Final:English 18 Factsheet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bathinda 12000 Jagsir Singh S/O Dev S/O Darshan Singh Singh 23 Kulwant Talwandi Talwandi 12000 Jagsir Singh Singh S/O Sabo Sabo S/O Darshan Krishan Singh Singh

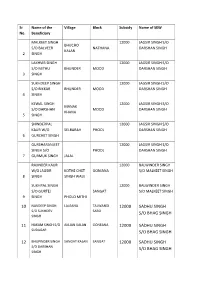

Sr Name of the Village Block Subsidy Name of SEW No. Beneficiary MALKEET SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O BHUCHO S/O BALVEER NATHANA DARSHAN SINGH KALAN 2 SINGH LAKHVIR SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O S/O MITHU BHUNDER MOOD DARSHAN SINGH 3 SINGH SUKHDEEP SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O S/O BIKKAR BHUNDER MOOD DARSHAN SINGH 4 SINGH KEWAL SINGH 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O MANAK S/O DARSHAN MOOD DARSHAN SINGH KHANA 5 SINGH SHINDERPAL 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O KAUR W/O SELBARAH PHOOL DARSHAN SINGH 6 GURCHET SINGH GURSHARANJEET 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O SINGH S/O PHOOL DARSHAN SINGH 7 GURMUK SINGH JALAL RAJINDER KAUR 12000 BALWINDER SINGH W/O JAGSIR KOTHE CHET GONIANA S/O MALKEET SINGH 8 SINGH SINGH WALE SUKHPAL SINGH 12000 BALWINDER SINGH S/O GURTEJ SANGAT S/O MALKEET SINGH 9 SINGH PHOLO MITHI 10 NAVDEEP SINGH LALEANA TALWANDI 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O SUKHDEV SABO S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 11 HAKAM SINGH S/O AKLIAN KALAN GONEANA 12000 SADHU SINGH SUDAGAR S/O BHAG SINGH 12 BHUPINDER SINGH SANGAT KALAN SANGAT 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O DARSHAN S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 13 BHUPINDER SINGH BHAGTA BHAGTA 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O NIRBHAI S/O BHAG SINGH SINGH 14 GURNAM SINGH JANDA WALA GONEANA 12000 SADHU SINGH S/O DALIP SINGH S/O BHAG SINGH 15 SURJIT SINGH S/O MALKANA TALWANDI 12000 AMARJEET SINGH GANDA SINGH SABO S/O GURDIAL SINGH 16 TARSEM SINGH MALKANA TALWANDI 12000 AMARJEET SINGH S/O GURDARSHAN SABO S/O GURDIAL SINGH SINGH 17 HARMESH SINGH GEHLEWALA TALWANDI 12000 HARBANS SINGH S/O GURBACHAN SABO S/O HARDIAL SINGH SINGH 18 JAGJEET SINGH GUMTI PHOOL 12000 JAGSIR SINGH S/O BASANT KALAN -

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT and INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session

Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q1. A. B. C. D. Q2. A. B. C. D. Q3. A. B. C. D. Q4. A. B. C. D. Q5. A. B. C. D. February 23, 2020 Page 1 of 26 Adv. No. 12/2019, Cat No. 65, Junior Programer, SKIL DEVELOPMENT AND INDUSTRIAL TRAINING DEPARTMENT, HARYANA Evening Session Q6. __________ is the synonym of "JOIN." A. Release B. Attach C. Disconnect D. Detach Q7. __________ is the antonym of "SYMPATHETIC." A. Insensitive B. Thoughtful C. Caring D. Compassionate Q8. Identify the meaning of the idiom "Miss the boat." A. Let too much time go by to complete a task. B. Long for something that you don't have. C. Miss out on an opportunity. D. Not know the difference between right and wrong. Q9. The sentence has an incorrect phrase, which is in bold and underlined. Select the option that is the correct phrase to be replaced so that the statement is grammatically correct. "I train to be a pilot because my dream is to join the Air Force." A. am training B. would train C. are training D. will have trained Q10. Complete the sentence by choosing the correct form of the verb given in brackets. I was very grateful that he _____ (repair) my computer so promptly. A. repairs B. will be repairing C. will repair D. repaired Q11. Which was the capital of Ashoka's empire? A. Ujjain B. Taxila C. Indraprastha D. Pataliputra February 23, 2020 Page 2 of 26 Adv. -

