1993 110 the Excavations on the Site of St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

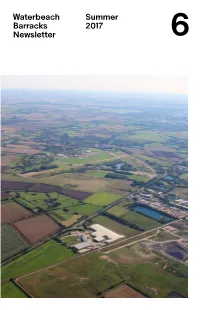

Waterbeach Barracks Newsletter Summer 2017

Waterbeach Summer Barracks 2017 Newsletter 6 Welcome to the sixth community newsletter from Urban&Civic. Urban&Civic is the Development Manager appointed by the Hello Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO) to take forward the development of the former Waterbeach Barracks and Airfield site. In this edition: With the Outline Planning Application submitted in February 2017, and formal consultation events Waterbeach Running Festival 4-5 concluded, the key partners involved are working through a range of follow-up discussions and Summer at the Beach 6-7 technical reviews as part of the planning process. 514 Squadron Reunion 8 While those discussions continue, Urban&Civic is continuing to open up the Barracks for local Planehunters Lancaster 9 use and is building local partnerships to ensure NN775 Excavation the development coming forward maximises local benefits and minimises local impacts. Reopening of the Waterbeach 10-11 Military Heritage Museum In this newsletter we set out the latest on the planning discussions and some of the recent Feature on Denny Abbey and 12-15 community events on site including the Waterbeach The Farmland Museum Running Festival, Summer at the Beach and the reopening of the Waterbeach Military Heritage Cycling Infrastructure 16-17 Museum. We have also been out and about exploring Denny Abbey and the Farmland Museum. Planning update 18-19 We are always happy to meet up with anyone who wants a more detailed discussion of the plans, to come along to speak to local groups or provide a tour of the site or the facilities for hire. Please get in touch with me using the contact details below. -

Parish Clerks

CLERKS OF PARISH COUNCILS ALDINGTON & Mrs T Hale, 9 Celak Close, Aldington, Ashford TN25 7EB Tel: BONNINGTON: email – [email protected] (01233) 721372 APPLEDORE: Mrs M Shaw, The Homestead, Appledore, Ashford TN26 2AJ Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 758298 BETHERSDEN: Mrs M Shaw, The Homestead, Appledore, Ashford TN26 2AJ Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 758298 BIDDENDEN: Mrs A Swannick, 18 Lime Trees, Staplehurst, Tonbridge TN12 0SS Tel: email – [email protected] (01580) 890750 BILSINGTON: Mr P Settlefield, Wealden House, Grand Parade, Littlestone, Tel: New Romney, TN28 8NQ email – [email protected] 07714 300986 BOUGHTON Mr J Matthews (Chairman), Jadeleine, 336 Sandyhurst Lane, Tel: ALUPH & Boughton Aluph, Ashford TN25 4PE (01233) 339220 EASTWELL: email [email protected] BRABOURNE: Mrs S Wood, 14 Sandyhurst Lane, Ashford TN25 4NS Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 623902 BROOK: Mrs T Block, The Briars, The Street, Hastingleigh, Ashford TN25 5HUTel: email – [email protected] (01233) 750415 CHALLOCK: Mrs K Wooltorton, c/o Challock Post Office, The Lees, Challock Tel: Ashford TN25 4BP email – [email protected] (01233) 740351 CHARING: Mrs D Austen, 6 Haffenden Meadow, Charing, Ashford TN27 0JR Tel: email – [email protected] (01233) 713599 CHILHAM: Mr G Dear, Chilham Parish Council, PO Box 983, Canterbury CT1 9EA Tel: email – [email protected] 07923 631596 EGERTON: Mrs H James, Jollis Field, Coldbridge Lane, Egerton, Ashford TN27 9BP Tel: -

