Suburban Realities: the Israeli Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISRAEL DISCOUNT BANK LTD. Registration No

T087 Public ISRAEL DISCOUNT BANK LTD. Registration no. 520007030 The securities of the corporation are listed for trading on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange Abbreviated name: Discount Address: 23 Yehuda Halevi St., Tel Aviv 65136, Israel Tel: 972-3-5145582; 972-3-5145544; Fax: 972-3-5171674 e-mail: [email protected] Transmission date: January 2, 2011 Reference: 2011-01-000504 Israel Securities Authority Tel Aviv Stock Exchange Ltd. www.isa.gov.il www.tase.co.il Status of Capital and Registers of Securities of the Corporation and Changes Therein Regulation 31E of the Securities Regulations (Periodic and Immediate Reports), 5730-1970 Regulation 31 (a) of the Securities Regulations (Periodic and Immediate Reports), 5730-1970 1. Status of the securities of the corporation following the change: Stock Issued and Paid-up Capital Number Number of Exchange Registered in Name and Class Securities in Number in Security Current Name of of Security Authorized Previous Registration Number Nominee Capital Report Number Company Ordinary A shares of NIS 0.1 par 691212 1,961,000,000 1,053,794,600 1,053,869,295 788,657,560 value each – Discount A 6% cumulative preferred shares of 6910012 40,000 40,000 40,000 0 NIS 0.00504 par value each – Discount Cumulative Preferred Subordinated debentures – Disc A 6910079 30,000,000 30,000,000 30,000,000 30,000,000 Debentures Unlisted option warrants 6910087 4,053,309 4,053,309 3,399,550 0 convertible into shares – Discount Op 2006 Hybrid capital notes (Series A) – 6910095 1,147,242,389 1,147,242,389 1,147,242,389 -

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL 2013 REPORT BATSHEVA DANCE COMPANY 1 PAGE 0 PAGE Dear friends, Dear friends, In 2013, Batsheva continued its creative momentum. The pinnacle was Ohad Naharin's In the continuous flow of processes and progress, the call to summarize the year new creation, The Hole, in which he proved once again his innovative choreographic offers an opportunity to pause and look back. voice. This fascinating, unique creation won the audience’s heart and also received warm critical praise. In addition, within Batsheva's commitment to encourage and 2013 was full of significant creative processes in the studio and warm dialogue with nurture emerging talent, the Ensemble presented Shula by young choreographer the audience both in Israel and abroad. It was a year of evolution and profundity, Danielle Agami, and this piece, too, won great success. with many moments of beauty and quality. Approximately 94,000 people attended the Company's performances during 2013. The Company toured extensively around the world and held 51 performances for The year's accomplishments belong to everyone – the dancers who shone in their 36,000 spectators abroad, strengthening the Company's international reputation. work; the artistic team, the administration, and the technical crew who devoted Once again the Company was an excellent ambassador for Israel. themselves to creation with passion and inspired joy; the public council members The Company pursued its social and educational activity in Israel. In its series of and the board of directors who accompany us with involvement and love; the morning school shows, a tradition Batsheva has maintained for over a decade, the benefactors who believe in us and who enable us to excel; and the wide audience Ensemble performed for 10,000 students in cities across Israel. -

QUELQUE PART DANS LE DÉSERT 14 Septembre – 2 Décembre 2018 , 2015 (Détail)

