cherries (Prunus) 456 Serviceberry (Amelanchier) 124 New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus) 45 Buttonbush (Cephalanthus) 19 bidentata ) larvae feed exclusively on elms Department of Entomology and Wildlife Willows (Salix) 455 Larches or Tamaracks (Larix) 121 Sycamores (Platanus) 45 Redbuds (Cercis) 19 (Ulmus), and can be found June through Ecology at the University of Delaware Birches (Betula) 411 Dogwoods (Cornus) 118 Huckleberry (Gaylussacia) 44 Green-briar (Smilax) 19 October. Their body shape mimics the specifically addressed the usefulness of Poplars (Populus) 367 Firs (Abies) 117 Hackberry (Celtis) 43 Wisterias (Wisteria) 19 toothed shape of American elm, making native woodies as host plants for our Crabapples (Malus) 308 Bayberries (Myrica) 108 Junipers (Juniperus) 42 Redbay (native) (Persea) 18 them hard to spot. The adult moth is native caterpillars (and obviously Maples (Acer) 297 Viburnums (Viburnum) 104 Elders (Sambucus) 42 Bearberry (Arctostaphylos) 17 small with a wingspan of 3-4 cm. therefore moths and butterflies). Blueberries (Vaccinium) 294 Currants (Ribes) 99 Ninebark (Physocarpus) 41 Bald cypresses (Taxodium) 16 We present here a partial list, and the Alders (Alnus) 255 Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya) 94 Lilacs (Syringa) 40 Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne) 15 Honey locust caterpillar feeds on honey number of Lepidopteran species that rely Hickories (Carya) 235 Hemlocks (Tsuga) 92 Hollies (Ilex) 39 Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron) 15 locust, and Kentucky coffee trees. -

Dying Cedar Hedges —What Is the Cause?

Points covered in this factsheet Symptoms Planting problems Physiological effects Environmental, Soil and Climate factors Insect, Disease and Vertebrate agents Dying Cedar Hedges —What Is The Cause? Attractive and normally trouble free, cedar trees can be great additions to the landscape. Dieback of cedar hedging in the landscape is a common prob- lem. In most cases, it is not possible to pinpoint one single cause. Death is usually the result of a combination of envi- ronmental stresses, soil factors and problems originating at planting. Disease, insect or animal injury is a less frequent cause. Identifying The Host Certain species of cedar are susceptible to certain problems, so identifying the host plant can help to identify the cause and whether a symptom is an issue of concern or is normal for that plant. The most common columnar hedging cedars are Thuja plicata (Western Red Cedar - native to the West Coast) and Thuja occidentalis (American Arborvitae or Eastern White ICULTURE, PLANT HEALTH UNIT Cedar). Both species are often called arborvitae. Common varieties of Western Red ce- dar are ‘Emerald Giant’, ‘Excelsa’ and Atrovirens’. ‘Smaragd’ and ‘Pyramidalis’ are com- mon varieties of Eastern White cedar hedging. Species of Cupressus (Cypress), Chamaecyparis nootkatensis (Yellow Cedar or False Cypress) and Chamaecyparis law- soniana (Port Orford Cedar or lawsom Cypress) are also used in hedging. Symptoms The pattern of symptom development/distribution can provide a clue to whether the prob- lem is biotic (infectious) or abiotic (non-infectious). Trees often die out in a group, in one section of the hedge, or at random throughout the hedge. -

Thuja Occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Dissertations and Theses Fall 12-16-2017 Plant Species Richness and Diversity of Northern White-Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables Robert Smith SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds Recommended Citation Smith, Robert, "Plant Species Richness and Diversity of Northern White-Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) Swamps in Northern New York: Effects and Interactions of Multiple Variables" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. 7. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/7 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PLANT SPECIES RICHNESS AND DIVERSITY OF NORTHERN WHITE-CEDAR (Thuja occidentalis) SWAMPS IN NORTHERN NEW YORK: EFFECTS AND INTERACTIONS OF MULTIPLE VARIABLES by Robert L. Smith II A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York November 2017 Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Approved by: Donald J. Leopold, Major Professor René H. Germain, Chair, Examining Committee Donald J. Leopold, Department Chair S. Scott Shannon, Dean, The Graduate School ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Donald J. Leopold, for his great advice during our many meetings and email exchanges. In addition, his visit to my study site and recommended improvements to my thesis were very much appreciated. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Behavioral Responses of American Black Bears to Reduced Natural Foods: Home Range Size and Seasonal Migrations