E3 Fh Fhft Meha (A.Fh) Afszt

E3 fH fHfT mEHa (A.fH) afszT HHU Ho HHÍ HJH/HHH} HA afos dse -SLA elkno28 fr 31/05/2021 fe-SLA zaföa Hstt euda fe Hau SCERT 6B7 SCERT/SCI/2021 22/2021170660f+t 28/05/2021 MaHG MA. E. SH n5 TEa FT OT fst 01/ ga/2021 a 02/H6/2021 aa argt FHT 9:30AM 3 12:30PM JEaTI H H st HUS fos f5tT 05 Ha% TU HHE JT SLA (Hfos) 1. fa tua 3 ad SLA whatsapp group fea HTH TET uatat aarfe Tatst asreI 3. 200M APP msz a et HrI 6. Z0OM APP äfars aaè HÀ MT 5H musz aa fwr aT 7. Z0OM APP 3 2f$ar föa 30 ffz ufr sn fts HaT| SLA as on Sr no. Edu Block Name 26.05.2021 School Name/Office 1 BATHINDA GSSS JODHPUR ROMANA Name Mobile No. | kanwaljeet kaur BATHINDA DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA 9417238341| Boys AMANDEEP KAUR 9915116537 BATHINDA DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA Boys BALVIR KAUR 9217252848 4 BATHINDA |DES RAJ MEM GSSS BATHINDA Boys HARINDER SINGH BATHINDA GSSS MULTANIA 9815091720 BATHINDA Karamjit Singh GSSS GULABGARH GURBINDER SINGH 9417439547 BATHINDA GSSS PARASRAM NAGAR BTD 7696612656 8 BATHINDA JASWINDER SINGH 9478881225 GSSS PARASRAM NAGAR BTD |Karmjit kaur BATHINDA GSSS SIVIAN 9463835758| Parmjit Kaur 10 BATHINDDA GSSS BALLUANA 9478772972| 11 BATHINDA GSSS Yogesh Kumar 9878911334| PARASRAM NAGAR BTD RUPINDER PAL SINGH BATHINDA GSSS KOT SHAMIR 9417109929| 13 BATHINDA AMREEK SINGH 9464151511| GSSS BEHMAN DIWANA KAMAL KANT SHAHEED MAJOR RAVI INDER 9417036855 14 BATHINDA SINGH SANDHU GSSS MALL ROAD GIRLS BATHINDA Patwinder Singh 9464100036 15 BHAGTA BHAI KA GSSS BHAGTA SUKHCHAIN SINGH 16 BHAGTA BHAI KA GSSS DHAPPALI 9501335682| BHAGTA Sunil Kumar 17 BHAI KA GSSS MALUKA -

Hydrogeological Characterization and Assessment of Groundwater Quality in Shallow Aquifers in Vicinity of Najafgarh Drain of NCT Delhi

Hydrogeological characterization and assessment of groundwater quality in shallow aquifers in vicinity of Najafgarh drain of NCT Delhi Shashank Shekhar and Aditya Sarkar Department of Geology, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 007, India. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] Najafgarh drain is the biggest drain in Delhi and contributes about 60% of the total wastewater that gets discharged from Delhi into river Yamuna. The drain traverses a length of 51 km before joining river Yamuna, and is unlined for about 31 km along its initial stretch. In recent times, efforts have been made for limited withdrawal of groundwater from shallow aquifers in close vicinity of Najafgarh drain coupled with artificial recharge of groundwater. In this perspective, assessment of groundwater quality in shallow aquifers in vicinity of the Najafgarh drain of Delhi and hydrogeological characterization of adjacent areas were done. The groundwater quality was examined in perspective of Indian as well as World Health Organization’s drinking water standards. The spatial variation in groundwater quality was studied. The linkages between trace element occurrence and hydrochemical facies variation were also established. The shallow groundwater along Najafgarh drain is contaminated in stretches and the area is not suitable for large-scale groundwater development for drinking water purposes. 1. Introduction of this wastewater on the groundwater system is even more profound. There is considerable contam- The National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi ination of groundwater by industrial and domestic (figure 1) is one of the fast growing metropoli- effluents mostly carried through various drains tan cities in the world. It faces a massive problem (Singh 1999). -