QUELQUE PART DANS LE DÉSERT 14 septembre – 2 décembre 2018 , 2015 (détail). Bisharah and Anwar’s Tree Bisharah and Anwar’s Ron Amir, Amir, Ron #expoRonAmir | www.mam.paris.fr CONTENTS OF THE PRESS KIT Press release p.2 p.3 Biography p.5 Exhibition layout p.6 Contents of the catalogue p.7 Catalogue extracts p.10 Practical informations Ron Amir Somewhere in the Desert 14 September 2 December 2018 Ron Amir – Bisharaah nd Anwar’s Tree, 2015 Press preview: Thursday 13 September 11am–2pm Museum director Fabrice Hergott Official opening: Thursday 13 September 6–10pm Exhibition curator Noam Gal The Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris is delighted to be presenting the exhibition Quelque part dans le désert/ Somewhere in the Desert by Israeli Curator at the Musée d’Art photographer Ron Amir. Already shown at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem in 2016, Moderne de la Ville de Paris : the exhibition – 30 large-format colour photographs and 6 videos – looks at the living Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais conditions of Sudanese and Eritrean refugees in the Holot detention centre in the Exhibition - Scenic designer Negev Desert, which has since been shut down. In flight from terrorism and Cécile Degos oppression in their home countries, these migrants were not able to live or work legally in Israel. While allowed to come and go freely during the day, they had to Press officer check in and out each morning and evening. Maud Ohana [email protected] Dating from 2014–2016, Ron Amir's photographs document the refugees' daytime Tel. -

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence

From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Michal Belikoff and Safa Agbaria Edited by Shirley Racah Jerusalem – Haifa – Nazareth April 2014 From Deficits and Dependence to Balanced Budgets and Independence The Arab Local Authorities’ Revenue Sources Research and writing: Michal Belikoff and Safa Ali Agbaria Editing: Shirley Racah Steering committee: Samah Elkhatib-Ayoub, Ron Gerlitz, Azar Dakwar, Mohammed Khaliliye, Abed Kanaaneh, Jabir Asaqla, Ghaida Rinawie Zoabi, and Shirley Racah Critical review and assistance with research and writing: Ron Gerlitz and Shirley Racah Academic advisor: Dr. Nahum Ben-Elia Co-directors of Sikkuy’s Equality Policy Department: Abed Kanaaneh and Shirley Racah Project director for Injaz: Mohammed Khaliliye Hebrew language editing: Naomi Glick-Ozrad Production: Michal Belikoff English: IBRT Jerusalem Graphic design: Michal Schreiber Printed by: Defus Tira This pamphlet has also been published in Arabic and Hebrew and is available online at www.sikkuy.org.il and http://injaz.org.il Published with the generous assistance of: The European Union This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Sikkuy and Injaz and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. The Moriah Fund UJA-Federation of New York The Jewish Federations of North America Social Venture Fund for Jewish-Arab Equality and Shared Society The Alan B. -

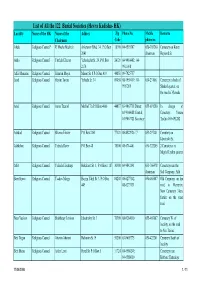

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Made in Israel: Agricultural Exports from Occupied Territories

Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 The Coalition of Women for Peace was established by bringing together ten feminist peace organizations and non-affiliated activist women in Israel. Founded soon after the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, CWP today is a leading voice against the occupation, committed to feminist principles of organization and Jewish-Palestinian partnership, in a relentless struggle for a just society. CWP continuously voices a critical position against militarism and advocates for radical social and political change. Its work includes direct action and public campaigning in Israel and internationally, a pioneering investigative project exposing the occupation industry, outreach to Israeli audiences and political empowerment of women across communities and capacity-building and support for grassroots activists and initiatives for peace and justice. www.coalitionofwomen.org | [email protected] Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Currently, we focus on three main areas of corporate involvement in the occupation: the settlement industry, economic exploitation and control over population. Who Profits operates an online database which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. Moreover, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation – from individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights. -

