Speaking Truth to Power by Jedeit J. Riek And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Porno Bingo Instructions

Porno Bingo Instructions Host Instructions: · Decide when to start and select your goal(s) · Designate a judge to announce events · Cross off events from the list below when announced Goals: · First to get any line (up, down, left, right, diagonally) · First to get any 2 lines · First to get the four corners · First to get two diagonal lines through the middle (an "X") · First to get all squares (a "coverall") Guest Instructions: · Check off events on your card as the judge announces them · If you satisfy a goal, announce "BINGO!". You've won! · The judge decides in the case of disputes This is an alphabetical list of all 24 events: Battleground, Brie Bella, Brock Lesnar, Cameron, Daniel Bryan, Dolph Ziggler, El Torito, Elimination Chamber, Extreme Rules, Hell in a Cell, John Cena, Kane, Money in the Bank, Naomi, Natalya, Night of Champions, Nikki Bella, Payback, Roman Reigns, Royal Rumble, Stephanie McMahon, SummerSlam, TLC, Wrestlemania. BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved Porno Bingo Call Sheet This is a randomized list of all 24 bingo events in square format that you can mark off in order, choose from randomly, or cut up to pull from a hat: Nikki Brock Night of Naomi El Torito Bella Lesnar Champions Royal Extreme Hell in Kane Brie Bella Rumble Rules a Cell Money Stephanie Daniel in the Payback Battleground McMahon Bryan Bank Dolph John TLC Wrestlemania Natalya Ziggler Cena Elimination Roman SummerSlam Cameron Chamber Reigns BuzzBuzzBingo.com · Create, Download, Print, Play, BINGO! · Copyright © 2003-2021 · All rights reserved B I N G O Daniel Roman El Torito Kane TLC Bryan Reigns Stephanie John Brock Wrestlemania Payback McMahon Cena Lesnar Night of Elimination FREE Naomi Brie Bella Champions Chamber Money Dolph Hell in Royal in the Battleground Ziggler a Cell Rumble Bank Extreme Nikki Cameron SummerSlam Natalya Rules Bella This bingo card was created randomly from a total of 24 events. -

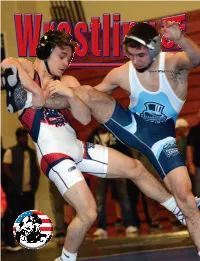

NCAA Wrestling Championships

Editor-In-Chief LANNY BRYANT Order of Merit WRESTLING USA MAGAZINE National Wrestling Hall of Fame AAU National Wrestling Hall of Fame LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Managing Editor CODY BRYANT 2017 Wrestling USA Magazine All-American Teams Assistant Editor By Dan Fickel, National Editor ANN BRYANT National Editor ne of our favorite features of the year is the annual Wrestling USA Magazine’s All- DAN FICKEL American Teams. Each year we are proud to recognize the top high school seniors in National Photographer the country. There are 13 “Dream Teamers”, 13 “Academic Teamers”, 96 other All- G WYATT SCHULTZ Americans, and 120 Honorable Mention All-American selections. Forty-nine states are Contributing Editor represented from the numerous nominations received. BILL WELKER The 2017 Dream Team is a tremendously decorated one, comprised of four-time state Ochampions Daton Fix (132) of Oklahoma, Vito Arujau (138) of New York, Yianni Diakomihalis (145) Design & Art Director CODY BRYANT of New York, and Brady Berge (160) of Minnesota, three-time state champions Spencer Lee (126) of Administrative Assistants Pennsylvania, Cameron Coy (152) of Pennsylvania, Louie DePrez (182) of New York, Jacob Warner LANANN BRYANT (195) of Illinois, and Trent Hillger (285) of Michigan, two-time state champions Joey Harrison (113) of CODI JEAN BRYANT Nebraska, Michael McGee (120) of Illinois, and Michael Labriola (170) of Pennsylvania, and two-time SHANNON (BRYANT) WOLFE National Prep champion Chase Singletary (220) of New Jersey. Singletary also won two state titles in GINGER FLOWERS Florida while in seventh and eighth grade. The 13 members of the team represent 41 state or nation- Advertising/Promotion al prep titles and 2,511 match victories. -