Geoffrey Wheeler

Ricardian Bulletin Magazine of the Richard III Society ISSN 0308 4337 March 2012 Ricardian Bulletin March 2012 Contents 2 From the Chairman 3 Society News and Notices 9 Focus on the Visits Committee 14 For Richard and Anne: twin plaques (part 2), by Geoffrey Wheeler 16 Were you at Fotheringhay last December? 18 News and Reviews 25 Media Retrospective 27 The Man Himself: Richard‟s Religious Donations, by Lynda Pidgeon 31 A new adventure of Alianore Audley, by Brian Wainwright 35 Paper from the 2011 Study Weekend: John de la Pole, earl of Lincoln, by David Baldwin 38 The Maulden Boar Badge, by Rose Skuse 40 Katherine Courtenay: Plantagenet princess, Tudor countess (part 2), by Judith Ridley 43 Miracle at Denny Abbey, by Lesley Boatwright 46 Caveat emptor: some recent auction anomalies, by Geoffrey Wheeler 48 The problem of the gaps (from The Art of Biography, by Paul Murray Kendall) 49 The pitfalls of time travelling, by Toni Mount 51 Correspondence 55 The Barton Library 57 Future Society Events 59 Branches and Groups 63 New Members and Recently Deceased Members 64 Calendar Contributions Contributions are welcomed from all members. All contributions should be sent to Lesley Boatwright. Bulletin Press Dates 15 January for March issue; 15 April for June issue; 15 July for September issue; 15 October for December issue. Articles should be sent well in advance. Bulletin & Ricardian Back Numbers Back issues of The Ricardian and the Bulletin are available from Judith Ridley. If you are interested in obtaining any back numbers, please contact Mrs Ridley to establish whether she holds the issue(s) in which you are interested. -

Adopted Wye Neighbourhood Plan 2015-2030

ASHFORD LOCAL PLAN 2030 EXAMINATION LIBRARY GBD09 Ashford Borough Council ADOPTED WYE NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2015-2030 Wye Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015-2030 The Crown, in Wye and Crundale Downs Special Area of Conservation Dedication This document is dedicated to Ian Coulson (1955 - 2015). Ian’s infectious enthusiasm for conserving Wye was shown through his contributions to the Village Design Statement and Village Plan, and more recently in propelling the preparation of the Neighbourhood Plan as chairman of the Neighbourhood Plan Group 2012-15. 2 CONTENTS Page Foreword................................................................................................5 Schedule of policies................................................................................6 1. Preparing the plan 1.1 Purpose ……………………………………………………………………………………………7 1.2 Submitting body ……………………………………………………………………………… 7 1.3 Neighbourhood Area ………………………………………………………………………. 7 1.4 Context …………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 1.5 Plan Period, Monitoring and Review …………………………………………….... 8 1.6 Plan Development Process ……………………………………………………………… 8 1.6.1 Housing Need …………………………………………………………………….. 9 1.6.2 Potential sites ……………………………………………………………………… 9 1.6.3 A picture of life in the village ………………………………………………..9 1.6.4 Design of development and housing …………………………………… 10 1.7 Community engagement ………………………………………………………………..…10 1.7.1 Scenarios and workshops ……………………………………………………..10 1.7.2 Free school survey ………………………………………………………………..11 1.7.3 Public meetings ………………………………………………………………….. -

Chapter 3: Strategic Sites

ChapterChapter 33 StrategicStrategic SitesSites Northstowe Bourn Airfield New Village Waterbeach New Town Cambourne West Proposed Submission South Cambridgeshire Local Plan July 2013 Chapter 3 Strategic Sites Chapter 3 Strategic Sites 3.1 The Spatial Strategy Chapter identifies the objectively assessed housing requirement for 19,000 new homes in the district over the period 2011-2031 and the strategic sites that form a major part of the development strategy in the Local Plan. These are a combination of sites carried forward from the Local Development Framework (2007-2010) and three new sites. Policy S/6 confirms that the Area Action Plans for the following sites remain part of the development plan for the plan period to 2031 or until such time as the developments are complete: Northstowe (except as amended by Policy SS/7 in this chapter) North West Cambridge; Cambridge Southern Fringe; and Cambridge East (except as amended by Policy SS/3 in this chapter). 3.2 This chapter includes polices for the following existing and new strategic allocations for housing, employment and mixed use developments: Edge of Cambridge: Orchard Park – site carried forward from the Site Specific Policies Development Plan Document (DPD) 2010 with updated policy to provide for the completion of the development; Land between Huntingdon Road and Histon Road – the site carried forward from the Site Specific Policies DPD 2010 but extended to the north following the Green Belt review informing the Local Plan. The notional capacity of the sites as extended is -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