On the Brink: Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana By

Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana August 2010 For copies and further information, please contact: PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar, Phase I, Delhi – 110 091, India Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development PEACE Institute Charitable Trust P : 91-11-22719005; E : [email protected]; W: www.peaceinst.org Published by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 178-F, Pocket – 4, Mayur Vihar – I, Delhi – 110 091, INDIA Telefax: 91-11-22719005 Email: [email protected] Web: www.peaceinst.org First Edition, August 2010 © PEACE Institute Charitable Trust Funded by Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) under a Sir Dorabji Tata Trust supported Water Governance Project 14-A, Vishnu Digambar Marg, New Delhi – 110 002, INDIA Phone: 91-11-23236440 Email: [email protected] Web: www.watergovernanceindia.org Designed & Printed by: Kriti Communications Disclaimer PEACE Institute Charitable Trust and Society for Promotion of Wastelands Development (SPWD) cannot be held responsible for errors or consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. All rights reserved. Information contained in this report may be used freely with due acknowledgement. When I am, U r fine. When I am not, U panic ! When I get frail and sick, U care not ? (I – water) – Manoj Misra This publication is a joint effort of: Amita Bhaduri, Bhim, Hardeep Singh, Manoj Misra, Pushp Jain, Prem Prakash Bhardwaj & All participants at the workshop on ‘Water Governance in Yamuna Basin’ held at Panipat (Haryana) on 26 July 2010 On the Brink... Water Governance in the Yamuna River Basin in Haryana i Acknowledgement The roots of this study lie in our research and advocacy work for the river Yamuna under a civil society campaign called ‘Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan’ which has been an ongoing process for the last three and a half years. -

Tehsil Bathinda, District Bathinda (151001) (Rate List for Online) Rs.) 2020-21 Sr

Agriculture (Rate in Rs.) Non Agriculture (Rate in Tehsil Bathinda, District Bathinda (151001) (Rate List For Online) Rs.) 2020-21 Sr. No. Develope Village Name Location Type Location Name (Local language) Survey Number/ Door Number Code ngdrs Agriculture Agricultur Agriculture Residenti Commerc Unit d Land (Local Language) (Local Language) Numbe LandNehri/ e Land(Gair al ial Type r Chahi LandBrani Mumkin (Rural/ Abadi) 1 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ From Mall Road, Hanuman Chowk to Stationing (up to a depth of 120 feet) ਭਾਰ ਯਡ, ਿਨਿੰ ਭਾਨ ਚਕ ਤ ਸਟੇਸਨ ਤੱ ਕ 2036,2030,2025 1 1 60000 ਵਯਗ ਗਜ (120 ਪੱ ਟ ਦੀ ਡਿੰ ਘਾਈ ਤੱ ਕ) 2 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ Textile Market ਕੱ ੜਾ ਭਾਯਕੀਟ 2030 1 2 30000 ਵਯਗ ਗਜ 3 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਠਯਿਾਇਸੀ / From Main Road Rajendra College to Naw Bus Stand, up to a depth of 90 feet ਭੇਨ ਯਡ ਯਾਠਜਿੰ ਦਯ ਕਾਰਜ ਤ ਨਵਾ ਫੱ ਸ ਸਟੈਡ 3749,3757, 3747 1 4/ 150 10000 25000 ਵਯਗ ਗਜ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ ਤੱ ਕ 90 ਪੱ ਟ ਦੀ ਡਿੰ ਘਾਈ ਤੱ ਕ 4 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ From a main road new bus stand to Pukhraj Cinema 90-foot-depth ਭੇਨ ਯਡ ਨਵਾ ਫੱ ਸ ਸਟੈਡ ਤ ਖਯਾਜ ਠਸਨੇ ਭਾ 2487,2479,2467,2469,2486, 2470, 2447, 2036, 2037, 2038, 1 5 30000 ਵਯਗ ਗਜ ਤੱ ਕ 90 ਪੱ ਟ ਦੀ ਡਿੰ ਘਾਈ ਤੱ ਕ 5 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ From Main Road Pukhraj cinema to Tin Koni upto a depth of 90 feet up ਭੇਨ ਯਡ ਖਯਾਜ ਠਸਨੇ ਭਾ ਤ ਠਤਿੰ ਨ ਕਣੀ ਤੱ ਕ 2036,2039,2040, 2014,2015,2037, 2038, 2045 1 6 30000 ਵਯਗ ਗਜ 90 ਪੱ ਟ ਦੀ ਡਿੰ ਘਾਈ ਤੱ ਕ 6 Urban ਫਠ ਿੰ ਡਾ ੱ ਤੀ ਭਠਿਣਾ ਕਭਯਸੀਅਰ GT Road near Gupta Iron Store street commercial (up to a depth of 60 feet) ਜੀ.ਟੀ. -