British Bulldogs, Behind SIGNATURE MOVE: F5 Rolled Into One Mass of Humanity

MEMBERS: David Heath (formerly known as Gangrel) BRODUS THE BROOD Edge & Christian, Matt & Jeff Hardy B BRITISH CLAY In 1998, a mystical force appeared in World Wrestling B HT: 6’7” WT: 375 lbs. Entertainment. Led by the David Heath, known in FROM: Planet Funk WWE as Gangrel, Edge & Christian BULLDOGS SIGNATURE MOVE: What the Funk? often entered into WWE events rising from underground surrounded by a circle of ames. They 1960 MEMBERS: Davey Boy Smith, Dynamite Kid As the only living, breathing, rompin’, crept to the ring as their leader sipped blood from his - COMBINED WT: 471 lbs. FROM: England stompin’, Funkasaurus in captivity, chalice and spit it out at the crowd. They often Brodus Clay brings a dangerous participated in bizarre rituals, intimidating and combination of domination and funk -69 frightening the weak. 2010 TITLE HISTORY with him each time he enters the ring. WORLD TAG TEAM Defeated Brutus Beefcake & Greg With the beautiful Naomi and Cameron Opponents were viewed as enemies from another CHAMPIONS Valentine on April 7, 1986 dancing at the big man’s side, it’s nearly world and often victims to their bloodbaths, which impossible not to smile when Clay occurred when the lights in the arena went out and a ▲ ▲ Behind the perfect combination of speed and power, the British makes his way to the ring. red light appeared. When the light came back the Bulldogs became one of the most popular tag teams of their time. victim was laying in the ring covered in blood. In early Clay’s opponents, however, have very Originally competing in promotions throughout Canada and Japan, 1999, they joined Undertaker’s Ministry of Darkness. -

WWE: Redefining Orking-Classw Womanhood Through Commodified Eminismf

Wright State University CORE Scholar The University Honors Program Academic Affairs 4-24-2018 WWE: Redefining orking-ClassW Womanhood through Commodified eminismF Janice M. Sikon Wright State University - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/honors Part of the Women's Studies Commons Repository Citation Sikon, J. M. (2018). WWE: Redefining orking-ClassW Womanhood through Commodified Feminism. Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Affairs at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University Honors Program by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WWE: Redefining Working-Class Womanhood 1 WWE: Redefining Working-Class Womanhood through Commodified Feminism Janice M. Sikon Wright State University WWE: Redefining Working-Class Womanhood 2 Introduction World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) is the largest professional wrestling promotion in the world (Bajaj & Banerjee, 2016). Their programs air in 20 languages in over 180 countries, and in the United States approximately 11 million people watch their programs each week (“FAQ,” n.d.). These programs include six hours of televised weekly events and 16 annual pay- per-view events (“WWE Reports,” 2017). In the first quarter of 2017 the company grossed $188.4 million (“WWE Reports,” 2017). They have close ties with the current presidential administration, as Small Business Administrator Linda McMahon was the CEO of the company from 1980 to 2009 (Reuters, 2009) and President Trump has made several appearances on WWE programming in the past (“Donald Trump,” n.d.). -