Agenda Item 10

AGENDA ITEM NO 10 MAIN CASE Reference No: EXT/00002/18 Proposal: CAMBRIDGESHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL - Erection of an energy from waste facility, air cooled condensers and associated infrastructure, including the development of an internal access road; office/welfare accommodation; workshop; car, cycle and coach parking; perimeter fencing; electricity sub-stations; weighbridges; weighbridge office; water tank; silos; lighting; heat offtake pipe; surface water management system; hardstandings; earthworks; landscaping and bridge crossings Site Address: Waterbeach Waste Management Park Ely Road Landbeach CB25 9PG Applicant: AmeyCespa (East) Limited Case Officer: Andrew Phillips, Senior Planning Officer Date Received: 16 January 2018 Requested 6 February 2018 comments by: [S255] 1.0 RECOMMENDATION 1.1 Members are recommended to confirm the wording of the consultation response of East Cambridgeshire District Council to Cambridgeshire County Council in respect of the above proposal as: Thank you for your consultation on the 16 January 2018 and follow up email on the 24 January 2018. The proposal is allocated in policy (SSP W1K) in Minerals and Waste Site Specific Proposals Development Plan Document Adopted February 2012. However, following the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) being adopted March 2012, the weight granted to this policy should be based on its compliance with the NPPF. It is noted that the Planning Statement makes due reference to the NPPF. Agenda Item 10 – Page 1 It is noted and supported that the County Council Local Planning Authority is hiring relevant specialists to assess this application in relation to noise, emissions and visual impact and East Cambridgeshire support this. It is noted that the electrical and heat connections to offsite infrastructure/development will cause short congestion and delay on the A10. -

General Index

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( 419 ) GENERAL INDEX. • Abberbury, Richd. (1378), 76. Anstie, Eleanor (of Suffolk), 104, 105. Abbod, Hamo, 312. Apilton, Eoger, arms of, 395. Abercorn, lord, 226. Apoldurfeld arms, 396. Abergavenny, lord (1514), 109; (1554), Appledore, 321, 375-6. 143, 231; (1497), 104 ; arms, 106 ; Appulby, Symon, 34. 394; Margaret, dau. of Edward, Apuldre, 312, 375. lord A., 105. Archebaud, Martin, 335, 339, 354. Achard, Beatrix, 324. Archer, Nicholas 1', of Dover, 332. Acrise, 335. Archery practice, 163. Acton, Sir Eoger, 97. Ardrey, Eev. John, 274. Adam, Cristina, 317 ; John, 317, 324. Ariosto, portrait of, 161. Addison, Thomas, 292 ; Mrs., 300. Arlington, lord (Sir Hy. Bennett), 201, Adilda, monacha et anachorita, 26. 277-281. Affright, Stevyn, 410. Armour, 65, 89, 108. Aghemund, Godfrey, 341; John, 341; Arnold, G. M., xxxviii, xl ; on Graves- Mabilia, 341. end in days of old, xlii. Alard, 310; Stephen, 336, 343. Arnold, Eobert, 396. Albemarle, duke of, 258, 261. Arran, Mary countess of, 263, 272. Alcock, John, of Canterbury, 399. Arundel, archbishop, 36, 94. Alday, John, 396. Arundel, earl of, Philip, 231; Henry, Aldgate (London), 360, 363. 231; Thomas, 231, 233, 234,239-241, Aldham, 310; Achardus de, 346; 249. Katherine, 345. Arundel, John de, 355 ; Juliana, 355. Aldinge, 315 [Yalding?]. Arundel House (London), 233. Aldington, 378. Arundel, Friars of, 371. Alee, John, 403. Arundel of Wardour, lady, 222. Aleyn, John, of Ifeld, 311. Ash, 310; next-Sandwich, 23, 306, Aleyne, Godefridus, 330,333; Theobald, 338, 358. 333. -