BEHAVIORAL RESPONSES OF AMERICAN BLACK BEARS TO REDUCED NATURAL FOODS: HOME RANGE SIZE AND SEASONAL MIGRATIONS Spencer J. Rettler1, David L. Garshelis, Andrew N. Tri, John Fieberg1, Mark A. Ditmer2 and James Forester1 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS American black bears (Ursus americanus) in the Chippewa National Forest demonstrated appreciable fat reserves and stable reproduction despite a substantial decline in natural food availability over a 30-year period. Here we investigated potential strategies that bears may have employed to adapt to this reduction in food. We hypothesized that bears increased their home range sizes to encompass more food and/or increased the frequency, duration and distance of large seasonal migrations to seek out more abundant food resources. We estimated home range sizes using both Minimum Convex Polygon and Kernel Density Estimate approaches and developed a method to identify seasonal migrations. Male home range sizes in the 2010s were approximately twice the size of those in the 1980s; whereas, female home ranges tripled in size from the 1980s to the 2010s. We found little difference in migration patterns with only slight changes to duration. Our results supported our hypothesis that home range size increased in response to declining foods, which may explain why body condition and reproduction has not changed. However, these increased movements, in conjunction with bears potentially consuming more human-related foods in the fall, may alter harvest vulnerability, and should be considered when managing the bear hunt. INTRODUCTION As a large generalist omnivore, American black bears (Ursus americanus; henceforth black bear or bear) demonstrate exceptional plasticity in response to changes in food availability. -

Cornus Kousa Kousa Dogwood1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-191 November 1993 Cornus kousa Kousa Dogwood1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Kousa Dogwood grows 15 to 20 feet tall and has beautiful exfoliating bark, long lasting flowers, good fall color, and attractive fruit (Fig. 1). Branches grow upright when the tree is young, but appear in horizontal layers on mature trees. The crown eventually grows wider than it is tall on many specimens. It would be difficult to use too many Kousa Dogwoods. The white, pointed bracts are produced a month later than Flowering Dogwood and are effective for about a month, sometimes longer. The red fruits are edible and they look like a big round raspberry. Birds devour the fruit quickly. Fall color varies from dull red to maroon. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Cornus kousa Pronunciation: KOR-nus KOO-suh Common name(s): Kousa Dogwood, Chinese Dogwood, Japanese Dogwood Family: Cornaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 8 (Fig. 2) Figure 1. Young Kousa Dogwood. Origin: not native to North America Uses: container or above-ground planter; near a deck DESCRIPTION or patio; screen; specimen Availability: generally available in many areas within Height: 15 to 20 feet its hardiness range Spread: 15 to 20 feet Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more or less identical crown forms Crown shape: round Crown density: dense Growth rate: slow 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-191, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. -

![Alangium-Presentation [Lecture Seule]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3512/alangium-presentation-lecture-seule-243512.webp)

Alangium-Presentation [Lecture Seule]

A Targeted Enrichment Strategy for Sequencing of Medicinal Species in the Indonesian Flora Berenice Villegas-Ramirez, Erasmus Mundus Master Programme in Evolutionary Biology (MEME) Supervisors: Dr. Sarah Mathews, Harvard University Dr. Hugo de Boer, Uppsala University Introduction • Up to 70,000 plant species are used worldwide in traditional medicine. • At least 20,000 plant taxa have recorded medicinal uses. • Main commercial producers are in Asia: China, India, Indonesia, and Nepal. • Indonesia has c. 7000 plant species of documented medicinal use. • But…… Transmigration and Farming Herbarium Specimens • Plastid genes rbcL and matK have been be adopted as the official DNA barcodes for all land plants. • rbcl ~ 1428 bp • matK ~ 1500 bp • Herbarium specimens often require more attempts at amplification with more primer combinations. • Higher possibility of obtaining incorrect sequences through increased chances of samples becoming mixed up or contaminated. • Lower performance using herbarium material due to lower amplification success. • Caused by severe degradation of DNA into low molecular weight fragments. • But fragmented DNA is not a curse! Next-Generation Sequencing • Fragmented DNA is less of a problem • Only a few milligrams of material are necessary Targeted Enrichment • Defined regions in a genome are selectively captured from a DNA sample prior to sequencing. • The genomic complexity in a sample is reduced. • More time- and cost-effective. Hybrid Capture Targeted Enrichment • Library DNA is hybridized to a probe. • Pre-prepared DNA or RNA fragments complementary to the targeted regions of interest. • Non-specific hybrids are removed by washing. • Targeted DNA is eluted. Easy to use, utilizes a small amount of input DNA (<1-3 ug), and number of loci (target size) is large (1-50 Mb). -

