A Farm Level Analysis of Wheat Growers in Irrigated Punjab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Map (PDF | 4.45

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - PUNJAB ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K.P. ! ! ! ! ! ! Murree ! Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Hasan Abdal Tehsil ! Attock Tehsil ! Kotli Sattian Tehsil ! Taxila Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Attock ! ! ! ! Jand Tehsil ! Kahuta ! Fateh Jang Tehsil Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi ! ! Pindi Gheb Tehsil ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R ! ! ! ! Gujar Khan Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohawa ! Tehsil ! ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N Chakwal Chakwal ! ! ! Tehsil Sarai Alamgir Tehsil ! ! Tala Gang Tehsil Jhelum Tehsil ! Isakhel Tehsil ! Jhelum ! ! ! Choa Saidan Shah Tehsil Kharian Tehsil Gujrat Mianwali Tehsil Mianwali Gujrat Tehsil Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil Sialkot Tehsil Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Malakwal Tehsil Phalia Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Sialkot Daska Tehsil Khushab Piplan Tehsil Tehsil Wazirabad Tehsil Pasrur Tehsil Narowal Shakargarh Tehsil Shahpur Tehsil Khushab Gujranwala Bhalwal Hafizabad Tehsil Gujranwala Tehsil Tehsil Narowal Tehsil Sargodha Kamoke Tehsil Kalur Kot Tehsil Sargodha Tehsil Hafizabad Nowshera Virkan Tehsil Pindi Bhattian Tehsil Noorpur Sahiwal Tehsil Tehsil Darya Khan Tehsil Sillanwali Tehsil Ferozewala Tehsil Safdarabad Tehsil Sheikhupura Tehsil Chiniot -

Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan

RESEARCH TO FILL CRITICAL EVIDENCE GAPS CLIMATE CHANGE, RESILIENCE, AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN PAKISTAN A CASE STUDY OF THE 2010 FLOODS IN MIANWALI DISTRICT The Population Council is prioritizing research to strengthen the evidence on resilience among those who are vulnerable to environmental stressors. This research is designed to fill evidence gaps and generate the evidence decision-makers need to develop and implement effective programs and policies. popcouncil.org/research/climate-change-vulnerability- and-resilience For information on partnership and funding opportunities, contact: Jessie Pinchoff, [email protected] Suggested citation: Sathar, Zeba, A., Muhammad Khalil, Sabahat Hussain, Maqsood Sadiq, and Kiren Khan. 2018. “Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan: A Case Study of the 2010 Floods in Mianwali District.” Pakistan: Population Council. Photos: Population Council Staff Islamabad © 2018 The Population Council, Inc ii In 2010, Pakistan experienced massive flooding that went on uninterrupted for more than eight weeks, and seriously affected more than 20 million people. This study explores the effects of the floods on one of the most adversely affected districts, Mianwali, in Punjab province. A multidisciplinary approach is taken to analyze available demographic and geospatial data for a deeper understanding of the community- level vulnerability to the 2010 floods, to identify demographic changes potentially associated with the floods, and to describe the implications for building resilience in regions at high risk of large-scale flood events. We focus on four areas pertaining to resilience: 1. Movements and migration processes 2. Shifts in poverty levels and living conditions 3. Changes in livelihood activities 4. Health-seeking behavior, particularly fertility-related processes This study highlights the need to include demographic and health information in the analysis of natural disasters. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

List of Canidates for Recuritment of Mali at Police College Sihala

LIST OF CANIDATES FOR RECURITMENT OF MALI AT POLICE COLLEGE SIHALA not Sr. No Sr. Name Address CNIC No CNIC age on07-04-21age Remarks Attached Qulification Date ofBirth Date Father Name Father Appliedin Quota AppliedPost forthe Date ofTestPractical Date Home District-DomicileHome Affidavit attached / Not Not Affidavit/ attached Day Month Year Experienceor Certificate attached 1 Ghanzafar Abbas Khadim Hussain Chak Rohacre Teshil & Dist. Muzaffargarh Mali Open M. 32304-7071542-9 Middle 01-01-86 7 4 35 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 W. No. 2 Mohallah Churakil Wala Mouza 2 Mohroz Khan Javaid iqbal Pirhar Sharqi Tehsil Kot Abddu Dist. Mali Open M. 32303-8012130-5 Middle 12-09-92 26 7 28 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Muzaffargarh Ghulam Rasool Ward No. 14 F Mohallah Canal Colony 3 Muhammad Waseem Mali Open M. 32303-6730051-9 Matric 01-12-96 7 5 24 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Khan Tehsil Kot Addu Dist. Muzaffargrah Muhammad Kamran Usman Koryia P-O Khas Tehsil & Dist. 4 Rasheed Ahmad Mali Open M. 32304-0582657-7 F.A 01-08-95 7 9 25 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Rasheed Muzaffargrah Muhammad Imran Mouza Gul Qam Nashtoi Tehsil &Dist. 5 Ghulam Sarwar Mali Open M. 32304-1221941-3 Middle 12-04-88 26 0 33 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Sarwar Muzaffargrah Nohinwali, PO Sharif Chajra, Tehsil 7 6 Mujahid Abbas Abid Hussain Mali Open M. 32304-8508933-9 Matric 02-03-91 6 2 30 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 District Muzaffargarh. Hafiz Ali Chah Suerywala Pittal kot adu, Tehsil & 7 Muhammad Akram Mali Disable 32303-2255820-5 Middle 01-01-82 7 4 39 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Mumammad District Muzaffargarh. -