Lawler WWE 104 Akira Tozawa Raw 105 Alicia

BASE BASE CARDS 101 Tyler Bate WWE 102 Brie Bella WWE 103 Jerry "The King" Lawler WWE 104 Akira Tozawa Raw 105 Alicia Fox Raw 106 Apollo Crews Raw 107 Ariya Daivari Raw 108 Harley Race WWE Legend 109 Big Show Raw 110 Bo Dallas Raw 111 Braun Strowman Raw 112 Bray Wyatt Raw 113 Cesaro Raw 114 Charly Caruso Raw 115 Curt Hawkins Raw 116 Curtis Axel Raw 117 Dana Brooke Raw 118 Darren Young Raw 119 Dean Ambrose Raw 120 Emma Raw 121 Jeff Hardy Raw 122 Goldust Raw 123 Heath Slater Raw 124 JoJo Raw 125 Kalisto Raw 126 Kurt Angle Raw 127 Mark Henry Raw 128 Matt Hardy Raw 129 Mickie James Raw 130 Neville Raw 131 R-Truth Raw 132 Rhyno Raw 133 Roman Reigns Raw 134 Sasha Banks Raw 135 Seth Rollins Raw 136 Sheamus Raw 137 Summer Rae Raw 138 Aiden English SmackDown LIVE 139 Baron Corbin SmackDown LIVE 140 Becky Lynch SmackDown LIVE 141 Charlotte Flair SmackDown LIVE 142 Daniel Bryan SmackDown LIVE 143 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown LIVE 144 Epico SmackDown LIVE 145 Erick Rowan SmackDown LIVE 146 Fandango SmackDown LIVE 147 James Ellsworth SmackDown LIVE 148 Jey Uso SmackDown LIVE 149 Jimmy Uso SmackDown LIVE 150 Jinder Mahal SmackDown LIVE 151 Kevin Owens SmackDown LIVE 152 Konnor SmackDown LIVE 153 Lana SmackDown LIVE 154 Naomi SmackDown LIVE 155 Natalya SmackDown LIVE 156 Nikki Bella SmackDown LIVE 157 Primo SmackDown LIVE 158 Rusev SmackDown LIVE 159 Sami Zayn SmackDown LIVE 160 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown LIVE 161 Sin Cara SmackDown LIVE 162 Tyler Breeze SmackDown LIVE 163 Viktor SmackDown LIVE 164 Akam NXT 165 Aleister Black NXT 166 Andrade "Cien" Almas -

How Women Fans of World Wrestling Entertainment Perceive Women Wrestlers Melissa Jacobs Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2017 "They've Come to Draw Blood" - How Women Fans of World Wrestling Entertainment Perceive Women Wrestlers Melissa Jacobs Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Jacobs, Melissa, ""They've Come to Draw Blood" - How Women Fans of World Wrestling Entertainment Perceive Women Wrestlers" (2017). All Theses. 2638. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2638 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THEY’VE COME TO DRAW BLOOD” – HOW WOMEN FANS OF WORLD WRESTLING ENTERTAINMENT PERCEIVE WOMEN WRESTLERS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Communication, Technology, and Society by Melissa Jacobs May 2017 Accepted by: Dr. D. Travers Scott, Committee Chair Dr. Erin Ash Dr. Darren Linvill ABSTRACT For a long time, professional wrestling has existed on the outskirts of society, with the idea that it was just for college-aged men. With the rise of the popularity of the World Wrestling Entertainment promotion, professional wrestling entered the mainstream. Celebrities often appear at wrestling shows, and the WWE often hires mainstream musical artists to perform at their biggest shows, WrestleMania and Summer Slam. Despite this still-growing popularity, there still exists a gap between men’s wrestling and women’s wrestling. Often the women aren’t allowed long match times, and for the longest time sometimes weren’t even on the main shows. -

2020 WWE Undisputed Checklist

BASE SUPERSTAR ROSTER 1 Aleister Black Raw 2 Andrade Raw 3 Asuka Raw 4 Becky Lynch Raw 5 Bianca Belair Raw 6 Bobby Lashley Raw 7 Buddy Murphy Raw 8 Charlotte Flair Raw 9 Drew McIntyre Raw 10 Edge Raw 11 Erik Raw 12 Humberto Carrillo Raw 13 Ivar Raw 14 Kairi Sane Raw 15 Kevin Owens Raw 16 Lana Raw 17 Nia Jax Raw 18 Randy Orton Raw 19 Ricochet Raw 20 Ruby Riott Raw 21 R-Truth Raw 22 Samoa Joe Raw 23 Seth Rollins Raw 24 Zelina Vega Raw 25 AJ Styles SmackDown 26 Alexa Bliss SmackDown 27 Bayley SmackDown 28 Big E SmackDown 29 Braun Strowman SmackDown 30 "The Fiend" Bray Wyatt SmackDown 31 Carmella SmackDown 32 Cesaro SmackDown 33 Dana Brooke SmackDown 34 Daniel Bryan SmackDown 35 Dolph Ziggler SmackDown 36 Elias SmackDown 37 King Corbin SmackDown 38 Kofi Kingston SmackDown 39 Lacey Evans SmackDown 40 Matt Riddle SmackDown 41 Mustafa Ali SmackDown 42 Naomi SmackDown 43 Nikki Cross SmackDown 44 Robert Roode SmackDown 45 Roman Reigns SmackDown 46 Sami Zayn SmackDown 47 Sasha Banks SmackDown 48 Sheamus SmackDown 49 Shinsuke Nakamura SmackDown 50 The Miz SmackDown 51 Xavier Woods SmackDown 52 Adam Cole NXT 53 Bobby Fish NXT 54 Candice LeRae NXT 55 Dakota Kai NXT 56 Damian Priest NXT 57 Dominik Dijakovic NXT 58 Finn Bálor NXT 59 Io Shirai NXT 60 Johnny Gargano NXT 61 Kay Lee Ray NXT UK 62 Karrion Kross NXT 63 Keith Lee NXT 64 Kushida NXT 65 Kyle O'Reilly NXT 66 Mia Yim NXT 67 Pete Dunne NXT UK 68 Rhea Ripley NXT 69 Roderick Strong NXT 70 Scarlett NXT 71 Shayna Baszler NXT 72 Tommaso Ciampa NXT 73 Toni Storm NXT UK 74 Velveteen Dream NXT 75 WALTER NXT UK 76 John Cena WWE 77 Ronda Rousey WWE 78 Undertaker WWE 79 Batista Legends 80 Booker T Legends 81 Bret "Hit Man" Hart Legends 82 Diesel Legends 83 Howard Finkel Legends 84 Hulk Hogan Legends 85 Lita Legends 86 Mr. -

