The Search for Self and Space by Indian Dalit Joseph Macwan and African American Richard Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E-Newsletters, Publicity Materials Etc

DELHI SAHITYA AKADEMI TRANSLATION PRIZE PRESENTATION September 4-6, 2015, Dibrugarh ahitya Akademi organized its Translation Prize, 2014 at the Dibrugarh University premises on September 4-6, 2015. Prizes were presented on 4th, Translators’ Meet was held on 5th and Abhivyakti was held on S5th and 6th. Winners of Translation Prize with Ms. Pratibha Ray, Chief Guest, President and Secretary of Sahitya Akademi On 4th September, the first day of the event started at 5 pm at the Rang Ghar auditorium in Dibrugarh University. The Translation Prize, 2014 was held on the first day itself, where twenty four writers were awarded the Translation Prizes in the respective languages they have translated the literature into. Dr Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari, President, Sahitya Akademi, Eminent Odia writer Pratibha Ray was the chief guest, Guest of Honor Dr. Alak Kr Buragohain, Vice Chancellor, Dibrugarh University and Dr K. Sreenivasarao were present to grace the occasion. After the dignitaries addressed the gathering, the translation prizes were presented to the respective winners. The twenty four awardees were felicitated by a plaque, gamocha (a piece of cloth of utmost respect in the Assamese culture) and a prize of Rs.50, 000. The names of the twenty four winners of the translation prizes are • Bipul Deori won the Translation Prize in Assamese. • Benoy Kumar Mahanta won the Translation Prize in Bengali. • Surath Narzary won the Translation Prize in Bodo. • Yashpal ‘Nirmal’ won the Translation Prize in Dogri • Padmini Rajappa won the Translation Prize in English SAHITYA AKADEMI NEW S LETTER 1 DELHI • (Late) Nagindas Jivanlal Shah won the Translation Prize in Gujarati. -

UNPAID DIVIDEND for the YEAR 2011-2012 Sr

VAKRANGEE LIMITED UNPAID DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2011-2012 Sr. No. Folio No./DPCLID Name of the Shareholder Shareholder Address Dividend Proposed Amount date of transfer to IEPF 1 '0009388 NALINI MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 2 '0009389 ASHWIN MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 3 '0009390 RUPAL MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 4 '0009391 BELA MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 5 '0009392 REKHA MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 6 '0009393 INDIRA MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 7 '0009394 BHARAT MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 8 '0009395 KIRIT MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 9 '0009405 BHARTI GORECHIA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 10 '0009411 DHIRENDRA MEHTA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 11 '0009412 RAKESH KANAKIA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 12 '0009414 RUPAL GORADIA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 13 '0009413 KETAN GORADIA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 14 '0009417 VARSHA CHAWDA 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 400 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY 400026 15 '0009420 GUNVANTRAI DOSHI 153/B HEERA PANNA BHULABHAI DESAI 800 28.09.2019 ROAD BOMBAY -

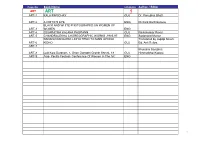

Book Name Language Author / Editor ART ART-1 KALA PARICHAY GUJ

Code No: Book Name Language Author / Editor ART ART 1 ART-1 KALA PARICHAY GUJ Dr. Panubhai Bhatt ART-2 A CRITIC'S EYE ENG Richard Bartholomew BLACK AND WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS ON WOMEN OF ART-3 WOMEN ENG ART-4 GUJARATMA KALANA PAGRANN GUJ Ravishankar Raval ART-5 CHANDRALEKHA CHOREOGRAPHIC WORKS -1985-97 ENG Sadanand Menon DADANO DANGORO LIDHO TENO TO MAIN GHODO Translated by Jagdip Smart, ART-6 KIDHO GUJ Ed. Anil Reliya, ART-7 Mrunalini Sarabhai. ART-8 Lalit Kala Darshan- 1, Gnan Gangotri Granth Shreni- 18 GUJ Himmatbhai Kapasi, ART-9 Asia- Pecific Festival- Conference Of Women In The Art ENG 1 Code No: Book Name Language Author / Editor END AUT AUTO BIOGRAPHY / BIOGRAPHY 2 BHAKT SHRI NARSINH MEHTANA JIVAN PRASANGO NI AUT-1 ZANKHI GUJ AUT-2 YASHWANTH SMRITI GUJ Gulab Bheda AUT-3 PARICHAY PUSTIKA -1996 - INDULAL YAGNIK GUJ Digant Oza, Ed. Suresh Dalal Sanjay Bhave, Ed. Jitendra AUT-4 PARICHAY PUSTIKA -1093 - P.L. DESHPANDE GUJ Desai AUT-5 MADAM KAMA (JIVAN CHARITRA) GUJ Bulu Roychaoudhary FLAVIA EGNIS, Ed. And PRAWAAZ- Tuti Bikhari Zindagi Ko Savarne Ki Meri Kahani, Translated by Nasiruddin AUT-6 Ham Sab Ki Kahani HIN Haidar Khan FLAVIA EGNIS, Ed. And PRAWAAZ- Tuti Bikhari Zindagi Ko Savarne Ki Meri Kahani, Translated by Nasiruddin AUT-7 Ham Sab Ki Kahani HIN Haidar Khan AUT-8 NIJI AKASH GUJ Ranjana Harish AUT-9 KYON TERA RAHEGUZAR YAAD AAYA GUJ Varsha Adalaj AUT-10 ATHMAKATHA: SWAROOP ANE VIKAS GUJ Dr. Rasila Chandrakant Kadia AUT-11 GULAM GIRI GUJ Mahatma Jyotirav Phoole SAMAJIK KSHETRAT PARIVARTANWADI VICHAR AUT-12 FULVINACHYA - MADHYAMRANGI MAR Sujata Babar Transkated by Swami Krishna AUT-13 NAVIN YUGNA UDGATA YUGPURUSH OSHO GUJ Teerth AUT-14 KABIR HIN HAJARI PRASAD DVIVEDI AUT-15 VAITALIK GUJ Dr. -