Phone: 01580 755104 for Advertising Sales

www.northdownsad.co.uk N o r t h D o w [email protected] co.uk Why advertise with North Downs Ad? We are a well-known and trusted name. With 33,300 copies printed every month and online availability, we connect you and your products and services with your ideal customers. MEDIA INFORMATION Print run Cover price Distribution area 33,300 FREE North Kent M20/M2 Royal Mail Available in selected Ad design service Direct to door supermarkets FREE 32,200 in Canterbury and Sittingbourne plus pick Readership Frequency up points across the 83,250* Monthly region * readership based on 2.5 x circulation Phone: 01580 755104 for Advertising Sales North Downs Ad is part of the Wealden Group based at Cowden Close, Horns Road, Hawkhurst, Kent TN18 4QT RNOYAoL rMtAhIL DDISToRIwBUTnIOs N AAREd AS 32,200 copies delivered by Royal Mail plus extensive pick-up points throughout the region. ME9 9 UPLEES 2455 DEERTON STREET OARE GRAVENEY TEYNHAM 3468 GOODNESTONE LUDDENHAM ME13 7 COURT DARGATE RODMERSHAM FAVERSHAM LYNSTED ME13 8 HERNHILL 5177 MILSTEAD BOUGHTON STREET NEWNHAM WHITEHILL FRINSTED ME9 0 DUNKIRK BROAD ME13 9 DODDINGTON STREET WORMSHILL 921 EASTLING SHELDWICH 2390 WICHLING CHARTHAM HOLLINGBOURNE HATCH ME13 0 SELLING EYHORNE STREET BADLESMERE 1350 CT4 8 CHARTHAM LEAVELAND 595 ME17 1 SHOTTENDEN SHALMSFORD LEEDS 2637 HARRIETSHAM STREET LENHAM CHILHAM BROOMFIELD WARREN STALISFIELD GREEN LANGLEY HEATH MOLASH LANGLEY ME17 2 STREET CT4 7 ME17 3 1773 CHALLOCK GODMERSHAM 2467 GRAFTY CHARING 2733 GREEN SUTTON ULCOMBE CRUNDALE CHART VALENCE TN25 4 SUTTON TN27 0 1999 WESTWELL 2364 BOUGHTON LEES WYE LITTLE CHART TN25 5 BROOK 1799 PLUCKLEY HASTINGLEIGH HINXHILL BRABOURNE Black numbers = Postcodes Red numbers = Number of properties receiving North Downs Ad All residents and business properties are covered within the postcode areas. -

Ickleton Draft 2019 Report

Cambridge Archaeology Field Group An archaeological evaluation at Abbey Farm Ickleton South Cambridgeshire NGR TL 4892 4357 ECB 5896 CAFG code IAF2019 Interim report June 2019 1 Summary Little previous archaeological investigation has been done on the site of the Benedictine priory at Ickleton – this is also true for most of the small rural nunneries in England. Previous excavation, prior to conversion of the barns at Abbey Farm to business activities, had shown the possible robbed out footings of a perimeter wall and a more recent geophysical survey has indicated the possibility of an area with substantial buried footings. A single 10x2m trench was excavated in June 2019 by CAFG members to a depth of c0.3m across these features but although mortar indicating the possible line of the perimeter wall was found most of the area excavated had large amount of flint nodules associated with pottery of the 17/18th centuries. One area, to the west of the supposed wall did have contexts which only contained 12/15th pottery, but this was not fully explored. The expectation was that a return to the excavation would be made in June 2020 but due to the pandemic of Corvid-19 this has been delayed. Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Topography and Geology ....................................................................................................................... 1 Archaeological and Historical Background -

