Dwarf Woolly-Heads (Psilocarphus Brevissimus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail

*Non-native Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T24S.R3E.S33;T25S.R3E.S4 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Pseudotsuga menziesii Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ribes sanguineum Athyrium filix-femina Tsuga mertensiana Ribes viscosissimum Cystopteridaceae Taxaceae Rhamnaceae Cystopteris fragilis Taxus brevifolia Ceanothus velutinus Dennstaedtiaceae TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Rosaceae Pteridium aquilinum Adoxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dryopteridaceae Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea Holodiscus discolor Polystichum imbricans (Sambucus mexicana, S. cerulea) Prunus emarginata (Polystichum munitum var. imbricans) Sambucus racemosa Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Berberidaceae Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Berberis aquifolium (Mahonia aquifolium) Rubus leucodermis Equisetaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus nivalis Equisetum arvense (Mahonia nervosa) Rubus parviflorus Ophioglossaceae Betulaceae Botrychium simplex Rubus ursinus Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata Sceptridium multifidum (Alnus sinuata) Sorbus scopulina (Botrychium multifidum) Caprifoliaceae Spiraea douglasii Polypodiaceae Lonicera ciliosa Salicaceae Polypodium hesperium Lonicera conjugialis Populus tremuloides Pteridaceae Symphoricarpos albus Salix geyeriana Aspidotis densa Symphoricarpos mollis Salix scouleriana Cheilanthes gracillima (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Salix sitchensis Cryptogramma acrostichoides Celastraceae Salix sp. (Cryptogramma crispa) Paxistima myrsinites Sapindaceae Selaginellaceae (Pachystima myrsinites) -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Myosurus Australis

Myosurus australis FAMILY : RANUNCULACEAE BOTANICAL NAME : Myosurus australis F.Muell., Trans. Philos. Soc. Victoria 1: 6 (1854) COMMON NAME : Southern mousetail COMMONWEALTH STATUS (EPBC Act): Not Listed TASMANIAN STATUS (TSP Act): endangered Illustration by Richard Hale Description Myosurus australis is a short-lived annual herb with a rosette of rather fleshy narrow- linear leaves. The leaves are up to 10 cm long and have entire margins, and usually wither before fruit develops. Several simple flower stems arise from the base of the plant, each bearing a single flower; the stems are 1 to 3 cm long at flowering, elongating to up to 10 cm in fruit. The flowers are very small and greenish-yellow in colour; there are 5 sepals, each 3 to 5 mm long and with a basal spur, 0 to 5 minute petals and 5 to 10 stamens. The fruit consists of 100 to 300 small fruitlets (achenes) arranged along the top section of the flower stem in a dense slender spike up to 4 cm long. The achenes are dry, leathery and slightly flattened, with a short, erect beak (description from Curtis & Morris 1975, Walsh & Entwisle 1996). Flowering material has been collected in Tasmania in mid November; the species’ flowering period in Victoria is cited as September to November (Walsh & Entwisle 1996). [Myosurus australis was known previously as Myosurus minimus L. sensu Curtis & Morris (1975).] Distribution and Habitat Myosurus australis is endemic to Australia, occurring in all mainland States (Eichler et al. 2007). In Tasmania the species has been recorded at just two sites c. 55 km apart, one in the Southern Midlands and one in the Central Plateau, the altitude at the respective sites being 400 m and 925 m above sea level. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Little Mousetail)

Eighteen occurrences of Legenere limosa are (or were) on nature preserves or publicly-owned lands. Five occurrences are known currently from the Jepson Prairie Preserve in Solano County, two from the nearby Calhoun Cut Ecological Reserve, and two from the Dales Lake Ecological Reserve. Legenere limosa was known from Boggs Lake before the preserve was established, but it has not been rediscovered in that area for over 40 years (Holland 1984). Legenere limosa occurs in abundance in several vernal pools on the Valensin Ranch Property in Sacramento County owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy (J. Marty, unpub.data). A population of L. limosa was also discovered in a restored pool on Beale Air Force Base in Yuba County, California (J. Marty, unpub. data.). Two occurrences, at Hog Lake and on the Stillwater Plains, are on property administered by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. Sacramento County owns land supporting three occurrences of L. limosa; one is at a wastewater treatment plant, and the other two are in county parks. Finally, one occurrence is on land owned by the Sacramento Municipal Utility District (California Natural Diversity Data Base 2001). However, mere occurrence on public land is not a guarantee of protection. Only the preserves and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management occurrences are managed to promote the continued existence of L. limosa and other rare species. As of 1991, one Sacramento County developer had plans to preserve several pools containing L. limosa when he developed the property (California Natural Diversity Data Base 2001). 8. MYOSURUS MINIMUS SSP. APUS (LITTLE MOUSETAIL) a. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