Chapter 2 Forgotten History Lessons, Delhi's Missed Date with Water

Jalyatra – Exploring India’s Traditional Water Management Systems Chapter 2 Forgotten history lessons, Delhi’s missed date with water India’s capital is one of the oldest cities of India, indeed of the world, if you believe mythology. It began as Indraprastha probably around 5,000 BC, grew through seven other cities into New Delhi. Among the metros, Delhi is certainly the only one old enough to have a tradition of water conservation and management that developed indigenously and wasn’t imposed by the British. Delhi lies at the tail-end of the Aravali hills, where they merge with the Indo-Gangetic Plains. The Aravalis taper down from the southern to the northern end of Delhi, forming one watershed. Along the southern side, they run east-west forming another watershed. All the drains and seasonal streams flow north and east in Delhi, some making it to the river Yamuna, others terminating in depressions to form lakes and ponds. These artificial ponds helped recharge wells, that were the only source of water in the rocky Aravali region, and the baolis that also tap into groundwater flows, in the rest of the city. The rocky Aravalis were ideal for bunding and making more such depressions to store water that was used either by people or recharged the aquifers. In south Delhi and a little beyond, there are many artificial lakes and ponds created centuries ago for just this purpose. The western part of Delhi falls in the Najafgarh drain’s watershed, which was originally a river that rose in the Sirmaur hills in Haryana. -

Blue Riverriver

Reviving River Yamuna An Actionable Blue Print for a BLUEBLUE RIVERRIVER Edited by PEACE Institute Charitable Trust H.S. Panwar 2009 Reviving River Yamuna An Actionable Blue Print for a BLUE RIVER Edited by H.S. Panwar PEACE Institute Charitable Trust 2009 contents ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................................................... v PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 Fact File of Yamuna ................................................................................................. 9 A report by CHAPTER 2 Diversion and over Abstraction of Water from the River .............................. 15 PEACE Institute Charitable Trust CHAPTER 3 Unbridled Pollution ................................................................................................ 25 CHAPTER 4 Rampant Encroachment in Flood Plains ............................................................ 29 CHAPTER 5 There is Hope for Yamuna – An Actionable Blue Print for Revival ............ 33 This report is one of the outputs from the Ford Foundation sponsored project titled CHAPTER 6 Yamuna Jiye Abhiyaan - An Example of Civil Society Action .......................... 39 Mainstreaming the river as a popular civil action ‘cause’ through “motivating actions for the revival of the people – river close links as a precursor to citizen’s mandated actions for the revival -