The Role of Forage Availability on Diet Choice and Body Condition in American Beavers (Castor Canadensis)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers National Park Service 2013 The oler of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud Northern Michigan University Steve K. Windels National Park Service Jerrold L. Belant Mississippi State University John G. Bruggink Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark Severud, William J.; Windels, Steve K.; Belant, Jerrold L.; and Bruggink, John G., "The or le of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis)" (2013). U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers. 124. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the National Park Service at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. National Park Service Publications and Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Mammalian Biology 78 (2013) 87–93 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Mammalian Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mambio Original Investigation The role of forage availability on diet choice and body condition in American beavers (Castor canadensis) William J. Severud a,∗, Steve K. Windels b, Jerrold L. Belant c, John G. Bruggink a a Northern Michigan University, Department of Biology, 1401 Presque Isle Avenue, Marquette, MI 49855, USA b National Park Service, Voyageurs National Park, 360 Highway 11 East, International Falls, MN 56649, USA c Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS 39762, USA article info abstract Article history: Forage availability can affect body condition and reproduction in wildlife. -

Oaks for Nebraska Justin R

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications Nebraska Statewide Arboretum 2013 Oaks for Nebraska Justin R. Evertson University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs Part of the Botany Commons, and the Forest Biology Commons Evertson, Justin R., "Oaks for Nebraska" (2013). Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications. 1. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/arboretumpubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Statewide Arboretum at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Statewide Arboretum Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Oaks for Nebraska Justin Evertson, Nebraska Statewide Arboretum arboretum.unl.edu or retreenebraska.unl.edu R = belongs to red oak group—acorns mature over two seasons & leaves typically have pointed lobes. W = belongs to white oak group— acorns mature in one season & leaves typically have rounded lobes. Estimated size range is height x spread for trees growing in eastern Nebraska. A few places to see oaks: Indian Dwarf chinkapin oak, Quercus Cave State Park; Krumme Arboretum Blackjack oak, Quercus prinoides (W) in Falls City; Peru State College; marilandica (R) Variable habit from shrubby to Fontenelle Nature Center in Bellevue; Shorter and slower growing than tree form; prolific acorn producer; Elmwood Park in Omaha; Wayne most oaks with distinctive tri- can have nice yellow fall color; Park in Waverly; University of lobed leaves; can take on a very national champion grows near Nebraska Lincoln; Lincoln Regional natural look with age; tough and Salem Nebraska; 10-25’x 10-20’. -

Bur Oak Quercus Macrocarpa Tree Bark ILLINOIS RANGE

bur oak Quercus macrocarpa Kingdom: Plantae FEATURES Division: Magnoliophyta The deciduous bur oak tree may grow to 120 feet Class: Magnolioposida tall with a trunk diameter of five feet. Its bark is dark Order: Fagales brown or yellow-brown with deep furrows. The bud is rounded or slightly pointed at the tip, yellow- Family: Fagaceae brown to red-brown and hairy. The simple leaves are ILLINOIS STATUS arranged alternately along the stem. The leaf blade is broad at the upper end and coarsely round- common, native toothed. The leaf has five to seven lobes. Each leaf is © Guy Sternberg dark green and smooth or slightly hairy on the upper surface and pale and hairy on the lower surface. The leaf may be 14 inches long and seven inches wide with a one inch leaf stalk. Male and female flowers are separate but located on the same tree. Neither type of flower has petals. Male (staminate) flowers are arranged in drooping catkins, while the female (pistillate) flowers are clustered in a small group. The fruit is a solitary acorn. The dark brown acorn may be ovoid to ellipsoid and up to one and three- quarter inches long. The hairy cup covers half to nearly all of the nut and has a fringe of long scales. BEHAVIORS The bur oak may be found statewide in Illinois. This tree tree grows almost anywhere, from dry ridges to bottomland woods. The bur oak flowers in April and May, about the time that its leaves begin to unfold. ILLINOIS RANGE Its heavy, hard wood is used in making cabinets, for ship building, for fence posts and for fuel. -

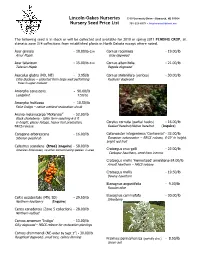

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata