Effects of Exposure to Aggressive Bumper Stickers on Driving Behavior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roundup See Page 3 Nasa Manned Spacecraft Center Houston, Texas

COLUMBIA TIMELINE FLY WEDNESDAY ROUNDUP SEE PAGE 3 NASA MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER HOUSTON, TEXAS VO/. 8, NO. 19 JULY 11, 1969 National goal nears fulfillment in Apollo 11 Moonshot "To perform a manned lunar this Wednesday at 9:32 a.m. EDT The mission will be the fifth coast. The "go ahead" for this two revolutions later to 54-bv-66 landing and return." from Kennedy Space Center Pad manned Apollo flight and the injection will follow a complete nautical miles. This is the goal, simply sta_ed, 39-A. third to the Moon. checkout of the spacecraft's read- Both lunar orbit insertion that has existed in the minds of The timeline for Apollo 11 is A powerful Saturn V lift-off iness, burns, using the spacecraft's men for centuries and in the almost identical to its immediate from 39-A on the 16th -,viii be- About a half hour after trans- 20,500-pound-thrust service pro- hearts of Americans for the past predecessor, Apollo i0, which gin the three-day lunar journey, lunar injection, the command pulsion system, will be made be- decade, came within 50,000 feet of lunar About 12 minutes later the service module (call sign, Co- hind the Moon when Apollo 11 But the goal is no longer a soil. the spacecraft is inserted into a lumbia) wilI separate from the is out of contact with Manned fantastic dream. The way has Apollo ll's Prime Crew in- 100-nautical-mile circular Earth Saturn third stage, turn around Space Flight Network stations been paved, we have the ability cludes Nell A. -

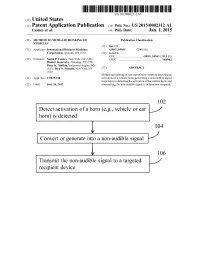

Detect Activation of a Horn (E.G., Vehicle Or Car Transmit the Non

US 2015.0002312A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0002312 A1 Caskey et al. (43) Pub. Date: Jan. 1, 2015 (54) METHOD TO MITIGATE HONKING OF Publication Classification VEHICLES (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: International Business Machines GSGI/0965 (2006.01) Corporation, Armonk, NY (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC .................................... G08G I/0965 (2013.01) (72) Inventors: Sasha P. Caskey, New York, NY (US); USPC .......................................................... 340/902 Dimitri Kanevsky, Ossining, NY (US); Peter K. Malkin, Yorktown Heights, NY (US); Tara N. Sainath, New York, NY (57) ABSTRACT US (US) Mitigating honking, in one aspect, may comprise detecting an (21) Appl. No.: 13/927,338 activation of a vehicle horn, generating a non-audible signal responsive to detecting the activation of the vehicle horn, and (22) Filed: Jun. 26, 2013 transmitting the non-audible signal to at least one recipient. 102 Detect activation of a horn (e.g., vehicle or car horn) is detected 104 Convert or generate into a non-audible signal 106 Transmit the non-audible signal to a targeted recipient device Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2015 Sheet 1 of 4 US 2015/0002312 A1 ['31H Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2015 Sheet 2 of 4 US 2015/0002312 A1 Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2015 Sheet 3 of 4 US 2015/0002312 A1 909 JOSS000Id JOSS000Id Z09) Patent Application Publication Jan. 1, 2015 Sheet 4 of 4 US 2015/0002312 A1 8| <--!> {{OVRIOLS WEILSÅS 8Z ÅRHOVNGIVNI ZZ 9| XVÕIdISICI (S)HOSSROOH? (S),IOVHHALNI (S),IOIA@IGI ZI 9Z US 2015/0002312 A1 Jan. -

CAR TROUBLE a Dark Comedy...About Suicide

CAR TROUBLE A dark comedy...about suicide FADE IN: EXT. WOODS - DAY We open on a middle-aged MAN wearing a business suit as he sits in a gorgeous and immaculately maintained 1970s classic BRITISH CAR which is sitting in the middle of a secluded wooded area. INT. CAR - DAY The man looks despondent as he sits in the car. He’s mentally preparing himself for his mission. After some tense moments he takes his leather bound note pad and pen and scribbles a message on it then places the note pad on the passenger’s seat. He puts both hands on the steering wheel and looks out the windshield, takes a couple of deep breaths to ready himself then opens the door and gets out of the car. EXT. CAR/WOODS - DAY The camera tracks the exterior of the car and finds the man at the trunk. He’s getting out a long garden hose. From the interior of the car we see the hose poke through the window which is only about half way up. Realizing the window needs to be closed more, he reaches into the car and turns the key to the on position. When he presses the switch to raise the window, the window starts to move but stops. He presses the window switch again but the window doesn’t budge. He presses the button a few more times in succession but nothing. MAN Come on, come on. As he presses the switch the window moves again but then stops then starts again then finally stops. -

Decision, and This Appeal Followed

REPORTED IN THE COURT OF SPECIAL APPEALS OF MARYLAND No. 713 SEPTEMBER TERM, 2014 JOHN T. MITCHELL v. MARYLAND MOTOR VEHICLE ADMINISTRATION Eyler, Deborah, S., Arthur, Kenney, James. A., III (Retired, Specially Assigned), JJ. Opinion by Eyler, Deborah, S., J. Filed: November 25, 2015 John T. Mitchell applied to the Maryland Motor Vehicle Administration (“MVA”) for vanity plates bearing the letters MIERDA. The application was granted. Two years later, the MVA received a complaint from a member of the public about Mitchell’s vanity plates. It investigated and determined that “mierda” is the Spanish word for “shit.” Pursuant to a State regulation giving the MVA discretion to deny or rescind vanity plates that contain profanities, epithets, or obscenities, the MVA rescinded Mitchell’s vanity plates. Mitchell challenged the MVA’s action in a contested case hearing before an Administrative Law Judge (“ALJ”). The ALJ decided that the MVA properly exercised its discretion to rescind Mitchell’s vanity plates and that its action did not violate Mitchell’s First Amendment right to free speech. The Circuit Court for Prince George’s County upheld the decision, and this appeal followed. The novel issues before this Court are whether messages on vanity plates are government speech or private speech on government property; and if they are the latter, what degree of government restriction may be imposed on that private speech under the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.1 We hold that Mitchell’s vanity plate message is private speech on government property, not government speech. Under prevailing United States Supreme Court jurisprudence, Maryland vanity plates are a “nonpublic forum,” in which government restrictions on private speech will pass muster 1 The First Amendment to the United States Constitution applies to the States through the Fourteenth Amendment. -

Bumper Stickers, Driver-Cars and the Spaces of Social Encounter on Contemporary American Superhighways

Interstate Interstitials: Bumper Stickers, Driver-Cars and the Spaces of Social Encounter on Contemporary American Superhighways Walter Goettlich A Thesis in The Department of Sociology and Anthropology Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Sociology) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada April 2015 © Walter Goettlich, 2015 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Walter Goettlich Entitled: Interstate Interstitials: Bumper Stickers, Driver-Cars and the Spaces of Social Encounter on Contemporary American Superhighways and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Meir Amor, PhD Chair Katja Neves, PhD Examiner Daniel Dagenais, PhD Examiner Bart Simon, PhD Supervisor Approved by: Greg Nielsen, PhD Chair of Department André Roy, PhD Dean of Faculty of Arts and Sciences Date: April 15, 2015 Abstract Since the turn of the 21st century, it has been the established aim of mobilities scholars to investigate the ways in which contemporary life is conditioned and carried out through the movements of people, things and ideas. Despite concerns over global climate change on the one hand, and the heyday of peak-oil receding quickly into the rear view mirror on the other, the primary vehicle of mobility in the United States remains the personal automobile. Contemporary American notions of self and identity are frequently interpreted through the individual’s relationship(s) to cars and driving, and while cars themselves are mass-manufactured items, they afford a number of many non-technical practices of customization as modes of individuation. -

2020 Kia Sportage Owner's Manual

Kia, THE COMPANY Thank you for becoming the owner of a new Kia vehicle. As a global car manufacturer focused on building high-quality vehi- cles with exceptional value, Kia Motors is dedicated to providing you with a customer service experience that exceeds your expectations. All information contained in this Owner’s Manual was accurate at the time of publication. However, Kia reserves the right to make changes at any time so that our policy of continual product improvement can be carried out. This manual applies to all trims of this vehicle and includes images, descriptions, and explanations of optional as well as standard equip- ment. As a result, some material in this manual may not be applicable to your specific Kia vehicle. Some images are shown for illustration only and may show features that differ from those on your vehicle. Drive safely and enjoy your Kia! Foreword Thank you for choosing a Kia vehicle. The information and specifications provided in this manual When you require service, remember that your Kia dealer were accurate at the time of printing. Kia reserves the right to knows your vehicle best. Your dealer has factory-trained tech- discontinue or change specifications or design at any time nicians, recommended special tools and genuine Kia replace- without notice and without incurring any obligation. If you ment parts. It is dedicated to your complete customer satisfac- have questions, always check with your Kia dealer. tion. We assure you of our continuing interest in your motoring Because subsequent owners require this important information pleasure and satisfaction in your Kia vehicle. -

Automobility And'my Family'stickers

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Doyle, Kylie & Tranter, Kieran (2015) Automobility and ’My Family’ stickers. Continuum, 29(1), pp. 70-83. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/124807/ c Consult author(s) regarding copyright matters This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2014.968524 This is a preprint version of: Kylie Doyle and Kieran Tranter ‘Automobility and “My Family” Stickers’ (2015) 29(1) Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 70-83 DOI: 10.1080/10304312.2014.968524. -

Demonstration and Evaluation of the Heed the Speed Pedestrian Safety Program

DOT HS 811 515 July 2012 Demonstration and Evaluation of the Heed the Speed Pedestrian Safety Program Final Report DISCLAIMER This publication is distributed by the U.S. Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in the interest of information exchange. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Transportation or the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. If trade names, manufacturers’ names, or specific products are mentioned, it is because they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Suggested APA Citation: Blomberg, R. D., Thomas III, F. D., & Marziani, B. J. (2012, July). Demonstration and Evaluation of the Heed the Speed Pedestrian Safety Program (Report No. DOT HS 811 515). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. DOT HS 811 515 4. Title and Subject 5. Report Date July 2012 Demonstration and Evaluation of the Heed the Speed Pedestrian Safety Program 6. Performing Organization Code 216 7. Authors 8. Performing Organization Report No. Richard D. Blomberg, F. Dennis Thomas, III, and Bruce J. Marziani 216-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Dunlap and Associates, Inc. 110 Lenox Avenue 11. Contract or Grant No. Stamford, CT 06906 DTNH22-05-C-05088 12. -

This Kind of Thing Happens All the Time Ashley Melchiore Honors College, Pace University

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Honors College Theses Pforzheimer Honors College 1-1-2014 This Kind of Thing Happens All the Time Ashley MelChiore Honors College, Pace University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation MelChiore, Ashley, "This Kind of Thing Happens All the Time" (2014). Honors College Theses. Paper 129. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/honorscollege_theses/129 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pforzheimer Honors College at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. That Kind of Thing Happens All the Time Ashley Melchiorre 18 December 2013 English –concentration in Writing and Literature Professor Oseye English Introduction My original mission for this project was to write several short stories which would revolve around different types of young characters living in New York and focus on the types of struggles and moments of weakness that people face day to day that can frequently, go overlooked or remain under the radar. Originally I had titled this, Different Kinds of Dirty because of the shame and humiliation these characters constantly face, however after I was finished I realized that my true focus wasn’t to highlight their pain, but rather, how often these things happen, and despite how detrimental these experiences can be to a young adults development and growth into an adult, these incidences frequently go unspoken of unless it’s between close and friends and family; which is why I gave my characters colloquial voices. -