Chapter Vii Table of Contents

CHAPTER VII TABLE OF CONTENTS VII. APPENDICES AND REFERENCES CITED........................................................................1 Appendix 1: Description of Vegetation Databases......................................................................1 Appendix 2: Suggested Stocking Levels......................................................................................8 Appendix 3: Known Plants of the Desolation Watershed.........................................................15 Literature Cited............................................................................................................................25 CHAPTER VII - APPENDICES & REFERENCES - DESOLATION ECOSYSTEM ANALYSIS i VII. APPENDICES AND REFERENCES CITED Appendix 1: Description of Vegetation Databases Vegetation data for the Desolation ecosystem analysis was stored in three different databases. This document serves as a data dictionary for the existing vegetation, historical vegetation, and potential natural vegetation databases, as described below: • Interpretation of aerial photography acquired in 1995, 1996, and 1997 was used to characterize existing (current) conditions. The 1996 and 1997 photography was obtained after cessation of the Bull and Summit wildfires in order to characterize post-fire conditions. The database name is: 97veg. • Interpretation of late-1930s and early-1940s photography was used to characterize historical conditions. The database name is: 39veg. • The potential natural vegetation was determined for each polygon in the analysis -

Alberta Wetland Classification System – June 1, 2015

Alberta Wetland Classification System June 1, 2015 ISBN 978-1-4601-2257-0 (Print) ISBN: 978-1-4601-2258-7 (PDF) Title: Alberta Wetland Classification System Guide Number: ESRD, Water Conservation, 2015, No. 3 Program Name: Water Policy Branch Effective Date: June 1, 2015 This document was updated on: April 13, 2015 Citation: Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (ESRD). 2015. Alberta Wetland Classification System. Water Policy Branch, Policy and Planning Division, Edmonton, AB. Any comments, questions, or suggestions regarding the content of this document may be directed to: Water Policy Branch Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development 7th Floor, Oxbridge Place 9820 – 106th Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2J6 Phone: 780-644-4959 Email: [email protected] Additional copies of this document may be obtained by contacting: Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Information Centre Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 108 Street Edmonton Alberta Canada T5K 2M4 Call Toll Free Alberta: 310-ESRD (3773) Toll Free: 1-877-944-0313 Fax: 780-427-4407 Email: [email protected] Website: http://esrd.alberta.ca Alberta Wetland Classification System Contributors: Matthew Wilson Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Thorsten Hebben Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Danielle Cobbaert Alberta Energy Regulator Linda Halsey Stantec Linda Kershaw Arctic and Alpine Environmental Consulting Nick Decarlo Stantec Environment and Sustainable Resource Development would also -

Appendix C. Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grasslands Regional Park (2009-2010)