The Encounter of Neoliberalism and Popular Feminism in WWE 24: Women’S Evolution

University of Huddersfield Repository Litherland, Benjamin and Wood, Rachel Critical Feminist Hope: The Encounter of Neoliberalism and Popular Feminism in WWE 24: Women’s Evolution Original Citation Litherland, Benjamin and Wood, Rachel (2017) Critical Feminist Hope: The Encounter of Neoliberalism and Popular Feminism in WWE 24: Women’s Evolution. Feminist Media Studies. ISSN 1468-0777 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/32806/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Critical feminist hope: the encounter of neoliberalism and popular feminism in WWE 24: women’s evolution Rachel Wood a* and Benjamin Litherland b a Department of Psychology, Sociology and Politics, Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK; b Centre for Participatory Culture, University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, UK * Contact Rachel Wood [email protected] @Racwood; ORCID: 0000-0002-0053-2969 @DrBenLitherland, ORCID: 0000-0003-3735-354X Biographical Notes Rachel Wood is a research associate in the Department of Psychology, Sociology & Politics at Sheffield Hallam University. -

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Asuka 2 Bobby Roode 3 Ember Moon 4 Eric

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Asuka 2 Bobby Roode 3 Ember Moon 4 Eric Young 5 Hideo Itami 6 Johnny Gargano 7 Liv Morgan 8 Tommaso Ciampa 9 The Rock 10 Alicia Fox 11 Austin Aries 12 Bayley 13 Big Cass 14 Big E 15 Bob Backlund 16 The Brian Kendrick 17 Brock Lesnar 18 Cesaro 19 Charlotte Flair 20 Chris Jericho 21 Enzo Amore 22 Finn Bálor 23 Goldberg 24 Karl Anderson 25 Kevin Owens 26 Kofi Kingston 27 Lana 28 Luke Gallows 29 Mick Foley 30 Roman Reigns 31 Rusev 32 Sami Zayn 33 Samoa Joe 34 Sasha Banks 35 Seth Rollins 36 Sheamus 37 Triple H 38 Xavier Woods 39 AJ Styles 40 Alexa Bliss 41 Baron Corbin 42 Becky Lynch 43 Bray Wyatt 44 Carmella 45 Chad Gable 46 Daniel Bryan 47 Dean Ambrose 48 Dolph Ziggler 49 Heath Slater 50 Jason Jordan 51 Jey Uso 52 Jimmy Uso 53 John Cena 54 Kalisto 55 Kane 56 Luke Harper 57 Maryse 58 The Miz 59 Mojo Rawley 60 Naomi 61 Natalya 62 Nikki Bella 63 Randy Orton 64 Rhyno 65 Shinsuke Nakamura 66 Undertaker 67 Zack Ryder 68 Alundra Blayze 69 Andre the Giant 70 Batista 71 Bret "Hit Man" Hart 72 British Bulldog 73 Brutus "The Barber" Beefcake 74 Diamond Dallas Page 75 Dusty Rhodes 76 Edge 77 Fit Finlay 78 Jake "The Snake" Roberts 79 Jim "The Anvil" Neidhart 80 Ken Shamrock 81 Kevin Nash 82 Lex Luger 83 Terri Runnels 84 "Macho Man" Randy Savage 85 "Million Dollar Man" Ted DiBiase 86 Mr. Perfect 87 "Ravishing" Rick Rude 88 Ric Flair 89 Rob Van Dam 90 Ron Simmons 91 Rowdy Roddy Piper 92 Scott Hall 93 Sgt. -