Oregonians Stand out Pedestrian Safety Toolkit | Logos

OREGONIANS STAND OUT PEDESTRIAN SAFETY TOOLKIT | LOGOS BLACK & WHITE FULL COLOR Color Logo EMBLEM For more resources and information on the pedestrian and bicycle safety program, please visit oregonwalkbike.org Emblem Logo OREGONIANS STAND OUT PEDESTRIAN SAFETY TOOLKIT | POSTER, FLYER & RACK CARD DAY... NIGHT... BRIGHT! DAY... NIGHT... BRIGHT! OVER FOR PEDESTRIAN SAFETY TIPS 3.7x8.5” Rack Card Rack Card 3.7x8.5 8.5x11” Flyer Flyer 8.5x11 All shown at 50% actual size 11x17” Poster Poster 11x17 OREGONIANS STAND OUT PEDESTRIAN SAFETY TOOLKIT | POSTCARDS ON FOOT AND ON WHEELS, LET,S ALL BE CROSSWALK BRIGHT AT NIGHT! CROSS TRAINING FOR DRIVERS- AND PEDESTRIANS Most crashes where a pedestrian is killed happen at dusk or at night, when it’s harder to see. So while driving, it’s important to… MARKED CROSSWALK MID-BLOCK CROSSWALK UNMARKED CROSSWALK Be extra vigilant at dusk. As the sun is going down, it’s even harder to see pedestrians from behind the wheel. So keep your eyes peeled. Expect pedestrians at corners and mid-block crosswalks. Be ready to stop. Slow down and keep scanning the road in front of you. Watch for moving shapes in the dark. WHEN TURNING AT A TRAFFIC SIGNAL: STOP AND REMAIN STOPPED UNTIL PEDESTRIANS HAVE CLEARED THE LANE YOU ARE TURNING INTO, Front PLUS AT LEAST SIX FEET OF THE NEXT LANE. Front DAY... NIGHT... BRIGHT! HEADS WHILE DRIVING... UP STEER CLEAR Never pass a stopped vehicle at a OF DISTRACTIONS AT ALL TIMES! crosswalk. Pedestrians may be crossing. On a multi-lane road, try to stop 30 feet before the LET,S ALL LOOK OUT FOR EACH OTHER! crosswalk to improve visibility. -

Cranford Police Department Pace Car Program

Cranford Police Who to Contact Keep Kids Alive Drive 25® Department If you would like to expand your traffic For more information about the Pace Car calming efforts in your own neighborhood Pace Car Program, contact any member of the Traffic Division at please consider taking part in our Keep Program 908-272-2222. Kids Alive Drive 25® (KKAD25) program. Cranford residents can request a free lawn Mail or drop off your completed sign with the KKAD25 logo to install on their Pace Car Pledge form to: front lawn when their children are out playing Cranford Police Department in order to further remind motorists of the A Traffic Calming Traffic Division need to drive within the posted speed limit. Program of the Cranford 8 Springfield Avenue Cranford, NJ 07016 When motorists see the KKAD25 logo it is a Police Department reminder to them to check their speed and Fax or e-mail: slow down as needed. You can also fax your form to the Traffic Division at 908-709-7332 Also, any neighborhood or township or e-mail the pledge form to organization can request a presentation by a [email protected] member of the Traffic Division on Keep Kids Alive Drive 25®, bicycle safety, pedestrian Once we receive your signed safety, or graduated drivers licenses. pledge we will mail you your choice of a Keep Kids Alive Drive 25® vehicle magnet or a Keep Kids Through a comprehensive traffic safety plan Alive Drive 25® bumper sticker. we can all make our roads a safer place for our families, friends, and neighbors. -

Gibson1 Bumper Stickers and Helping Based on Impression Formation

Gibson1 Bumper Stickers and Helping Based on Impression Formation Cassidy Gibson Milligan College Gibson 2 Abstract A well-established tenet of social psychology is that our first impressions matter, and those impressions are often formed using minimal information, such as attractiveness, complexion, and mannerism (Carlston & Schneid, 2015, 95). One area that has not been investigated to date, however, is bumper stickers. In this naturalistic field experiment, we explored the relationship between bumper stickers and helping behavior. Based on previous studies of impression formation, we predicted that the presence of offensive bumper stickers would reduce the amount of help offered to a stranger. Sixty adults entering a large shopping center in Northeast Tennessee were approached at random and asked for directions to a nearby nature center. Subjects were approached by a 20 year old white female standing in front of a parked car covered with 7 hostile bumper stickers (e.g., “Watch out for the idiot behind me”) or the same car covered with 7 neutral bumper stickers (e.g., “Blessed Be”). A total of 30 adults were approached for each condition (neutral vs. hostile stickers) over the course of 6 separate days. A female confederate posing as a seated passenger unobtrusively recorded the following for each encounter: (a) level of detail in the directions given, (b) disposition of the subject, and (c) approximate distance between experimenter and subject. This confederate was unaware of the type of stickers on the car during each encounter and was, thus, blind to the conditions. The stickers were periodically changed throughout the experiment. Statistically significant differences were found for all three dependent variables.