Israel a History

Index Compiled by the author Aaron: objects, 294 near, 45; an accidental death near, Aaronsohn family: spies, 33 209; a villager from, killed by a suicide Aaronsohn, Aaron: 33-4, 37 bomb, 614 Aaronsohn, Sarah: 33 Abu Jihad: assassinated, 528 Abadiah (Gulf of Suez): and the Abu Nidal: heads a 'Liberation October War, 458 Movement', 503 Abandoned Areas Ordinance (948): Abu Rudeis (Sinai): bombed, 441; 256 evacuated by Israel, 468 Abasan (Arab village): attacked, 244 Abu Zaid, Raid: killed, 632 Abbas, Doa: killed by a Hizballah Academy of the Hebrew Language: rocket, 641 established, 299-300 Abbas Mahmoud: becomes Palestinian Accra (Ghana): 332 Prime Minister (2003), 627; launches Acre: 3,80, 126, 172, 199, 205, 266, 344, Road Map, 628; succeeds Arafat 345; rocket deaths in (2006), 641 (2004), 630; meets Sharon, 632; Acre Prison: executions in, 143, 148 challenges Hamas, 638, 639; outlaws Adam Institute: 604 Hamas armed Executive Force, 644; Adamit: founded, 331-2 dissolves Hamas-led government, 647; Adan, Major-General Avraham: and the meets repeatedly with Olmert, 647, October War, 437 648,649,653; at Annapolis, 654; to Adar, Zvi: teaches, 91 continue to meet Olmert, 655 Adas, Shafiq: hanged, 225 Abdul Hamid, Sultan (of Turkey): Herzl Addis Ababa (Ethiopia): Jewish contacts, 10; his sovereignty to receive emigrants gather in, 537 'absolute respect', 17; Herzl appeals Aden: 154, 260 to, 20 Adenauer, Konrad: and reparations from Abdul Huda, Tawfiq: negotiates, 253 Abdullah, Emir: 52,87, 149-50, 172, Germany, 279-80, 283-4; and German 178-80,230, -

Municipal Amalgamation in Israel

TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Policy Paper No. 2013.02 Jerusalem, July 2013 TAUB CENTER for Social Policy Studies in Israel The Taub Center was established in 1982 under the leadership and vision of Herbert M. Singer, Henry Taub, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. The Center is funded by a permanent endowment created by the Henry and Marilyn Taub Foundation, the Herbert M. and Nell Singer Foundation, Jane and John Colman, the Kolker-Saxon-Hallock Family Foundation, the Milton A. and Roslyn Z. Wolf Family Foundation, and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. This volume, like all Center publications, represents the views of its authors only, and they alone are responsible for its contents. Nothing stated in this book creates an obligation on the part of the Center, its Board of Directors, its employees, other affiliated persons, or those who support its activities. Translation: Ruvik Danieli Editing and layout: Laura Brass Center address: 15 Ha’ari Street, Jerusalem Telephone: 02 5671818 Fax: 02 5671919 Email: [email protected] Website: www.taubcenter.org.il ◘ Internet edition Municipal Amalgamation in Israel Lessons and Proposals for the Future Yaniv Reingewertz Abstract This policy paper deals with municipal amalgamations in Israel, and puts forward a concrete proposal for merging 25 small municipalities with adjacent ones. According to an estimate based on the results of the municipal amalgamations reform carried out in Israel in 2003 (Reingewertz, 2012), thanks to the economies of scale in providing public services, these unifications are expected to generate savings of approximately NIS 131 million per annum. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,412,903 Zemach Et Al

O US005412903A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,412,903 Zemach et al. (45) Date of Patent: May 9, 1995 54). SEA CAGE FISH FARMING SYSTEM 4,244,323 1/1981 Morimura ............................. 43/102 75) Inventors: Shalom Zemach, Kfar Yona; Yitzhak Primary Examiner-Kurt Rowan Farin, Ganei Tikva, both of Israel Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Mark M. Friedman 73) Assignee: Metal Yglem Vashkoht Ltd., Tel 57 ABSTRACT V1V, Israe A fish cage system, which includes a fish cage having (21) Appl. No.: 197993 one or more cables connected to it. The fish cage and 22 Filed: Feb. 17, 1994 cable(s) have a combined buoyancy which is such that 6 at least a portion of the fish cage is normally located at s 8 o was a a a - - - - - - - as a a a AOK34: or above the water surface. The cable(s) are connected 58) FiField fa off Searchsearch ......................- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 43/103,103s s 43. 76 4 s combinedto a sinker buoyancy whose weight of the isfish sufficient cage cable(s). to overcome The sinker the is also connected to a second cable which is connected (56) References Cited to a buoy. The buoy contains a winch for alternately U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS shortening8 and lengtheningg g the effective length of the 1903,276 3/1933 Y 43/102 second cable so as to alternately allow said fish cage to 3,494,064s1 W/ 2/1970 Steina3a ....... ................................... ... float or to submerge. 4,092,797 6/1978 Azurin .................................. 43/102 4,147,130 4/1979 Goguel .................................. 43/102 11 Claims, 4 Drawing Sheets 4477 aaZZZZZZ U.S. -