Crop Damage Assessment Along the Indus River

0 1 0 2 K t A 0 s -P . u 1 2 g 4 n 1 u 0 io A 0 rs 0 -0 e 2 0 V 1 0 -2 L F " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !(" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " : " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " y " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " b " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " d " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " e " " " " " " " " " " t " "" " "p " " " " " " " " " " r " !( " " " " !( " " " " !( " " " p " " " " " " " o " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " u " " " " " " " " " " t " " " !( " " " S " " " . " " " " " " " " " " o " " " " " " n " " " " " " " " " " " " " " D" " p " " " nn " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " e " " " " " " " " " " " " r O " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " a M " " " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " aa " " " !( !(r C " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " e L " " " p" " " " " " " " h I " " " " " " " " " tt "" -

Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan: a Case Study of the 2010 Floods in Mianwali District

Population Council Knowledge Commons Poverty, Gender, and Youth Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2018 Climate change, resilience, and population dynamics in Pakistan: A case study of the 2010 floods in Mianwali District Zeba Sathar Population Council Muhammad Khalil Population Council Sabahat Hussain Population Council Maqsood Sadiq Population Council Kiren Khan Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Sathar, Zeba, Muhammad Khalil, Sabahat Hussain, Maqsood Sadiq, and Kiren Khan. 2018. "Climate change, resilience, and population dynamics in Pakistan: A case study of the 2010 floods in Mianwali District." Islamabad: Population Council. This Brief is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. RESEARCH TO FILL CRITICAL EVIDENCE GAPS CLIMATE CHANGE, RESILIENCE, AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN PAKISTAN A CASE STUDY OF THE 2010 FLOODS IN MIANWALI DISTRICT The Population Council is prioritizing research to strengthen the evidence on resilience among those who are vulnerable to environmental stressors. This research is designed to fill evidence gaps and generate the evidence decision-makers need to develop and implement effective programs and policies. popcouncil.org/research/climate-change-vulnerability- and-resilience For information on partnership and funding opportunities, contact: Jessie Pinchoff, [email protected] Suggested citation: Sathar, Zeba, A., Muhammad Khalil, Sabahat Hussain, Maqsood Sadiq, and Kiren Khan. 2018. “Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan: A Case Study of the 2010 Floods in Mianwali District.” Pakistan: Population Council. -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab

p !( !( 23 August 2010 !( FL-2010-000141-PAK S p a t i o - Te m p o r a l F!( lo o d A n a l y s i s a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b , K P K a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n p Version 1.0 !( This map shows daily variation in flo!(od water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindph, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA p Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend 0 25 50 100 AFGHANISTAN !( Image date : August 18-22, 2010 Result show that the flood extent isq® continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil p Source : NASA Pre-Flood River Line (2009) Kilometres of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has q® Airport p Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) !( partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Ti!(bba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages !( ® Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 18) p and 100 towns were identified as severly affepcted by flood waters and vanalysis was performed using geospatial database ® Heliport !( Image date : September 19, 2009 !( v !( Flood Water extent (Aug 19) ! received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS). -