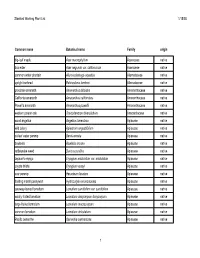

Appendix C. Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grasslands Regional Park (2009-2010) Plant Species Observed at the Yolo Grassland Regional Park (2009-2010) Wetland Growth Indicator Scientific Name Common Name Habitat Occurrence Habit Status Family Achyrachaena mollis Blow wives AG, VP, VS AH FAC* Asteraceae Aegilops cylinricia* Jointed goatgrass AG AG NL Poaceae Aegilops triuncialis* Barbed goat grass AG AG NL Poaceae Aesculus californica California buckeye D T NL Hippocastanaceae Aira caryophyllea * [Aspris c.] Silver hairgrass AG AG NL Poaceae Alchemilla arvensis Lady's mantle AG AH NL Rosaceae Alopecurus saccatus Pacific foxtail VP, SW AG OBL Poaceae Amaranthus albus * Pigweed amaranth AG, D AH FACU Amaranthaceae Amsinckia menziesii var. intermedia [A. i.] Rancher's fire AG AH NL Boraginaceae Amsinckia menziesii var. menziesii Common fiddleneck AG AH NL Boraginaceae Amsinckia sp. Fiddleneck AG, D AH NL Boraginaceae Anagallis arvensis * Scarlet pimpernel SW, D, SS AH FAC Primulaceae Anthemis cotula * Mayweed AG AH FACU Asteraceae Anthoxanthum odoratum ssp. odoratum * Sweet vernal grass AG PG FACU Poaceae Aphanes occidentalis [Alchemilla occidentalis] Dew-cup AG, F AH NL Rosaceae Asclepias fascicularis Narrow-leaved milkweed AG PH FAC Ascepiadaceae Atriplex sp. Saltbush VP, SW AH ? Chenopodiaceae Avena barbata * Slender wild oat AG AG NL Poaceae Avena fatua * [A. f. var. glabrata, A. f. var. vilis] Wild oat AG AG NL Poaceae Brassica nigra * Black mustard AG, D AH NL Brassicaceae Brassica rapa field mustard AG, D AH NL Brassicaceae Briza minor * Little quakinggrass AG, SW, SS, VP AG FACW Poaceae Brodiaea californica California brodiaea AG PH NL Amaryllidaceae Brodiaea coronaria ssp. coronaria [B. -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Bryce

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 ON THE COVER Matted prickly-phlox (Leptodactylon caespitosum), Bryce Canyon National Park, Utah. Photograph by Walter Fertig. Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora Bryce Canyon National Park Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR–2009/153 Author Walter Fertig Moenave Botanical Consulting 1117 W. Grand Canyon Dr. Kanab, UT 84741 Sarah Topp Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 Editing and Design Alice Wondrak Biel Northern Colorado Plateau Network P.O. Box 848 Moab, UT 84532 January 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Fort Collins, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientifi c community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifi cally credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. The Natural Resource Technical Report series is used to disseminate the peer-reviewed results of scientifi c studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service’s mission. The reports provide contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. -

Myosurus Minimus Subsp. Novae-Zelandiae (W.R.B.Oliv.) Garn.-Jones

Myosurus minimus subsp. novae- zelandiae COMMON NAME New Zealand mousetail SYNONYMS Myosurus novae-zelandiae W.R.B.Oliv., M. minimus L. subsp. minimus FAMILY Ranunculaceae AUTHORITY Myosurus minimus subsp. novae-zelandiae (W.R.B.Oliv.) Garn.-Jones FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes Blackstone Hill. Photographer: John Barkla ENDEMIC GENUS No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Herbs - Dicotyledons other than Composites NVS CODE MYOMSN CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 16 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2018 | Threatened – Nationally Vulnerable PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2012 | Threatened – Nationally Endangered | Qualifiers: DP, EF, RR, Sp Photographer: Neil Simpson 2009 | Threatened – Nationally Critical | Qualifiers: EF, Sp 2004 | Threatened – Nationally Endangered DISTRIBUTION Endemic to New Zealand, North and South Islands. Formerly reported from the Hawkes Bay to Cape Palliser and Island Bay near Wellington (places where it is now believed extinct). In the South Island it is known only from the eastern side, from Marlborough south to Lake Manapouri. HABITAT Lowland to upland. Damp and slightly salty depressions in pastures and short tussock grassland, on the margins of tarn and kettle holes, and in damp dune hollows, gravel flats and alluvium. FEATURES Spring to summer-green annual, forming tufts 10–80mm tall. Leaves 5–20, 10–35 × 1–2.5mm, basal, fleshy to succulent, exstipulate, linear to linear-spathulate, obtuse, margins entire, bright to dark green, yellow-green, red- green or red. Inflorescences scapigerous, scapes 1–8, 1-flowered, 10–80mm tall (including receptacle), erect to spreading, glabrous, fleshy, filiform, bright to dark green, yellow-green, red-green or red. Flowers greenish–yellow, apetalous. Sepals 5, minute, 0.5–0.8mm long, 3-nerved, ovate to oblanceolate, green to greenish-yellow or green- red, Stamens 5, filaments 0.3–0.5mm long, greenish-white.