Annual Report 2018–2019

Annual Report 2018–2019 Sahitya Akademi (National Academy of Letters) President : Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar Vice-President : Sri Madhav Kaushik Secretary : Dr K. Sreenivasarao ............................................CONTENTS Sahitya Akademi 5 Projects and Schemes 8 Highlights of 2018–2019 12 Awards 13 – Sahitya Akademi Award 2018 15 – Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2018 19 – Yuva Puraskar 2018 23 – Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2018 27 Programmes 31 – Sahitya Akademi Awards 2018 Presentation Ceremony 32 – Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2017 Presentation Ceremony 55 – Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar 2018 Presentation Ceremony 58 – Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2018 Presentation Ceremony 63 – Seminars, Symposia, Writers’ Meets, etc. 68 List of Programmes organized by Sahitya Akademi in 2018–2019 152 Governing Body, Regional Board Meetings and Language Advisory Boards held in 2018–2019 180 Book Exhibitions / Book Fairs 183 Books Published 191 Annual Accounts 231 SAHITYA AKADEMI (National Academy of Letters) Sahitya Akademi, India’s premier Institution levels, more than 100 Symposia and a large of Letters, preserves and promotes literature number of birth centenary seminars and in 24 languages of India recognized by it. It symposia, in addition to more than 400 literary organizes programmes, confers Awards and gatherings, workshops and lectures. Meet the Fellowships on writers in Indian languages, Author (where a distinguished writer talks about and publishes books throughout the year and his / her works and life), Samvatsar Lectures in 24 recognized -

Annual Report 2017-18

Annual Report 2017-18 Sahitya Akademi (National Academy of Letters) President : Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar Vice-President : Sri Madhav Kaushik Secretary : Dr K. Sreenivasarao CONTENTS New President and Vice President of Sahitya Akademi 4 Sahitya Akademi 5 Highlights of 2017-2018 9 Awards 10 - Sahitya Akademi Award 2017 11 - Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2017 15 - Yuva Puraskar 2017 19 - Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2017 23 Programmes 27 - Presentation of Sahitya Akademi Awards 2017 28 - Presentation of Sahitya Akademi Prize For Translation 2016 39 - Presentation of Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar 2017 42 - Presentation of Sahitya Akademi Bal Sahitya Puraskar 2017 44 - Seminars, Symposia And Conferences 48 List of Programmes organized by Sahitya Akademi in 2017-2018 106 Governing Body, Language Advisory Boards and Regional Board Meetings Held in 2017-2018 129 Projects and Schemes 130 Book Exhibitions / Book Fairs 134 Books Published 142 Annual Accounts 177 New President and Vice President of Sahitya Akademi The General Council of Sahitya Akademi, in its 188th meeting, elected two distinguished litterateurs, Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar and Sri Madhav Kaushik, as President and Vice President of Sahitya Akademi, respectively. Their tenure is for the period of five years between 2018 and 2022. Dr Chandrashekhar Kambar is a prominent of India, Jnanpith Award, Sahitya Akademi poet, playwright, folklorist, film director in Award, Sangeet Natak Akademi Award, Sangeet Kannada language and the founder Vice- Natak Akademi Fellowship, Kabir Samman, Chancellor of Kannada University in Hampi. Kalidas Samman, Nadoja Award, Pampa Award He is well-known for his effective adaptation and Karnataka Sahitya Akademi Award. of the North Karnataka dialect of the Kannada language in his plays, and poems.