BATHINDA Punjab School Education Board

22/03/19 Punjab School Education Board Page 1 List of Observers appointed for Exam, March 2019 District BATHINDA Matric Exam Date 25/03/2019 Centre Code Centre Name Sr. No. Epunjab Id Name & Designation & School Name 15020 SANGAT MANDI : SIPAHI JAILA SINGH VIR CHAKRA GOVT SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SANGAT MANDI 1. 620144279 VISHALI / VED PRAKASH, LECTURER (ECONOMICS) [F] 9463403345 GSSS MULTANIA {0020503} 15030 SIVIAN : GOVT.SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SIVIAN 1. 693964206 EKANKI KAPOOR / O P KAPOOR, LECTURER (ENGLISH) [F] 9417319715 GSSS POOHLA {0019855} 15080 HARRAIPUR : SHAHID SIPAHI HARBANS SINGH GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL HARRAIPUR 1. 313810307 RAJESH KUMAR / VED PARKASH, LECTURER (PHYSICAL EDUCATION) [M] 9465628169 GSSS SANJAY NAGAR BATHINDA (RMSA) {0018135} 15090 KARAR VALA-1 : GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL KARARWALA 1. 785234348 NARESH KUMAR / BHAGWAN SINGH, LECTURER (MATHEMATICS) [M] 9417473805 GSSS LEHRI {0020433} 15100 KOT SHAMEER : GOVT. SECONDARY SCHOOL KOT SHAMIR 1. 219603197 BALJEET KAUR / BAL MUKAND SHARMA, LECTURER (ENGLISH) [F] 9876385566 GSSS CHAK FATEH SINGH WALA {0024017} 15120 KALYAN SUKHA : GOVT. SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL KALYAN SUKHA 1. 576627833 KRISHAN KUMAR GUPTA / SH. OM PARKASH GUPTA, PRINCIPAL (ALL SUBJECTS) [M] 9501008960 GSSS BHOKHRA {0019174} 15130 KOTHA GURU : GOVT. SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL (BOYS) KOTHA GURU 1. 624116870 JARNAIL SINGH / GURCHARAN SINGH, LECTURER (ECONOMICS) [M] 9463541864 GSSS JETHUKE {0020363} 15140 KOT FATTA : SHAHEED SIPAHI DARSHAN SINGH GOVT. SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL KOT FATTA 1. 848811775 TARANJIT / HARBHAJAN SINGH, LECTURER (ENGLISH) [F] 9646208513 GSSS SANGAT MANDI {0020605} 15150 KAMALU SWAITCH : GOVT. SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL KAMALU SWAITCH 1. 739606040 HARPREET KAUR / GANGA SINGH, MASTER CADRE (ENGLISH) [F] 9878055641 GSSS BANGI KALAN {0020096} 15170 KOTBHAG : GOVT. SENIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL KOT BHARA 1. -

Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management

In ternational Journal of Energy and Environmental Science 2020; 5(1): 14-29 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijees doi: 10.11648/j.ijees.20200501.13 ISSN: 2578-9538 (Print); ISSN: 2578-9546 (Online) Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management Natarajan Pachamuthu Muthaiyah Department of Centre for Climate Change, Periyar Maniammai University, Thanjavur, India Email address: To cite this article: Natarajan Pachamuthu Muthaiyah. Rejuvenating Yamuna River by Wastewater Treatment and Management. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Science. Vol. 5, No. 1, 2020, pp. 14-29. doi: 10.11648/j.ijees.20200501.13 Received : July 12, 2020; Accepted : November 13, 2020; Published : MM DD, 2020 Abstract: Yamuna is the most important tributary of Ganga River originating from the Yamunotri glacier of Himalaya, the ‘Asian Water Tower ’. Since Yamuna is fed by the above glacier, the Ganga River supplies water perennially. The catchment area of Yamuna River is 3, 45,848km 2 which is the largest among the other tributaries of Ganga. Surface water resource of the Yamuna River is 61.22km 3 and the net groundwater availability is 45.43km 3. Total sewage generation per annum from domestic and industrial sources in Yamuna River basin is about 9.63km 3. Due to the mixing of the above human influenced sewage, the waterways of this basin are stinking in many reaches and almost dead near Delhi. The pollution loads of the stinking and dead reaches of this river pollute the groundwater of the Yamuna River basin in many reaches. To treat and recycle the above sewage load about 1,320 sewage treatment plants are necessary. -