6 X 10 Long.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521024579 - Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England Mary C. Erler Index More information Index of manuscripts Page numbers set in italics indicate illustrative material. aberdeen Magdalene College University Library 134 189 n. 8 Pepys 2125, 194 n. 52 St. John’s College brussels A.I.7190–91 n. 23 Bibl. Royale 9272–76 170 n. 55 Bibl. Royale IV. 481 148, 181 n. 26 Trinity College B. 11.4141 B. 14. 15 (301) 156 n. 44, 176 n. 22 cambridge B. 15. 18 (354) 190 n. 18 University Library (CUL) O. 7. 12 149 Addl. 3042 144 Addl. 7220 160 n. 32 Addl. 8335 148 dublin Dd, 5.5167n. 20 Gg.5.24 57 Trinity College Ii.6.40 194 n. 52 Kk.6.39 144 209 169 n. 47 Mm.3.13 143 409 160 n. 33 Corpus Christi College durham 268 35, 149 University Library Cosin Fitzwilliam Museum V.iii.24 76, 176 nn. 22 and 24 V.v.12 148 3–1979 178 n. 54 McClean 132 176 n. 22 edinburgh Gonville and Caius College National Library of Scotland 124/61 145 390/610 175 n. 11 Advocates 18.6.5162n. 59 215 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521024579 - Women, Reading, and Piety in Late Medieval England Mary C. Erler Index More information Index of manuscripts london Guildhall Library British Library (BL) 4424 168 nn. 32 and 41, 169 n. 43, 172 n. 71 9171/2168nn. 32, 33, 38 and 41, 170–71 n. 58 Addl. 5833 186 n. -

BOYS Or BOYES of Godmersham, Kent, England

File name - 202PAF.doc Original - 31 st Oct 2000 Data from - M.D.Boyes files Original source - Variants - BOYS Areas - KEN – Canterbury, Eastry, Egerton, Faversham, Godmersham, Littlebourne, Lynsted, Tonbridge, CAM - Cambridge, Revisions - 15 th Dec 2001 – added RINs 15 – 81 19 th Dec 2001 – numerous corrections and added RINs 82 – 91 3rd Aug 2002 – added RINs 92, 93 – data from JVB 11 th Feb 2003 – added RINs 94, 95 14 th Dec 2003 – added RINs 102 – 121 16 th Feb 2004 – added RINs 125 – 133 5th Feb 2006 – added RINs 138 – 140 30 th Mar 2007 – added RINs 144 – 147 15 th Feb 2008 – added RINs 151 – 154 2nd Apr 2008 – added RINs 155 – 208 when PAF 517 merged into this file 2nd Jan 2009 – added RINs 210 – 213 8th Aug 2009 – added 214 20 th Mar 2010 – added RINs 216 – 220 3rd Aug 2010 - added RINs 229 21 st Oct 2013 – added RINs 232 – 239 (was file 10551) some info from [email protected] 26 th Oct 2013 – added RINs 240 – 241 data from David Boys Notes - RINs 1 – 241 The Godmersham branch 202paf.doc Page 1 of 9 1. 2. Daniel BOYS (16) = Ann (17) = Elizabeth SPRATT (20) bn THEOBALD ? m1 09 Jul 1677 ? Herne Hill ? m2 20 Nov 1690 d 1710 KEN, Canterbury William (25) Ann (26) bn 1699 1690 bp 25 Jan 1700 KEN, Lynsted m Thomas (27) PYE Daniel (15) = Mary (19) Thomas (18) = Sarah FERREL (21) bp 31 May 1685 PAGE 1682 KEN, Lynsted KEN, Lynsted m1 03 Oct 1711 m 1714 KEN, Crundale m2 20 Nov 1690 KEN, Canterbury d d 1736 d 1750 Elizabeth (22) Dinah (23) bn 1718 1715 d 1718 m 17 Mar 1739 James (24) COULTER KEN, Canterbury Nicholas (1) = Sarah OLIVER