2019 Topps WWE Women's Division

BASE ROSTER 1 Alexa Bliss RAW® 2 Alicia Fox RAW® 3 Bayley SmackDown® 4 Dana Brooke RAW® 5 Ember Moon SmackDown® 6 Lacey Evans Rookie RAW® 7 Liv Morgan SmackDown® 8 Mickie James SmackDown® 9 Natalya RAW® 10 Nia Jax RAW® 11 Ronda Rousey RAW® 12 Ruby Riott RAW® 13 Sarah Logan RAW® 14 Sasha Banks RAW® 15 Tamina RAW® 16 Renee Young RAW® 17 Stephanie McMahon WWE 18 Maria Kanellis 205 Live® 19 Asuka SmackDown® 20 Becky Lynch SmackDown® 21 Billie Kay SmackDown® 22 Carmella SmackDown® 23 Mandy Rose SmackDown® 24 Maryse WWE 25 Naomi RAW® 26 Nikki Cross Rookie RAW® 27 Peyton Royce SmackDown® 28 Sonya Deville SmackDown® 29 Zelina Vega SmackDown® 30 Paige SmackDown® 31 Aliyah NXT® 32 Bianca Belair NXT® 33 Candice LeRae NXT® 34 Chelsea Green NXT® 35 Dakota Kai NXT® 36 Deonna Purrazzo NXT® 37 Io Shirai NXT® 38 Jessamyn Duke NXT® 39 Jessi Kamea NXT® 40 Kacy Catanzaro NXT® 41 Kairi Sane Rookie SmackDown® 42 Lacey Lane NXT® 43 Marina Shafir NXT® 44 Mia Yim NXT® 45 MJ Jenkins NXT® 46 Shayna Baszler NXT® 47 Taynara Conti NXT® 48 Vanessa Borne NXT® 49 Xia Li NXT® 50 Toni Storm NXT UK® 51 Nina Samuels NXT UK® 52 Alundra Blayze WWE Legend 53 Beth Phoenix WWE Legend 54 Eve Torres WWE Legend 55 Marlena WWE Legend 56 Lita WWE Legend 57 Sherri Martel WWE Legend 58 Miss Elizabeth WWE Legend 59 Trish Stratus WWE Legend 60 Wendi Richter WWE Legend MEMORABLE MATCHES AND MOMENTS 61 Asuka™ def. Alexa Bliss™ Raw® 1/1/2018 Raw® 62 NXT® Women's Champion Ember Moon™ def. -