Modeling Nitrate from Land-Surface to Wells' Perforations Under

Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., doi:10.5194/hess-2017-55, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 20 February 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. Modeling nitrate from land-surface to wells’ perforations under agricultural land: success, failure, and future scenarios in a Mediterranean case study. Yehuda Levy1, Roi H. Shapira2, Benny Chefetz3 and Daniel Kurtzman4 5 1Hydrology and Water Resources Program, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Edmond J. Safra Campus - Givat Ram, 9190401 Jerusalem, Israel 2Mekorot, Israel National Water Company, Lincoln 9, 6713402 Tel-Aviv, Israel 3Department of Soil and Water Sciences, Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 7610001 Rehovot, Israel. 10 4Institute of Soil, Water and Environmental Sciences, Volcani Center, Agricultural Research Organization, HaMaccabim Road 68, 7505101 Rishon LeZion, Israel Correspondence to: Yehuda Levy ([email protected]) Abstract. Contamination of groundwater resources by nitrate leaching under agricultural land is probably the most troublesome agriculture-related water contamination worldwide. Deep soil sampling (10 m) was used to calibrate vertical 15 flow and nitrogen-transport numerical models of the unsaturated zone under different agricultural land uses. Vegetable fields (potato and strawberry) and deciduous orchards (persimmon) in the Sharon area overlying the coastal aquifer of Israel were examined. Average nitrate-nitrogen fluxes below vegetable fields were 210–290 kg ha-1 yr-1, and under deciduous orchards, 110–140 kg ha-1 yr-1. The output water and nitrate-nitrogen fluxes of the unsaturated zone models were used as input data for a three-dimensional flow and nitrate-transport model in the aquifer under an area of 13.3 km2 of agricultural land. -

Clalit Platinum Flyer and Teeth Clinic Listing (2011)

Clalit Mushlam Members Join the Family Health Revolution! * Join Clalit Mushlam Platinum at affordable prices, with no age limit or need for health declaration! New – Optical Treatment for Children Platinum members up to the age of 18 are entitled to free optical glasses each year. The service includes optical glasses or contact lenses (not cosmetic) of up to NIS 600. If the price exceeds NIS 600, members add the difference only. This offer is valid only at Clalit Optic stores across the country. Dental Treatments Platinum members receive FREE preventive dental treatments from age 10 to 18, and over 18 at 70% reduction * Teeth straightening - Orthodontic until 18 at 60% off, and over 18 at 50% reduction * Prosthetic dental treatments, including implants, bridges, false teeth and more at 50% off * All dental treatments are performed at the Clalit Smile chain, which includes 85 clinics around the country. Private Surgery Abroad Platinum members wishing to undergo private surgery abroad will receive participation of expenses of up to 200%, based on the Health Ministry’s price list. For example: a member undergoing bypass surgery abroad, which according to the Health Ministry’s price list costs NIS 57,500, will receive double reimbursement of NIS 115,000. If the surgery includes medical air transport, these expenses will be reimbursed too, up to $10,000. Other expenses such as accommodation for an escort, implants, etc. will also be reimbursed. Private Surgery in Israel Clalit Platinum members are eligible to undergo surgery at any private hospital and choose the surgeon from a list, at extremely low deductibles! and a maximum of NIS 1500 only per surgery (75% off the Clalit Mushlam Gold deductible).