Case Study of Najafgarh Drain

Case study of Najafgarh Drain - A rich wetland ecosystemin Delhi turning into a highly polluted water body Dr.Nibedita Khuntia*, Esha Govil**, Vikas** and Cessna Sahu** *Assistant Professor, Department of Biology, ** B. Tech, Department of Computer Science– Maharaja Agrasen College, Universityof Delhi Abstract Over the past years due to rigorous agricultural practice, urbanization,rapid industrialization and daily household activities, water pollution has becomea major issue. These factors have played havoc on a water body in the national capital of India as well.The famous Najafgarh Drain in Delhi, once a rich wetland,has turned into one of the most polluted water body in the country. This paper discusses the ecological importance of the drain, the causes and effects of the subsequent decline in its quality. It also discusses the findings of two field visits undertaken to understand the local effects of water pollution of the drain on the lives of residents who live in proximity of the drain. Keywords: Najafgarh Drain, pollution loads, industrialization, urbanization, sewage disposal, environmental degradation Introduction: The famous Najafgarh drain (See Map in Figure 1) in the national capital of the country got its name from a town called Najafgarh in South West Delhi. It is now recognized as the “Ganda Nallah” by the residents of the city due to high levels of pollution. The situation is so bad, that in 2005, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) stamped it as a highly polluted drain and put it under “D” category with other 13 highly polluted wetlands(7). This wasn't always the state of the drain. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Bathinda, Part XIII a & B

CENSUS 1981 SERIES 17 VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT BATHINDA DISTRICT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK D. N. OHIR OF THE INDIAN ADMINisTRATIvE SERVICa DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB ----------------; 10 d '" y.. I 0 B i i© ~ 0 :c « :I:'" :I: l- I :!. :I: 1 S z VI "- Ir .t:. 0 III 0 i i I@ 11 Z If i i I l l I ~ 2 m 0 0 UJ 0 u.j ~ >' g: g: .. ~ -,'" > .. g U '" iii 2 « V1 0 ",' ..'" ..' (() 2 ~ <;;''" ~ .. - I 0 LL ~ ) w m '" .. 0 :> 2 0 i 0: <l <l ;: .. iii "- 9 '" ~ 0 I Z !? I- 0 l- 0 ~ <l Z UJ "- 0 I- 0: l- t- 0 ::I: :'\ z u Vl <II r oz ~ :::> :> "- 20 o!;i I <l I I 0: 0 <{ 0 0-' S I- "- I- I <l>' II) ii 0 0 3: ,.." VI ;:: t- Ir 0::> 0... 0 0 0 U j <!) ::> ",,,- t> 3i "- 0 ~ 0 ;t g g g ;: 0 0 S 0: iii ,_« 3: ~ "'t: uJ 0 0' ~' ~. ",''" w '" I-- I ~ "'I- ","- U> (D VI I ~ Will 0: <t III <!) wW l!! Z 0:: S! a 0:: 3: ::I: "'w j~ .... UI 0 >- '" zt!> UJ :;w z., OJ 'i: ::<: z'"- « -<t 0 (/) '"0 WVl I-- ~ :J ~:> 0 «> "! :; >- 0:: I-- z u~ ::> ::<:0 :I: 0:,\ Vl - Ir i'" z « 0 m '" « -' <t I l- til V> « ::> <t « >- '" >- '" w'o' w« u ZO <t 0 z .... «0 Wz , 0 w Q; <lw u-' 2: 0 0 ~~ I- 0::" I- '" :> • "« =0 =1-- Vl (/) ~o ~ 5 "- <{w "'u ~z if> ~~ 0 W ~ S "'"<to: 0 WUJ UJ "Vl _e ••• · m r z II' ~ a:m 0::>: "- 01-- a: :;« is I _____ _ CENSUS OF INDIA-1981 A-CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBUCATIONS The 1981 Census Reports on Punjab will bear uniformly Series No.