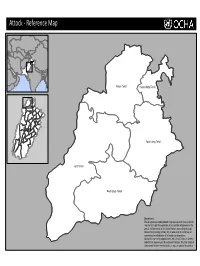

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

1 0012 Aisha 0023

Sr.No. Name of Applicant Address Discipline P-3106 St# 4 Mohallah khalid bin waleed colony Malikpur 203 r.b near Aamir Iqbal B.Sc. (Hons.) Agri. Enng. 0001 nishatabad post 0002 Abdal Inam ul Haq Kotla kahlwan Tehsile Shahkot, District Nankana B.Sc. (Hons.) Microbiology 0003 Abdul Samee Ward No. 3 near Makki Masjid Shaher Sultan Muzaffar Grah Horticulture 0004 Abid Sarwar Department of Irrigation and Drainage UAF M.Sc. (Hons.) Agri. Engg. 0005 Adeel Ahmad Garawala Tehsile Chunnia Distt. Kasur M.Sc. (Hons.) Agri. Extension 0006 Adeela Munawar House No. 176, St # 9, B, nazimabad Faisalabad M.Sc Statistics 0007 Adnan Mehmood House # 672/B-1, Street no.3, Mohallah Inam Abad Pakpattan B.Sc. (Hons.) Microbiology 0008 Adnan Munawar 14-D Ayub Hall UAF/ Chak No. 293/TDA, Tehsil Karor, Distt. Layyah Horticulture 0009 Afaq Mahmood House no.2 Street no. 2, Madina Town block X, FSD DVM Ghali Narang Wali, Mohallah Usman-e-Ghani P/O Rasul Nagar, District Aftab Shoukat M.Phil (Clinical Medicine and Surgery) 0010 Gujranwala, Pakistan 0011 Ahsan Naveed House No. 147 Street No. 2 Faisal Town Arifwala District Pakpattan DVM 0012 Aisha House # 342, Street # 11, Masoodabad, Faisalabad M.Phil in Bioinformatics 0013 Aisha khalid Naeem House No. P-234, Faisal Town, Faisalabad M.Sc. (Hons.) Plant Pathology 0014 Aisha Khalid Naeem House No. P-324, Sector C, Lan 6, Faisal Town District Rajan Pur Punjab M.Sc.(Hons.) PP 0015 Aisha Mahmood 17 Lalazar Colony, University of Agriculture,Faisalabad M.Phil (Physiology) 0016 Aisha Nazir P-500, st-9, Gurunankpura FSD (38000) M.Sc (Hons.) Development Economics 0017 Aisha shehzad House no. -

PUBLIC BUILDINGS: SUMMARY (PKR Million) Provision for 2021-22 No

PUBLIC BUILDINGS: SUMMARY (PKR Million) Provision for 2021-22 No. of Projection for Projection for Type / Sub Sector G. Total Schemes Capital Revenue Foreign Aid 2022-23 2023-24 (Cap + Rev) Archives & Libraries Offices On-going Schemes 7 118.946 20.456 0.000 139.402 89.091 19.080 New Schemes 2 21.765 29.091 0.000 50.856 50.000 40.881 Total:Offices 9 140.711 49.547 0.000 190.258 139.091 59.961 Total: Archives & Libraries 9 140.711 49.547 0.000 190.258 139.091 59.961 Board of Revenue Housing On-going Schemes 1 34.022 0.000 0.000 34.022 0.000 0.000 New Schemes 4 90.421 0.000 0.000 90.421 60.000 60.000 Total:Housing 5 124.443 0.000 0.000 124.443 60.000 60.000 Offices On-going Schemes 20 432.060 7.000 828.000 1,267.060 336.970 350.500 New Schemes 31 1,262.500 430.000 0.000 1,692.500 2,647.210 1,810.000 Total:Offices 51 1,694.560 437.000 828.000 2,959.560 2,984.180 2,160.500 Total: Board of Revenue 56 1,819.003 437.000 828.000 3,084.003 3,044.180 2,220.500 BOR Offices New Schemes 1 5.000 0.000 0.000 5.000 0.000 0.000 Total:Offices 1 5.000 0.000 0.000 5.000 0.000 0.000 Total: BOR 1 5.000 0.000 0.000 5.000 0.000 0.000 C&W Housing On-going Schemes 1 30.000 0.000 0.000 30.000 21.504 20.000 Total:Housing 1 30.000 0.000 0.000 30.000 21.504 20.000 Offices On-going Schemes 2 50.000 0.000 0.000 50.000 237.893 144.475 New Schemes 3 55.497 12.530 0.000 68.027 260.000 255.057 Total:Offices 5 105.497 12.530 0.000 118.027 497.893 399.532 Total: C&W 6 135.497 12.530 0.000 148.027 519.397 419.532 District Development Package Housing New Schemes 4 130.000 0.000 -

33422717.Pdf

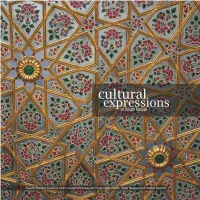

1 Contents 1. PREFACE ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERVIEW OF THE CULTURAL ASSETS OF THE COMMUNITIES OF DISTRICTS MULTAN AND BAHAWALPUR ................................................................... 9 3. THE CAPITAL CITY OF BAHAWALPUR AND ITS ARCHITECTURE ............................ 45 4. THE DECORATIVE BUILDING ARTS ....................................................................................... 95 5. THE ODES OF CHOLISTAN DESERT ....................................................................................... 145 6. THE VIBRANT HERITAGE OF THE TRADITIONAL TEXTILE CRAFTS ..................... 165 7. NARRATIVES ................................................................................................................................... 193 8. AnnEX .............................................................................................................................................. 206 9. GlossARY OF TERMS ................................................................................................................ 226 10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................................. 234 11. REPORTS .......................................................................................................................................... 237 12 CONTRibutoRS ............................................................................................................................ -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A.