2019 Topps WWE Smackdown

BASE BASE CARDS 1 Aiden English WWE 2 Aleister Black WWE ROOKIE 3 Ali WWE 4 Andrade WWE 5 Apollo Crews WWE 6 Asuka WWE 7 Bayley WWE 8 Becky Lynch WWE 9 Big E WWE 10 Billie Kay WWE 11 Bo Dallas WWE 12 Buddy Murphy WWE 13 Byron Saxton WWE 14 Carmella WWE 15 Cesaro WWE 16 Chad Gable WWE 17 Charlotte Flair WWE 18 Corey Graves WWE 19 Curtis Axel WWE 20 Daniel Bryan WWE 21 Elias WWE 22 Ember Moon WWE 23 Finn Bálor WWE 24 Greg Hamilton WWE 25 Jeff Hardy WWE 26 Jinder Mahal WWE 27 Kairi Sane WWE ROOKIE 28 Kevin Owens WWE 29 Kofi Kingston WWE 30 Lana WWE 31 Lars Sullivan WWE ROOKIE 32 Liv Morgan WWE 33 Mandy Rose WWE 34 Maryse WWE 35 Matt Hardy WWE 36 Mickie James WWE 37 Otis WWE ROOKIE 38 Paige WWE 39 Peyton Royce WWE 40 R-Truth WWE 41 Randy Orton WWE 42 Roman Reigns WWE 43 Rowan WWE 44 Rusev WWE 45 Samir Singh WWE 46 Sarah Schreiber WWE ROOKIE 47 Sheamus WWE 48 Shelton Benjamin WWE 49 Shinsuke Nakamura WWE 50 Sin Cara WWE 51 Sonya Deville WWE 52 Sunil Singh WWE 53 Tom Phillips WWE 54 Tucker WWE ROOKIE 55 Xavier Woods WWE 56 Zelina Vega WWE 57 Big Show WWE 58 The Rock WWE 59 Triple H WWE Legend 60 Undertaker WWE 61 Albert WWE Legend 62 Beth Phoenix WWE Legend 63 Big Boss Man WWE Legend 64 The British Bulldog WWE Legend 65 Boogeyman WWE Legend 66 King Booker WWE Legend 67 Cactus Jack WWE Legend 68 Christian WWE Legend 69 Chyna WWE Legend 70 "Cowboy" Bob Orton WWE Legend 71 D-Lo Brown WWE Legend 72 Diamond Dallas Page WWE Legend 73 Eddie Guerrero WWE Legend 74 Faarooq WWE Legend 75 Finlay WWE Legend 76 The Godfather WWE Legend 77 Goldberg WWE Legend -

2019 Topps WWE Transcendent Collection

AUTOGRAPH ON CARD AUTOGRAPHS A-AB Alexa Bliss WWE A-AC Adam Cole NXT A-AJ AJ Styles WWE A-AL Aleister Black NXT A-AS Asuka WWE A-BB Brie Bella WWE A-BE Becky Lynch WWE A-BH Bret "Hit Man" Hart WWE Legends A-BK Billie Kay WWE A-BL Brock Lesnar WWE A-BO Bobby Lashley WWE A-BR Bobby Roode WWE A-BS Braun Strowman WWE A-BY Bayley WWE A-CA Carmella WWE A-CF Charlotte Flair WWE A-CJ Chris Jericho WWE A-DA Dean Ambrose WWE A-DB Daniel Bryan WWE A-EL Elias WWE A-FB Finn Balor WWE A-JC John Cena WWE A-JG Johnny Gargano NXT A-KO Kevin Owens WWE A-LL Lex Luger WWE Legends A-LV Liv Morgan WWE A-MA Maryse WWE A-MJ Mickie James WWE A-MM Mr. McMahon WWE A-MR Mandy Rose WWE A-NA Naomi WWE A-NB Nikki Bella WWE A-NT Natalya WWE A-PG Paige WWE A-PR Peyton Royce WWE A-RD Ricky "The Dragon" SteamboatWWE Legends A-RO Randy Orton WWE A-RRR Ronda Rousey WWE A-SA Stone Cold Steve Austin WWE Legends A-SB Sasha Banks WWE A-SH Shane McMahon WWE A-SJ Samoa Joe WWE A-SM Stephanie McMahon WWE A-SN Shinsuke Nakamura WWE A-SR Seth Rollins WWE A-ST Sting WWE Legends A-SW Shawn Michaels WWE Legends A-TH Triple H WWE A-TS Trish Stratus WWE Legends A-UN Undertaker WWE AUTOGRAPHED SKETCH CARD 1 Adam Cole WWE 2 AJ Styles WWE 3 Aleister Black WWE 4 Alexa Bliss WWE 5 Asuka WWE 6 Bayley WWE 7 Becky Lynch WWE 8 Billie Kay WWE 9 Bobby Lashley WWE 10 Bobby Roode WWE 11 Braun Strowman WWE 12 Bray Wyatt WWE 13 Bret Hart WWE 14 Brie Bella WWE 15 Charlotte Flair WWE 16 Daniel Bryan WWE 17 Dean Ambrose WWE 18 Dolph Ziggler WWE 19 Drew McIntyre WWE 20 Elias WWE 21 Ember Moon WWE 22 Finn